Pragmatics/History

Before 1600s 1700s 1800s 1900s 1910s 1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s |

Overview

[edit | edit source]Complementarity

[edit | edit source]

- genetic vs. acquired

- Semantic vs. pragmatic

- Certainty vs. uncertainty

- Empiricism vs. rationalism

- Explication vs. implication

- Objectivity! vs. subjectivity

- Projectivity! vs. subjectivity

- Dehumanization vs. humanization

- Full automation vs. interactivity

- Machine learning vs. human learning

Chronicle

[edit | edit source]Before

[edit | edit source]1600s

[edit | edit source]Locke

[edit | edit source]Men content themselves with the same words other people use, as if the very sound carried the same meaning.

This is included in the opening quotations of Literature/1923/Ogden.

This could be such an allusion that:

Men content themselves with the same words other people use, as if the very sound

(say, of the bible)carried the same meaning.

1700s

[edit | edit source]1800s

[edit | edit source]1900s

[edit | edit source]1903 Welby

[edit | edit source]1905 Russell

[edit | edit source]- Russell, Bertrand (1905). "On Denoting." Mind, vol. 14, pp. 479-493. [^]

1910s

[edit | edit source]1911 Welby

[edit | edit source]- Welby, Victoria Lady (1911). Significs and Language: The Articulate Form of Our Expressive and Interpretive Resources. H. Walter Schmitz, ed., John Benjamins, 1985. [^]

1916 Saussure

[edit | edit source]1920s

[edit | edit source]1921 Russell

[edit | edit source]- Russell, Bertrand (1921). The Analysis of Mind. London: George Allen & Unwin. [^]

1921 Sapir

[edit | edit source]1922 Wittgenstein

[edit | edit source]- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Frank P. Ramsey & C. K. Ogden, trans., Kegan Paul, 1922. [^]

1923 Malinowski

[edit | edit source]- Malinowski, Bronislaw (1923). "The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages." Supplement to: Ogden & Richards (1923), pp. 296-336. [^]

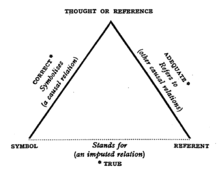

1923 Ogden and Richards

[edit | edit source]- Ogden, C. K. & I. A. Richards (1923). The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [^]

| THOUGHT relates ∧ | ||

| SYMBOL | to | REFERENT |

| or | ||

| refers SUBJECT to ∧ | ||

| PROJECT | OBJECT | |

The root of the trouble will be traced to the superstition that words are in some way parts of things or always imply things corresponding to them, historical instances of this still potent instinctive belief being given from many sources. The fundamental and most prolific fallacy is, in other words, that the base of the triangle ... is filled in. (p. 14-5)

In other words, the symbol is not the symbolized, in short, so as to be aligned with "The map is not the territory" (#1933/Korzybski) and the like.

"The influence of language upon thought" (as in the subtitle) varies from man to man, perhaps furthermore from case to case, as #Locke suggested. Then, dehumanization would be more or less unwise. No precise or wise symbolism without symbolists. Pragmatics is a must above all.

1923 Wells

[edit | edit source]- Wells, H. G. (1923). Men Like Gods. Cassell and Co., Ltd. [^]

1926 Piaget

[edit | edit source]1926 Russell

[edit | edit source]- Russell, Bertrand (1926). "The Meaning of Meaning." Dial, vol.81 (August 1926) pp. 114-121. [^]

1927 Wells

[edit | edit source]- Wells, H. G. (1927). The Way the World is Going: Guesses and Forcasts of the Years Ahead. London: Ernest Benn Ltd., 1928. [^]

1928 Wells

[edit | edit source]- Wells, H. G. (1928). The Open Conspiracy: Blue Prints For A World Revolution. Doubleday, Doran. [^]

1929 Magritte

[edit | edit source]- Magritte, René (1929). The Treachery of Images (La trahison des images). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. [^]

"This is not a pipe," as translated from the original French caption, is to say that the image is not the imaged.

1930s

[edit | edit source]1930 Empson

[edit | edit source]- Empson, William (1930). Seven Types of Ambiguity, 2nd ed., London: Chatto & Windus, 1949. [^]

1930 Frank

[edit | edit source]- Frank, Jerome (1930). Law and the Modern Mind. Peter Smith, 1930. [^]

1930 Lasswell

[edit | edit source]1930 Ogden

[edit | edit source]- Ogden, C. K. (1930). Basic English: A General Introduction with Rules and Grammar. London: Paul Treber. [^]

1933 Bloomfield

[edit | edit source]1933 Korzybski

[edit | edit source]- Korzybski, Alfred (1933). Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. 5th ed., Institute of General Semantics, 1994. [^]

The map is not the territory.

This is the dictum of Alfred Korzybski (1933) promoting general semantics. See also the map-territory relation and the like.

1933 Wells

[edit | edit source]- Wells, H. G. (1933). The Shape of Things to Come. Hutchinson. [^]

An interesting and valuable group of investigators, whose work still goes on, appeared first in a rudimentary form in the nineteenth century. The leader of this group was a certain Lady Welby (1837-1912), who was frankly considered by most of her contemporaries as an unintelligible bore. She corresponded copiously with all who would attend to her, harping perpetually on the idea that language could be made more exactly expressive, that there should be a "Science of Significs". C. K. Ogden and a fellow Fellow of Magdalene College, I. A. Richards (1893-1977), were among the few who took her seriously. These two produced a book, The Meaning of Meaning, in 1923 which counts as one of the earliest attempts to improve the language mechanism. Basic English was a by-product of these enquiries. The new Science was practically unendowed, it attracted few workers, and it was lost sight of during the decades of disaster. It was revived only in the early twenty-first century. (wiki links)

— From Language and Mental Growth

See also

[edit | edit source]- #1903 Welby What is Meaning?

