Geominerals/Sorosilicates

Def. any group of silicates that have structurally isolated double tetrahedra (the dimeric anion Si2O76-)[1] is called a sorosilicate.

"There are four distinct Si positions, all of which are tetrahedrally coordinated; one of the silicate tetrahedra is an acid silicate group: SiO

3(OH). The four Si tetrahedra form a linear [Si

4O

12(OH)] cluster [that is] a sorosilicate."[2]

Let 𝞍 be an unspecified anion.

"The silicate tetrahedra polymerize to form an [Si

4𝞍13, 𝞍:O2−

, OH−

] sorosilcate fragment. These sorosilicate fragments matchup with the large interstices between the strips of edge-sharing octahedra [...], linking to both the octahedra of adjacent strips and to the shared edge of the [Mn

2O

6] dimer of tetrahedra."[2]

"The detailed stereochemistry of extended [T

n𝞍(3n+1)], n > 2 sorosilicate clusters was considered by Hawthorne (1984)".[2]

All "sorosilicate clusters with n > 3 have acid tetrahedral groups."[2]

"Sorosilicate structures with short clusters ([Si

2𝞍7],

[Si

3𝞍10]) are based on sheets or walls of polyhedra (octahedra or octahedra and tetrahedra) that are cross-linked by sorosilicate clusters that extend perpendicular to the sheets. Sorosilicate structures with longer clusters ([T

6𝞍19] in medaite, Mn

6[VSi

5O

18(OH)], Gramaccioli et al. 1981) consist of sheets or ribbons of octahedra in which the sorosilicate cluster extends parallel to the sheets or ribbons. In ruizite (Ca

2Mn

2[Si

4O

11(OH)

2](OH)

2(H

2O)

2: Hawthorne 1984), discontinuous sheets of edge-sharing octahedra are linked by [Si

4𝞍13] clusters orthogonal to the sheets. On the other hand, in tiragalloite [Mn

4AsSi

3O

12(OH): Gramacciolei et al. 1979] and akatoreite, the sorosilicate clusters are oriented parallel to the sheets of octahedra, and show more structural affinity with the inosilicate structures, in which infinite (T𝞍3) chains generally extend parallel to sheets of edge-sharing octahedra. Thus the sorosilicate composition [T

4𝞍13] seems to be a transitional point between these two structural themes."[2]

Akatoreites

[edit | edit source]

Akatoreite has the chemical formula Mn2+

9Al

2Si

8O

24(OH)

8 and crystallizes in the triclinic system.[3][4][5][2]

Empirical formula: Mn2+

8.61Fe2+

0.19Mg

0.09Ca

0.05Al

2.09Si

7.75O

23.17(OH)

8.83.[4]

"Results of chemical analyses reported by Read & Reay (1971) indicate that akatoreite has the formula (Mn

8.61Fe

0.19Mg

0.08Ca

0.05)Al

2.09Si

7.75O

23.17(OH)

8.83."[2]

Common impurities: Ti,Fe,Mg,Ca.[3]

The International Mineralogical Association (IMA) symbol is Aka.[6]

Akatoreite is a sorosilicate.[3]

Geological setting: "in manganiferous potassium-rich felsic metavolcanics (Norberg, Sweden)."[3]

Occurrence: "as vitreous, orange-brown, massive to radiating twinned columnar aggregates in a manganiferous metachert and carbonate lens on the southeastern margin of the Haast Schist Group, South Island, New Zealand."[2]

Environment: "In a manganiferous metachert and carbonate lens in schists (Akatore Creek, New Zealand)".[4]

"Locality: In New Zealand, three km south of Akatore Creek, east Otago, South Island."[4]

Associated minerals at type locality: Alabandite, Apatite, Pyroxmangite, Quartz, Rhodochrosite, Rhodonite, Spessartine, Tinzenite, Todorokite.[3]

"Akatoreite is associated with rhodochrosite, rhodonite, spessartine, quartz, hübnerite, alabandite, pyroxmangite, tinzenite, apatite, psilomelane, pyrolusite and todorokite."[2]

Common associates: Ganophyllite - (K,Na,Ca)

2Mn

8(Si,Al)

12(O,OH)

32 · 8H

2O, Pyrolusite - Mn4+

O

2 and Rhodochrosite - MnCO

3.[3]

Åkermanites

[edit | edit source]

Structures of Ca

2CoSi

2O

7, Ca

2MgSi

2O

7, and Ca

2(Mg

0.55Fe

0.45)Si

2O

7 contain the double tetrahedra chain shown in the diagram on the left.

Allanites

[edit | edit source]

Allanite has the general formula A

2M

3Si

3O

12(OH), where the A sites can contain large cations such as Ca2+

, Sr2+

, and rare-earth elements, and the M sites admit Al3+

, Fe3+

, Mn3+

, Fe2+

, or Mg2+

among others.[7]

The age of allanite grains that have not been destroyed by radiation can be determined using different techniques.[8]

Allanite is usually black in color, but can be brown or brown-violet, often coated with a yellow-brown alteration product,[9] likely limonite.

