Social Victorians/People/Feversham

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Viscount Helmsley was the courtesy title for the eldest son and heir apparent of the Earl of Feversham (during the second half of the 19th century).

The people who attended the Duchess of Devonshire's fancy-dress ball from this family are the Earl and Countess of Feversham, their two youngest daughters and their husbands.

Acquaintances, Friends and Enemies

[edit | edit source]Timeline

[edit | edit source]1851 August 7, William Duncombe (at that time 2nd Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park) and Mabel Graham married.[1]

1881 July 14, Thursday afternoon, beginning about 2 p.m., William, Earl of Feversham, Mabel, Countess of Feversham and Lady Hermione Duncombe were invited to a Garden Party at Marlborough House hosted by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Wales.

1881 July 22, Friday, William, Earl of Feversham, Mabel, Countess of Feversham and Lady Hermione Duncombe were invited to — and likely attended — the party at Marlborough House hosted by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Wales.

1882 July 13, Thursday, William, Earl of Feversham, Mabel, Countess of Feversham and Lady Hermione Duncombe were invited to a Garden Party at Marlborough House for Queen Victoria hosted by the Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Wales.

1884 July 03, William, Earl of Feversham and Mabel, Countess of Feversham attended Count Münster's Reception at the German Embassy, Carlton House Terrace.

1886 July 21, Wednesday, the Earl and Countess of Feversham and the Ladies Duncombe were invited to — and likely attended — the Ball at Marlborough House hosted by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Wales.

1888 March 8, Sir Richard James Graham's father died, so he succeeded as the 4th Baronet Graham of Netherby.[2]

1889 June 27, Lady Cynthia Duncombe and Sir Richard James Graham, 4th Baronet of Netherby married.

1890 September 24, Lady Helen Venetia Duncombe and Edgar Vincent married.[3]

1891 July 9, Thursday, William, Earl of Feversham seems to have been invited to a Garden Party at Marlborough House hosted by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Wales, to which about 3,000 people were invited.

1892 May 18, Wednesday, Mabel, Countess of Feversham attended the Queen's Drawing-room at Buckingham Palace and presented Lady Ulrica Duncombe to her Royal Highness Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, who held the drawing-room on behalf of Queen Victoria.

1894 July 19, Thursday, William, Earl of Feversham and Lady Ulrica Duncombe attended a ball hosted by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire at Devonshire House that followed a dinner for the Prince and Princess of Wales, some of their children, the Russian Ambassador, the Portuguese Minister [is this de Soveral?] and a few British dignitaries and aristocratic friends and family.

1897 June 28, Monday, William, Earl of Feversham and Mabel, Countess of Feversham were invited to Queen Victoria's immense Diamond Jubilee garden party at Buckingham Palace.

1897 July 2, Friday, Lady Helen and Sir Edgar Vincent attended the Duchess of Devonshire's fancy-dress ball at Devonshire House as did Lord and Lady Feversham, the Earl and Countess Feversham. Sir R. and Lady C. Graham were also present.

1897 July 31, Saturday, William, Earl of Feversham and Mabel, Countess of Feversham gave Mabel Wombwell a "silver-gilt inkstand and candlesticks"[4] for her wedding to Henry R. Hohler.

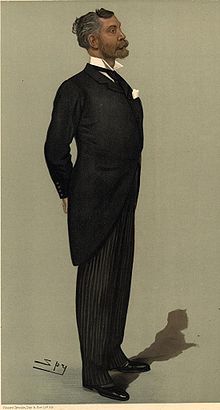

1899 April 20, a caricature portrait (above right) by Leslie Ward ("Spy") of "Eastern Finance" (Sir Edgar Vincent) appeared in this issue of Vanity Fair, as Number 746 in its "Men of the Day" series.[5] (Note the differences between the figure and the shadow in this caricature.)