- #1905 Russell On Denotation

- #1905 Wells A Modern Utopia

- #1911 Welby Significs and Language

- #1914 Wells The World Set Free

- #1923 Ogden The Meaning of Meaning

- #1923 Wells Men like Gods

- #1927 Wells The Way the World is Going

- #1928 Wells Open Conspiracy

- #1930 Ogden Basic English

- #1933 Wells The Shape of Things to Come

- #1936 Richards The Philosophy of Rhetoric

- #1938 Wells World Brain

- #1986 Rhodes The Making of the Atomic Bomb

1934 Benedict

[edit | edit source]1935 Carnap

[edit | edit source]1936 Ayer

[edit | edit source]1936 Lewin

[edit | edit source]- Lewin, Kurt (1936). Principles Of Topological Psychology. Munshi Press, 2007. [^]

1936 Richards

[edit | edit source]- Richards, I. A. (1936). The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford University Press. [^]

1937 Palmer

[edit | edit source]- Harold E. Palmer & Albert S. Hornby (1937). Thousand-word English: what it is and what can be done with it. G.G. Harrap & Company, Ltd. [^]

1938 Chase

[edit | edit source]- Chase, Stuart (1938). The Tyranny of Words. Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1938. [^]

1938 Wells

[edit | edit source]- Wells, H. G. (1938). World Brain. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co. [^]

1939 Sapir

[edit | edit source]1940s

[edit | edit source]1940 Huxley

[edit | edit source]- Huxley, Aldous (1940). Words and Their Meanings. The Ward Ritchie Press, 1940. [^]

A great deal of attention has been paid . . . to the technical languages in which men of science do their specialized thinking … But the colloquial usages of everyday speech, the literary and philosophical dialects in which men do their thinking about the problems of morals, politics, religion and psychology -- these have been strangely neglected. We talk about "mere matters of words" in a tone which implies that we regard words as things beneath the notice of a serious-minded person.

This is a most unfortunate attitude. For the fact is that words play an enormous part in our lives and are therefore deserving of the closest study. The old idea that words possess magical powers is false; but its falsity is the distortion of a very important truth. Words do have a magical effect -- but not in the way that magicians supposed, and not on the objects they were trying to influence. Words are magical in the way they affect the minds of those who use them. "A mere matter of words," we say contemptuously, forgetting that words have power to mould men's thinking, to canalize their feeling, to direct their willing and acting. Conduct and character are largely determined by the nature of the words we currently use to discuss ourselves and the world around us.

This is quoted in opening "Book One: The Functions of Language" in: Hayakawa, S. I. (1949). Language in Thought and Action. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1949. [^] See #1949 Hayakawa.

1941 Burke

[edit | edit source]1942 Langer

[edit | edit source]1943 Craik

[edit | edit source]- Craik, Kenneth (1943). The Nature of Explanation. Cambridge University Press. [^]

1944 Cassirer

[edit | edit source]1945 Bush

[edit | edit source]- Bush, Vannevar (1945). "As We May Think." The Atlantic Monthly (July 1945): 101-108. [^]

1946 Morris

[edit | edit source]1947 Northrop

[edit | edit source]- Northrop, F. S. C. (1947). The Logic of the Sciences and the Humanities. New York: Meridian Books. [^]

1948 Skinner

[edit | edit source]- Skinner, B. F. (1948). Walden Two. Macmillan Co., 1948. [^]

1948 Wiener

[edit | edit source]- Wiener, Norbert (1948). Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. 2nd ed., The MIT Press, 1965. [^]

The mechanical brain does not secrete thought "as the liver does bile," as the earlier materialists claimed, nor does it put it out in the form of energy, as the muscle puts out its activity. Information is information, not matter or energy. No materialism which does not admit this can survive at the present day.

— From Computing Machines and the Nervous System (p. 132)

As in the case of the individual, not all the information which is available to the race at one time is accessible without special effort. There is a well-known tendency of libraries to become clogged by their own volume; of the sciences to develop such a degree of specialization that the expert is often illiterate outside his own minute specialty. Dr. Vannevar Bush has suggested the use of mechanical aids for the searching through vast bodies of material. These probably have their uses, but they are limited by the impossibility of classifying a book under an unfamiliar heading unless some particular person has already recognized the relevance of that heading for that particular book. In the case where two subjects have the same technique and intellectual content but belong to widely separated fields, this still requires some individual with an almost Leibnizian catholicity of interest.

— From Information, Language, and Society (p. 158) (wiki links)

1949 Hayakawa

[edit | edit source]- Hayakawa, S. I. (1949). Language in Thought and Action. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1949. [^]

Citizens of a modern society need [...] more than that ordinary "common sense" which was defined by Stuart Chase as that which tells you that the world is flat. They need to be systematically aware of the powers and limitations of symbols, especially words, if they are to guard against being driven into complete bewilderment by the complexity of their semantic environment. The first of the principles governing symbols is this: The symbol is NOT the thing symbolized; the word is NOT the thing; the map is NOT the territory it stands for. (p.29-30) (editor's link)

— From The Word is Not the Thing

"The symbol is NOT the thing symbolized," for one. How many parodies there appear as if each varied!

