Philosophy/Sciences

A systematically organized body of knowledge on a particular subject is often thought of as a science. The collection of such bodies of knowledge also systematically organized likely constitutes the sciences.

A more archaic meaning is knowledge of any kind whether found through the use of the scientific method or not.

Perhaps nothing symbolizes the sciences more than astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot, walking on the surface of the Moon near the leg of the Lunar Module (LM) "Eagle" during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity (EVA). Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, took this photograph with a 70 mm lunar surface camera. While astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin descended in the Lunar Module (LM) "Eagle" to explore the Sea of Tranquility region of the Moon, astronaut Michael Collins, command module pilot, remained with the Command and Service Modules (CSM) "Columbia" in lunar orbit.

The objective of this lecture is to introduce students and others to the sciences. By the end of this lecture, the student or learner will have an introductory understanding of sciences.

This lecture offers a collaborative environment for the creation, sharing, and discussion of open educational resources, open research and open academia regarding the sciences. This lecture welcomes learners of all ages. This lecture does not grant any degrees. This lecture strives to be a learning project corresponding to all sciences at accredited educational institutions and any other topics that are of interest to Wikiversity community members. Providing for learning communities to develop, modify and use the materials on Wikiversity, itself constitutes a way in which research included here by the presence of hypotheses could be done as an activity on Wikiversity. This lecture is dynamic and continues to improve.

The sciences

[edit | edit source]

Def. the disciplines or branches of learning, especially those dealing with measurable or systematic principles, the collective disciplines of study or learning acquired through the scientific method are called the sciences.

Def. in the definite, a method of discovering knowledge about the natural world based in making falsifiable predictions (hypotheses), testing them empirically, & developing theories that match known data from repeatable physical experimentation is called the scientific method.

As an introduction to science, the Scale of the Universe is mapped to the Branches of Science. The Scale of the Universe captures the average diameter of key systems. The scale needs to be cubed to make volume; it takes about 60 trillion atoms to make a human cell, 100 trillion cells to make a person, and 108 billion people have lived to build modern society.

Branches of Science captures the major areas of study in science. The images capture the building block for the scientific branch. Math is built up from binary logic, physics is built on atomic scale physical laws, life science is built by cellular behavior calculated through natural selection, social science is built on the human brain, and earth and space science begins with our own planetary body.

Mathematics is groups of logical units, chemistry is groups of atoms following physical laws, functional biology is groups of cells functioning as organisms and ecosystems, and sociology is groups of people governed by their individual psychology.

The sciences are introduced in alphabetical order after a humanities description of the sciences.

Human conditions

[edit | edit source]It has been argued that the ultimate purpose of science is to make sense of human beings and our nature- for example in his book Consilience, EO Wilson said "The human condition is the most important frontier of the natural sciences."[1] Jeremy Griffith supports this view.[2]

Anthropology

[edit | edit source]"Some 540,000 years ago, an ancient ancestor of modern humans took a shark tooth and carefully carved a geometric engraving [shown close-up in the image on the right] on a mollusk shell."[3]

"The engraving -- the oldest piece of art ever found by at least 300,000 years -- as well as a shell tool were found at a site in what is now Java, Indonesia."[3]

The discovery was made while "studying a fossil freshwater mussel shell assemblage from a site called Trinil in Java. The mussel shells originally were excavated by Eugène Dubois in the 1890s, but have been stored in the Dubois collection of the Naturalis museum in Leiden, The Netherlands. Sediment within the shells enabled them to be dated using both isotopic and luminescence methods."[3]

Archaeology

[edit | edit source]

Archaeology studies human cultures through the recovery, documentation and analysis of material remains and environmental data, including architecture, artifacts, ecofacts, human remains, and landscapes.

Because archaeology employs a wide range of different procedures, it can be considered to be both a science and a humanity,[4]

Archaeology studies human history from the development of the first stone tools in eastern Africa 3.4 million years ago up until recent decades.[5] (Archaeology does not include the discipline of paleontology.) It is of most importance for learning about prehistoric societies, when there are no written records for historians to study, making up over 99% of total human history, from the Palaeolithic until the advent of literacy in any given society.[4]

Architecture

[edit | edit source]

Def. the art and science of designing and managing the construction of buildings and other structures, particularly if they are well proportioned and decorated"[6] is called architecture.

Astronomy

[edit | edit source]

A nomy (Latin nomia) is a "system of laws governing or [the] sum of knowledge regarding a (specified) field."[7] Nomology is the "science of physical and logical laws."[7] When any effort to acquire a system of laws or knowledge focusing on an astr, aster, or astro, that is, any natural body in the sky especially at night,[7] succeeds even in its smallest measurement, astronomy is the name of the effort and the result.

Atmospheric sciences

[edit | edit source]

Atmospheric sciences concerns the study of the Earth's atmosphere, its processes, the effects other systems have on the atmosphere, and the effects of the atmosphere on these other systems. It also focuses on the atmospheres of astronomical objects.

Def. the gases surrounding any astronomical body are called an atmosphere.

Def. the study of the atmosphere and its phenomena, especially with weather and weather forecasting is called meteorology.

Def. precipitation products of the condensation of atmospheric water vapour are called hydrometeors.

"Condensation or sublimation of atmospheric water vapor produces a hydrometeor. It forms in the free atmosphere, or at the earth's surface, and includes frozen water lifted by the wind. Hydrometeors which can cause a surface visibility reduction, generally fall into one of the following two categories:

- Precipitation. Precipitation includes all forms of water particles, both liquid and solid, which fall from the atmosphere and reach the ground; these include: liquid precipitation (drizzle and rain), freezing precipitation (freezing drizzle and freezing rain), and solid (frozen) precipitation (ice pellets, hail, snow, snow pellets, snow grains, and ice crystals).

- Suspended (Liquid or Solid) Water Particles. Liquid or solid water particles that form and remain suspended in the air (damp haze, cloud, fog, ice fog, and mist), as well as liquid or solid water particles that are lifted by the wind from the earth’s surface (drifting snow, blowing snow, blowing spray) cause restrictions to visibility. One of the more unusual causes of reduced visibility due to suspended water/ice particles is whiteout, while the most common cause is fog."[8]

Biology

[edit | edit source]Def. a status given to any entity, having the properties of replication and metabolism is called life.

Def. the study of all life or living matter including the structure, function, and behavior of an organism or type of organism is called biology.

Botany is the study of plants, including their physiology, structure, genetics, ecology, distribution, classification, and economic importance.

Def. that part of biology which relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct is called zoology.

Chemistry

[edit | edit source]

Def. a natural science that deals with the composition and constitution of substances and the changes that they undergo as a consequence of alterations in the constitution of their molecules is called chemistry.

Def. a science that deals with

- the identification of the substances of which matter is composed,

- the investigation of their properties and the ways in which they interact, combine, and change, and

- the use of these processes to form new substances

is called chemistry.

Def. "a science that deals with the composition, structure, and properties of substances and of the transformations that they undergo"[7] is called chemistry.

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties.[9][10]

Earth sciences

[edit | edit source]

Earth science is an all-embracing term for the sciences related to the planet Earth.[11]

Def. the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study through observation and experiment of the Earth's physical structure and substance, its history and origin, and the processes that act on it, especially by examination of its rocks, is called geology.

The Earth is a rocky object whose surface is mostly covered with water that is in orbit around a star called the Sun.

Geography

[edit | edit source]

Geography is the science and art of locating people and features of interest on the Earth.

Geology

[edit | edit source]

At its earliest, geology is the study of the rocks that compose the astronomical rocky object referred to as the Earth.

Logic

[edit | edit source]

Logic is more than reasoning. Usually it is reasoning conducted or assessed according to strict principles of validity.

Aristotelian logic is a particular system or codification of the principles of proof and inference.

At a secondary level an introduction to logic may be helpful, where some of the more common operators are described. This introduction is a part of elementary logic at the undergraduate level. Here, there is at least one lesson available.

This learning resource is partly an article, in some subareas an essay, and mostly a lecture.

Logic is often considered a part of philosophy. And, most often is used in science to help create knowledge consisting of facts and truths. But, it finds needed applicability in law and the practice of law. A third popular field that confers a rigid structure on logic is mathematics.

