Art

Art is a diverse range of human activities and the products of those activities.[1][2]

Art can be visual, auditory, and more. Auditory art is called music. Visual arts encompass fields such as traditional visual arts, sculptural arts, digital renderings (2d and 3d), digital design and game design. Also included in this field is theatre or performing arts, textile arts, culinary arts, and architecture. Art can be considered the decoration of each sense in order to enrich the human experience.

Humanities

[edit | edit source]"The purpose of incorporating humanities teaching into medical education is to encourage students to develop into more sensitive and caring doctors who communicate well with their patients and colleagues."[3]

Colors

[edit | edit source]

It "is possible for a painter to generate all colors by mixing together different ratios of three suitably chosen primaries, but, in fact, most painters use a wide range of paint colors."[4]

The name Pomo[, or Pomo people,] ... originally meant "those who live at red earth hole" and was once the name of a village in southern Potter Valley near the present-day community of Pomo.[5] It may have referred to local deposits of the red mineral magnesite, used for red beads, or to the reddish earth and clay such as hematite mined in the area.[6]

Cosmetic body art may be the earliest form of ritual in human culture, dating over 100,000 years ago from the African Middle Stone Age in the form of utilised red mineral pigments (red ochre) including crayons associated with the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa.[7][8][9][10]

A variant of ochre containing a large amount of hematite, or dehydrated iron oxide, has a reddish tint known as red ochre.[11] It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced by this pigment, especially a light brownish-yellow.[12][13]

Minerals

[edit | edit source]"Small catalogues of reference Raman spectra of interest for analysing geomaterials or biomaterials of relevance to art history or archaeology are gradually being published by different research groups."[14]

Art theory

[edit | edit source]Def. the conscious production or arrangement of sounds, colours, forms, movements, or other elements in a manner that affects the sense of beauty, specifically the production of the beautiful in a graphic or plastic medium is called art.

Senses

[edit | edit source]Many art forms involve more than one sense.

"The theme of the Five Senses made its first appearance in the Early Middle Ages.1 From the outset, with the extraordinary Fuller broach in the British Museum, which dates from the ninth century, its monuments practically all belong to secular imagery.2 There are scattered instances in Romanesque art, but only from the thirteenth century on do the Senses become more frequently depicted."[15]

Audio

[edit | edit source]![]() Audio (US) (help·info), audio expression of the English pronunciation of the word skill.

Audio (US) (help·info), audio expression of the English pronunciation of the word skill.

"Besides technological developments, the evolution of digital sound and music was shaped by a multitude of earlier musical experiments that pointed to the possibilities of the new medium."[16]

Learning resources

[edit | edit source]Gustatory

[edit | edit source]

Although the image at right is of a plate of food specific to Ardennes, France, when the food is eaten, it may be considered pleasing.

Kinesthetic

[edit | edit source]Def.

- the perception of the movement of one's own body, its limbs and muscles etc,

- a spectator's perception of the motion of a performer, or, the effect of the motion of a scene on the spectator,

- the perception of the position and posture of the body; also, more broadly, including the motion of the body as well

is called kinesthesia.

Usage notes:

- The traditional rules of pronunciation of Greco-Latin vocabulary prefer the I in the first syllable to be long. The more common pronunciation with short I is by analogy with other words from this root such as kinetic and kinesiology where short I is expected.[17]

- The etymological meaning of the word as used in physiology refers specifically to the motion of the body, and a distinction between kinesthesia and the sense of the position of the body is sometimes made in technical texts. In popular use the distinction is made less often.[18]

Nocerals

[edit | edit source]

Nose warmers are a thermal noceral.

Olfactory

[edit | edit source]Def. the sense of smell is called olfactory.

Tactile

[edit | edit source]

As an example of tactile art there is the tactile paving at right shown in the photograph.

Functionally, the paving helps blind individuals locate the platform end. Is this only functional paving or is it also tactile art, especially to those who are blind and perceive it?

Thermals

[edit | edit source]

Def. a "heavy, loosely woven fabric, usually large and woollen, used for warmth while sleeping or resting"[19] is called a blanket.

The blanket on the left is a Navajo woman's fancy manta, wool, ca. 1850-1865, worn as a blanket or a wrap-around dress.[20]

Vestibular

[edit | edit source]Def. of or relating to the vestibule of the inner ear, the vestibular system, the vestibular nerve, or the vestibular sense (vestibular impulses) is called vestibular.

The art that pertains to hearing aesthetics is vestibular art.

Visuals

[edit | edit source]

The visual arts include the creation of images or objects in fields like painting, sculpture, printmaking, and photography.

Beauty

[edit | edit source]Def. the property, quality or state of being "that which pleases merely by being perceived" (Aquinas) is called beauty.

Skills

[edit | edit source]Def. a capacity to do something well is called a skill.

Mediums

[edit | edit source]An artistic medium is the substance or material on which or from which the artistic work is made.

Forms

[edit | edit source]An art form is the specific shape, or quality of an artistic expression, where the media used often influence the form.

Genre

[edit | edit source]A genre consists of conventions and styles for a particular medium.

Style

[edit | edit source]The style is a way of painting, writing, composing, building, etc., characteristic of a particular period, place, person, or movement.

