Social Victorians/People/de Soveral

Overview

[edit | edit source]Favorite of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Wales

[edit | edit source]Luís de Soveral was among King Edward VII's three most important friends and advisors.[1]:259

Soveral was the "favorite" of Alexandra, Princess of Wales, who had longstanding hearing loss[2]: "He was Alix's favorite, filling the place in her affections left by Oliver Montagu; he always danced the first waltz at every ball with her, and he knew how to pitch his voice in a way that made it possible for her to hear."[3]:480 (of 918)

Jane Ridley summarizes and quotes from Daisy Pless's diaries after Queen Alexandra's 65th birthday on 1 December 1909 (Alix is Alexandra):

She noticed that Alix always sat side by side with Soveral; "he speaks distinctly and she always hears him." Like Alix, Soveral was fanatically anti-German.[3]:627 (of 918)

It is Daisy, Princess Pless who sees Alexandra and Soveral as fanatic.[4] (186)

Soveral's Popularity, Intelligence and Political Acuity and Work

[edit | edit source]In The Proud Tower, Barbara Tuchman describes Soveral — who never married — as "the ugly, fascinating and ribald Marquis de Soveral, Ambassador of Portugal,"[5]:125 (of 1186)

the notorious Marquis de Soveral, who represented Portugal. An intimate friend of King Edward, he was known as the "Blue Monkey" in London society where it was said, "he made love to all the most beautiful women and all the nicest men were his friends."[5]:623 (of 1186)

In his 1925 biography of Edward VII, Sidney Lee says,

Among the more intimate friends of the King and members of the inner circle of the court were several foreigners. One of the most important of these was the Portuguese Marquis de Soveral, who had been successively since 1885 First Secretary of the Portuguese Legation and Portuguese Minister in London (save during the years of 1895-97, when he returned to Lisbon as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs). Tall and well built, with blue-black hair and a fierce moustache, with his invariable monocle, white buttonhole, and white gloves, he went everywhere and was everywhere persona gratissima. He had great social and diplomatic gifts. More important still, he had few equals as a raconteur. His unique position as “the most popular man in London” had been gained by a singular charm of manner and a tact equal to that of the King himself. “Why did you wait for an invitation?” said the King on one occasion when the name of the Marquis had been omitted by mistake from the list of weekend guests at Sandringham; “why didn’t you come without?” Soveral, who had just contrived to arrive in time for dinner in response to an urgent telegram, did not make the obvious reply that one could not intrude upon a King unasked. He staggered his fellow-guests by remarking in his best manner, “Well, Sir, I had got as far as my door when your command arrived.” Portuguese through and through, cosmopolitan by training, diplomatic by choice and temperament, a courtier and a man withal, a warm friend without enemies, genial, merry, and loquacious, Soveral filled a place that no foreigner has held in England within living memory, and well earned the epithet of “Soveral überall.” Of King Edward he was a trusted companion in England and abroad, and to Soveral it was due in large measure that King Edward’s first state visit after his accession was paid to the Court of Lisbon. His loyalty and discretion were beyond reproach, as was the goodness of heart that saved him, as the same quality often saved King Edward, from errors into which statesmen reputedly abler frequently fell. After the Portuguese revolution of 1908 and the King’s death in 1910, / Soveral preferred impoverishment and the comparative obscurity it entailed rather than to enrich himself by writing his memoirs. To him confidences were sacred — even when those from whom he had received them had passed away. A gallant gentleman and a grand seigneur, he proved more than worthy of the great trust the King reposed in him.[6]:59–60

In his account of Edward VII's "Social and Diplomatic Life," Gordon Brook-Shepherd mixes very high praise with an odd reading of "Blue Monkey" as positive:

Finally, the man who, outside the Prince's immediate family, came, together with Alice Keppel, to stand closer to his affections and his confidence than anyone in the kingdom. This was the Portuguese nobleman, diplomatist, courtier and ladies' man par excellence, the Marquis Luis [sic] Augusto Pinto de Soveral, known to two generations of Europeans as the "Blue Monkey." This genial figure, with his curled black moustache, black imperial beard, heavy black eyebrows — all set off against the white flower in his buttonhole and the white kid gloves in his hand — had about him an aspect which was dandified but (with the swarthy almost simian virility which had given him that nickname) also manly. He was a remarkable figure in his own right as well as for the unique position he was eventually to hold with the British crown. For if his royal friend became Europe's uncle, Soveral became its darling. Of all the stars that twinkled in the Edwardian firmament, his twinkled the brightest.