Nearly all efforts, intellectual or otherwise, can be approached and have some understanding produced through the application of logic. This includes volition (e.g., emotion), affections, morality, and religion.

Materials sciences

[edit | edit source]

Materials science is an interdisciplinary field applying the properties of matter to various areas of science and engineering.

Def. an understanding of the nature of substances whose properties make them useful in structures, machines, devices, or products, leading to theories or descriptions that explain how structure relates to composition, properties, and behavior is called materials science.

Mathematics

[edit | edit source]

Mathematics is about numbers (counting), quantity, and coordinates.

Natural sciences

[edit | edit source]"The natural sciences are those branches of science that seek to elucidate the rules that govern the natural world through scientific methods.[12]

"Fundamentally, natural sciences are defined as disciplines that deal only with natural events (i.e., independent and dependent variables in nature) using scientific methods."[12]

The term "natural science" is used to distinguish the subject from the social sciences, which apply the scientific method to study human behavior and social patterns; the humanities, which use a critical or analytical approach to study the human condition; and the formal sciences such as mathematics and logic, which use an a priori, as opposed to factual methodology to study formal systems.

Oceanography

[edit | edit source]

Oceanography studies the oceans, marine organisms, ecosystems, ocean currents, waves, the ocean floor, and chemical substances.

Physics

[edit | edit source]

Def. the nature and properties of "matter and energy and their interactions"[7] is called physics.

Many of the early laws begin to make sense and increase understanding of the phenomena observed when coupled to experimental and theoretical studies performed in a laboratory here on Earth under controlled conditions.

Standard condition for temperature and pressure: The most used standards are those of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

Psychology

[edit | edit source]

Psychology is a scientific study of the human mind and its functions, especially those affecting behavior in a given context. It can refer to the mental characteristics or attitude of a person or group, or the mental and emotional factors governing a situation or activity.

Sociology

[edit | edit source]

Sociology is the scientific study of society.

Theoretical sciences

[edit | edit source]Def. the practice of training people to obey rules or a code of behavior, using punishment to correct disobedience is called discipline.

Def. the controlled behavior resulting from such training as mentioned just above is called discipline.

Def. an activity or experience that provides mental or physical training is called a discipline.

Def. the disciplines or branches of learning, especially those "dealing with measurable or systematic principles ... the collective [disciplines] of study or learning acquired through the scientific method"[13] is called science.

The best way to ruin a potentially capable scientist is to require discipline.

Def. the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment is called science.

Def. a systematically organized body of knowledge on a particular subject is called science.

History of scientific events

[edit | edit source]

Def. a period of time that has already happened, in contrast to the present and the future is called a past.

Def.

- an occurrence; something that happens

- a point in spacetime having three spatial coordinates and one temporal coordinate,

- a possible action that the user can perform that is monitored by an application or the operating system, or

- a set of some of the possible outcomes; a subset of the sample space

is called an event.

Def.

- the aggregate of past events,

- the branch of knowledge that studies the past; the assessment of notable events,

- a set of events involving an entity,

- a record or narrative description of past events,

- the list of past and continuing medical conditions of an individual or family,

- a record of previous user events, especially of visited web pages in a browser, or

- something that no longer exists or is no longer relevant

is called history.

The following is a reverse chronology of various science events, structures, instruments and artifacts.

21st Century

[edit | edit source]Here on the Earth's surface the νe flux is about 1011 νe cm-2 s-1 in the direction of the Sun.[14]

"The total number of neutrinos of all types agrees with the number predicted by the computer model of the Sun. Electron neutrinos constitute about a third of the total number of neutrinos. [...] The missing neutrinos were actually present, but in the form of the more difficult to detect muon and tau neutrinos."[14]

20th Century

[edit | edit source]

Manned spaceflight on an individual basis has only been achieved with experimental aircraft such as the X-15.

19th Century

[edit | edit source]

The Covered Bridge on the right was built in 1867 near the town of Cedarburg, Wisconsin.

18th Century

[edit | edit source]

Taken from the observation platform at the top of the Jantar Mantar, the image on the right shows smaller architectural sundials. The Jantar Mantar is a collection of architectural astronomical instruments, built by Maharaja Jai Singh II at his then new capital of Jaipur between 1727 and 1733. The City Palace is behind then Govindji Temple. Nahargarh Fort is on the Hill.

17th Century

[edit | edit source]

The Keplerian Telescope was invented by Johannes Kepler in 1611.[15]

16th Century

[edit | edit source]

The images on the right shows the sphere without sighting tubes or any device for observing astronomical objects and dates from 1547.

15th Century

[edit | edit source]

The image at the right dating from c. 1480 shows the sphere without sighting tube or any device for observing astronomical objects.

14th Century

[edit | edit source]

The remains of a pre-Hispanic temazcal in the image on the right recently found in Mexico City helped archaeologists pinpoint the location of the ancient neighborhood of Temazcaltitlan.

"Mexico City stands on the ancient site of Tenochtitlán, which, by the late 15th century, had emerged as the bustling capital of the Aztec Empire. One of the city’s oldest neighborhoods was Temazcaltitlan, known as a spiritual hub for the worship of female deities."[16]

The "temazcal, as steam baths are called in the indigenous Nahuatl language, was found near Mexico City’s modern La Merced neighborhood. It is a domed structure, spanning about 16.5 feet long by 10 feet wide, and was made from adobe blocks and stucco-coated tezontle, a type of volcanic rock."[17]

"[Y]ou can see the tub or water pool for the steam bath, as well as one of the sidewalks that were part of it."[18]

"The area was known for at least one temazcal, mentioned in the Crónica Mexicáyotl by Hernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, a 16th-century Nahua nobleman who wrote about the ascendance and fall of the Aztec capital. According to Tezozómoc, a temazcal was built in the area to purify a noble girl named Quetzalmoyahuatzin; the neighborhood got its name, Tezozómoc notes, because “all the Mexicans bathed […] there.”"[16]

"Temazcaltitlan was associated with the worship of female deities of fertility, water, and pulque, a fermented agave drink with ancient roots; the Aztec goddess Mayahuel is often depicted with agave sap pouring from her breasts. The discovery of the temazcal, experts say, confirms the neighborhood’s status as a spiritual center."[16]

The image at the left shows a sceptre dated to before 1380.

13th Century

[edit | edit source]

The ruin tower on the right is apparently dated to the 13th Century and was built by the Anasazi.

12th Century

[edit | edit source]

Romanesque apses and brick towers of the Church of San Tirso, Sahagún, are shown on the right, dated to the 12th Century.

11th Century

[edit | edit source]

The star map on the right, which features a cylindrical projection, was published in 1092 and has a corrected position for the pole star using Shen Kuo's astronomical observations.[19]

10th Century

[edit | edit source]

Visby was founded in the 10th century, on the then independent Baltic Sea island of Gotland. The Hansaetic League formed it during ensuing centuries, during which it came to Denmark. In 1645, it came into Swedish occupation, in which it has remained until today.

There is more about lenses more recently from Visby, Gotland.

"What intrigues the researchers is that the lenses are of such high quality that they could have been used to make a telescope some 500 years before the first known crude telescopes were constructed in Europe in the last few years of the 16th century."[20]

"Made from rock-crystal, the lenses have an accurate shape that betrays the work of a master craftsman. The best example of the lenses measures 50 mm (2 inches) in diameter and 30 mm (1 inch) thick at its centre."[20]

"The [Visby] Gotland crystals provide the first evidence that sophisticated lens-making techniques were being used by craftsmen over a 1,000 years ago."[20]

9th Century

[edit | edit source]

There was an inscription which placed the foundation of the nilometer in 861.

Cobá is a former pre-Columbian Mayan city on the Yucatán Peninsula southeast of Valladolid located in the state of Quintana Roo, Mexico.

In Cobá, the temple pyramid Nohoch-Mul (also known as Castillo, or the climbing pyramid shown on the left) is 42 meters high.

The city was founded shortly after the beginning of the year and expanded into a city state that peaked between 600 and 800 (1400 and 1200 b2k).