Now, to use the famous metaphor by Alfred Korzybski in his Science and Sanity (1933), this verbal world ought to stand in relation to the extensional world as a map does to the territory it is supposed to represent. If a child grows to adulthood with a verbal world in his head which corresponds fairly closely to the extensional world that he finds around him in his widening experience, he is in relatively small danger of being shocked or hurt by what he finds, because his verbal world has told him what, more or less, to expect. He is prepared for life. If, however, he grows up with a false map in his head [...] he will constantly be running into trouble, wasting his efforts, and acting like a fool. He will not be adjusted to the world as it is: he may, if the lack of adjustment is serious, end up in a mental hospital. (p.31) (editor's link)

— From Maps and Territories

We all inherit a great deal of useless knowledge, and a great deal of misinformation and error (maps that were formerly thought to be accurate), so that there is always a portion of what we have been told that must be discarded. But the cultural heritage of our civilization that is transmitted to us -- our socially pooled knowledge, both scientific and humane -- has been valued principally because we have believed that it gives us accurate maps of experience. The analogy of verbal words to maps is an important one [...]. It should be noticed at this point, however, that there are two ways of getting false maps of the world into our heads: first, by having them given to us; second, by creating them ourselves when we misread the true maps given to us. (p.32)

— From Maps and Territories

See also

[edit | edit source]- #1923 Ogden

- #1929 Magritte

- #1933 Korzybski

- #1940 Huxley

- #1949 Hayakawa

- #1972 Bateson

- #1982 Berman

- q: Language in Thought and Action

1949 Orwell

[edit | edit source]- Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Secker and Warburg, 1949. [^]

1949 Ryle

[edit | edit source]- Ryle, Gilbert (1949). The Concept of Mind. University Of Chicago Press. [^]

1950s

[edit | edit source]1950 Rapoport

[edit | edit source]1950 Strawson

[edit | edit source]- Strawson, Peter (1950). "On Referring." Mind, vol. 59, no. 235, pp. 320-344. [^]

1951 Lewin

[edit | edit source]1952 Hutchins

[edit | edit source]- Hutchins, Robert, ed. (1952). Great Books of the Western World. Encyclopaedia Britannica. [^]

1953 Deutsch

[edit | edit source]1953 Wittgenstein

[edit | edit source]- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing. [^]

1954 Black

[edit | edit source]- Black, Max (1954). "Metaphor." Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 55, pp. 273-294. [^]

1954 Chase

[edit | edit source]1955 Austin

[edit | edit source]- Austin, J. L. (1955). How to Do Things with Words. The William James Lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955, ed. by J. O. Urmson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1962. [^]

1955 McCarthy

[edit | edit source]- McCarthy, John; Marvin Minsky; Nathan Rochester & Claude Shannon (1955). A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. [^]

1956 Whorf

[edit | edit source]1957 Cherry

[edit | edit source]- Cherry, Colin (1957). On Human Communication: A Review, a Survey, and a Criticism . The M.I.T. Press, 1966. [^]

The suggestion that words are symbols for things, actions, qualities, relationships, et cetera, is naive, a gross simplification. Words are slippery customers. The full meaning of a word does not appear until it is placed in its context, and the context may serve an extremely subtle function -- as with puns, or double entendre. And even then the "meaning" will depend upon the listener, upon the speaker, upon their entire experience of language, upon their knowledge of one another, and upon the whole situation. Words do not "mean things" in a one-to-one relation like a code. Words, too, are empirical signs, not copies or models of anything; truly, onomatopoeia and gestures frequently seem to possess resemblance, but this resemblance does not bear too close examination. A cockerel may seem to say cook-a-doodle-do to an Englishman, but a German thinks it says kikeriki, and a Japanese kokke-kekko. Each can paint only with the phonetic sound of his own language. (p. 10-11)

— From What Is It That We Communicate?

See also

[edit | edit source]1957 Osgood

[edit | edit source]1957 Skinner

[edit | edit source]- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Acton, Massachusetts: Copley Publishing Group. [^]

1958 Polanyi

[edit | edit source]1959 Chomsky

[edit | edit source]- Chomsky, Noam (1959). "A Review of B. F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior." Language, 35(1): 26-57. [^]

1959 Gellner

[edit | edit source]- Gellner, Ernest (1959). Words and Things: A Critical Account of Linguistic Philosophy and a Study in Ideology. London: Gollancz. [^]

1959 Snow

[edit | edit source]- Snow, Charles Percy (1959). The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (Rede Lecture). Cambridge University Press, 1959. [^]

1960s

[edit | edit source]1960 Quine

[edit | edit source]- Quine, Willard (1960). Word and Object. MIT Press. [^]

1961 Lewis

[edit | edit source]1962 Austin

[edit | edit source]1962 Black

[edit | edit source]1962 Kuhn

[edit | edit source]- Kuhn, Thomas (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press. [^]

1962 Leavis

[edit | edit source]1962 Piaget

[edit | edit source]1962 Sellars

[edit | edit source]1962 Vygotsky

[edit | edit source]1963 Popper

[edit | edit source]- Popper, Karl (1963), Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge,. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [^]

1964 Einbinder

[edit | edit source]- Einbinder, Harvey (1964). The Myth of the Britannica. New York: Grove Press. [^]

1964 McLuhan

[edit | edit source]1966 Berger

[edit | edit source]1966 Foucault

[edit | edit source]1967 Bono

[edit | edit source]1967 Koestler

[edit | edit source]1967 Miller

[edit | edit source]1967 Polanyi

[edit | edit source]1968 Piaget

[edit | edit source]1968 Roszak

[edit | edit source]1969 Blumer

[edit | edit source]1969 Nida

[edit | edit source]1970s

[edit | edit source]1972 Bateson

[edit | edit source]We say the map is different from the territory. But what is the territory? [...] Always, the process of representation will filter it out so that the mental world is only maps of maps, ad infinitum.

1973 Geertz

[edit | edit source]- Geertz, Clifford (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [^]

1974 Pirsig

[edit | edit source]- Pirsig, Robert (1974). Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values. William Morrow & Co. [^]

1975 Buzan

[edit | edit source]1975 Douglas

[edit | edit source]- Douglas, Mary (1975). Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology. Routledge. [^]

1975 Fodor

[edit | edit source]- Fodor, Jerry (1975). The Language of Thought. Harvard University Press. [^]

1975 Grice

[edit | edit source]- Grice, Paul (1975). "Logic and Conversation," pp. 41-58, in: Cole, Peter & Jerry L. Morgan eds. (1975). Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Act. New York: Academic Press. [^]

1975 Kochen

[edit | edit source]- Kochen, Manfred, ed. (1975). Information for Action: from Knowledge to Wisdom. New York: Academic Press. [^]

1975 Krishnamurti

[edit | edit source]The description is not the described.