Aesthetics

[edit | edit source]Def. the branch of philosophy that deals with the principles of beauty and artistic taste is called aesthetics.

Chemistry

[edit | edit source]"The botanical sources and chemical compositions [...] of natural resins [are] used, [or] likely to have been used, in the fabrication of objects of art and archaeology. They fall into two main chemical groups: those containing diterpenoids—from the order Coniferales and from the Leguminosae family—and those containing triterpenoids from several families of broad-leaved trees."[21]

20th Century

[edit | edit source]

Bottle, Tswa peoples, Rwanda, Early-mid 20th century, Ceramic, resin, commercial paint, wax: Potters--primarily women--hand-build a variety of vessels that they embellish with beautiful colors, designs and motifs before firing them at low temperatures. Containers made for daily use hold water or serve as cooking utensils. They also make vessels to be used in special ceremonies or that become part of an assemblage of objects placed in a shrine. The brilliant red, bold zigzag motif was probably rendered with imported paint and applied to the body after firing. The surface was covered with wax to enhance the natural color of the clay. The paint and wax may have been applied to the bottle by someone other than the potter.

19th Century

[edit | edit source]

"This blanket [in the image on the left] was woven at the end of the "wearing blanket era," just as the railroad came into the Southwest in 1881. The heavier handspun yarns and synthetic dyes are typical of pieces made during the transition from blanket weaving to rug weaving."-Ann Hedlund, Arizona State Museum.

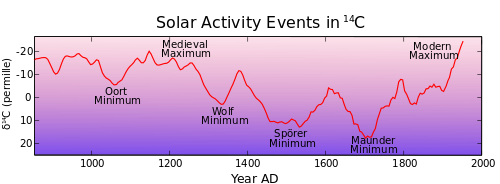

Little Ice Age

[edit | edit source]

The Little Ice Age (LIA) appears to have lasted from about 1218 (782 b2k) to about 1878 (122 b2k).

The first painting on the left dates from 1673.

The image on the right hangs in the interior of the ayuntamiento of San Cristobal de La Laguna, Tenerife.

The painting on the right shows the surrender of the Guanches kings of Tenerife to Ferdinand and Isabella. This appears to have occurred c. 504 b2k.

The painting on the left was painted in 1764. It depicts the surrender of the Guanches leaders Bencomo mencey with Tacoronte, Anaga and Tegueste to Governor Alonso Fernández de Lugo with his captains and noble friends, by bringing gifts to the governor in 1496.

High Middle Ages

[edit | edit source]

Medieval Warm Period

[edit | edit source]

The High Middle Ages date from around 1,000 b2k to 700 b2k.The Medieval Warm Period (MWP) dates from around 1150 to 750 b2k.

Classical history

[edit | edit source]

The classical history period dates from around 2,000 to 1,000 b2k.

On the right are "pre-Columbian wall paintings which can be found in the Temple of the Warriors, Chichen Itza, on the east coast of Mexico. The first [on the right] depicts prisoners after their capture by the dark-skinned natives, and the second [down on the right], shows a man with long blond hair being sacrificed."[22]

The map on the left shows the current geographical locations of anthropological remains from various northeastern populations of OK, Okhotsk; UL, Ulichi; NV, Nivkhi; NG, Negidal; AI, Ainu; HJ, Hokkaido Jomon; JP, Mainland Japanese; CN, Chinese; KR, Korean; UD, Udegey; KY, Koryak; IT, Itelmen; ES, Eskimo; CH, Chukuchi; EV, Evenki; BR, Buryat; TF, Tofalar; TV, Tuvan; TB, Tubalar; NS, Nganasan; KT, Ket; MN, Mansi.

"The Okhotsk culture developed around the southern coastal regions of the Okhotsk Sea during the 5th–13th centuries (Amano, 2003a)."[23]

"The Okhotsk culture differs in certain respects from the Epi-Jomon culture (3rd century BC–7th century AD) and the Satsumon culture (8th–14th centuries: Amano, 2003b), which were contemporary with the Okhotsk culture and developed in the southern and inner parts of Hokkaido Island."[23]

The "Okhotsk people [may have] merged with the Satsumon people (a direct ancestoral lineage of the Ainu people) on Hokkaido, resulting in the establishment of the Ainu people (Utagawa, 2002)."[23]

The "Okhotsk people were closely related to the Ulchi, Ainu, and Negidal."[23]

The "Koryak are closely related to the Okhotsk people [...]."[23]

The Mosque of Uqba (Great Mosque of Kairouan) in Tunisia is one of the finest, most significant and best preserved artistic and architectural examples of early great mosques. Dated in its present state from the 9th century, it is the ancestor and model of all the mosques in the western Islamic lands.[24]

Subatlantic history

[edit | edit source]

The "calibration of radiocarbon dates at approximately 2500-2450 BP [2500-2450 b2k] is problematic due to a "plateau" (known as the "Hallstatt-plateau") in the calibration curve [...] A decrease in solar activity caused an increase in production of 14C, and thus a sharp rise in Δ 14C, beginning at approximately 850 cal (calendar years) BC [...] Between approximately 760 and 420 cal BC (corresponding to 2500-2425 BP [2500-2425 b2k]), the concentration of 14C returned to "normal" values."[25]

The petroglyphs in the image on the right have not been dated, but could be from the subatlantic period.