This was remarkable in that, though of an old Portuguese family, he was not born one of the grandees of Iberia. His father was, in fact, a Visconde or Viscount, and Luis was only to be created a Marquis by the King of Portugal in 1900, as a reward for his personal and political services. Neither did he possess any huge estates, nor inherit or accumulate any great fortune. Indeed, it is clear that he did not always find it easy to live on the sumptuous private scale required of him. This money problem could have been one reason why he never married, though the bewildering profusion of women who floated in and out of his life is a more likely explanation.

It was the qualities of the man himself, therefore, that were mainly responsible for his phenomenal success. He was a great raconteur and conversationalist in an age that prized good conversation and had time for it. His wit became a household word in Edwardian society, yet it was never barbed. Brilliant people are often rude. Discreet people are often dull. Soveral's combination of brilliance and discretion was the first of his many rare qualities. Another was the ability — one that is difficult to analyze but easy to recognize — of being both a man's man and a woman's man. the ladies never begrudged him his masculine club evenings. His men friends never seemed to be jealous (even if they could not help being envious) of his phenomenal success with the ladies. With the exception of a few politically inspired attacks, not a harsh word is recorded against him. Nor was he ever tactless or spiteful / or sarcastic about anyone in return. Even the countless husbands he cuckolded seem to have been prepared to forgive him everything for such gentleness.[7]:61–62

In her biography of "Bertie," the Prince of Wales, Ridley describes Soveral and ends with a mention of another very close associate of the Prince of Wales, Ernest Cassel:

Soveral, the Portuguese minister in London, was known as the Blue Monkey. His blue-black hair, jet-black imperial beard and heavy eyebrows, and the white flower in his buttonhole make him instantly recognizable among the faces lined up for the innumerable royal photographs. Bertie [the Prince of Wales] had known him since 1884, but it was after 1897 that Soveral became a central figure at Marlborough House. In August 1899, he accompanied the prince to Marienbad for his cure, and Bertie found him a "charming" traveling companion and "a great resource." ... Soveral's clowning belied a sharp mind, and he was exceptionally well informed on European politics. He was flirtatious and liked to pose as a lady-killer. Being infinitely discreet, he conducted several flirtations at the same time. ...

Have you seen The Importance of Being Ernest? Bertie asked Soveral. "No, Sir," came the answer, "but I have seen the importance of being Ernest Cassel."[3]:479 (of 918)

Ralph Martin, in his biography of Lady Randolph Churchill, says that

As one of King Edward's three closest friends, Soveral was usually invited wherever His Majesty was invited. He was the Portuguese Ambassador to Great Britain, and few were better informed on European politics; indeed it was said that "had he wished he / could have become one of Europe's leading statesmen. ... [sic]" ...

He was a genial, charming, and tactful bachelor, with a fund of risqué stories. Always dressed at the height of fashion, he usually wore immaculate white gloves and a white flower in his buttonhole. He had a swarthy complexion and wore a fashionable moustache, and the press often referred to him as "The Adonis of Diplomacy." ... His collection of court ladies was referred to by one woman as a "harem."[1]:259–260

Soveral and Hugh Guion and Lady Macdonell were in Berlin in 1876 as diplomats (the Macdonnells' tenure was 1875-1878). Their social life included the Crown Prince Frederick and Princess Victoria, who married on 25 January 1858 (their silver anniversary would have been 25 January 1883 if the celebration was held exactly 25 years later). Lady Macdonnell says in her memoirs of their time in Berlin,

We had many charming colleagues: among them Count Maféi and Louis Soveral, to-day Marquis de Soveral. He was educated at Louvain, and was to have been a sailor, but changed his mind and became a diplomatist. We have often laughed since, talking of the time when we used to give him English lessons; for at that period he could not speak a word of the language that was to become so familiar to him in later years. He was as popular then as he has always been since.