8th Century

[edit | edit source]

The Dunhuang map from the Tang Dynasty of the North Polar region at right is thought to date from the reign of Emperor Zhongzong of Tang (705–710). Constellations of the three schools are distinguished with different colors: white, black and yellow for stars of Wu Xian, Gan De and Shi Shen respectively. The whole set of star maps contains 1,300 stars.

The Dunhuang Star Atlas, the last section of manuscript Or.8210/S.3326. It is "the oldest manuscript star atlas known today from any civilisation, probably dating from around AD 700. It shows a complete representation of the Chinese sky in 13 charts with over 1300 stars named and accurately presented."[21]

"The Dunhuang Star Atlas [above center] forms the second part of a longer scroll (Or.8210/S.3326) that measures 210 cm long by 24.4 cm wide and is made of fine paper in thirteen separate panels."[21]

"The first part of the scroll is a manual for divination based on the shape of clouds. The twelve charts showing different sections of the sky follow these. The stars are named and there is also explanatory text. The final chart is of the north-polar region. The chart is detailed, showing a total of 1345 stars in 257 clearly marked and named asterisms, or constellations, including all twenty-eight mansions."[21]

"The importance of the chart lies in both its accuracy and graphic quality. The chart includes both bright and faint stars, visible to the naked eye from north central China".[21]

7th Century

[edit | edit source]

Sambor Pre Kuk, with its N16 Sanctuary imaged on the right, is an archaeological complex formed by the remains of the city of Isanapura, the capital of the kingdom of Chenla, an immediate predecessor of the Khmer Empire (pre-Angkorian).

This city was built during the reign of Isanavarman I (616-635). At this time, several constructions, clear predecessors of Khmer architecture, were erected in Angkor.

Cantona is a Mesoamerican archaeological site in the state of Puebla, Mexico. It was a fortified city with a high urbanization level at prehispanic times, probably founded by Olmec-Xicalanca groups towards the late Classical Period. It sat astride an old trading route between the Gulf Coast and the Central Highlands and was a prominent, if isolated, Mesoamerican city between 600 and 1000 CE. After Chichimec's invasions in the 11th century, Cantona was abandoned.

Cantona's inhabitants were mainly agricultural farmers and traders, particularly for obsidian, obtained from Oyameles-Zaragoza mountains surrounding the city. Additionally, they may have been supplying the lowlands with a derivative of the maguey plant, pulque. Cantona's population is estimated at about 80,000 inhabitants at its peak.

Cantona may well be the largest prehispanic city yet discovered in Mesoamerica. Limited archaeological work has been done at the site, and only about 10% of the site can be seen. The Pre-Columbian settlement area occupies approximately 12 km², distributed in three units, of which the largest is at the south, with a surface of 5 km². The site comprises a road network with over 500 cobblestone causeways, more than 3,000 individual patios, residences, and 24 ball courts - more than in any other mesoamerican site. It has an elevated Acropolis over the rest of the city in which the main buildings of the city were built. This was used for the ruling elite and priests, and was where the temples of the most important deities where located. These impressive buildings were constructed with carved stones (one atop the other) without any stucco or cement mortar. Cantona certainly was built with a definite urban design and walkways connecting each and every part of the city. The "First Avenue" is 563 meters in length.

6th Century

[edit | edit source]

On the right is the Basilica Cistern in Constantinople, Turkey. It has been dated to the 6th century.

Dzibanche is an archaeological site which includes the Temple of the Owl pyramid. It is an ancient Maya site located in southern Quintana Roo, in the Yucatan Peninsula of southeastern Mexico.

Structures at Dzibanche include the Temple of the Captives, the Temple of the Lintels and the Temple of the Owl, on the left.

5th Century

[edit | edit source]

Ancient India was an early leader in metallurgy, as evidenced by the wrought-iron Pillar of Delhi in the image on the right, dated to about 415 or 1585 b2k.

4th Century

[edit | edit source]

The House of Peter in Capernaum, Israel, has been dated to the 4th century.

3rd Century

[edit | edit source]The last known celestial globe shown at the right dates from 1850 to 1780 b2k. The constellation illustrations from the Mainz celestial globe are shown at the left.

2nd Century

[edit | edit source]

On the right is an image of the oldest extant diagram of Euclid's Elements, found at Oxyrhynchus and dated to c. 100 AD.[22]

1st Century

[edit | edit source]Pompeii lens (plano-convex) from the excavations of the Via Stabia, "House of the Engraver" dated to 79 AD per E. Gerspach, L'art de la verrerie (Paris 1885) 41-42.

Roman London lens (fragmentary biconvex glass lens of light green color), from Roman London, dated to 43-50 AD per H. Syer Cuming, "On Spectacles," The Journal of the British Archaeological Association 11 (1855) 144-49.

1st Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The "Late La Tène time span [is] between the conquests of 55 BC and 54 BC [2055 and 2054 b2k] under Julius Caesar (100-44 BC) and the time of Christ. In the rare cases where pottery and tableware are attributed to Saxons of the 4th/5th c. AD, "astonishingly La Tène art styles [more than 300 years out of fashion] re-emerge as dominant in the northern and western zone." (Hines 1996, 260)"[23]

"Stamped pottery has had a long and varied history in Britain. There have been periods when it flourished and periods when it almost totally disappeared. This article considers two variations of the rosette motif (A 5) and their fortunes from the late Iron Age to the Early Saxon period. [...] The La Tène ring stamps [which end in the 1st century BC; GH ] are found in a range of designs, from the simple negative ring (= AASPS Classification A 1bi) to four concentric negative rings (= AASPS A 2di). These motifs are also found in the early Roman period [1st century AD; GH]. [...] The 'dot rosettes' (= AASPS A 9di) on bowls from the [Late Latène] Hunsbury hill-fort (Fell 1937) use the same sort of technique as the dimple decoration on 4th-century 'Romano-Saxon' wares."[24]

In "Šarnjaka kod Šemovca (Dalmatia/Croatia), e.g., contain 700-year-older La Tène and Imperial period items (1st century BC to 3rd century AD) [...]:"[23]

"A large dugout house (SU 9) was discovered in the course of the investigation in 2006. Its dimensions are 4.8 by 2.1 metres, with a depth of 34 centimetres, and an east-west orientation, deviating slightly along the NE-SW line. It contained numerous sherds of Early Medieval pottery, two fragments of glass, and a small iron spike. Three sherds of Roman pottery [1st-3rd c. CE; GH] and ten sherds of La Tène pottery [ending 1st c. BCE; GH] were also recovered from the house."[25]

"The contemporaneity of Rome’s Imperial period textbook-dated to the 1st-3rd century AD with the Early Middle Ages (8th-10th century AD) is also confirmed for Poland [in the stratigraphic table above]. There, too, Late Latène (conventionally ending 1st c. BC) immediately precedes the Early Medieval period of the 8th-10th c. CE."[23]

"In [the Roman Empire] capital cities, Rome and Constantinople (Heinsohn 2016) [they] build residential quarters, streets, latrines, aqueducts, ports etc. only in one of the three periods—Imperial Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and Early Middle Ages—dated between 1 and 930s AD. In Rome, they are assigned to Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd c.); in Constantinople, to Late Antiquity (4th-6th c.)."[23]

"Roman churches of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages [...] would suffice to confirm the existence of these two periods. The churches are there. However, we never find churches of the 8th or 9th century superimposed on churches of the 4th or 5th century that, in turn, are superimposed on pagan basilicas of the 1st or 2nd century. They all share the same stratigraphic level of the 1st and 2nd/early 3rd century. Moreover, the ground plans of the 4th/5th—as well as the 8th/9th—century churches slavishly repeat the ground plans of 1st/2nd century basilicas, as already pointed out 75 years ago by Richard Krautheimer (1897-1994). It is this period of Imperial Antiquity (with its internal evolution from the 1st to 3rd centuries) that alone builds the residential quarters, latrines, streets, and aqueducts so desperately looked for in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Thus, Rome does not have more stratigraphy for the first millennium AD than England or Poland."[23]

"Germanic tribes, not only Anglo-Saxons and Frisians but also Franks, had been competing with Rome for the conquest of the British Isles since the 1st century BC".[23]

"1st century BC "Astonishingly LA TÈNE art styles" (Hines 1996) dominate pottery of SAXONS [and] Powerful LA TÈNE Celts with King Aththe-Domarous of Camulodunum [is the] greatest ruler."[23]

"Saxons begin their attack on Britain as early as the 1st century BC. They compete with the Romans, who may have employed Germanic Franks as auxiliary forces. The Saxons invade from the East, i.e., from the German Bight."[23]

From "the stratigraphy of the Saxon homeland, located around Bremen/Weser inside today’s Lower Saxony [it] is mainly inhabited by Chauci and Bructeri [...] Saxon tribes that are [...] at war with the Romans in the time of Augustus (31 BC-14 AD) and Aththe-Domaros of Camulodunum (Aθθe-Domaros, also read as Addedom-Arus; c. 15-5 BC)."[23]

On the right is an Indian-standard coin of King Maues. On the obverse is a rejoicing elephant holding a wreath, a symbol of victory. The Greek legend reads ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΜΑΥΟΥ (Great King of Kings Maues). The reverse shows the seated king Maues. Kharoshthi legend: RAJATIRAJASA MAHATASA MOASA (Great King of Kings Maues).