A more varied set of petroglyphs in the second image on the right is in the Cave of Belmaco. The entrance to which is shown on the left.

"There are drawings of Jomonese types even from Korea that show them as very robust types that do look quite Ainuid. It’s now known that the Ainu are a cold-adapted Australoid type by skulls, although their genes look Japanese and Korean. There has long been thought to be an Austronesian-like layer in Japanese which would logically go back to the ancient language spoken by these immigrants from Thailand. In other words, quite a few of the Japanese came up from the far south from SE Asia long ago. These earlier people mixed by Yayoi from Korea who invaded 2,300 YBP and slowly conquered the Ainu up the peninsula to the Far North. This conquest was apparently still underway in the modern era. The Japanese gene pool is ~20% Ainu."[26]

Subboreal history

[edit | edit source]The "period around 850-760 BC [2850-2760 b2k], characterised by a decrease in solar activity and a sharp increase of Δ 14C [...] the local vegetation succession, in relation to the changes in atmospheric radiocarbon content, shows additional evidence for solar forcing of climate change at the Subboreal - Subatlantic transition."[25]

The "Holocene climatic optimum in this interior part of Asia [Lake Baikal] corresponds to the Subboreal period 2.5–4.5 ka".[27]

Although the spirals in the image on the right are undated, they may have been made as early as the Subboreal. These spirals on the Canary Islands are similar to ones found in Galicia, which is north of Portugal.

Early history

[edit | edit source]

The early history period dates from around 3,000 to 2,000 b2k.

The Guanches are believed to be the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands perhaps as early as 3,000 b2k.

The first image on the right shows examples of Guanches pottery.

The second image down on the right is one of the Pyramids of Guimar, Canary Islands.

The "Guanches built several small step pyramids on the islands, using the same model as those found in ancient Egypt and in Mesopotamia."[22]

"The pyramids have an east-west alignment which also indicates that they probably had a religious [or astronomical] purpose, associated with the rise and setting of the sun."[22]

"Carefully built stairways on the west side of each pyramid lead up to the summit, which in each case has a flat platform covered with gravel, possibly used for religious or ceremonial purposes."[22]

They "shared a number of cultural characteristics with the ancient Egyptians and [...] their building style appears to have been replicated in South and Central America."[22]

The mummies on the left have red hair, the third down has blonde, and other Nordic features of the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands.

"An examination of one of the mummies' bodies showed incisions that virtually matched those found in Egyptian mummies, although the string used by the Guanche embalmers to close the wounds was much coarser than would have been used by the Egyptian experts."[22]

"Like the Celtic Tocharians, the finest evidence of what the original Guanche looked like, is in the fortuitous existence of original Guanche mummies, which are on public display in that island group's national museum."[22]

"As the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands were fair-haired and bearded, it was possible [...] that long before the 15th Century, people of the same stock as those who settled the Canary Islands, also sailed the same route along the Canary Current that took Christopher Columbus to the Americas."[28]

"According to the Aztec and Olmec (Central American Amerind) legends, their god, Quetzalcoatl, had Nordic features (eyes and hair color) and a beard. This god came from over the sea and taught the Amerinds how to raise corn and build structures."[22]

"The existence of the red-haired Guanches on the Canary Islands, combined with the red-haired pre-Columbus mummies found in South America and the marked similarity in pyramid building styles, indicate that an over the atlantic people probably used the Canaries Current to cross the Atlantic, most likely between 2000 and 500 BC."[22]

"The original occupants of the Canary Islands were a native people called the Guanche. Their mummies have been found with red hair and blond hair. Reportedly, the men were around 7 feet and the women around 6 feet."[29]

"Generally dolichocephalic, fair-featured with blond or red-hair, with males over six foot tall and women approaching six feet in height, they were a people of tall, strong and comely appearance, resembling many Northern Europeans today but for a generally greater and more robust stature. Their general appearance and racial characteristic were valued by the Spanish: "All historians agree in reporting that the Canarians were beautiful. They were tall, well built and of singular proportion. They were also robust and courageous with high mental capacity. Women were very beautiful and Spanish Gentlemen often used to take their wives among the population.""[30]

The third image down on the right is a statue made by an unknown Guanches, as is the fourth image down on the right. It is apparently of an entity called Guatimac.

In the image on the lowest right are Guanches engravings in a rock cave on La Palma island of the Canary Islands.

Iron Age

[edit | edit source]

The iron age history period began between 3,200 and 2,100 b2k.

At about 3,000 b2k, as shown in the map image second down on the left, Libya was the Cyrene peninsula.

Bronze Age

[edit | edit source]A general world-wide use of bronze occurred between 5300 and 2600 b2k.

"The earliest known iron artefacts are nine small beads securely dated to circa 3200 BC, from two burials in Gerzeh, northern Egypt."[31]

"Since both tombs are securely dated to Naqada IIC–IIIA, c 3400–3100 BC (Adams, 1990: 25; Stevenson, 2009: 11–31), the beads predate the emergence of iron smelting by nearly 2000 years, and other known meteoritic iron artefacts by 500 years or more (Yalçın 1999), giving them an exceptional position in the history of metal use."[31]

The image on the left uses neutron radiography to show the metal underneath the corrosion.