Jiddu Krishnamurti (c. 1975) [1] explained: "it is like a man who is hungry. Any amount of description of the right kind of food will never satisfy him. He is hungry, he wants food."

1975 Pask

[edit | edit source]- Pask, Gordon (1975). Conversation, Cognition and Learning. Elsevier. [^]

Conversation theory is a cybernetic and dialectic framework that offers a scientific theory to explain how interactions lead to "construction of knowledge", or, "knowing": wishing to preserve ... the necessity for there to be a "knower".[2] This work is proposed by Gordon Pask in the 1970s.

Conversation theory regards social systems as symbolic, language-oriented systems where responses depend on one person's interpretation of another person's behavior, and where meanings are agreed through conversations. But since meanings are agreed, and the agreements can be illusory and transient, scientific research requires stable reference points in human transactions to allow for reproducible results. Pask found these points to be the understandings which arise in the conversations between two participating individuals, and which he defined rigorously.

Conversation theory describes interaction between two or more cognitive systems, such as a teacher and a student or distinct perspectives within one individual, and how they engage in a dialog over a given concept and identify differences in how they understand it.

Conversation theory came out of the work of Gordon Pask on instructional design and models of individual learning styles. In regard to learning styles, he identified conditions required for concept sharing and described the learning styles holist, serialist, and their optimal mixture versatile. He proposed a rigorous model of analogy relations.— From w: Conversation Theory

See also

[edit | edit source]- #1978 Dunn as to "learning style"

1975 Percy

[edit | edit source]- Percy, Walker (1975). The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [^]

The Delta Factor, Percy's theory of language, is framed in the context of the story of Helen Keller's learning to say and sign the word water while Annie Sullivan poured water over her hands and repeatedly made the signs for the word into her hand. A behaviorist linguistic reading of this scene might suggest a causal relationship -- in other words, Keller felt Sullivan's sign-language stimulus in her hand and in response made a connection in her brain between the signifier and the signified. This is too simplistic a reading, says Percy, because Keller was receiving from both the signifier (the sign for water) and the referent (the water itself). This creates a triangle between water (the word), water (the liquid), and Helen, in which all three corners lead to the other two corners and which Percy says is "absolutely irreducible". This linguistic triangle is thus the building block for all of human intelligence. The moment when this Delta Δ entered the mind of man -- whether this happened via random chance or through the intervention of a deity -- he became man.

— From w: The Message in the Bottle

1975 Polanyi

[edit | edit source]- Polanyi, Michael & Harry Prosch (1975). Meaning. University of Chicago Press. [^]

Published very shortly before his death in February 1976, Meaning is the culmination of Michael Polanyi's philosophic endeavors. With the assistance of Harry Prosch, Polanyi goes beyond his earlier critique of scientific "objectivity" to investigate meaning as founded upon the imaginative and creative faculties.

Establishing that science is an inherently normative form of knowledge and that society gives meaning to science instead of being given the "truth" by science, Polanyi contends here that the foundation of meaning is the creative imagination. Largely through metaphorical expression in poetry, art, myth, and religion, the imagination is used to synthesize the otherwise chaotic and disparate elements of life. To Polanyi these integrations stand with those of science as equally valid modes of knowledge. He hopes this view of the foundation of meaning will restore validity to the traditional ideals that were undercut by modern science. Polanyi also outlines the general conditions of a free society that encourage varied approaches to truth, and includes an illuminating discussion of how to restore, to modern minds, the possibility for the acceptance of religion.— From the back matter

1975 Putnam

[edit | edit source]- Putnam, Hilary (1975). Mind, Language and Reality, Philosophical Papers Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press. [^]

One of Putnam's contributions to philosophy of language is his claim that "meanings just ain't in the head". He illustrated this using his "Twin Earth" thought experiment to argue that environmental factors play a substantial role in determining meaning. Twin Earth shows this, according to Putnam, since on Twin Earth everything is identical to Earth, except that its lakes, rivers and oceans are filled with XYZ whereas those of earth are filled with H2O. Consequently, when an earthling, Fredrick, uses the Earth-English word "water", it has a different meaning from the Twin Earth-English word "water" when used by his physically identical twin, Frodrick, on Twin Earth. Since Fredrick and Frodrick are physically indistinguishable when they utter their respective words, and since their words have different meanings, meaning cannot be determined solely by what is in their heads. This led Putnam to adopt a version of semantic externalism with regard to meaning and mental content.[3] [4] The late philosopher of mind and language Donald Davidson, despite his many differences of opinion with Putnam, wrote that semantic externalism constituted an "anti-subjectivist revolution" in philosophers' way of seeing the world. Since the time of Descartes, philosophers had been concerned with proving knowledge from the basis of subjective experience. Thanks to Putnam, Tyler Burge and others, Davidson said, philosophy could now take the objective realm for granted and start questioning the alleged "truths" of subjective experience.[5]

Putnam's "anti-subjectivist revolution" is diametrically contrasted with the humanist or anti-objectivist revolution, as suddenly getting torrent since the 1973 oil crisis, as illustrated by #1974 Pirsig, #1975 Grice, #1975 Percy, #1975 Polanyi, and many others. He looks not so much revolutionary as reactionary.

1975 Ricoeur

[edit | edit source]- Ricoeur, Paul (1975). The Rule of Metaphor: Multi-Disciplinary Studies in the Creation of Meaning in Language. Robert Czerny, Kathleen McLaughlin & John Costello, trans., London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978. [^]

1976 Boyd

[edit | edit source]- Boyd, John (1976). Destruction and Creation. Goal Systems International. [^]

To comprehend and cope with our environment we develop mental patterns or concepts of meaning. The purpose of this paper is to sketch out how we destroy and create these patterns to permit us to both shape and be shaped by a changing environment. In this sense, the discussion also literally shows why we cannot avoid this kind of activity if we intend to survive on our own terms.