It was discovered in 1810 and named for the Scottish mineralogist Thomas Allan (1777–1833).[10] The type locality is Aluk Island, Greenland,[11] where it was first discovered by Karl Ludwig Giesecke.

Allanite-(Ce)

[edit | edit source]Allanite-(Ce) has the formula (Ca, Ce)

2(Al, Fe2+

, Fe3+

)(SiO

4)(Si

2O

7)O(OH).[10]

Crystal system: Monoclinic.[10]

Mineral Group: Epidote group.[10]

Member of Allanite Group > Epidote Supergroup.[11]

Occurrence: An accessory in some granites and granite pegmatites, syenites, more rarely in gabbroic pegmatites. Rarely in schists, gneisses, and some contact metamorphosed limestones; a clastic component of sediments.[10]

Association: Epidote, muscovite, fluorite.[10]

Often slightly radioactive due to minor U and/or Th contents; therefore often metamict.[11]

The Ca analogue of uedaite-(Ce).[11]

Geological Setting:A common accessory mineral in many igneous rocks, particularly those that are felsic, and metamorphosed igneous rocks. Also in pegmatites, skarns, and tactites. Not common in volcanic rocks. A detrital mineral.[11]

Axinites

[edit | edit source]

2O

7 silicate groups are connected by two BO

4-tetrahdra. Credit: Bubenik.{{free media}}

Axinite-(Mg) or magnesioaxinite, Ca

2MgAl

2BOSi

4O

15(OH) magnesium rich, can be pale blue to pale violet[12]

| Composition | Ca 2(Mn2+ , Fe2+ , Mg)Al 2(BO 3)Si 4O 12(OH) |

| Class | Silicates (sorosilicates) |

| Crystal system | Triclinic |

| Mohs' hardness | 6-7.5 |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Cleavage | Good |

| Lustre | Vitreous |

| Streak | White |

| Geological Setting | Low to high grade regionally metamorphosed rocks, contact metamorphic rocks, pegmatites. |

| Associated minerals | Quartz, Epidote, Albite, Actinolite, Calcite, Chlorite Group, Prehnite, Smoky Quartz, Adularia, Microcline. |

Clinozoisites

[edit | edit source]

"Epidote and clinozoisite are widely distributed in the andesitic lavas and tufts of the Borrowdale Volcanic Series. Four main types of occurrence may be distinguished, namely quartz-epidote vein fillings; 'Shap type' veins, bordered by pink reaction zones rich in SiO2, Na2O, and K2O; autometasomatized lavas and tufts; and tufts subjected to alkali metasomatism. Epidote alone formed in the quartz-epidote veins; clinozoisite is found with epidote in the other types of occurrence."[13]

Def. a sorosilicate, basic calcium aluminosilicate "mineral found in crystalline schists, a metamorphic product of calcium feldspar"[14] is called a clinozoisite.

Epidotes

[edit | edit source]

Epidote is another usually metamorphic mineral that can occur in volcanic rocks.

Def. any "of a class of mixed calcium iron aluminium sorosilicates found in metamorphic rocks"[15] is called an epidote.

Fencooperites

[edit | edit source]

3O

13 pinwheels cross-connected by Si

8O

22 islands. Credit: Bubenik.{{free media}}

Fersmanites

[edit | edit source]

Harstigites

[edit | edit source]

Harstigite is an extremelly rare sorosilicate (of calcium, manganese and beryllium). Harstigite forms masses colorless to beige in tone. Species presents red fluorescence under SW-UV light.

Leucophanites

[edit | edit source]

Medaites

[edit | edit source]

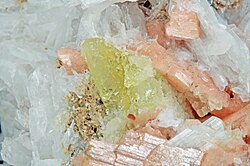

The medaite in the image on the right has sparkling luster and a rose red color, and is from Molinello Mine, Graveglia Valley, Ne, Genova Province, Liguria, Italy.

"Sorosilicate structures with longer clusters ([T

6𝞍19] in medaite, Mn

6[VSi

5O

18(OH)], Gramaccioli et al. 1981) consist of sheets or ribbons of octahedra in which the sorosilicate cluster extends parallel to the sheets or ribbons."[2]

Formula: Mn2+

6V5+

Si

5O

18(OH).[16]

Melilites

[edit | edit source]Rosenhahnites

[edit | edit source]

Rosenhahnite has the formula Ca

3Si

3O

8(OH)

2.