"Bead UC10738 [in the image on the right] has a maximum length of 1.5 cm and a maximum diameter of 1.3 cm, bead UC10739 is 1.7 cm by 0.7 cm, and bead UC10740 is 1.7 cm by 0.3 cm. All three beads are of rust-brown colour with a rough surface, indicative of heavy iron corrosion. Initial analysis by [proton–induced X–ray fluorescence] pXRF indicated an elevated nickel content of the surface of the beads, in the order of a few per cent, and their magnetic property suggested that iron metal may be present in their body (Jambon, 2010)."[31]

Atlantic history

[edit | edit source]

The "Atlantic period [is] 4.6–6 ka [4,600-6,000 b2k]."[27]

The petroglyph on the right contains spirals way over to the right in the image. This petroglyph is IV-II millemium BCE and shows a cup-and-ring mark and deer hunting scenes.

These petroglyphs from Galicia look like the petroglyphs from the Canary Islands shown on the left.

Copper Age

[edit | edit source]

The copper age history period began from 6990 b2k.

The "oldest securely dated evidence of copper making, from 7,000 years ago [6990 b2k], at the archaeological site of Belovode, Serbia."[32]

The "Scandinavian one 2000 years earlier [8,000 b2k]."[33]

The Neolithic Subpluvial may have begun during the 7th millennium BC and was strong for about 2,000 years; it waned over time and ended after the 5.9 kiloyear event (3900 BCE) [5900 b2k].[34]

At the right is an image of an engraving of an elephant at Wadi Mathendous in southwest Libya. This engraving may date from the Neolithic Subpluvial.

Giraffes are shown in the engraving on the left.

The spear point or arrow point at the lower right from Algeria needs more descriptive information.

The image at the lower left shows petroglyphs of animals, including a crocodile, on rocks from Wadi Mathendous near Germa, Fezzan, southwestern Libya.

The lowest image on the left shows cave art exhibited at the Germa Museum, possibly from Wadi Mathendous.

Pre-Boreal transition

[edit | edit source]

The last glaciation appears to have a gradual decline ending about 12,000 b2k. This may have been the end of the Pre-Boreal transition.

"About 9000 years ago the temperature in Greenland culminated at 4°C warmer than today. Since then it has become slowly cooler with only one dramatic change of climate. This happened 8250 years ago [...]. In an otherwise warm period the temperature fell 7°C within a decade, and it took 300 years to re-establish the warm climate. This event has also been demonstrated in European wooden ring series and in European bogs."[33]

"The Pre-boreal period marks the transition from the cold climate of the Late-glacial to the warmer climate of Post-glacial time. This change is immediately obvious in the field from the nature of the sediments, changing as they do from clays to organic lake muds, showing that at this time a more or less continuous vegetation cover was developing."[35]

"At the beginning of the Pre-boreal the pollen curves of the herbaceous species have high values, and most of the genera associated with the Late-glacial fiora are still present e.g. Artemisia, Polemomium and Thalictrum. These plants become less abundant throughout the Pre-boreal, and before the beginning of the Boreal their curves have reached low values."[35]

Archaeological evidence suggests that the coastal plain of ancient Libya was inhabited by Neolithic peoples from as early as 8000 BC, 10,000 b2k.

Rock paintings and carvings that occur at Wadi Mathendous and in the mountainous region of Jebel Acacus reveal that the Libyan Sahara contained rivers, grassy plateaus and an abundance of wildlife such as giraffes, elephants and crocodiles.[36]

"Fossilized bones show that by the sixth millennium B.C. (or about 7,000 years ago), cattle, sheep and goats roamed over green savanna, and rock art [at left] depicts cows with full udders. The occasional image even shows milking".[37]

Populations of pastoralists such as Iberomaurusian[38][39] have left paintings that date back to at least 10,000 BCE, 12,000 b2k, in Northern Niger and neighboring parts of Algeria and Libya.

Heinrich event H1

[edit | edit source]

This stadial starts about 17.5 ka, extends to about 15.5 ka and is followed after a brief warming by H1.

Laugerie Interstadial

[edit | edit source]

The weak interstadial corresponding to GIS 2 occurred about 23.2 kyr B.P.[40]

"GIS 2 (start) 21.556 [to] GIS 2 (end) 21.407 ka BP".[41]

Heinrich Event 2 (H2) extends "22-25.62 ka BP".[41]

The δ18O values from GISP-2 follow the diagram of Wolfgang Weißmüller. The positions of the Dansgaard-Oeschger events DO1 to DO4 and the Heinrich events H1 to H3 are also indicated. DV 3-4 and DV 6-7 are cold events marked by ice wedges in the upper loess of Dolní Veštonice.