2nd Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The "fragments [of the Antikythera Mechanism] contain at least 30 interlocking gear-wheels, along with copious astronomical inscriptions. Before its sojourn on the sea bed, it computed and displayed the movement of the Sun, the Moon and possibly the planets around Earth, and predicted the dates of future eclipses."[26]

The Winged Nike of Samothrace is made from Parian marble, ca. 190 BC? and found in Samothrace in 1863 by the archaeological expedition of Charles Champoiseau, 1863 and 1879.

Cleopatra II on the left was involved in the ruling of Egypt apparently from c. 175 BC to until she died in 116 BC.

3rd Century BC

[edit | edit source]

A Sea Island survey diagram shown on the right was first written of by the Chinese mathematician Liu Hui during the Three Kingdoms era (220–280 CE).

"Jastorf (La Tène) culture [3rd to 1st century BC] with bronze and iron technology. Rich building evidence in downtown Bremen."[23]

"About 280 B.C. [2280 b2k], ... Aristarchus of Samos proposed the hypothesis that the Sun is at rest, while the Earth and the planets rotate about the Sun."[27] "Aristarchus also figured out how to measure the distances to the Sun and the Moon and their sizes."[28]

The celestial sphere may have been produced very early: According to records, the first celestial globe was made by Geng Shou-chang (耿壽昌) between 70 BC and 50 BC. In the Ming Dynasty, the celestial globe at that time was a huge globe, showing the 28 mansions, celestial equator and ecliptic. None of them have survived.

4th Century BC

[edit | edit source]A 3rd century BCE dioptra in the image at the right is an astronomical and surveying instrument, a sighting tube if fitted with protractors, it could be used to measure angles.

5th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

Edzná is a Mayan archaeological site in the north of the Mexican state of Campeche.

The Gran Acropolis is on the right.

Edzná was already inhabited in 400 BC (2400 b2k).

Apparently construction on the Parthenon is dated to have begun in 447 BC (2447 b2k) and was completed in 438 BC (2438 b2k) although decoration continued until 432 BC (2432 b2k).

6th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

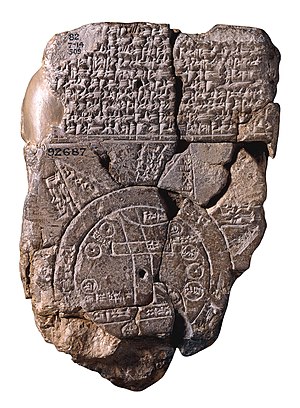

The map on the right shows Assyria, Babylonia and Armenia.

Croesus, 595 BC – c. 546 BC, was king of Lydia for apparently 14 years: from 560 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 546 BC, or 547 BC. He issued gold-silver alloy coins as on the left.

Based on the pottery shown in the image on the right, Croesus was burned to death.

"Sappho of Eresos" is shown center holding a lyre and plectrum, and turning toward a bearded man with a lyre partially visible on the left.

On the right is Becán, Structure IX from the top of Structure VIII. Becan is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Becan is located near the center of the Yucatán Peninsula, in the present-day Mexican state of Campeche. The name Becan was bestowed on the site by archaeologists who rediscovered the site, meaning "ravine or canyon formed by water" in Yukatek Maya, after the site's most prominent and unusual feature, its surrounding ditch.

Archaeological evidence shows that Becan was occupied in the middle Pre-Classic period, about 550 BCE, and grew to a major population and ceremonial center a few hundred years later in the late Preclassic. The population and scale of construction declined in the early classic (c 250 CE), although it was still a significant site, and trade goods from Teotihuacan have been found. A ditch and ramparts were constructed around the site at this time. There is a ditch that runs the circumference of the city which covers approximately 25 hectares. Around 500 the population again increased dramatically and many large new buildings were constructed, mostly in the Rio Bec style of Maya architecture. Construction of major buildings and elite monuments stopped about 830, although ceramic evidence shows that the site continued to be occupied for some time thereafter, although the population went into decline and Becan was probably abandoned by about 1200.

7th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

Amulet in the image on the right dates from 800 BC-612 BC for warding off plague.

Esarhaddon, portrayed on a stone stele, dated after 671 BC on the right, apparently ruled Assyria between 681 – 669 BC.

The black basalt monument of king Esarhaddon on the left narrates Esarhaddon's restoration of Babylon, ca. 670 BCE, from Babylon, Mesopotamia, Iraq, now in The British Museum, London.

8th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

Nimrud lens is plano-convex, Neo-Assyrian, from the North West Palace, Room AB, dated to 750–710 BC, discovered by Austen Henry Layard at the Assyrian palace of Nimrud, in modern-day Iraq.[29]

The ""Loupe of Sargon," a piano-convex rock-crystal lentoid [was] excavated by Layard at Nimrud in the 1850s [on the right].28 The object is oval (40 x 35 mm) and of uneven thickness (max. th. 22.5 mm) [centered and including the maximum convexness as shown edge-on in the image on the left. Its focal length has been calculated at 112.5 mm. Its nominal magnification is about 2 x but, owing to its imperfect surface, it would be useless as a tool."[30]

This Dipylon Vase on the right is apparently from the late Geometric period, or the beginning of the Archaic period, c. 750 BC (2750 b2k). Prothesis scene is exposure of the dead and mourning.

The low-relief from the L wall of the palace of Sargon II at Dur Sharrukin in Assyria (now Khorsabad in Iraq) is apparently dated to c. 716–713 BC. It is the image on the left.

In the center is an image of the upper portion of a statue of Elissa, Queen of Carthage, apparently from the early 8th century or late ninth century.

"The founding of the Phoenician colony of Toscanos would have come a bit later; its earliest levels (Strata I/II) would date from the years 805–780 cal BC.6"[31]

9th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

In 842 BC the Kingdom of Israel and the Phoenician cities sent tributes to Shalmaneser III. The image on the right is from the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III and depicts King Jehu of the Kingdom of Israel bowing before Shalmaneser III of Assyria.

Carthage was founded in 814 BC.[32]

"The recent radiocarbon dates from the earliest levels in Carthage situate the founding of this Tyrian colony in the years 835–800 cal BC,4 which coincides with the dates handed down by Flavius Josephus and Timeus for the founding of the city."[31]

The "dates for the founding of Carthage coincide with dates established for the Phoenician colony of Morro de Mezquitilla, which situate the most ancient occupation levels (Strata B1a and B2) in the years 807–802 cal BC.5"[31]

The "founding of the first Phoenician colonies at the end of the ninth century coincides with the radio-carbon chronology attributed to the most ancient Phoenician imports recorded in the indigenous Portuguese settlements and in the south of Spain, like Acinipo, Alcáçova de Santarem or Cerro de la Mora.7"[31]

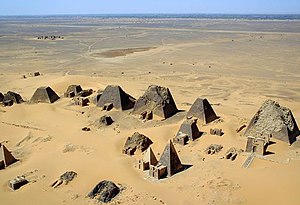

On the right is an aerial view of the Nubian pyramids at Meroe in 2001, which apparently date from 2800 to 2280 b2k. The pyramid in the center is from this grouping.