M. de Soveral's great characteristic was tact, which naturally is a great asset to a diplomatist. A good example of this occurred when he was called by King Carlos to take the portfolio of Minister of Foreign Affairs on the death of Count Lobo D'Avila. Before even presenting himself to the King, the Marquis hurried to the bereaved parents of the deceased / Minister, the Count and Countess Valborn, to offer his condolences. I have a photograph of him at the fancy dress ball given at the Crown Prince's Palace on the anniversary of Their Imperial Highnesses' silver wedding; he is dressed in the costume of a Troubadour. Louis Soveral was always the life and soul of the diplomatic parties.[8]:134–135

Soveral played the guitar (probably the Portuguese guitar) and sang fado, a genre of Portuguese music associated with Lisbon and the university town of Coimbra.[9] Fado's tone is one of saudade, a Portuguese word suggesting irreparable loss with longing for what has been lost, a kind of grief but with more emphasis on the longing and less on the sadness.[10]

According to the Portuguese Wikipedia Luís de Soveral

was considered the most elegant man in London who dictated fashion in Piccadilly and, for the ladies, the most charming man. In addition to these attributes, at least as a young man, he played the guitar and sang fado and, when he hosted a dinner abroad, he treated his friends to a [traditionally Portuguese] dish of cod accompanied by champagne [translation by Google Translate].[11]

Soveral came from the Duoro River valley, a wine-making region of Portugal and the source of Port, which (similar to champagne) has to come from this region to be called Port:

Translation by Google Translate:

As a man from the Douro, where he was the owner and producer of wines, he officially participated in the defense of the "Porto" denomination worldwide.][11]

The Portuguese Wikipédia article on Soveral goes on to say (translation of the Portuguese by Google Translate),

According to the English writer Virginia Cowes [i.e., Cowles], the Marquis of Soveral was a "charming, urbane, polished and witty man. He adored women and was considered the best dancer in Europe" and, to quote Sir Frederick Ponsonby, a contemporary of his, "he was universally popular in England... where he made love to all the most beautiful women and where all the important men were his friends."][11]

Gordon Brook-Shepherd says of Soveral's popularity with women,

The women, in particular, he bowled down like ninepins. In an age of stylish philanderers, Soveral stands out as the greatest ladies' man of them all. There is no end, in his papers, to these souvenirs of his distinguished conquests, souvenirs that range from bundles of letters on every sort of crested notepaper to hastily scribbled messages on the back of a banquet menu or a carnet de bal, or even plain telegrams that still manage to vibrate.[7]:144

Brook-Gordon begins a list of "conquests" from the letters in the Soveral archive.

Discussing the boredom women could feel at shooting parties, Jonathan Ruffer says,

The more thoughtful hosts invited gentlemen who showed no talent for shooting, but whose wit made up for it. These "darlings" were usually drawn from court circles, and one of the best of them was the Portuguese minister in England, the Marquis de Soveral. Despite an unprepossessing exterior (he was fondly known as the Blue Monkey), he had that rare talent of keeping people amused — even King Edward VII, when the strain of office and bronchial troubles made him progressively more difficult to please. It was clear, too, that Queen Alexandra found de Soveral enjoyable company. He was a wonderful raconteur — to the point, sometimes, of monopolizing the conversation. On one occasion Prince Francis of Teck remarked to him: "My dear Soveral, would you mind if I slipped a word in every five minutes and a phrase every half hour?" Daisy, Princess of Pless points to a similar trait. Staying at a house party at Chatworth in 1907, she wrote: "Only Soveral was furious; he was rather the odd man out, which was a rule he never is."[12]:82

Daisy, Princess of Pless and Soveral's Opposition to Germany

[edit | edit source]To Daisy, Princess of Pless Soveral was in 1909 "almost a dangerous fanatic in his feelings against Germany, the danger to England, and so on"[4]:186 and "a firebrand against Germany," but then she was married to Hans Heinrich XV Prinz von Pless and urged Germany's case with Edward VII.[4]:202 After Edward VII's death, she writes in her diary in 1912 of Soveral and Cassel and reports arguing Germany's case with George V:

People are ambitious and people are snobs. Sir Ernest Cassel and Soveral ought to be expelled — or go peacefully — to another world; but they both have the ear of England, and Soveral is a personal friend of the present King — whom I ventured to advise to learn and think and judge for himself and not to believe the foreign political ideas of Soveral. He agreed and did not mind my saying this to him. Cassel said to me at a diimer in January:

“You seem to have all gone mad in your country."