Hasselo stadial

[edit | edit source]The "Hasselo stadial [is] at approximately 40-38,500 14C years B.P. (Van Huissteden, 1990)."[42]

The "Hasselo Stadial [is a glacial advance] (44–39 ka ago)".[43]

"Around 39,000 years ago, a Neanderthal huddled in the back of a seaside cave at Gibraltar, safe from the hyenas, lions and leopards that might have prowled outside. Under the flickering light of a campfire, he or she used a stone tool to carefully etch what looks like a grid or a hashtag [in the image at the right] onto a natural platform of bedrock."[44]

"This was intentional — this was not somebody doodling or scratching on the surface."[45]

"Neanderthals might have behaved more like Homo sapiens than previously thought: They buried their dead, they used pigments and feathers to decorate their bodies, and they may have even organized their caves."[44]

"Art is something else — it's an indication of abstract thinking."[45]

"In Gorham's Cave, Finlayson and colleagues were surprised to find a series of deeply incised parallel and crisscrossing lines when they wiped away the dirt covering a bedrock surface. The rock had been sealed under a layer of soil that was littered with Mousterian stone tools (a style long linked to Neanderthals). Radiocarbon dating indicated that this soil layer was between 38,500 and 30,500 years old, suggesting the rock art buried underneath was created sometime before then."[44]

"Gibraltar is one of the most famous sites of Neanderthal occupation. At Gorham's Cave and its surrounding caverns, archaeologists have found evidence that Neanderthals butchered seals, roasted pigeons and plucked feathers off birds of prey. In other parts of Europe, Neanderthals lived alongside humans — and may have even interbred with them. But 40,000 years ago, the southern Iberian Peninsula was a Neanderthal stronghold."[44]

"Modern humans had not spread into the area yet."[45]

"More than 50 stone-tool incisions were needed to mimic the deepest line of the grid, and between 188 and 317 total strokes were probably needed to create the entire pattern."[44]

"It's very basic. It's very simple. It's not a Venus. It's not a bison. It's not a horse."[46]

"There is a huge difference between making three lines that any 3-year-old kid would be able to make and sculpting a Venus."[46]

"My own feeling is that if Neanderthals regularly used symbols, and given their longtime occupation throughout large parts of the Old World, we probably would have found clearer evidence by now."[47]

Scientists need "more than a few scratches — deliberate or not — to identify symbolic behavior on the part of Neanderthals."[47]

"Symbols, by definition, have meanings that are shared by a group of people, and because of that, they are often repeated. By itself, this is a unique example and without any intrinsic meaning … the question is not 'Could it be symbolic?' but rather 'Was it symbolic?' And to demonstrate that, it would be very important to have repeated examples."[47]

Neanderthals had an average brain size of 1500 cm3.[48] Another source puts brain sizes from three localities as Spy I 1,305 ml, Spy II 1,553 ml, and Djebel Ihroud I 1305 ml.[49]

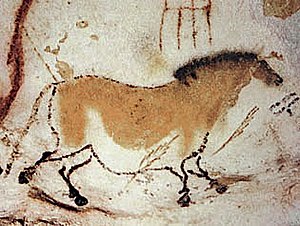

Sculptures, cave paintings, rock paintings and petroglyphs from the Upper Paleolithic date to roughly 40,000 years ago.

"New dating of cave paintings [a portion is shown on the left] in Indonesia reveals that they are more than 40,000 years old, casting doubt on theories of art in human prehistory. These paintings are among the earliest ever found, and their location is a surprise to archaeologists. Other contemporary cave art has been found only in Europe, and archaeologists thought that the practice of cave painting originated there. The revised age measurements, combined with previous findings that some carved patterns in Africa are 50,000 years old, suggest that humans may have developed artistic proclivities before their migration out of Africa, beginning around 75,000 years ago."[50]

Wisconsinian glacial

[edit | edit source]Wisconsinian glacial began at 80,000 yr BP.[51]

The oldest art objects in the world—a series of tiny, drilled snail shells about 75,000 years old—were discovered in a South African cave.[52]

Brørup interstadial

[edit | edit source]The "Brørup interstade [is about] 100 ka BP".[53] It corresponds to GIS 23/24.[40]

MIS Boundary 5.4 (peak) is at 109 ka.[54]

Containers that may have been used to hold paints have been found dating as far back as 100,000 years.[55]

Yarmouthian interglacial

[edit | edit source]"Clay deposition in the Piauí River floodplain around 436 ± 51.5 ka occurred during a warmer period of the [Yarmouthian interglaciation] Aftonian interglaciation, corresponding to isotope stage 12 (Ericson and Wollin, 1968)."[56]

"The extinctions and earliest known first occurrences of the 26 extant and 8 extinct cyst taxa in the three samples (with a minimum 430,000 yr BP Yarmouthian age) corroborate a likely assemblages with a maximum age of Illinoian (ca. 220,000-430,000 yr BP) in Unit I."[51]

Yarmouthian spans 420,000-500,000 yr BP.[51]

A "fossil freshwater shell assemblage from the Hauptknochenschicht (‘main bone layer’) of Trinil (Java, Indonesia), the type locality of Homo erectus discovered by Eugène Dubois in 1891 (refs 2 and 3) [in] the Dubois collection (in the Naturalis museum, Leiden, The Netherlands) [there is evidence] for freshwater shellfish consumption by hominins, one unambiguous shell tool, and a shell with a geometric engraving. We dated sediment contained in the shells with 40Ar/39Ar and luminescence dating methods, obtaining a maximum age of 0.54 ± 0.10 million years and a minimum age of 0.43 ± 0.05 million years."[57]

Paleolithic

[edit | edit source]

The paleolithic period dates from around 2.6 x 106 b2k to the end of the Pleistocene around 12,000 b2k.