On the left is apparently the second set of Nubian pyramids of the Island of Meroe in the Sudan.

10th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The 10th century BC is equivalent to 3,000 to 2,900 b2k.

On the right is the burial mask for the Pharaoh Psusennes I exhumed from Tomb III at Tanis (Nile delta). The material used is gold (different pieces were assembled using nails). The eyebrows and eye shadows are lapis lazuli. The eyes are glass paste. There is a cobra on the forehead. The ritual beard is braided to symbolize the death of the sovereign. It is kept in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo. Dynasty is the XXI, dated to c. 1039 BC-990 BC.

In the left image is the burial mask for pharaoh Amenemope of the 21st Dynasty of Egypt, dated to 1001 – 992 BC or 993 – 984 BC.

11th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The iron age history period began between 3,200 and 2,100 b2k.

The Guanches are believed to be the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands perhaps as early as 3,000 b2k.

The first image down on the right is one of the Pyramids of Guimar, Canary Islands.

The "Guanches built several small step pyramids on the islands, using the same model as those found in ancient Egypt and in Mesopotamia."[33]

"The pyramids have an east-west alignment which also indicates that they probably had a religious [or astronomical] purpose, associated with the rise and setting of the sun."[33]

"Carefully built stairways on the west side of each pyramid lead up to the summit, which in each case has a flat platform covered with gravel, possibly used for religious or ceremonial purposes."[33]

They "shared a number of cultural characteristics with the ancient Egyptians and [...] their building style appears to have been replicated in South and Central America."[33]

The mummies on the left have red hair, the third down has blonde, and other Nordic features of the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands.

"An examination of one of the mummies' bodies showed incisions that virtually matched those found in Egyptian mummies, although the string used by the Guanche embalmers to close the wounds was much coarser than would have been used by the Egyptian experts."[33]

"Like the Celtic Tocharians, the finest evidence of what the original Guanche looked like, is in the fortuitous existence of original Guanche mummies, which are on public display in that island group's national museum."[33]

"As the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands were fair-haired and bearded, it was possible [...] that long before the 15th Century, people of the same stock as those who settled the Canary Islands, also sailed the same route along the Canary Current that took Christopher Columbus to the Americas."[34]

"According to the Aztec and Olmec (Central American Amerind) legends, their god, Quetzalcoatl, had Nordic features (eyes and hair color) and a beard. This god came from over the sea and taught the Amerinds how to raise corn and build structures."[33]

"The existence of the red-haired Guanches on the Canary Islands, combined with the red-haired pre-Columbus mummies found in South America and the marked similarity in pyramid building styles, indicate that an over the atlantic people probably used the Canaries Current to cross the Atlantic, most likely between 2000 and 500 BC."[33]

"The original occupants of the Canary Islands were a native people called the Guanche. Their mummies have been found with red hair and blond hair. Reportedly, the men were around 7 feet and the women around 6 feet."[35] Massive "walls, hydraulic systems and road systems on the island of Mauritius, [...] are connected with the pyramid complexes that have been rediscovered there in recent months."[36]

"Since all these structures are in the same general area of the seven pyramids that have been discovered on the island, it is reasonable to conclude that everything was probably built by the same civilisation – and that this was done a long time ago."[36]

"As for the structure of the pyramids on this island off the coast of Africa, they are platform pyramids made of volcanic rock with other stones worked into them, similar in design and size to the pyramids on Tenerife, in the Canary Islands."[36]

"In the vicinity of these seven pyramids, in a zone that is about two square kilometres in size, near the villages of Plaine Magnien, the cemetery and Mahebourg, there are massive rock walls, constructed with the same techniques and from the same material as the pyramids."[36]

"There are also paved roadways that connect the pyramids to other remarkable structures. The roads are perfectly flat and of such design that the trucks that use them every day cause little damage."[36]

"The long-held notion that the pyramids were built only in Egypt and Mexico had to change in the 20th century. It was discovered that stone and brick structures in the shape of the pyramid were built thousands of years ago from Bolivia and Peru through Central American countries of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Belize as well as throughout the islands of the coasts of Africa such as Canary Islands and Mauritius, then Sudan, Southern European countries such as Italy, France and Greece and in the east in China, Korea and Pacific islands."[37]

"In Mauritius the stony soils form an integral part of the industry,5 though often stones are so numerous that they are piled into walls and pyramids, and in parts cultivation is possible only by muraille creole-one row of canes, one of stones- a system that has some advantages for moisture conservation in dry areas."[38]

"It goes without saying that the theory that these are merely heaps of stones is totally absurd, especially when you show them to geologists and engineers. For one thing the precision of the corner angles of these monuments [especially shown in the image on the right] seen from space is unmistakable, and there is no way this could be the work of slaves clearing useless stones from the fields and heaping them up, even artistically. The precision of the corners and bases, and the allowances made for the sometimes uneven ground, demand calculations and execution by experienced architects."[36]

The "Madalena pyramidal structures, known by the locals as “maroiços,” are analogous to similar protohistoric structures found in Sicily, North Africa and the Canary islands which are known to have served ritual purposes."[39]

12th Century BC

[edit | edit source]Between 1200 BC and 1000 BC diffusion in the understanding of iron metallurgy and use of iron objects was fast and far-flung. Anthony Snodgrass[40][41] suggests that a shortage of tin, as a part of the Bronze Age collapse and trade disruptions in the Mediterranean around 1300 BC, forced metalworkers to seek an alternative to bronze. As evidence, many bronze implements were recycled into weapons during that time. More widespread use of iron led to improved steel-making technology at lower cost. Thus, even when tin became available again, iron was cheaper, stronger and lighter, and forged iron implements superseded cast bronze tools permanently.[42]

13th Century BC

[edit | edit source]By the Middle Bronze Age increasing numbers of smelted iron objects (distinguishable from meteoric iron by the lack of nickel in the product) appeared in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and South Asia. African sites are turning up dates as early as 1200 BC.[43][44][45]

14th Century BC

[edit | edit source]Schliemann lenses (plano-convex), found at Troy, dated to 1334-1184 BC per V. Tolstikov and M. Treister, The Gold of Troy: Searching for Homer's Fabled City (London 1996) nos. 176-216, 230.

15th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

"Three bossed crystal discs" (plano-convex), from the Late Minoan II-IIIA, Mavrospelio cemetery, dated to 1425-1340 BC per E. J. Forsdyke, "The Mavro Spelio Cemetery at Knossos," BSA 28 (1926-1927) 243-96, esp. 288.

16th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The Late Bronze Ages begin about 3550 b2k and end about 2900 b2k.

The Pátzcuaro Basin is "on the Central Mexican Altiplano [19° 36′ N 101° 39′ W 2,033–3,000 meters above sea level (m asl)] [...] The earliest occupation is indicated by maize pollen in lake cores [sometime between 1690 and 940 B.C. (43, 47, 49)]."[46]

The "abandonment of lakeshore Swiss pile-dwellings has been dated to around 1520 BC [3520 b2k] (Menotti 2001). [Slightly] "later in time episodes of flood events and lake-level highstand at 3100 BP (1415/1311 2σ cal. BC) and 2800 BP (996/914 2σ cal. BC) have been recently detected in the Southern Alps, in the sediment cores extracted from the Lake Ledro, located in the province of Trento (Joannin et al. 2014)."[47] Radiocarbon "data indicate that the New Kingdom of Egypt started between 1570 and 1544 B.C.E [3570 - 3544 b2k]."[48]

High precision radiocarbon dating of 18 samples from Jericho, including six samples of carbonized cereal from the burnt stratum, gave the age of the strata as 1562 BC, with a margin of error of 38 years [3562 ± 38 b2k].[49]

17th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The Trundholm Sun chariot pulled by a horse is a sculpture imaged at left and right dated by the Nationalmuseet to about 1800 to 1600 BCE (3800 to 3600 b2k).