I only answered:

“I suppose you mean in your country" (as I believe he is a German).[4]:238

The Princess of Pless is quite nasty about Soveral as early as 1903, in part because of his political alliances against Germany and her loyalty to it and to Kaiser Wilhelm II but also, it sounds, something personal:

Soveral, the Portuguese Minister, is the oddest character at present in English Society; he imagines himself to be a / great intellectual and political force and the wise adviser of all the heads of the Government and, of course, the greatest danger to women! I amuse myself with him as it makes the other women furious, and he is sometimes very useful. He is so swarthy that he is nicknamed the "blue monkey" and I imagine that even those stupid people who believe that every man who talks to a woman must be her lover, could not take his Don Juanesque pretensions seriously. Yet I am told that all women do not judge him so severely and some even find him très séduisant. How disgusting! Anyway, from now on I will not go alone with him to the theatre or to lunch at a restaurant. He hates the German Emperor and I am sure has a very bad influence on King Edward in this direction. It is simply that his prodigious vanity is wounded because he imagines that the Emperor does not care for him and does not fuss over him when visiting England. Why should the Emperor rush at him? After all, Delagoa Bay[1] is not the one point around which the world revolves.

fn1: Discovered by Portugal in 1502: the subject of repeated disputes between Portugal and Great Britain, the last in 1889.[13]:78–79

It sounds like some gossip about them stung her into this distasteful diatribe. Her memoirs describe a number of arguments about Germany, many between her and Soveral.

But they were thrown together socially, and in another description from 1903, she complains that good male conversationalists are difficult to come by, but "Soveral is the most agreeable conversationalist of them all — and he is a foreigner."[14]:99 In an undated letter she refuses to be rejected by him:

You are simply getting bored with me and that's the truth. ... No my dear, I am not going to be taken up one moment & dropped the next. ...

Now that I have said all that I feel better. Let me know tomorrow if you are coming for lunch or not.

Yours,

Daisy [sic ellipsis points][1]:260

She seems wrong in her estimation of his intelligence, political acuity and popularity, and she reads his opposition to the Kaiser as personal, when it far more likely that Soveral's opposition is political. And history has proved Soveral and not Daisy, Princess of Pless correct about the Kaiser and Germany.

Negative Commentary on Soveral

[edit | edit source]Kaiser Wilhelm II, son of Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia (Queen Victoria and Albert's eldest daughter), is who called de Soveral the "blue monkey."[15] Roderick McLean says that Soveral was "offended" when the Kaiser called him "'the blue monkey' to his face."[16]:178 While Brook-Shepherd says the nickname was affectionate, Kaiser Wilhelm was not sympathetic to Soveral. The blue might suggest a ribald sense of humor, but McLean says the blue referred to Soveral's "blue-black hair,"[16]:140 and many others assume it. Perhaps the monkey is about, as Brook-Shepherd says, "simian" hairiness and "virility."[7]:61

Daisy, Princess of Pless, who is elsewhere quite nasty about Soveral, writes in her first memoir: "Soveral never would let one lady know about another. Above all, the King and Queen were not to be told. ... For such a careful diplomat he was sometimes guilty of bad breaks. Nothing is more stupid than unnecessary secrets."[4]:122–123 They traveled in the same circles — perhaps they were thrown together because of their mutual relationship with the Prince of Wales and then Edward VII — but her strong feelings are unkind and different from what most people seem to have felt.

Anita Leslie reports, without attribution, that Soveral was "reputedly the illegitimate son of Edward's friend, King Carlos of Portugal."[17]:262

Acquaintances, Friends and Enemies

[edit | edit source]Friends

[edit | edit source]- Queen Victoria

- Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales

- Alexandra, Princess of Wales

- Alice Keppel

- Winston Churchill[1]

"Conquests"

[edit | edit source]- Princess Henriette de Lieven[7]:145

- Leonie Leslie[7]:145

- Muriel Wilson[7]:145

- Lady Gladys de Grey[7]:145

- Princess Margaretha[7]:145

- "E. von R." (wife of an Austrian or possibly a German diplomat)[7]:145–146

- Daisy, Princess of Pless (complex relationship that included vitriol)

Organizations

[edit | edit source]- Marlborough House Set

- Diplomatic service

- The Prince of Wales's Inner Circles

- Lord Carrington, Charles Robert Wynn-Carrington[18] (1876, less influential by 1905[17]:296)

- Lord Esher, William Baliol Brett, 1st Viscount Esher (his best friend according to Leslie[17]:81)