Ruizites

[edit | edit source]

Ruizite has the formula Ca

2Mn

2Si

4O

11(OH)

4·2H

2O.[17]

Ruizite is a sorosilicate mineral discovered at the Christmas mine in Christmas, Arizona, and described in 1977.[17] The mineral is named for discoverer Joe Ana Ruiz.[17]

Ruizite is translucent and orange to red-brown in color with an apricot yellow streak.[18] The mineral occurs as euhedral prisms up to 1 mm (0.039 in) or as radial clusters of acicular (needle-like) crystals.[17]

Ruizite is common at the Christmas mine.[19] The mineral is known from Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Northern Cape Province, South Africa.[18]

Association: Apophyllite, kinoite, junitoite, wollastonite, grossular, diopside, vesuvianite, calcite, chalcopyrite, bornite, sphalerite, smectite (Christmas, Arizona, USA); apophyllite, pectolite, datolite, inesite, orientite, quartz (Wessels mine, South Africa).[17]

Occurrence: In veinlets and on fracture surfaces in metalimestone, formed during cooling of a high-temperature calc-silicate assemblage under oxidizing conditions (Christmas, Arizona, USA).[17] The mineral formed by retrograde metamorphism during cooling of a calc–silicate skarn assemblage in an oxidizing environment.[17][19]

Ruizite crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system and twinning is common along the miller index {100} plane between exactly two crystals.[17] Ruizite's formula was originally identified as CaMn(SiO

3)

2(OH)

2·2H

2O in 1977.[19] The formula was revised to Ca

2Mn3+

2Si

4O

11(OH)

4·2H

2O.[20]

Ruizite's structure consists of edge-sharing Mnφ6 octahedra, connected at corners into sheets and together into a lattice by clusters of Si

4O

11(OH)

2.[21]

Nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, and potassium hydroxide have little effect on ruizite at low temperatures but readily dissolve the mineral at elevated temperatures.[19]

During the investigation of junitoite at the Christmas mine in Christmas, Arizona, Joe Ana Ruiz and Robert Jenkins discovered an unknown brown mineral.[19] Mine geologist Dave Cook located better specimens, and it was determined to be a new mineral species.[19] The mineral was named ruizite in honor of Joe Ruiz as discoverer.[19] Ruizite's properties were analyzed using a sample provided by Joseph Urban, and it was described in the journal Mineralogical Magazine in December 1977.[19] The International Mineralogical Association approved the mineral as IMA 1977-077.[22] Type specimens are housed in the University of Arizona, Harvard University, the National Museum of Natural History, and The Natural History Museum, London.[17]

Tiragalloites

[edit | edit source]

"Tiragalloite belongs to a rare class of compounds with As atoms replacing Si atoms in silicate anions, the so-called arsenosilicates (analoguous to the more common alumosilicates and borosilicates, in which Si atoms are replaced by Al atoms and B atoms, respectively). It contains isolated chains consisting of one (AsO

4) tetrahedron and three (SiO

4) tetrahedra, which are linked by sharing corners. One oxygen atom is protonated, resulting in the anion formula (HAsSi

3O

13)8−

. The tetrahedral sites in the anion are ordered in that the As atoms are only found at the end of the chains, and there is exactly one As atom in each anion."[23]

Tiragalloite is a sorosilicate with an orange, brownish orange color.[23]

"Named after Paolo Onofrio Tiragallo (1905, Carro, La Spezia, Liguria, Italy - 1987), distinguished amateur mineralogist. Conservator and curator of the mineralogical collection of the University of Genoa."[23]

Tiragalloite has the formula Mn2+

4As5+

Si

3O

12(OH).[23]

Common impurities: Ti,Al,V,Fe,Ca,Na,K.[23]

Common associates: areniopleites NaCaMn2+

Mn2+

2(AsO

4)

3 and rhodonites CaMn2+

3Mn2+

[Si

5O

15].[23]

The end member compositions are areniopleites NaCaMn2+

Mn2+

2(AsO

4)

3 and caryinites CaNaCa2+

Mn2+

2As

3O

12.[24]

Vesuvianites

[edit | edit source]

"Minerals such as harkerite, wilkeite, cuspidine, cancrinite, vesuvianite and phlogopite indicate the intrusive melt had a high volatile content which is in agreement with the very high explosivity index of this volcanic district."[25]

Def. a "yellow, green or brown mineral, a mixed calcium, magnesium and aluminium silicate sometimes used as a gemstone"[26] is called a vesuvianite.

Zoisites

[edit | edit source]

On the right is both a rough stone and a cut stone of tanzanite. Tanzanite is the blue/purple variety of the mineral zoisite (a calcium aluminium hydroxy silicate) with the formula (Ca2Al3(SiO4)(Si2O7)O(OH))]. Tanzanite is noted for its remarkably strong trichroism, appearing alternately sapphire blue, violet and burgundy depending on crystal orientation.[27] Tanzanite can also appear differently when viewed under alternate lighting conditions. The blues appear more evident when subjected to fluorescent light and the violet hues can be seen readily when viewed under incandescent illumination. A rough violet sample of tanzanite is third down at left.