Because of fossil and tool discoveries, there is proof that some representatives of Homo erectus for the first time about 2 million years ago ... over Northwest Africa south of Spain.[58]

Around 600,000 years ago, there was probably a second wave [of Homo erectus].[59]

About 200,000 years ago, early or archaic anatomically modern humans [evolved] from Homo erectus.[60]

It was the Sahara, in contrast to the coastal strip and oases, was only habitable when sufficient rainfall would allow sufficient flora and fauna.[61]

In the image at the right are apparent stone tools from the current sandy deserts of North Africa. On the left is a worked stone of 440 mm in length that comes from Libyan Erg Tamiset (latitude N25.25, longitude E10.52). On the right is a worked stone of 345 mm in length from Erg Murzuq in the Libyan southwest (N24.29/E11.59). The middle worked stone of 360 mm is a hand ax native to south Algeria, from the Erg Tiffemine (N26.29)/E06.49).

Hypotheses

[edit | edit source]- Art can be free of a dominant group.

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Art: definition. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/art.

- ↑ art. Merriam-Websters Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/art.

- ↑ Ruric Anderson; David Schiedermayer (2003). "The Art of Medicine through the Humanities: an overview of a one‐month humanities elective for fourth year students". Medical Education 37 (6): 560-2. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01538.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01538.x/full. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ Margaret Livingstone (2002). DH Hubel. ed. Vision and Art - The Biology of Seeing. GoogleDrive. https://www.googledrive.com/host/0B4QDaAzM9KaiTkRPc2pBSFhxUm8/Biology/019receptors/Further%20reading/Vision%20Article.pdf. Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- ↑ Alfred L. Kroeber (1916). "California place names of Indian origin". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 12 (2): 31–69. http://soda.sou.edu/awdata/030731c1.pdf..

- ↑ McClendon and Oswalt 1978:277.

- ↑ Power, C. 2010. Cosmetics, identity and consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 17, 7-8: 73-94.

- ↑ Power, C. 2004. Women in prehistoric art. In G. Berghaus (ed.), New Perspectives in Prehistoric Art. Westport, CT & London: Praeger, pp. 75-104.

- ↑ Watts, Ian. 2009. Red ochre, body painting and language: in-terpreting the Blombos ochre. In The Cradle of Language, Rudolf Botha and Chris Knight (eds.), pp. 62–92. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Watts, Ian. 2010. The pigments from Pinnacle Point Cave 13B, Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution 59: 392–411.

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary. 1969.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (2002), Oxford University Press.

- ↑ The Random House College Dictionary, Revised Edition, (1980). "Any of a class of natural earths, mixtures of hydrated oxides of iron and various earthy materials, ranging in colour from pale yellow to orange and red, and used as pigments. A colour ranging from pale yellow to reddish-yellow."

- ↑ M. Bouchard; D.C. Smith (August 2003). "Catalogue of 45 reference Raman spectra of minerals concerning research in art history or archaeology, especially on corroded metals and coloured glass". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 59 (10): 2247-66. doi:10.1016/S1386-1425(03)00069-6. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386142503000696. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ Carl Nordenfalk (1985). "The Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauid Institutes 48: 1-22. http://storage.ugal.com/3871/nordenfalk---the-five-senses2.pdf. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ Christiane Paul (2003). Thames. ed. Digital Art, In: world of art. Flong.com. pp. 132-6. http://www.flong.com/storage/pdf/press/2003_paul_digitalart.pdf. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ John Sargeaunt, The Pronunciation of English Words Derived from the Latin, 1920. [1]

- ↑ Terence R. Anthoney, Neuroanatomy and the Neurologic Exam: A Thesaurus of Synonyms, Similar-Sounding Non-Synonyms, and Terms of Variable Meaning, 1993. ISBN 0849386314 [2]

- ↑ Equinox (9 September 2013). blanket. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/blanket. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ↑ John S. Mills; Raymond White (February 1977). "Natural Resins of Art and Archaeology Their Sources, Chemistry, and Identification". Science and Technology of Archaeological Research 22 (1): 12-31. http://www.maneyonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/sic.1977.003. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 History of White Race - Chapter 6 (2008). "To The Ends Of The Earth - Lost White Migrations". The Guanches of the Canary Islands. Bibliotecapleyades. http://www.white-history.com/hwr6a.htm. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Takehiro Sato; Tetsuya Amano; Hiroko Ono; Hajime Ishida; Haruto Kodera; Hirofumi Matsumura; Minoru Yoneda; Ryuichi Masuda (2009). "Mitochondrial DNA haplogrouping of the Okhotsk people based on analysis of ancient DNA: an intermediate of gene flow from the continental Sakhalin people to the Ainu". Anthropological Science 117 (3): 171-80. doi:10.1537/ase.081202. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ase/117/3/117_081202/_article. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ John Stothoff Badeau; John Richard Hayes. The Genius of Arab civilization: source of Renaissance. Taylor & Francis 1983. pp. 104. https://books.google.com/books?id=IaM9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA104&cd=3#v=onepage&f=false.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 A. Speranza; J. van der Plicht; B. van Geel (November 2000). "Improving the time control of the Subboreal/Subatlantic transition in a Czech peat sequence by 14C wiggle-matching". Quaternary Science Reviews 19 (16): 1589-1604. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00108-0. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/30494985_Improving_the_time_control_of_the_SubborealSubatlantic_transition_in_a_Czech_peat_sequence_by_14C_wiggle-matching/file/60b7d51c350cf2efa0.pdf. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