Evans lenses (plano-convex) are Middle Minoan IIIB, from the Temple Repositories at Knossos, along with a "royal Draught Board" with ivory and crystal inlays backed with silver foil, dated to 1640-1600 BC, Minoan civilization per A. Evans, The Palace of Minos I (London 1921) 469-72; cf. the eye of the steatite bull's-head rhyton from the Little Palace at Knossos: Evans, The Tomb of the Double Axes etc (London 1914) 82.

The Fisherman is a Minoan Bronze Age fresco from Akrotiri, on the Aegean island of Santorini (classically Thera), dated to the Neo-Palatial period (c. 1640–1600 BC). The settlement of Akrotiri was buried in volcanic ash (dated by radiocarbon dating to c. 1627 BC [c. 3626 b2k]) by the Minoan eruption on the island, which preserved many Minoan frescoes like this.

19th Century BC

[edit | edit source]Souckova-Siegolová (2001) shows that iron implements were made in Central Anatolia in very limited quantities around 1800 BC and were in general use by elites, though not by commoners, during the New Hittite Empire (∼1400–1200 BC).[50]

Similarly, recent archaeological remains of iron working in the Ganges Valley in India have been tentatively dated to 1800 BC. Tewari (2003) concludes that "knowledge of iron smelting and manufacturing of iron artifacts was well known in the Eastern Vindhyas and iron had been in use in the Central Ganga Plain, at least from the early second millennium BC".[51]

20th Century BC

[edit | edit source]The Iron Age in the Ancient Near East became known with the discovery of iron smelting and smithing techniques in Anatolia or the Caucasus and Balkans in the late 2nd millennium BC (c. 1300 BC).[52]

21st Century BC

[edit | edit source]In the Black Pyramid of Abusir, dating before 2000 BC, Gaston Maspero found some pieces of iron. In the funeral text of Pepi I, the metal is mentioned.[53] A sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah as well as a battle axe with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit.[54] Tutankhamun's meteoric iron dagger with an iron blade was found in Tutankhamun's tomb, 13th century BC, was recently examined and found to be of meteoric origin.[55] The "blade’s composition of iron, nickel and cobalt was an approximate match for a meteorite that landed in northern Egypt. The result “strongly suggests an extraterrestrial origin"".[56][57]

"In Berber, the name "Siwa" means "prey bird and protector of sun god Amon-Ra." It is derived from the name of the indigenous inhabitants, Tiswan, who speak Tassiwit, a dialect related to Berber spoken in the Sahara and North Africa. Siwa is one of the most arid oases in western Egypt near the border of Libya at a depression of 18 meters below sea level, and it is 300 kilometers southwest of the Mediterranean port city of Marsa Matruh. The oasis is 82 kilometers long and has a width ranging between 2 and 20 kilometers. The oasis was occupied since Paleolithic and Neolithic times. It was first mentioned more than 2,500 years ago in the records of the pharaohs of the Middle and New Kingdoms (2050-1800 B.C. and 1570-1090 B.C.)"[58]

23rd Century BC

[edit | edit source]The earliest tentative evidence for iron-making is a small number of iron fragments with the appropriate amounts of carbon admixture found in the Proto-Hittite layers at Kaman-Kalehöyük and dated to 2200–2000 BC. Akanuma (2008) concludes that "The combination of carbon dating, archaeological context, and archaeometallurgical examination indicates that it is likely that the use of ironware made of steel had already begun in the third millennium BC in Central Anatolia".[59]

27th Century BC

[edit | edit source]Egyptian lenses of the IV/V Dynasties, in Egypt, are eyes in funerary statues, dated to 2620-2400 BC.[60]

30th Century BC

[edit | edit source]In the Mesopotamian states of Sumer, Akkad and Assyria, the initial use of iron reaches far back, to perhaps 3000 BC.[53] One of the earliest smelted iron artifacts known was a dagger with an iron blade found in a Hattic tomb in Anatolia, dating from 2500 BC.[61]

31st Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The pyramid on the right may be earlier than 5,000 b2k.

33rd Century BC

[edit | edit source]Artemision lenses (plano-concave), Archaic levels, the Artemision of Ephesos, dated to 3300-1200 BC per D.G. Hogarth, Excavations at Ephesus: The Archaic Artemisia (London 1908) 210-11, pl. 46.

32nd Century BC

[edit | edit source]"The earliest known iron artefacts are nine small beads securely dated to circa 3200 BC, from two burials in Gerzeh, northern Egypt."[62]

"Since both tombs are securely dated to Naqada IIC–IIIA, c 3400–3100 BC (Adams, 1990: 25; Stevenson, 2009: 11–31), the beads predate the emergence of iron smelting by nearly 2000 years, and other known meteoritic iron artefacts by 500 years or more (Yalçın 1999), giving them an exceptional position in the history of metal use."[62]

The image on the left uses neutron radiography to show the metal underneath the corrosion.

"Bead UC10738 [in the image on the right] has a maximum length of 1.5 cm and a maximum diameter of 1.3 cm, bead UC10739 is 1.7 cm by 0.7 cm, and bead UC10740 is 1.7 cm by 0.3 cm. All three beads are of rust-brown colour with a rough surface, indicative of heavy iron corrosion. Initial analysis by [proton–induced X–ray fluorescence] pXRF indicated an elevated nickel content of the surface of the beads, in the order of a few per cent, and their magnetic property suggested that iron metal may be present in their body (Jambon, 2010)."[62]

36th Century BC

[edit | edit source]"c. 3500 B.C. Phoenicians cooking on sand discover glass."[63]

"Natural glass has existed since the beginnings of time, formed when certain types of rocks melt as a result of high-temperature phenomena such as volcanic eruptions, lightning strikes or the impact of meteorites, and then cool and solidify rapidly. Stone-age man is believed to have used cutting tools made of obsidian (a natural glass of volcanic origin also known as hyalopsite, Iceland agate, or mountain mahogany) and tektites (naturally-formed glasses of extraterrestrial or other origin, also referred to as obsidianites)."[64]

"According to the ancient-Roman historian Pliny (AD 23-79), Phoenician merchants transporting stone actually discovered glass (or rather became aware of its existence accidentally) in the region of Syria around 5000 BC [7,000 b2k]. Pliny tells how the merchants, after landing, rested cooking pots on blocks of nitrate placed by their fire. With the intense heat of the fire, the blocks eventually melted and mixed with the sand of the beach to form an opaque liquid."[64]

"The earliest man-made glass objects, mainly non-transparent glass beads, are thought to date back to around 3500 BC, with finds in Egypt and Eastern Mesopotamia. In the third millennium, in central Mesopotamia, the basic raw materials of glass were being used principally to produce glazes on pots and vases. The discovery may have been coincidental, with calciferous sand finding its way into an overheated kiln and combining with soda to form a coloured glaze on the ceramics. It was then, above all, Phoenician merchants and sailors who spread this new art along the coasts of the Mediterranean."[64]

40th Century BC

[edit | edit source]

"It is also only within recent years that the discovery of a seminal black kingdom in the Nile Valley, predating the Egyptian dynasties, has settled the question, once and for all, of the roots of classical Egyptian culture and technology (see Journal of African Civilizations, vol. 4, no. 2, November 1982)."[65]

“The Great Pyramid stands on the northern edge of the Giza Plateau, [60.4 m] 198 feet above sea level”.[66]

A step pyramid exists in the archaeological site of Monte d'Accoddi, in Sardinia, dating to the 4th millennium BC, shown in the image on the right: "a trapezoidal platform on an artificial mound, reached by a sloped causeway. At one time a rectangular structure sat atop the platform ... the platform dates from the Copper Age (c. 2700–2000 BC), with some minor subsequent activity in the Early Bronze Age (c. 2000–1600 BC). Near the mound are several standing stones, and a large limestone slab, now at the foot of the mound, may have served as an altar."[67]

41st Century BC

[edit | edit source]

The original structure shown in left and right images may have been built by the Ozieri culture or earlier c. 4,000-3,650 BC.

Paleolithic workshops on Sardinia suggest a hominin presence in Sardinia between 450,000 and 10,000 years ago.

During the last ice age sea levels were likely lower than 200 meters, at that time Sardinia and Corsica formed a single large island, separated from Tuscany by a narrow arm of sea, marked in yellow between Sardinia and Tusscany, perhaps below 1,000 m in depth during the last ice age.