The activity is dialectic in nature generating both disorder and order that emerges as a changing and expanding universe of mental concepts matched to a changing and expanding universe of observed reality.— Abstract

1976 Chisholm

[edit | edit source]- Chisholm, Roderick (1976). Person and Object: A Metaphysical Study. London: G. Allen & Unwin. [^]

Suggesting pragmatics, the title is deliberately contrasted with Quine, Willard (1960). Word and Object. MIT Press. [^]

1976 Leach

[edit | edit source]- Leach, Edmund (1976). Culture and Communication: The Logic by Which Symbols are Connected. Cambridge University Press. [^]

1977 Gibson

[edit | edit source]- Gibson, Jame J. (1977). "The Theory of Affordances," pp. 67-82. In: Robert Shaw & John Bransford, eds. Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [^]

1978 Dunn

[edit | edit source]1978 Sacks

[edit | edit source]- Sacks, Sheldon, ed. (1978). Critical Inquiry, vol. 5, no. 1 (Special Issue: On Metaphor), University of Chicago. [^]

1978 Turner

[edit | edit source]- Turner, Victor & Edith Turner (1978). Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives. Columbia University Press. [^]

1979 Gibson

[edit | edit source]- Gibson, Jame J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [^]

1979 Lyotard

[edit | edit source]- Lyotard, Jean-François (1979). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. [^]

1979 Ortony

[edit | edit source]1979 Rorty

[edit | edit source]- Rorty, Richard (1979). Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton University Press. [^]

1980s

[edit | edit source]1980 Bohm

[edit | edit source]- David Bohm (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge. [^]

1980 Fish

[edit | edit source]- Fish, Stanley (1980). Is There A Text in This Class?: The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Harvard University Press. [^]

1980 Lakoff and Johnson

[edit | edit source]- Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press. [^]

1982 Berman

[edit | edit source]- Berman, Sanford (1982). Words, Meanings and People, International Society for General Semantics,Concord, CA, 2001. [^]

Many scholars have long recognized this semantic problem. One of the earliest and greatest semanticists was A. B. Johnson. He said, "Much of what is esteemed as profound philosophy is nothing but a disputatious criticism on the meaning of words." Professor A. Schuster said, "Scientific controversies constantly resolve themselves into differences about the meaning of words." And John Locke observed, "Men content themselves with the same words as other people use, as if the sound necessarily carried the same meaning."

Compare the three quotes respectively with:

- Literature/1923/Ogden/Opening quotations#Hume

- Literature/1923/Ogden/Opening quotations#Schuster

- Literature/1923/Ogden/Opening quotations#Locke

Language is an important variable in thinking, perceiving, communicating and behaving. This is one of the important principles in general semantics. The title of Korzybski's above article[6] implies the relationship between language and human perception. Anthropologists and linguists such as Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, along with Korzybski, have emphasized the important role that language plays in thinking, perceiving and behaving. (p. 44-45)

— From Our human limitations

Cf. The subtitle of Ogden, C. K. & I. A. Richards (1923). The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [^]

1982 Eco

[edit | edit source]- 1:1 map

1984 Blackburn

[edit | edit source]1986 Rhodes

[edit | edit source]In London, where Southampton Row passes Russell Square, across from the British Museum in Bloomsbury, Leo Szilard waited irritably one gray depression morning for the stoplight to change. A trace of rain had fallen during the night; Tuesday, September 12, 1933, dawned cool, humid and dull. Drizzling rain would begin again in early afternoon. When Szilard told the story later he never mentioned his destination that morning. He may have had none; he often walked to think. In any case another destination intervened. The stoplight changed to green. Szilard stepped off the curb. As he crossed the street time cracked open before him and he saw a way to the future, death into the world and all our woes, the shape of things to come. (wiki links)

1987 Kochen

[edit | edit source]- Kochen, Manfred (1987). "How Well Do We Acknowledge Intellectual Debts?" Journal of Documentation, 43 (1): 54-64. [^]

1989 Kochen

[edit | edit source]- Kochen, Manfred, ed. (1989). The Small World: A Volume of Recent Research Advances Commemorating Ithiel de Sola Pool, Stanley Milgram, Theodore Newcomb. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp. (January 1, 1989). [^]

1989 Rorty

[edit | edit source]The contingency of language

Here, Rorty argues that all language is contingent. This is because only descriptions of the world can be true or false, and descriptions are made by humans who must make truth or falsity, as opposed to truth or falsity being determined by any innate property of the world being described. Green grass is not true or false, but "the grass is green" is. For example, I can say that 'the grass is green' and you could agree with that statement (which for Rorty makes the statement true), but our use of the words to describe grass is independent of the grass itself. Without the human proposition, truth or falsity is simply irrelevant. Rorty consequently argues that all discussion of language in relation to reality should be abandoned, and that one should instead discuss vocabularies in relation to other vocabularies.

See also

[edit | edit source]1990s

[edit | edit source]1990 Bruner

[edit | edit source]- Bruner, Jerome (1990). Acts of Meaning (The Jerusalem-Harvard Lectures). Harvard University Press. [^]

I want to begin with the Cognitive Revolution as my point of departure. That revolution was intended to bring "mind" back into the human sciences after a long cold winter of objectivism. (wiki links)

— From The Proper Study of Man

1990 Blackburn

[edit | edit source]Thoughts are strange things. They have 'representational' powers: a thought typically represents the world as being one way or another. A sensation, by contrast, seems to just sit there. (p. 78)

— From Mind

A signpost doesn't in and of itself represent the way to the village. We have to learn how to take it. (p. 78)

— From Mind

1994 Popper

[edit | edit source]Why do I think that we, the intellectuals, are able to help? Simply because we, the intellectuals, have done the most terrible harm for thousands of years. Mass murder in the name of an idea, a doctrine, a theory, a religion -- that is all our doing, our invention: the invention of the intellectuals. If only we would stop setting man against man -- often with the best intentions -- much would be gained. Nobody can say that it is impossible for us to stop doing this.