1926 February 20, Edgar Vincent was created 1st Viscount D'Abernon, of Esher and Stoke D'Abernon, County Surrey.[6]

1936 March 2, Edgar Vincent succeeded as the 16th Baronet Vincent, of D'Abernon, County Surrey.[6]

Costume at the Duchess of Devonshire's 2 July 1897 Fancy-dress Ball

[edit | edit source]William, Earl of Feversham and Mabel, Countess of Feversham

[edit | edit source]William Ernest Duncombe, 1st Earl of Feversham and Mabel Violet Graham Duncombe, Countess Feversham were present at the Duchess of Devonshire's fancy-dress ball, as were their daughters Lady Helen Vincent and Lady Cynthia Graham and their husbands. Nothing is known about the costumes of the Earl and Countess of Feversham.

Lady Helen Vincent

[edit | edit source]

Lady Helen Vincent sat at Table 12 for the first seating for supper and was dressed as Contessa Valentina Gateago in the 17th-century procession.[7][8] Lady Helen's high status among the group of people attending the ball is revealed by her presence in the first supper seating.

Henry Van der Weyde's portrait (above right) of "Helen Venetia (née Duncombe), Viscountess D'Abernon as a Genoese Lady, after Vandyck" in costume is photogravure #83 in the album presented to the Duchess of Devonshire and now in the National Portrait Gallery.[9] The printing on the portrait says, "Lady Helen Vincent as a Genoese Lady, after Vandyck."[10]

Van Dyke's 1628 portrait of Anna Wake (left) does not look like the original of Lady Helen Vincent's dress, but it shows the painter's treatment of a similar subject.

Commentary on Lady Vincent's Costume

[edit | edit source]- No newspapers described or commented on Lady Helen's dress.

- Lady Vincent's dress is a hodgepodge of elements, many Victorian but with an approximately 17th-century collar and ruffled peplum. The waist is the most notable Victorian element. The ruffles (or little puffs) at the bottom of the bodice and the pearl belt emphasize and flatter her waist, as do the broad shoulders and collar. Similar ruffles (or little puffs or ruches) also appear at the neckline.

- Lady Helen's sleeves are Victorian in how short and high they are. Although the slashed puff is a 17th-century element, its silhouette echoes the shape of sleeves popular in the 1890s. The treatment of the sleeve below the single puff is odd, difficult to know what on earth the designer was thinking, how it was constructed and what keeps it above the elbow.

- Lady Helen has pulled her skirts to the front on both sides for the photograph, distorting the front panel of the skirt slightly. The skirt appears to have stripes made by stitching strips of the same satin fabric cut from the crosswise grain, which gives this very plain skirt more texture. The center piece of the skirt is reminiscent of an underskirt. This black-and-white photograph is too dark to permit clear analysis of the features of the skirt.

- The border at the bottom of the skirt and train is stiffened — probably with horsehair — preventing the fabric from hanging straight down, resulting in an A-line. In the 1890s,

Skirts were lined with cambric or taffeta and trained gowns were weighted and disciplined by facings of horsehair which might be as deep as eighteen inches at center back.[11] (532)

- This costume lacks the sophistication that would have been present in a dress designed by Mrs. Mason, for example, Mr. Charles Alias or the House of Worth. Aesthetically, the frou-frou on the top is not balanced by the simplicity of the design on the skirt and train, although, because of the stripes the costume might have looked more interesting in motion than it does in this photograph.

- The photograph appears to have been retouched on the right side of Lady Helen's waist, under her right arm, a common practice.

- Lady Helen's headdress looks like a crown because of the points made by the pearls. A single black plume rises straight up from the center of the headdress.

- Lady Helen's jewelry is primarily strands of pearls with two brooch ornaments, one pendant from one of the necklaces and the other at the center of the neckline of her bodice. Besides the several strands of pearls at her neck and on her headdress are pearls on her sleeves and at her waist.

- Lady Vincent's jewels do not display the kind of wealth that someone like the Duchess of Devonshire or Mrs. Arthur Paget, for example, had.

- The wired collar should be standing up behind her head to frame her face, but the wires cannot hold up the center back because of the cut of the lace, which should have been attached differently.

Sir Edgar Vincent

[edit | edit source]

According to the newspapers, Sir Edgar Vincent was dressed as II Conte Oravio[8] or Orayio[7] in the 17th-century procession. He is not listed as having been in the first supper seating although Lady Helen Vincent is.