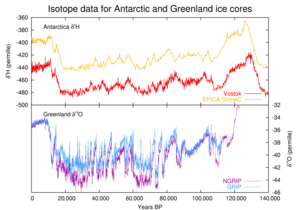

Comparison of temperature proxies for ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland for 140,000 years are shown on the left. Greenland ice cores use delta 18O, while Antarctic ice cores use delta 2H. Note that the Dansgaard-Oeschger events in the Greenland ice core between 20,000 and 110,000 years ago barely register (if at all) in the corresponding Antarctic record.

45th Century BC

[edit | edit source]"In the Chalcolithic/earliest Bronze Age I period (c. 4500±3000 cal BC), copper was mined in open galleries from the massive brown sandstone deposit, which consisted of thick layers of the copper carbonate malachite and chalcocite, a copper sulphide."[68]

50th Century BC

[edit | edit source]"An archaeological site in [Serbia] has shown its metal. This ancient settlement contains the oldest securely dated evidence of copper making, from 7,000 years ago, and suggests that copper smelting may been invented in separate parts of Asia and Europe at that time rather than spreading from a single source."[69]

55th Century BC

[edit | edit source]"Until now, experts said that only stone was used in the Stone Age and that the Copper Age came a bit later. Our finds, however, confirm that metal was used some 500 to 800 years earlier, [which indicates that humans were using metals in Europe by 7,500 years ago]."[70]

Hypotheses

[edit | edit source]- The sciences do not need to follow the humanities, religion, or the arts to be beneficial to humanity.

- The scientific method is not a recent occurrence.

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Wilson, EO. 1998. Consilience: The unity of knowledge. New York. Alfred A. Knopf. p334

- ↑ Griffith J. 2011. What is Science?. In The Book of Real Answers to Everything!, ISBN 9781741290073. http://www.worldtransformation.com/what-is-science/ accessed November 20, 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jennifer Viegas (3 December 2014). Oldest Art Was Carved Onto Shell 540,000 Years Ago. Discovery.com. http://news.discovery.com/human/evolution/oldest-art-was-carved-onto-shell-540000-years-ago-141203.htm. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Renfrew and Bahn (2004 [1991]:13)

- ↑ McPherron, S. P., Z. Alemseged, C. W. Marean, J. G. Wynn, D. Reed, D. Geraads, R. Bobe, and H. A. Bearat. 2010. Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 466:857-860

- ↑ Jim Derby (8 January 2014). architecture. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/architecture. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Philip B. Gove, ed (1963). Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: G. & C. Merriam Company. pp. 1221.

- ↑ Mark R. Mireles; Kirth L. Pederson; Charles H. Elford (February 21, 2007). Meteorologial Techniques. Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, USA: Air Force Weather Agency/DNT. http://oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA466107. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

- ↑ What is Chemistry?. Chemweb.ucc.ie. http://chemweb.ucc.ie/what_is_chemistry.htm. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ↑ Chemistry. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ earth science. http://www.memidex.com/earth-science. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Stephen F. Ledoux (2002). "Defining Natural Sciences" (PDF). Behaviorology Today 5 (1): 34. http://behaviorology.org/pdf/DefineNatlSciences.pdf.

- ↑ Widsith (20 August 2006). science. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/science. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 John N. Bahcall (April 28, 2004). Solving the Mystery of the Missing Neutrinos. Nobel Media AB. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/themes/physics/bahcall/. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ↑ AH Tunnacliffe, JG Hirst (1996). Optics. Kent, England. pp. 233–7. ISBN 0-900099-15-1.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Brigit Katz (24 January 2020). "14th-Century Steam Bath Found in Mexico City". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ↑ George Dvorsky (24 January 2020). "14th-Century Steam Bath Found in Mexico City". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ↑ Martes (21 January 2020). "Hallazgo en inmediaciones de La Merced confirma ubicación del barrio prehispánico de Temazcaltitlan". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ↑ Joseph Needham (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. pp. 208.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 David Whitehouse (April 5, 2000). Did the Vikings make a telescope?. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/702478.stm. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 British Library (June 2015). The Dunhuang Star Atlas. British Library: International Dunhuang Project (IDP). http://idp.bl.uk/4DCGI/education/astronomy/atlas.html. Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- ↑ Bill Casselman. One of the Oldest Extant Diagrams from Euclid. University of British Columbia. http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/Euclid/papyrus/papyrus.html. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 Gunnar Heinsohn (15 June 2017). "ARTHUR OF CAMELOT AND ATHTHE-DOMAROS OF CAMULODUNUM: A STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING A NEW CHRONOLOGY FOR 1st MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND". Quantavolution Magazine. http://www.q-mag.org/arthur-of-camelot-and-aththe-of-camulodunum.html. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- ↑ D.C. Briscoe (2016). "Two Important Stamp Motifs in Roman Britain and Thereafter, In: Romano-British Pottery in the Fifth Century". Internet Archaeology (41). doi:https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.41.2.

- ↑ L. Bekić (2016). "Nalazi 8. i 9. stoljeća sa Šarnjaka kod Šemovca / Finds from the 8th and 9th centuries at Šarnjak near Šemovec". Vjesnik Arheološkog muzeja u Zagrebu (VAMZ) XLIX: 219-248.

- ↑ Jo Marchant (30 November 2006). "In search of lost time". Nature 444 (7119): 534-538. doi:10.1038/444534a. https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v444/n7119/full/444534a.html. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- ↑ B. L. van der Waerden (1974). "The Earliest Form of the Epicycle Theory". Journal for the History of Astronomy 5: 175-85. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//abs/1974JHA.....5..175V. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ D. Koutsoyiannis; A. N. Angelakis (2003). Hydrologic and Hydraulic Science and Technology in Ancient Greece, In: Encyclopedia of Water Science. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.. pp. 415-7. http://www.a-angelakis.gr/files/books/2002Encycl2WatResTechAncGreEntry2.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ David Whitehouse (July 1, 1999). World's oldest telescope?. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/380186.stm. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ↑ Dimitris Plantzos (July 1997). "Crystals and Lenses in the Graeco-Roman World". American Journal of Archaeology 101 (3): 451-64. http://www.hist-arch.uoi.gr/prosopiko/plantzos/Crystals.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Maria Eugenia Aubet (2008). Political and Economic Implications of the New Phoenician Chronologies. Universidad Pompeu Fabra. pp. 179. http://www.upf.edu/larq/_pdf/AubtCrono.pdf. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati (12 January 2001). Sabatino Moscati. ed. Colonization of the Mediterranean, In: The Phoenicians. I.B.Tauris. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-85043-533-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=1EEtmT9Tbj4C. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 History of White Race - Chapter 6 (2008). "To The Ends Of The Earth - Lost White Migrations". The Guanches of the Canary Islands. Bibliotecapleyades. http://www.white-history.com/hwr6a.htm. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Thor Heyerdahl (2008). "To The Ends Of The Earth - Lost White Migrations". The Guanches of the Canary Islands. Bibliotecapleyades. http://www.white-history.com/hwr6a.htm. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Sharon Day (18 March 2014). Canary Islands: Oddities and Coincidences?. Ghost Hunting Theories. http://www.ghosthuntingtheories.com/2014/03/canary-islands-oddities-and-coincidences.html. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 Antoine Gigal (2013). Megalithic walls and hydraulic systems linked with Mauritius pyramids. United Kingdom: Gigal Research. http://www.gigalresearch.com/uk/complexe-ile-maurice.php. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ↑ Semir Sam Osmanagich (25 August 2008). BOSNIAN VALLEY OF THE PYRAMIDS Discovery and Road to Recognition, In: The First International Scientific Conference Bosnian Valley of the Pyramids. Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina: the “Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun” Foundation. pp. 1-55. http://piramidasunca.ba/dokumentovano.com/piramida/dokumenti/referati/ICBP-Osmanagich-Paper-February_2009.pdf. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ↑ H. C. Brookfield (1959). "Problems of monoculture and diversification in a sugar island: Mauritius". Economic Geography 35 (1): 25-40. doi:10.2307/142076?journalCode=recg20. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2307/142076?journalCode=recg20. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ↑ Carolina Matos (28 August 2013). Pico: New archaeological evidence reveals human presence before Portuguese occupation – Azores. Portuguese American Journal. http://portuguese-american-journal.com/pico-new-archeological-evidence-reveals-human-presence-before-portuguese-occupation-azores/. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ A.M.Snodgrass (1966), "Arms and Armour of the Greeks". (Thames & Hudson, London)

- ↑ A. M. Snodgrass (1971), "The Dark Age of Greece" (Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh).