- Sir Ernest Cassel

- Alice Keppel

- Honors

- The British Order of St Michael and St George, Honorary Knight Grand Cross (1897 January 12)[19]

- The (British) Royal Victorian Order, an order created in 1896 by Victoria and from the beginning open to "foreigners" as well as British people,[20] Honorary Knight Grand Cross (1902)[19]

- The Ancient and Most Noble Military Order of the Tower and of the Sword, of Valour, Loyalty and Merit, "the pinnacle of the Portuguese honours system."[21]

- "Life's Vanquished": "In the eighties he was part of 'Os Vencidos da Vida,' the dinner group of intellectuals who believed that Portugal could modernize and reach the level of Europe at the time, which included Eça de Queiroz, Oliveira Martins, Guerra Junqueiro, Ramalho Ortigão, among others, who considered King D. Carlos himself an alternate member of the group."[11]

Timeline

[edit | edit source]1876, Hugh Guion Macdonell was diplomat in Berlin 1875-1878, where Queen Victoria and Albert's eldest, Princess Royal Victoria was the Crown Princess of Germany and Prussia, later to be the Empress Frederick. Soveral was the Secretary of the Portuguese Legation at Berlin in 1876 and also attended a fancy-dress ball in honor of the Crown Prince and Princess's "silver wedding," their 25th anniversary.[8]:116, 135

1880s, de Soveral was part of Os Vencidos da Vida ("Life's Vanquished"), a social group or network of intellectuals.

1883 January 25, Soveral attended a fancy-dress ball in Berlin in honor of the "silver wedding" (their 25th) anniversary of Crown Prince Frederick and Princess Royal Victoria.[8]:116, 135

1885, Luís Pinto de Soveral was First Secretary at the London Embassy.[19]

1890 January 11, the 1890 Ultimatum, a memorandum from Prime Minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury to the Portuguese government, "claiming sovereignty over territories, some of which had been claimed as Portuguese for centuries,"[22] in spite of many centuries of treaties and a very long relationship as allies. Essentially, the British government was supporting decisions made locally in Africa, against instructions, to protect settlements and land claimed by autonomous non-governmental agents and fortune-seekers like Cecil Rhodes. Ultimately, the humiliation many Portuguese experienced with "the 1890 ultimatum was said to be one of the main causes for the Republican Revolution, which ended the monarchy in Portugal 20 years later (5 October 1910), and the assassination of the Portuguese king (Carlos I of Portugal) and the crown prince (1 February 1908)."[22]

1890s middle, "In the mid-1890s, he [de Soveral] was the mediator of England's dispute with Brazil over the Island of Trindade, which England had occupied because it considered abandoned. After analyzing the issue, the Marquis concluded in favor of Brazil, a decision that was accepted by England" [rough translation by Google Translate].[11]

1891, Luis Pinto de Soveral was Minister from Portugal to London.[19]

1893 January – 1902, Hugh Guion Macdonell was posted to Lisbon as diplomat to Portugal, arriving January 1893. Lady Anne Macdonnell says in her memoirs,

We had the great pleasure of renewing our acquaintance with Louis Soveral (now the Marquis). Of course, it was of immense importance that Hugh should have long conferences with him, as our relations with Portugal had been somewhat strained, and our respective countries were not the best of friends, due mainly to an incident similar to that of the French and Fashoda.[8]:223

1895–1897, Luís Pinto de Soveral was Minister of Foreign Affairs in Portugal.[19]

1895 February 2, Friday, Luís Pinto de Soveral attended the Countess of Warwick's bal poudré dressed as "Mousquetaire of the 2nd Company of the Royal Household, Louis XV." The Leamington Spa Courier called him "The Portuguese Minister (Don Louie Louveral" [sic no paren].[23]:6, Col. 5a

1896 January, Gordon Brook-Shepherd says,

In January of 1896, when relations between England and Germany were near breaking-point over the mounting crisis between the English and the Boers in southern Africa, Soveral nipped all ideas of German military intervention in the bud by announcing flatly that not one German soldier would be allowed to land at Portuguese Lorenzo Marques, the only sea-base from which a force from German East Africa could march inland. Soveral's first thought in this was to help his English friends, but he may also have prevented a European conflict in the process.[7]:63

1897 later, Luís Pinto de Soveral was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St James's from Portugal.[19]

1897 July 2, Friday, M. de Soveral attended the Duchess of Devonshire's Duchess of Devonshire's fancy-dress ball at Devonshire House.