- ↑ Robert Lindsay (1 April 2017). An Ancient Link Between India and Australia. WordPress. https://robertlindsay.wordpress.com/category/raceethnicity/asians/northeast-asians/ainu/. Retrieved 2017-05-29.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 E.B. Karabanov; A.A. Prokopenko; D.F. Williams; G.K. Khursevich (March 2000). "A new record of Holocene climate change from the bottom sediments of Lake Baikal". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 156 (3-4): 211–24. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(99)00141-8. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031018299001418. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

- ↑ Thor Heyerdahl (2008). "To The Ends Of The Earth - Lost White Migrations". The Guanches of the Canary Islands. Bibliotecapleyades. http://www.white-history.com/hwr6a.htm. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Sharon Day (18 March 2014). Canary Islands: Oddities and Coincidences?. Ghost Hunting Theories. http://www.ghosthuntingtheories.com/2014/03/canary-islands-oddities-and-coincidences.html. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Burlington News (18 March 2014). Red Haired Mummies Canary Islands. Ghost Hunting Theories. http://www.burlingtonnews.net/redhairedmummiescanaryislands.html%5C. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Thilo Rehrena; Tamás Belgya; Albert Jambon; György Káli; Zsolt Kasztovszky; Zoltán Kis; Imre Kovács; Boglárka Maróti et al. (December 2013). "5,000 years old Egyptian iron beads made from hammered meteoritic iron". Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (12): 4785–92. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.002. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440313002057. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ↑ Miljana Radivojevic; Thilo Rehren (23 September 2010). Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers. London England: UCL Institute of Archaeology. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/calendar/articles/20100924. Retrieved 2015-01-18.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Willi Dansgaard (2005). The Department of Geophysics of The Niels Bohr Institute for Astronomy Physics and Geophysics at The University of Copenhagen Denmark. ed. Frozen Annals Greenland Ice Cap Research. Copenhagen, Denmark: Niels Bohr Institute. pp. 123. ISBN 87-990078-0-0. http://www.iceandclimate.nbi.ku.dk/publications/FrozenAnnals.pdf/. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Sources differ on specific date ranges, which necessarily varied over such a wide geographic expanse. One (Bard, Kathryn A. (1999), ed. Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London, Routledge, pg 863) gives "9000–5000 BP," or 7000–3000 BCE, for the duration of the subpluvial. Another (Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt. London, Routledge, pg 372) places the end of the subpluvial c. 3300 BCE.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 J. W. Franks; W. Pennington (April 1961). "The Late-Glacial and Post-Glacial Deposits of the Esthwaite Basin, North Lancashire". New Phytologist 60 (1): 27-42. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1961.tb06237.x/asset/j.1469-8137.1961.tb06237.x.pdf;jsessionid=EB6966DF0A2FBCC3534CCD6A6413808D.f02t01?v=1&t=i23es9k1&s=e619673cf5bc8be51450a303a914df03f8cba94d. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

- ↑ Roland Oliver (1999), The African Experience: From Olduvai Gorge to the 21st Century (Series: History of Civilization), London: Phoenix Press, revised edition, pg 39.

- ↑ Stephanie Pappas (June 20, 2012). Got milk? Research finds evidence of dairy farming 7,000 years ago in Sahara.. The Christian Science Monitor. http://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2012/0620/Got-milk-Research-finds-evidence-of-dairy-farming-7-000-years-ago-in-Sahara. Retrieved 2012-06-25.

- ↑ Kefi R; Bouzaid E; Stevanovitch A; Beraud-Colomb E. MITOCHONDRIAL DNA AND PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF PREHISTORIC NORTH AFRICAN POPULATIONS. ISABS. https://web.archive.org/web/20160311200852/http://www.isabs.hr/PDF/2013/ISABS-2013_book_of_abstracts.pdf. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Bernard Secher; Rosa Fregel; José M Larruga; Vicente M Cabrera; Phillip Endicott; José J Pestano; Ana M González. The history of the North African mitochondrial DNA haplogroup U6 gene flow into the African, Eurasian and American continents. BMC Evolutionary Biology. http://bmcevolbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2148-14-109. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Barbara Wohlfarth (April 2010). "Ice-free conditions in Sweden during Marine Oxygen Isotope Stage 3?". Boreas 39: 377-98. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.2009.00137.x. http://people.su.se/~wohlf/pdf/Wohlfarth%20Boreas%202010.pdf. Retrieved 2014-11-06.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Sasha Naomi Bharier Leigh (2007). A STUDY OF THE DYNAMICS OF THE BRITISH ICE SHEET DURING MARINE ISOTOPE STAGES 2 AND 3, FOCUSING ON HEINRICH EVENTS 2 AND 4 AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO THE NORTH ATLANTIC GLACIOLOGICAL AND CLIMATOLOGICAL CONDITIONS. St Andrews, Scotland: University of St Andrews. pp. 219. https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/10023/525/Sasha%20Leigh%20MPhil%20thesis.pdf?sequence=1. Retrieved 2017-02-16.