Henry Van der Weyde's portrait (right) of "Edgar Vincent, Viscount d'Abernon as a Dutch Stadtholder after Frans Hals" in costume is photogravure #84 in the album presented to the Duchess of Devonshire and now in the National Portrait Gallery.[9] The printing on the portrait says, "Sir Edgar Vincent as a Dutch Stadtholder after Frans Hals."[12]

Van der Weyde's photograph of Sir Edgar Vincent is similar enough to Frans Hals's 1625-1630? portrait of Willem van Heythuyzen (left) that Hals's seems to be the original. Sir Edgar Vincent is striking a very similar pose, and even the photographer's drapery and set seem to refer to the Hals painting.

Commentary on Sir Edgar Vincent's Costume

[edit | edit source]The photograph of Sir Edgar is a close copy of the portrait of Willem van Heythuyzen by Frans Hals, but the clothing worn by the Victorian has been modified, as always, for the people at this ball, to accommodate standards of beauty contemporary to their own time. The painting is very dark, affecting our sense especially of the black-on-black details.

- In spite of the similarity between the two portraits, the doublet worn by Sir Edgar reflects Victorian rather than Elizabethan fashion.

- Sir Edgar's collar is not stiffened. The folds are more limp, suggesting a Cavalier collar, unlike the stiffened folds on the Hals portrait. But more important is that the collar in the Hals portrait has a lot of fabric, which alone can account for the fullness. Sir Edgar's collar may be starched, but it lies flatter because the costumier used so much less fabric.

- The ornament below the collar on Sir Edgar is large and probably made of lace, as is van Heythuyzen's. We cannot tell what it is or what it symbolizes.

- The fabric used for Sir Edgar's doublet and knee breeches appears to be textured, possibly a brocade or a velvet brocade. While the cloak is black like the doublet and breeches, the fabric is a more subtle, less textured brocade. Yet another fabric was used for the lining of the cloak. The textures in the fabrics are what makes this costume so sophisticated: the color is all the same.

- Sir Edgar's sleeves were made to look like they were tied to the doublet, as Elizabethan sleeves would be, but were probably sewn to it.

- The bodice of Sir Edgar's doublet is not stiffened and pointed, which changes the line of the garment, making it looser and more Victorian than Elizabethan.

- The level (rather than pointed) bodice changes the waistline and the peplum as well.

- The garments in both portraits have decorated belts or braid at the waist. Aglets are suspended from ribbon at the waistline on both portraits.

- Sir Edgar's knee breeches and sleeves are full, so they might be padded.

- Sir Edgar's white cuffs fold back from the wrists and have tiny starched pleats and lace edging (like the cuffs in Van den Weyde's portrait), but they are not as stiffly starched. The tiny tucks or pleats in van Heythuyzen's cuffs give them stiffness and texture; Sir Edgar's cuffs are looser and less controlled.

- The buttons on the sides of the breeches look decorative rather than functional.

- The ornament at the bottom of the knee breeches actually appears to be similar in size in both portraits, but Sir Edgar's is a simple bow that is less decorative than what looks like lacy, beaded trim on van Heythuyzen.

- The shoes are dominated by the bows, which may be velvet, in the Hals portrait. Sir Edgar's bows are placed below the tongue and are smaller.

- Sir Edgar's shoes have flat heels, and the tongue rises above the bow. Van Heythuyzen's shoes appear to have wooden pattens beneath the soles.

- The metal tips attached to ribbons at the waists of the men in both portraits are aglets or aiglets. Historically, breeches could be tied to the doublet with ribbons or cords whose ends were tipped with aglets. Sir Edgar's ribboned aglets are definitely decorative, but it is not clear whether Van Heythuyzen's are decorative or functional.

- Sir Edgar and Van Heythuyzen are carrying ornate cavalier rapiers. Early cavalier rapiers were long like these are, later becoming smallswords. In the portraits, the rapiers are in scabbards. Hanging from the waist of Sir Edgar's doublet is a rapier belt to hold the rapier in its scabbard. Van Heythuyzen's scabbard is quite ornate, but Sir Edgar's is simple. Both rapiers have very ornate hand guards, which is what makes them look like cavalier weapons.

- The two swords — especially the hand guards — are so like each other, did Sir Edgar find the same sword? or have this one made? Is the sword in a collection somewhere?