See also

[edit | edit source]2000s

[edit | edit source]2001 Gaiman

[edit | edit source]- Literature/2001/Gaiman [^] -- Neil Gaiman (2001) Fragile Things

The more accurate the map, the more it resembles the territory. The most accurate map possible would be the territory, and thus would be perfectly accurate and perfectly useless.

2010s

[edit | edit source]Case History

[edit | edit source]E. O. Wilson, a biologist and entomology professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University wrote that "the political objections forcefully made by the Sociobiology Study Group of Science for the People in particular took me by surprise." Wilson stated:

I had been blindsided by the attack. Having expected some frontal fire from social scientists on primarily evidential grounds, I had received instead a political enfilade from the flank. A few observers were surprised that I was surprised. John Maynard Smith, a senior British evolutionary biologist and former Marxist, said that he disliked the last chapter of Sociobiology himself and "it was also absolutely obvious to me--I cannot believe Wilson didn't know--that this was going to provoke great hostility from American Marxists, and Marxists everywhere." But it was true that I didn't know. I was unprepared perhaps because, as Maynard Smith further observed, I am an American rather than a European. In 1975 I was a political naive: I knew almost nothing about Marxism as either a political belief or a mode of analysis; I had paid little attention to the dynamism of the activist Left, and I had never heard of Science for the People. I was not an intellectual in the European or New York/Cambridge sense. ... After the Sociobiology Study Group exposed me as a counterrevolutionary adventurist, and as they intensified their attacks in articles and teach-ins, other radical activists in the Boston area, including the violence-prone International Committee against Racism, conducted a campaign of leaflets and teach-ins of their own to oppose human sociobiology. As this activity spread through the winter and spring of 1975-76, I grew fearful that it might reach a level embarrassing to my family and the university. I briefly considered offers of professorships from three universities--in case, their representatives said, I wished to leave the physical center of the controversy. But the pressure was tolerable, since I was a senior professor with tenure, with a reputation based on other discoveries, and in any case could not bear to leave Harvard's ant collection, the world's largest and best. For a few days a protester in Harvard Square used a bullhorn to call for my dismissal. Two students from the University of Michigan invaded my class on evolutionary biology one day to shout slogans and deliver antisociobiology monologues. I withdrew from department meetings for a year to avoid embarrassment arising from my notoriety, especially with key members of Science for the People present at these meetings. In 1979 I was doused with water by a group of protestors at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, possibly the only incident in recent history that a scientist was physically attacked, however mildly, for the expression of an idea. In 1982 I went to the Science Center at Harvard University under police escort to deliver a public lecture, because of the gathering of a crowd of protestors around the entrance, angered because of the title of my talk: "The coevolution of biology and culture."

- See also

References

[edit | edit source]- Pavlov, Ivan (1903). "The Experimental Psychology and Psychopathology of Animals." The 14th International Medical Congress, Madrid, Spain, April 23-30, 1903. [^]

- Literature/1903/Welby [^]

- Russell, Bertrand (1905). "On Denoting." Mind, vol. 14, pp. 479-493. [^]

- Wells, H. G. (1905). A Modern Utopia. New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2005. [^]

- Welby, Victoria Lady (1911). Significs and Language: The Articulate Form of Our Expressive and Interpretive Resources. H. Walter Schmitz, ed., John Benjamins, 1985. [^]

- Watson, John B. (1913). "Psychology as the behaviorist views it," Psychological Review, 20, pp. 158-177. [^]

- Literature/1916/Saussure [^]

- Russell, Bertrand (1921). The Analysis of Mind. London: George Allen & Unwin. [^]

- Literature/1921/Sapir [^]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Frank P. Ramsey & C. K. Ogden, trans., Kegan Paul, 1922. [^]

- Malinowski, Bronislaw (1923). "The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages." Supplement to: Ogden & Richards (1923), pp. 296-336. [^]

- Ogden, C. K. & I. A. Richards (1923). The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [^]

- Wells, H. G. (1923). Men Like Gods. Cassell and Co., Ltd. [^]

- Literature/1926/Piaget [^]

- Russell, Bertrand (1926). "The Meaning of Meaning." Dial, vol.81 (August 1926) pp. 114-121. [^]

- Magritte, René (1929). The Treachery of Images (La trahison des images). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. [^]

- Frank, Jerome (1930). Law and the Modern Mind. Peter Smith, 1930. [^]

- Empson, William (1930). Seven Types of Ambiguity, 2nd ed., London: Chatto & Windus, 1949. [^]

- Literature/1930/Lasswell [^]

- Ogden, C. K. (1930). Basic English: A General Introduction with Rules and Grammar. London: Paul Treber. [^]

- Russell, Bertrand (1931). The Scientific Outlook. London: George Allen & Unwin. [^]

- Huxley, Aldous (1932). Brave New World. Harper Perennial, 1932. [^]

- Literature/1933/Bloomfield [^]

- Korzybski, Alfred (1933). Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. 5th ed., Institute of General Semantics, 1994. [^]

- Wells, H. G. (1933). The Shape of Things to Come. Hutchinson. [^]

- Literature/1934/Benedict [^]

- Literature/1934/Mead [^]

- Literature/1935/Carnap [^]

- Literature/1936/Ayer [^]

- Lewin, Kurt (1936). Principles Of Topological Psychology. Munshi Press, 2007. [^]

- Richards, I. A. (1936). The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford University Press. [^]

- Harold E. Palmer & Albert S. Hornby (1937). Thousand-word English: what it is and what can be done with it. G.G. Harrap & Company, Ltd. [^]

- Chase, Stuart (1938). The Tyranny of Words. Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1938. [^]

- Wells, H. G. (1938). World Brain. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co. [^]