- ↑ J. Vandenberghe; G. Nugteren (2001). "Rapid climatic changes recorded in loess successions". Global and Planetary Change 28 (1-9): 222-30. http://shixi.bnu.edu.cn/field-trips/cooperation/ChinaSweden/the%20link/1.1.4.pdf. Retrieved 2014-11-06.

- ↑ A.A. Nikonov; M.M. Shakhnovich; J. van der Plicht (2011). "Age of Mammoth Remains from the Submoraine Sediments of the Kola Peninsula and Karelia". Doklady Earth Sciences 436 (2): 308-10. http://cio.eldoc.ub.rug.nl/FILES/root/2011/DoklEarthSciNikonov/2011DoklEarthSciNikonov.pdf?origin=publication_detail. Retrieved 2014-11-06.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Megan Gannon (2 September 2014). Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art. LiveScience.com. http://www.livescience.com/47640-abstract-neanderthal-cave-engraving-discovered.html. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Stewart Finlayson (2 September 2014). Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art. LiveScience.com. http://www.livescience.com/47640-abstract-neanderthal-cave-engraving-discovered.html. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Jean-Jacques Hublin (2 September 2014). Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art. LiveScience.com. http://www.livescience.com/47640-abstract-neanderthal-cave-engraving-discovered.html. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Harold Dibble (2 September 2014). Cave Carving May Be 1st Known Example of Neanderthal Rock Art. LiveScience.com. http://www.livescience.com/47640-abstract-neanderthal-cave-engraving-discovered.html. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ Gerhard Roth; Ursula Dicke (May 2005). "Evolution of the brain and intelligence". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (5): 250-7. http://www.subjectpool.com/ed_teach/y3project/Roth2005_TICS_brain_size_and_intelligence.pdf. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ Ralph L. Holloway (1981). "Volumetric and Asymmetry Determinations on Recent Hominid Endocasts: Spy I and II, Djebel Ihroud I, and the Salè Homo erectus Specimens, With Some Notes on Neandertal Brain Size". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 55: 385-93. http://www.columbia.edu/~rlh2/Spy1%262,IrhoudEndos.AJPA1981.pdf. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ Katie Burke (1 January 2015). Humans Made Art Earlier. Sigma Xi. http://www.qmags.com/2FE1161B1611D7DF13144AF711161D08932FF143549.htm. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Sam L. VanLandingham (May 2010). "Use of diatoms in determining age and paleoenvironment of the Valsequillo (Hueyatiaco) early man site, Puebla, Mexsico, with corroboration by Chrysophyta cysts for a maximum Yarmouthian (430,000-500,00yr BP) age of the artifacts". Nova Hedwigia 136: 127-38. http://www.pleistocenecoalition.com/vanlandingham/VanLandingham_2010b.pdf. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- ↑ Tim Radford (April 16, 2004). "World's Oldest Jewellery Found in Cave". Guardian Unlimited. http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/artsandhumanities/story/0,12241,1193237,00.html. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Michael Houmark-Nielsen (30 November 1994). "Late Pleistocene stratigraphy, glaciation chronology and Middle Weichselian environmental history from Klintholm, Møn, Denmark". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 41 (2): 181-202. http://2dgf.dk/xpdf/bull41-02-181-202.pdf. Retrieved 2014-11-03.

- ↑ Lisiecki, L.E., 2005, Ages of MIS boundaries. LR04 Benthic Stack Boston University, Boston, MA

- ↑ "African Cave Yields Evidence of a Prehistoric Paint Factory". The New York Times. 13 October 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/14/science/14paint.html.

- ↑ Janaina C. Santos; Alcina Magnólia Franca BarretoII; Kenitiro Suguio (16 August 2012). "Quaternary deposits in the Serra da Capivara National Park and surrounding area, Southeastern Piauí state, Brazil". Geologia USP. Série Científica 12 (3). doi:10.5327/Z1519-874X2012000300008. http://ppegeo.igc.usp.br/scielo.php?pid=S1519-874X2012000300009&script=sci_arttext. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- ↑ Josephine C. A. Joordens; Francesco d’Errico; Frank P. Wesselingh; Stephen Munro; John de Vos; Jakob Wallinga; Christina Ankjærgaard; Tony Reimann et al. (12 February 2015). "Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving". Nature 518 (7538): 228–231. doi:10.1038/nature13962. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v518/n7538/full/nature13962.html?foxtrotcallback=true. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ↑ Friedemann Schrenk, Stephanie Müller: Die Neandertaler, C. H. Beck, München 2005, S. 42.

- ↑ Carl Zimmer: Woher kommen wir? Die Ursprünge des Menschen. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2006, S. 90.

- ↑ John G. Fleagle; Zelalem Assefa; Francis H. Brown; John J. Shea. "Paleoanthropology of the Kibish Formation, southern Ethiopia: Introduction". Journal of Human Evolution 55 (3 2008): 360-5,. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.007.

- ↑ Kathryn Ann Bard, Steven Blake Shubert (Hgg.): Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, Psychology Press, 1999, S. 6.

External links

[edit | edit source]{{Dominant group}}