The Historical William van Heythuyzen

[edit | edit source]While the Times and the Morning Post say that Sir Edgar Vincent was in the 17th-century Italian procession, the description in the commemorative album associates his costume with a painting rather than a person. The man in the painting is Willem van Heythuyzen, Dutch cloth merchant and , dressed in early Cavalier style.[13] Van Heythuyzen was the founder of Hofje van Willem Heythuijsen. (A hofje is a group of almshouses surrounding an open courtyard in which poor, elderly people, especially women, can live.[14]) Hofje van Willem Heythuijsen — the hofje founded by Willem van Heythuyzen — is still in existence.[13]

Lady Cynthia Graham and Sir Richard Graham

[edit | edit source]Lady Cynthia Graham of Netherby and Princess Henry of Pless were dressed as the Queen of Sheba and led the "Oriental" Procession.[7][8]:p. 7, Col. 5b At this time, no photograph of Lady Cynthia Graham in this costume exists. (Lady Cynthia Graham is the Earl of Feversham's youngest daugther and Sir Richard Graham's second wife.)

Newspaper Accounts

[edit | edit source]Three actual accounts of Lady Cynthia's costume exist, and two are reprinted. They are not written by fashion journalists, so what her costume looked like is difficult to imagine.

- Lady Cynthia Graham "was in white satin and gauze, embroidered in gold and silver and bright rose."[15]:p. 5, Col. 7c

- "Lady Cynthia Graham appeared as Queen of Sheba, in a robe of white Bengal satin and gauze, with embroidery of gold appliqué, satin white and cerise. The manteau was of crepon de chine, covered with embroidered gauze and appliqué of coloured satin, and studded with jewels; a ceinture and pendant were of white satin, with cerise appliqué and embroidery, and she wore a jewelled headdress."[16]:p. 3, Col. 3c

- "Lovely Lady Cynthia Graham was one [Queen of Sheba], in white satin embroidered in gold and silver and bright rose."[17]:42, Col. 1b

- According to the Carlisle Patriot, reprinting the Evening Standard description (perhaps because Lady and Lord Graham were local), "Lady Cynthia Graham of Netherby also personated the famous Eastern Queen, wearing a lovely robe of white Bengal satin and gauze, with embroidery of gold applique, satin white and cerise. The manteau was of crepon de chine, covered with embroidered gauze and applique of coloured satin, and studded with jewels; a ceinture and pendent were of white satin, with cerise applique and embroidery, and she wore a jewelled headdress."[18]

- "The other Queen of Sheba, who was Lady Cynthia Graham, was charmingly attired in white and silver and rose red."[19]:p. 32, Col. 2c

Lady Cynthia Graham's original costume appeared in the Drury Lane production of The White Heather.[20]

The Queen of Sheba

[edit | edit source]Stories about the African Queen of Sheba appear in Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions. She visited King Solomon with gifts and tested his wisdom. The 9th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica does not have an article about the Queen of Sheba, although she figures in other, historical articles, like the one on Yemen.

Sir Edward John Poynter's 1890 The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (right) is in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, which accessioned it in 1892, so it would have been available for viewing until then. The Queen of Sheba's clothing here, such as there is of it, is unlikely to have been an original for the costumes worn by Lady Cynthia Graham or Daisy, Princess Pless, but her headdress has some similarities to the one worn by May Goelet dressed as Scheherazade.

Demographics

[edit | edit source]Nationality

[edit | edit source]- British

Residences

[edit | edit source]- Lady Cynthia and Sir Richard Graham: Netherby Hall in the Carlisle district of Cumbria (which is why the Carlisle Patriot coverage is so thorough)[21]

Family

[edit | edit source]- Charles Duncombe, 1st Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park (5 December 1764 – 16 July 1841)[22]

- Lady Charlotte Legge ( – 5 November 1848)[23]

- Hon. Frances Duncombe (– 15 June 1881)

- Hon. Louisa Duncombe ( – 18 November 1852)

- Charles Duncombe (1795 – 1819)

- William Duncombe, 2nd Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park (14 January 1798 – 11 February 1867)

- Reverend Henry Duncombe (25 August 1800 – 1 October 1832)

- Admiral Hon. Arthur Duncombe (24 March 1806 – 6 February 1889)