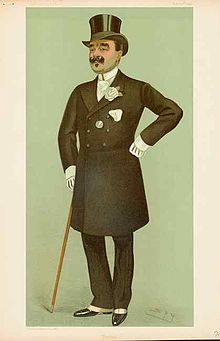

1898 February 10, a caricature portrait (above right) called "Portugal" by Leslie Ward ("Spy") was published in the 10 February 1898 issue of Vanity Fair, as Number 704 in its "Men of the Day" series.[24]

1899 August, Soveral "accompanied the prince [of Wales] to Marienbad for his cure, and Bertie found him a 'charming' traveling companion and 'a great resource.'"[3]:479 (of 918)

1899 October 14, de Soveral and Prime Minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury signed of the 2nd Treaty of Windsor to resolve "the difficult situation in Luso-British relations" resulting from the 1890 Ultimatum.[11]

1900, King Carlo I created de Soveral a Marquis, which title became extinct upon his death in 1922.

1900 June 3, Sunday, Whit Sunday, de Soveral was present at a Whitsun house party at Sandringham House. Anita Leslie says his "caustic wit always lightened Edward's humour."[25]:195 1900 June 28, Thursday, Soveral attended the wedding of Lady Randolph Churchill and George Cornwallis-West.[1]:221 1902 February 13, Thursday, Soveral was present at Niagara, a skating rink, with King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra and some of their friends.

1902 August 9, planned for 26 June 1902,[26] de Soveral was Ambassador Extraordinary (and thus probably a representative of King Carlo I of Portugal rather than more generally the government[27]) at the coronation of King Edward VII.[19] Just after the coronation ceremony Louise, Duchess of Devonshire tried "to reach the Ladies' [restroom] before anyone else":

After the long ceremony she tried to hurry out in the wake of the royal procession, but found herself stopped by a line of Grenadier Guards. Leonie [Leonie Leslie] and Jennie [Lady Randolph Churchill], who were descending from the King's special box, heard her upbraiding the officers in front of all the other peeresses, many of whom were themselves most uncomfortable. Then, trying to push her way past them, she missed her footing and fell headlong down a flight of steps to roll over on her back at the feet of the Chancellor of the Exchequer [Michael Hicks Beach], who stared paralyzed at this heap of velvet and ermine. The Marquis de Soveral swiftly took charge of the situation and had her lifted to her feet while Margot Asquith nimbly retrieved the coronet, which was bouncing along the stalls, and placed it back on her head. It was a moment in which younger women naturally had to give precedence to an angry Duchess.[25]:190

1903 Spring, the Prince of Wales

sailed for Portugal on the Victoria and Albert, taking with him seventy pieces of luggage. In addition to Charles Hardinge and Fritz Ponsonby, he brought the Marquis de Soveral, the Portuguese minister. These men composed an inner court, but of the three, only Soveral was privy to Bertie's plans. / Bertie made his entry into Lisbon wearing his uniform as colonel of a Portuguese cavalry regiment, an exceptionally short jacket that "was not becoming to a stout man," as it revealed a large expanse of breeches.6 Etiquette dictated that only the two kings could sit while all others had to stand, enduring not only a pigeon-shooting competition but also the gala opera that followed. The King [of the U.K.] was not impressed by the Portuguese nobility, who he thought looked "like waiters at second-rate restaurants." They all had hopes of receiving the Royal Victorian Order, wrote Ponsonby, "but as the first three are said to be disloyal and it would be difficult to give it to No. 4, none of them were given it."[3]: 64% — 535–536 (of 918)

[fn 6] Ponsonby, Three Reigns, p. 155.

1903 later in the Spring, the tour that began in Portugal went on to Paris. At one luncheon, King Edward VII

sat between two attractive women he had known and favoured for years as Prince of Wales: the Countess de Pourtalès on his right, and the Marquise de Jaucourt on his left. Among the rest of the fifty guests at the large Embassy table were Madam Henry Standish (the elegant and high-born French lady who always insisted that née des Cars was put after her American husband's name); Prince d'Arenberg, the President of the French Jockey Club, whose guest the King was soon to be; the Marquis de Breteuil and the Marquis de Gallifet; and Prince Mohamed Ali, brother of the Khedive of Egypt. To the King, one and all were fond and familiar faces of his Parisian scene. Soveral was there as well ....[7]:198