- Literature/1939/Sapir [^]

- Huxley, Aldous (1940). Words and Their Meanings. The Ward Ritchie Press, 1940. [^]

- Literature/1941/Burke [^]

- Literature/1942/Huxley [^]

- Literature/1942/Langer [^]

- Craik, Kenneth (1943). The Nature of Explanation. Cambridge University Press. [^]

- Literature/1944/Cassirer [^]

- Bush, Vannevar (1945). "As We May Think." The Atlantic Monthly (July 1945): 101-108. [^]

- Literature/1946/Morris [^]

- Carnap, Rudolf (1947). Meaning and Necessity: A Study in Semantics and Modal Logic. University of Chicago Press. [^]

- Northrop, F. S. C. (1947). The Logic of the Sciences and the Humanities. New York: Meridian Books. [^]

- Skinner, B. F. (1948). Walden Two. Macmillan Co., 1948. [^]

- Wiener, Norbert (1948). Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. 2nd ed., The MIT Press, 1965. [^]

- Hayakawa, S. I. (1949). Language in Thought and Action. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1949. [^]

- Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Secker and Warburg, 1949. [^]

- Ryle, Gilbert (1949). The Concept of Mind. University Of Chicago Press. [^]

- Literature/1950/Rapoport [^]

- Strawson, Peter (1950). "On Referring." Mind, vol. 59, no. 235, pp. 320-344. [^]

- Wiener, Norbert (1950). The Human Use of Human Beings. 2nd ed., Houghton Milfflin, 1954. [^]

- Literature/1951/Lewin [^]

- Hutchins, Robert, ed. (1952). Great Books of the Western World. Encyclopaedia Britannica. [^]

- Literature/1953/Deutsch [^]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing. [^]

- Black, Max (1954). "Metaphor." Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 55, pp. 273-294. [^]

- Literature/1954/Chase [^]

- Austin, J. L. (1955). How to Do Things with Words. The William James Lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955, ed. by J. O. Urmson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1962. [^]

- McCarthy, John; Marvin Minsky; Nathan Rochester & Claude Shannon (1955). A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. [^]

- Literature/1956/Whorf [^]

- Cherry, Colin (1957). On Human Communication: A Review, a Survey, and a Criticism . The M.I.T. Press, 1966. [^]

- Literature/1957/Osgood [^]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Acton, Massachusetts: Copley Publishing Group. [^]

- Literature/1958/Polanyi [^]

- Chomsky, Noam (1959). "A Review of B. F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior." Language, 35(1): 26-57. [^]

- Gellner, Ernest (1959). Words and Things: A Critical Account of Linguistic Philosophy and a Study in Ideology. London: Gollancz. [^]

- Snow, Charles Percy (1959). The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (Rede Lecture). Cambridge University Press, 1959. [^]

- Literature/1960/Lewis [^]

- Quine, Willard (1960). Word and Object. MIT Press. [^]

- Literature/1961/Booth [^]

- Literature/1961/Lewis [^]

- Literature/1962/Austin [^]

- Literature/1962/Black [^]

- Kuhn, Thomas (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press. [^]

- Literature/1962/Leavis [^]

- Literature/1962/Piaget [^]

- Literature/1962/Sellars [^]

- Literature/1962/Vygotsky [^]

- Popper, Karl (1963), Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge,. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [^]

- Einbinder, Harvey (1964). The Myth of the Britannica. New York: Grove Press. [^]

- Literature/1964/McLuhan [^]

- Licklider, J. C. R. (1965). Libraries of the Future. MIT Press. [^]

- Price, Derek J. de Solla (1965). "Networks of Scientific Papers." Science 149 (3683): 510-515. [^]

- Literature/1966/Berger [^]

- Literature/1966/Foucault [^]

- Literature/1967/Bono [^]

- Literature/1967/Koestler [^]

- Literature/1967/Miller [^]

- Literature/1967/Polanyi [^]

- Literature/1968/Piaget [^]

- Literature/1968/Roszak [^]

- Literature/1969/Blumer [^]

- Kochen, Manfred (1969). "Stability in the Growth of Knowledge." American Documentation, 20 (3): 186-197. [^]

- Literature/1969/Nida [^]

- Literature/1972/Bateson [^]

- Geertz, Clifford (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [^]

- Pirsig, Robert (1974). Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values. William Morrow & Co. [^]

- Werner Abraham (1975). A Linguistic Approach to Metaphor. Lisse, Netherlands: Peter de Ridder Press. [^]

- This book is written by Thomas Jefferson [^]

- Literature/1975/Capra [^]

- Cole, Peter & Jerry L. Morgan, eds. (1975). Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Act. New York: Academic Press. [^]

- Collins, Allan M. & Elizabeth F. Loftus (1975). "A Spreading-Activation Theory of Semantic Processing." Psychological Review (November 1975) 82 (6): 407-428. [^]

- Literature/1975/Culler [^]

- Douglas, Mary (1975). Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology. Routledge. [^]

- Feyerabend, Paul (1975). Against Method: Outline of an Anarchist Theory of Knowledge. New Left Books. [^]

- Fodor, Jerry (1975). The Language of Thought. Harvard University Press. [^]

- Literature/1975/Gadamer [^]

- Grice, Paul (1975). "Logic and Conversation," pp. 41-58, in: Cole, Peter & Jerry L. Morgan eds. (1975). Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Act. New York: Academic Press. [^]

- Hacking, Ian (1975). Why Does Language Matter to Philosophy? Cambridge University Press. [^]

- Kochen, Manfred, ed. (1975). Information for Action: from Knowledge to Wisdom. New York: Academic Press. [^]

- Literature/1975/Kolb [^]

- Literature/1975/Lasswell [^]

- Leavis, Frank (1975). The Living Principle: 'English' as a Discipline of Thought. London: Chatto & Windus. [^]

- Literature/1975/Lewis [^]