- Very Rev. Augustus Duncombe (2 November 1814 – 26 January 1880)

- Hon. Octavius Duncombe (8 April 1817 – 3 December 1879)

- William Duncombe, 2nd Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park (14 January 1798 – 11 February 1867)[24]

- Lady Louisa Stewart ( – 5 March 1889)[25]

- Hon. Gertude Duncombe ( – 24 February 1916)

- Hon. Jane Duncombe ( – 3 April 1901)

- Hon. Helen Duncombe ( – 22 November 1896)

- Hon. Albert Duncombe (11 February 1826 – 14 September 1846)

- William Ernest Duncombe, 1st Earl Feversham of Ryedale (28 January 1829 – 13 January 1915)

- Hon. Cecil Duncombe (27 May 1832 – 20 May 1902)

- William Ernest Duncombe, 1st Earl of Feversham (28 January 1829 – 13 January 1915)[26]

- Mabel Violet Graham Duncombe (15 February 1833 – 28 August 1915)[1]

- Lady Ulrica Duncombe (1874? [based on presentation at Queen's drawing-room May 1892] – 27 April 1935)

- William Reginald Duncombe, Viscount Helmsley (1 August 1852 – 24 December 1881)

- Hon. James Henry Duncombe (20 October 1853 – 10 January 1886)

- Hon. Hubert Ernest Valentine Duncombe (14 February 1862 – 21 October 1918)

- Lady Hermione Wilhelmina Duncombe (30 March 1864 – 19 March 1895)

- Lady Helen Venetia Duncombe (1866 – 16 May 1954)

- Lady Cynthia (Mabel Cynthia) Duncombe (1869 – 25 April 1926)

- Lady Helen Venetia Duncombe ( – 16 May 1954)[3]

- Edgar Vincent, 1st and last Viscount D'Abernon (19 August 1857 – 1 November 1941)[6]

- Sir Richard James Graham, 4th Bt. (24 February 1859 – 26 August 1932)[27]

- Olivia Baring (14 May 1863 – 21 March 1887)[28]

- Lady Cynthia (Mabel Cynthia) Duncombe (1869 – 25 April 1926)[29]

- Lt.-Col. Sir Fergus Frederick Graham, 5th Bt. (10 March 1893 – 1 August 1978)

- Richard Preston Graham-Vivian (10 August 1896 – 30 September 1979)

- Daphne Graham (17 March 1903 – )

- Charles William Reginald Duncombe, 2nd Earl of Feversham (8 May 1879 – 15 September 1916)[30]

- Marjorie Blanche Eva Greville Duncombe (25 October 1884 – 25 July 1964)[31]

- Lady Mary Diana Duncombe (19 March 1905 – October 1943)

- Charles William Slingsby Duncombe, 3rd Earl of Feversham (2 November 1906 – 4 September 1963)

- Hon. David William Ernest Duncombe (8 February 1910 – September 1927)

Also Known As

[edit | edit source]- Family name: Duncombe

- Earl Feversham of Ryedale

- Viscount Helmsley

- Baron of Feversham

- William Ernest Duncombe (11 February 1867 – )[26]

- Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park

- Other Duncombe families existed as well.

Questions and Notes

[edit | edit source]- The newspapers call the Earl and Countess Feversham Lord and Lady Feversham.

- The Times article lists Sir R. and Lady C. Graham[7]: if Lady C. Graham is Lady Cynthia, then Sir R. Graham is Sir Richard James Graham.

- Also present at the ball and accounted for on the Duncombe page are the following: Alicia Duncombe, Lady and Mr. Florence Duncombe.

- Present at other social events and not accounted for were the following: Caroline Duncombe and the Misses Duncombe.

- William Duncombe, 1st Earl of Feversham is #443 on the list of people who attended the Duchess of Devonshire's 2 July 1897 fancy-dress ball; Mabel, Countess Feversham is #444; Lady Helen Vincent is #215; Sir Edgar Vincent is #226; Sir Edgar Vincent is #226; Lady Cynthia Graham of Netherby is #220; Sir Richard James Graham is #464.