- ↑ Theodore Wertime and J. D. Muhly, eds. The Coming of the Age of Iron (New Haven, 1979).

- ↑ Duncan E. Miller and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa' Journal of African History 35 (1994) 1–36; Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' Current Anthropology 1968.

- ↑ How Old is the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa? – by Roderick J. McIntosh, Archaeological Institute of America (1999)

- ↑ Iron in Sub-Saharan Africa – by Stanley B. Alpern (2005)

- ↑ Christopher T. Fisher; Helen P. Pollard; Isabel Israde-Alcántara; Victor H. Garduño-Monroy; Subir K. Banerjee (April 2003). "A reexamination of human-induced environmental change within the Lake Pátzcuaro Basin, Michoacán, Mexico". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 100 (8): 4957-4962. doi:10.1073/pnas.0630493100. http://www.pnas.org/content/100/8/4957.long. Retrieved 2018-2-25.

- ↑ Giacomo Capuzzo (2014). SPACE-TEMPORAL ANALYSIS OF RADIOCARBON EVIDENCE AND ASSOCIATED ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD: FROM DANUBE TO EBRO RIVERS AND FROM BRONZE TO IRON AGES. BARCELONA, Spain: UNIVERSITAT AUTÒNOMA DE BARCELONA. pp. 416. https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/tesis/2014/hdl_10803_283401/gc1de1.pdf. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ↑ Christopher Bronk Ramsey; Michael W. Dee; Joanne M. Rowland; Thomas F. G. Higham; Stephen A. Harris; Fiona Brock; Anita Quiles; Eva M. Wild et al. (18 June 2010). "Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt". Science 328 (5985): 1554-1557. doi:10.1126/science.1189395. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/328/5985/1554. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ↑ Hendrik Bruins; Johannes van der Plicht (1995). "Tell-es-Sultan (Jericho): Radiocarbon results of short-lived cereal and multiyear charcoal samples from the end of the Middle Bronze Age". Radiocarbon 37 (2): 213-220. https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/radiocarbon/article/viewFile/1666/1670. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- ↑ Souckova-Siegolová, J. (2001). "Treatment and usage of iron in the Hittite empire in the 2nd millennium BC". Mediterranean Archaeology 14: 189–93..

- ↑ Tewari, Rakesh (2003). "The origins of Iron Working in India: New evidence from the Central Ganga plain and the Eastern Vindhyas". Antiquity 77: 536–545. http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/tewari/tewari.pdf.

- ↑ Jane C. Waldbaum, From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean (Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. LIV, 1978).

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Chisholm, H. (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica. New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co.

- ↑ Richard Cowen, The Age of Iron Chapter 5 in a series of essays on Geology, History, and People prepares for a course of the University of California at Davis. Online version

- ↑ Comelli, Daniela; d'Orazio, Massimo; Folco, Luigi; El-Halwagy, Mahmud (2016). "The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun's iron dagger blade". Meteoritics & Planetary Science (Wiley Online) 51 (7): 1301. doi:10.1111/maps.12664.Free full text available.

- ↑ Walsh, Declan (2 June 2016). "King Tut’s Dagger Made of ‘Iron From the Sky,’ Researchers Say". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/03/world/middleeast/king-tuts-dagger-made-of-iron-from-the-sky-researchers-say.html. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ Panko, Ben (2 June 2016). "King Tut’s dagger made from an ancient meteorite". Science. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/sifter/king-tut-s-dagger-made-ancient-meteorite. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Hsain Ilahiane (17 July 2006). Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Lanham, Maryland USA: The Scarecrow Press. pp. 360. ISBN 0810864908. https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0810864908. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ↑ Akanuma, Hideo (2008). "The Significance of Early Bronze Age Iron Objects from Kaman-Kalehöyük, Turkey". Anatolian Archaeological Studies 17: 313–320. http://www.jiaa-kaman.org/pdfs/aas_17/AAS_17_Akanuma_H_pp_313_320.pdf.

- ↑ Jay M. Enoch, Vasudevan Lakshminarayanan (March 2000). "Duplication of unique optical effects of ancient Egyptian lenses from the IV/V Dynasties: lenses fabricated ca 2620–2400 BC or roughly 4600 years ago". Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 20 (2): 126-30. doi:10.1046/j.1475-1313.2000.00496.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1475-1313.2000.00496.x/abstract. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ↑ Richard Cowen () The Age of Iron Chapter 5 in a series of essays on Geology, History, and People prepares for a course of the University of California at Davis. Online version.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Thilo Rehrena; Tamás Belgya; Albert Jambon; György Káli; Zsolt Kasztovszky; Zoltán Kis; Imre Kovács; Boglárka Maróti et al. (December 2013). "5,000 years old Egyptian iron beads made from hammered meteoritic iron". Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (12): 4785–92. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.002. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440313002057. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ↑ Larry Brown (2005). An early history of the telescope. From 3500 B.C. until about 1900 A.D.. Antique Telescopes. http://www.antiquetelescopes.org/history.html. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Infoserv (April 15, 2011). A Brief History of Glass. Artenergy Publishing S.r.l.. https://web.archive.org/web/20110415194738/http://www.glassonline.com/infoserv/history.html. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Ivan Van Sertima (2010). Ivan Van Sertima. ed. The Lost Sciences of Africa: An Overview, In: Blacks in Science: Ancient and Modern. Pscataway, New Jersey, USA: Transaction Publishers. pp. 5-26. ISBN 978-0-87855-941-1. http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=RqOz55ZBfdkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA5&ots=MJBIE2cQ8v&sig=N3hYQoGoqp3ShdiSX1TZppxe05E. Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- ↑ Petko Vidusa Nikolic, Petko Nikolic Vidusa (2005). The Great Pyramid and the Bible : Earth's Measurements. Kitchener, Canada: Mystik Book. pp. 65. ISBN 0973237147.

- ↑ Blake, Emma; Arthur Bernard Knapp (2004). The archaeology of Mediterranean prehistory. Wiley Blackwell. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-631-23268-1. https://books.google.com/?id=F15vfrJq8LUC&pg=PA117&dq=Monte+d%27Accoddi#v=onepage&q=Monte%20d%27Accoddi&f=false. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ↑ B.S. Ottaway (2001). "Innovation, production and specialization in early prehistoric copper metallurgy". European Journal of Archaeology 4 (1): 87-112. doi:10.1179/eja.2001.4.1.87. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/eja.2001.4.1.87. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ↑ Bruce Bower (17 July 2010). "Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers". ScienceNews. http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/60563/description/Serbian_site_may_have_hosted_first_copper_makers. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ↑ Julka Kuzmanovic-Cvetkovic (8 October 2008). Ancient axe find suggests Copper Age began earlier than believed. http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/india-news/ancient-axe-find-suggests-copper-age-began-earlier-than-believed_100105122.html. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

External links

[edit | edit source]- Bing Advanced search

- Google Books

- Google scholar Advanced Scholar Search

- JSTOR

- Lycos search

- NASA's National Space Science Data Center

- NCBI All Databases Search

- Office of Scientific & Technical Information

- PsycNET

- PubChem Public Chemical Database

- Questia - The Online Library of Books and Journals

- SAGE journals online

- The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System

- Scirus for scientific information only advanced search

- SIMBAD Astronomical Database

- SIMBAD Web interface, Harvard alternate

- Spacecraft Query at NASA

- SpringerLink

- Taylor & Francis Online

- WikiDoc The Living Textbook of Medicine

- Wiley Online Library Advanced Search

- Yahoo Advanced Web Search

{{Anthropology resources}}{{Archaeology resources}}{{Radiation astronomy resources}}{{Chemistry resources}}{{Geology resources}}{{History of science resources}}{{Materials science resources}}{{Physics resources}}