Tanzanite in its rough state is usually a reddish brown color. It requires artificial heat treatment to 600 °C in a gemological oven to bring out the blue violet of the stone.[28]

Tanzanite is found only in the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Tanzanite is universally heat treated in a furnace, with a temperature between 550 and 700 degrees Celsius, to produce a range of hues between bluish-violet to violetish-blue. Some stones found close to the surface in the early days of the discovery were gem-quality blue without the need for heat treatment.

Zunyites

[edit | edit source]

5O

16 pentamer of Zunyite. Credit: Bubenik.{{free media}}

Hypotheses

[edit | edit source]- Most minerals on Earth are oxides.

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "sorosilicate". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. June 19, 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 Peter C. Burns and Frank C. Hawthorne (1 January 1993). "Edge-sharing Mn2+

O

4 tetrahedra in the Structure of Akatoreite, Mn2+

9Al

2Si

8O

24(OH)

8". Canadian Mineralogist 31 (1): 321-329. https://rruff.info/doclib/cm/vol31/CM31_321.pdf. Retrieved 26 November 2021. - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Mindat.org - Akatoreite

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Webmineral.com - Akatoreite

- ↑ Handbook of Mineralogy - Akatoreite

- ↑ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA-CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine 85: 291-320. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/mineralogical-magazine/article/imacnmnc-approved-mineral-symbols/62311F45ED37831D78603C6E6B25EE0A.

- ↑ Dollase, W. A. (1971). "Refinement of the crystal structure of epidote, allanite, and hancockite". American Mineralogist 56: 447–464. http://rruff.info/uploads/AM56_447.pdf.

- ↑ Catlos, E. J.; Sorensen, S. S.; Harrison, T. M. (2000). "Th-Pb ion-microprobe dating of allanite". American Mineralogist 85: 633–648. http://sims.ess.ucla.edu/PDF/catlos_et_al_AMMIN_2000.pdf.

- ↑ Klein, C., Dutrow, B. (2007) Manual of Mineral Science. Wiley Publishers, p. 500.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Allanite-(Ce). Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Allanite

- ↑ Handbook of Mineralogy: Magnesioaxinite

- ↑ R. G. J. Strens (June 1964). "Epidotes o.f the Borrowdale Volcanic rocks of central Borrowdale". Mineralogical Magazine 33 (265): 868-86. doi:10.1180/minmag.1964.033.265.04. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.606.5931&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- ↑ Pinkfud (1 November 2004). "clinozoisite". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ SemperBlotto (23 March 2006). "epidote". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Medaite

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W. et al., eds. Ruizite, In: Handbook of Mineralogy. Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. http://www.handbookofmineralogy.org/pdfs/ruizite.pdf.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Ruizite". Mindat. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 Williams, Sidney A.; Duggan, M. (December 1977). "Ruizite, A New Silicate Mineral from Christmas, Arizona". Mineralogical Magazine 41 (320): 429–432. doi:10.1180/minmag.1977.041.320.01. http://www.minersoc.org/pages/Archive-MM/Volume_41/41-320-429.pdf.

- ↑ Dunn, Pete J. (March–April 1985). "New Mineral Names, New Data". American Mineralogist 70 (3–4): 441. http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM70/AM70_436.pdf.

- ↑ Hawthorne, F. C. (1984). "The crystal structure of ruizite, a sorosilicate with an [Si4Ø13] cluster". Tschermaks mineralogische und petrographische Mitteilungen 33 (2): 135–146. doi:10.1007/BF01083069.

- ↑ "The New IMA List of Minerals – A Work in Progress – Update: November 2012" (PDF). Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification. International Mineralogical Association. p. 146. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Tiragalloite

- ↑ Kimberly T. Tait and Frank C. Hawthorne (1 January 2003). "Refinement of the Crystal Structure of Arseniopleite: Confirmation of its Status as a Valid Speices". The Canadian Mineralogist 41 (1): 71-77. https://rruff.info/doclib/cm/vol41/CM41_71.pdf. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ↑ G. Cavarretta; F. Tecce (1987). "Contact metasomatic and hydrothermal minerals in the SH2 deep well, Sabatini volcanic district, Latium, Italy". Geothermics 16 (2): 127-45. doi:10.1016/0375-6505(87)90061-7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0375650587900617. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (17 December 2006). "vesuvianite, In: Wiktionary". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ E. Skalwold. Pleochroism: trichroism and dichroism in gems. Nordskip.com. http://www.nordskip.com/pleochroism.html. Retrieved 2011-08-29.

- ↑ YourGemologist / International School of Gemology Study of Heat Treatment. Yourgemologist.com. http://www.yourgemologist.com/heattreatment.html. Retrieved 2011-08-29.