Footnotes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Mabel Violet Graham." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Sir Frederick Ulric Graham, 3rd Bt." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Lady Helen Venetia Duncombe." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Marriage of Mr. H. R. Hohler and Miss Wombwell." Morning Post 2 August 1897, Monday: 6 [of 8], Col. 3a–c [of 7]. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000174/18970802/067/0006 (accessed June 2019).

- ↑ "List of Vanity Fair (British magazine) caricatures (1895–1899)". Wikipedia. 2024-01-14. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_Vanity_Fair_(British_magazine)_caricatures_(1895%E2%80%931899)&oldid=1195518024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Vanity_Fair_(British_magazine)_caricatures_(1895%E2%80%931899).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Edgar Vincent, 1st and last Viscount D'Abernon." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Ball at Devonshire House." The Times Saturday 3 July 1897: 12, Cols. 1a–4c The Times Digital Archive. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Fancy Dress Ball at Devonshire House." Morning Post Saturday 3 July 1897: 7 [of 12], Col. 4a–8 Col. 2b. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000174/18970703/054/0007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Devonshire House Fancy Dress Ball (1897): photogravures by Walker & Boutall after various photographers." 1899. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait-list.php?set=515.

- ↑ "Helen Venetia (née Duncombe), Viscountess D'Abernon as a Genoese Lady, after Vandyck." Diamond Jubilee Fancy Dress Ball. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw158441/Helen-Venetia-ne-Duncombe-Viscountess-DAbernon-as-a-Genoese-Lady-after-Vandyck.

- ↑ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume: From the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century. Harper & Row, 1965.

- ↑ "Edgar Vincent, Viscount d'Abernon as a Dutch Stadtholder after Frans Hals." Diamond Jubilee Fancy Dress Ball. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw158442/Edgar-Vincent-Viscount-dAbernon-as-a-Dutch-Stadtholder-after-Frans-Hals.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Willem van Heythuysen". Wikipedia. 2023-08-27. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Willem_van_Heythuysen&oldid=1172477813. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willem_van_Heythuysen.

- ↑ "Hofje". Wikipedia. 2023-08-09. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hofje&oldid=1169559641. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hofje.

- ↑ "Duchess of Devonshire's Fancy Ball. A Brilliant Spectacle. Some of the Dresses." London Daily News Saturday 3 July 1897: 5 [of 10], Col. 6a–6, Col. 1b. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000051/18970703/024/0005 and https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000051/18970703/024/0006.

- ↑ “The Ball at Devonshire House. Magnificent Spectacle. Description of the Dresses.” London Evening Standard 3 July 1897 Saturday: 3 [of 12], Cols. 1a–5b [of 7]. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000183/18970703/015/0004.

- ↑ “Girls’ Gossip.” Truth 8 July 1897, Thursday: 41 [of 70], Col. 1b – 42, Col. 2c. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0002961/18970708/089/0041.

- ↑ "Fancy Dress Ball: Unparalleled Splendour." Carlisle Patriot Friday 9 July 1897: 7 [of 8], Col. 4a–b. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000365/18970709/084/0007.

- ↑ “The Duchess of Devonshire’s Ball.” The Gentlewoman 10 July 1897 Saturday: 32–42 [of 76], Cols. 1a–3c [of 3]. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003340/18970710/155/0032.

- ↑ "The Morning’s News." London Daily News 18 September 1897, Saturday: 5 [of 8], Col. 2b. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000051/18970918/027/0005.

- ↑ "Arthuret". Wikipedia. 2021-05-08. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Arthuret&oldid=1022099353. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthuret#Netherby Hall.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Charles Duncombe, 1st Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park." "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Lady Charlotte Legge." "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "William Duncombe, 2nd Baron Feversham of Duncombe Park." "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Lady Louisa Stewart." "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "William Ernest Duncombe, 1st Earl of Feversham of Ryedale." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ↑ "Sir Richard James Graham, 4th Bt.." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Olivia Baring." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Lady Mabel Cynthia Duncombe." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 " Charles William Reginald Duncombe, 2nd Earl of Feversham of Ryedale." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Lady Marjorie Blanche Eva Greville." "Person Page". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- ↑ "Charles Duncombe, 2nd Earl of Feversham". Wikipedia. 2020-09-12. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charles_Duncombe,_2nd_Earl_of_Feversham&oldid=978075739.