- Literature/1975/Luckmann [^]

- Literature/1975/MacKay [^]

- Minsky, Marvin (1975). "A Framework for Representing Knowledge," in: Winston, Patrick, ed. (1975). The Psychology of Computer Vision. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 211-77. [^]

- Literature/1975/Norman [^]

- Pask, Gordon (1975). Conversation, Cognition and Learning. Elsevier. [^]

- Percy, Walker (1975). The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [^]

- Literature/1975/Pfeiffer [^]

- Literature/1975/Piattelli-Palmarini [^]

- Literature/1975/Pocock [^]

- Polanyi, Michael & Harry Prosch (1975). Meaning. University of Chicago Press. [^]

- Putnam, Hilary (1975). Mind, Language and Reality, Philosophical Papers Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press. [^]

- Ricoeur, Paul (1975). The Rule of Metaphor: Multi-Disciplinary Studies in the Creation of Meaning in Language. Robert Czerny, Kathleen McLaughlin & John Costello, trans., London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978. [^]

- Schank, Roger C. (1975). "The Structure of Episodes in Memory," in: Literature/1975/Bobrow pp. 237-272. [^]

- Searle, John (1975). "Indirect Speech Acts," pp. 59-82, in: Cole, Peter & Jerry L. Morgan, eds. (1975). Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Act. New York: Academic Press. [^]

- Sperber, Dan (1975). Rethinking Symbolism. Cambridge University Press. [^]

- Boyd, John (1976). Destruction and Creation. Goal Systems International. [^]

- Chisholm, Roderick (1976). Person and Object: A Metaphysical Study. London: G. Allen & Unwin. [^]

- Leach, Edmund (1976). Culture and Communication: The Logic by Which Symbols are Connected. Cambridge University Press. [^]

- Literature/1976/Neissser [^]

- Literature/1977/Feldenkrais [^]

- Gibson, Jame J. (1977). "The Theory of Affordances," pp. 67-82. In: Robert Shaw & John Bransford, eds. Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [^]

- Magee, Bryan (1978). Men of Ideas: Some Creators of Contemporary Philosophy. BBC Books. [^]

- Pool, Ithiel de Sola & Manfred Kochen (1978). "Contacts and Influence." Social Networks, 1, pp. 1-51. [^]

- Sacks, Sheldon, ed. (1978). Critical Inquiry, vol. 5, no. 1 (Special Issue: On Metaphor), University of Chicago. [^]

- Literature/1878/Turner [^]

- Gibson, Jame J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [^]

- Literature/1979/Bateson [^]

- Lyotard, Jean-François (1979). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. [^]

- Ortony, Andrew, ed. (1979). Metaphor and Thought, Cambridge University Press. 2nd. ed. 1993. [^]

- Rorty, Richard (1979). Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton University Press. [^]

- David Bohm (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge. [^]

- Fish, Stanley (1980). Is There A Text in This Class?: The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Harvard University Press. [^]

- Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press. [^]

- Cleveland, Harlan (1982). "Information as Resource." The Futurist, 16: 34-39. [^]

- Anderson, Benedict (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. [^]

- Eco, Umberto (1983). The Name of the Rose. Harcourt. [^]

- Gentner, Dedre & Albert L. Stevens, eds. (1983). Mental Models. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-89859-242-9. [^]

- Philip N. Johnson-Laird (1983). Mental Models: Toward a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference and Consciousness. Harvard University Press. [^]

- Shneiderman, Ben (1983). "Direct Manipulation: A Step Beyond Programming Languages," Computer, Vol. 16, No. 8 (August 1983) pp. 57-69. [^]

- Literature/1984/Blackburn [^]

- Cleveland, Harlan (1985). The Knowledge Executive: Leadership in an Information Society. New York: Truman Tally Books. [^]

- McClelland, James; David Rumelhart, and PDP Research Group (1986). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Volume 2: Psychological and Biological Models. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [^]

- Swanson, Don R. (1986). "Fish oil, Raynaud's Syndrome, and Undiscovered Public Knowledge." Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 30 (1): 7-18. [^]

- Bloom, Allan (1987). The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today's Students. New York: Simon & Schuster. [^]

- Kochen, Manfred (1987). "How Well Do We Acknowledge Intellectual Debts?" Journal of Documentation, 43 (1): 54-64. [^]

- Adler, Mortimer J. & Geraldine van Doren (1988). Reforming Education: The Opening of the American Mind. New York: Macmillan. [^]

- Eco, Umberto (1989). Foucault's Pendulum. Secker & Warburg. [^]

- Kochen, Manfred, ed. (1989). The Small World: A Volume of Recent Research Advances Commemorating Ithiel de Sola Pool, Stanley Milgram, Theodore Newcomb. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp. (January 1, 1989). [^]

- Bruner, Jerome (1990). Acts of Meaning (The Jerusalem-Harvard Lectures). Harvard University Press. [^]

- Buckland, Michael (1991). "Information as Thing." Journal of the American Society for Information Science 42 (5): 351-360. [^]

- Buckland, Michael (1992). "Emanuel Goldberg, Electronic Document Retrieval, and Vannevar Bush's Memex." Journal of the American Society for Information Science, vol. 43, no. 4 (May 1992), pp. 284-294. [^]

Footnotes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Quotes of JK from the JK Foundation http://www.jiddu-krishnamurti.net/en/jiddu-krishnamurti-quotes

- ↑ Pask, Gordon (1975). Conversation, Cognition and Learning. Elsevier. [^]

- ↑ Putnam, H. (1981): "Brains in a vat" in Reason, Truth, and History, Cambridge University Press; reprinted in DeRose and Warfield, editors (1999): Skepticism: A Contemporary Reader, Oxford UP.

- ↑ Putnam, H. (1975) Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 88-459-0257-9

- ↑ Davidson, D. (2001) Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 88-7078-832-6

- ↑ "The Role of Language in the Perceptual Process"