1904 January 6, Twelfth Night, the Duchess of Devonshire hosted a Twelfth Night house party:

Bertie and Alix attended Louise Devonshire's Chatworth Twelfth Night house party for the first time as King and Queen (they had stayed often as Prince and Princess of Wales) in 1904. Balfour was also present. While the King rode off to the shoot on his cob, the prime minister played golf. ... Alix was the party's life and soul. On the last evening she danced a waltz with Soveral, and then everyone took off their shoes to see what difference it made to their height. Daisy Pless, who excelled in the private theatricals, noted in her diary that "The Queen took, or rather kicked hers off, and then got into everyone else's, even into Willie Grenfell's old pumps. I never saw her so free and cheerful — but always graceful in everything she does."[15]:551 (of 918)

1906 July, Daisy, Princess of Pless writes in her first memoir,

When I was in London in July, Soveral motored me to see Hampton Court and the lovely gardens. We then hired a man to punt us down the river and lunched tied to the banks of a side stream. On the way back we ran into a Regatta at Kingston, but could not watch it as I had to be back in time to dine at White Lodge. This excursion was to be kept a secret, goodness knows why; but Soveral never would let one lady know about another. Above all, the King and Queen were not to be told. One day at Cowes, to Soveral’s horror, the two sons of Princess Beatrice began: “Oh, we saw you at the Regatta the other day ——” Soveral hushed them up, changed the conversation quickly and Queen Alexandra, being deaf, did not hear. For such a careful diplomat he was sometimes guilty of bad breaks. Nothing is more stupid than unnecessary secrets. One day he and I went into Cowes and he bought two brooches with the King’s yachting pennant in enamel; one he gave / to me and the other he later on gave to the Queen. We were racing in the Britannia a day or two afterwards when the Queen showed me hers and then exclaimed: “Oh, you have one too.” To tease her a little I could not resist saying: “Yes, ma’am. Soveral and I bought them together in a shop at Cowes.”[4]:122–123

Daisy implies that she bought one brooch and Soveral the other, perhaps to protect Soveral in a way, or perhaps just to say she was present when they were bought.

1907 January 6, Twelfth Night, the Duchess of Devonshire hosted another Twelfth Night party at Chatsworth House. The informant is Daisy, Princess Pless:

It was the same huge party as usual, only Soveral was furious; he was rather the man out, which as a rule he never is! ... Soveral generally went down and smoked / a cigar alone in the smoking room ....[4]:126

1907, 15 June to 18 October, de Soveral was Ambassador Extraordinary to the Second Hague Conference,[19] a series of meetings to develop agreements on conduct in wartime.[28]

1910 March 8, King Edward VII traveled to Biarritz from Paris by train. He was so sick that Alice Keppel wrote Soveral: "The King's cold is so bad that he cannot dine out but he wants us all to dine with him at the Palais, SO BE THERE. I am quite worried entre nous and have sent for the nurse."[3]:637 (of 918) Anita Leslie says, "He received hardly any visitors except Mrs. Keppel, and Soveral, who never fatigued him."[17]:304

1910 May 6, King Edward VII died. According to Ridley, "Soveral, who was with the King during his illness in Biarritz, was convinced that he was killed by his doctors."[3]:653 (of 918)

1910 May 8, Wednesday, after the funeral on 7 May King Edward lay in state in St. Stephen's Hall, and many thousands of mourners came. Late at night on Wednesday, 8 May, Soveral went:

Soveral made a late-night visit on Wednesday with the King of Portugal. Carrington received them as Lord Chamberlain and wrote that Soveral was "terribly pale and upset. He held my hand for quite two minutes saying over and over again, 'This is too awful.'"[3]:660 (of 918)

1911, Coronation Summer, "At a party given by Mrs. Hwfa Williams and entertained by the wit of the Marquis de Soveral, the conversion was so generally enjoyed that the guests who came to lunch stayed until one o'clock in the morning."[5]:662 (of 1186)

1922 October 5, Soveral

ended his days in Paris in 1922, with Queen D. Amélia [of Portugal] accompanying him in his last moments, who had great esteem for him since his years of dedication to the service of King D. Carlos and Portugal as diplomat, as a minister, as an advisor, as a friend at all times.[11]

Costume at the Duchess of Devonshire's 2 July 1897 Fancy-dress Ball

[edit | edit source]

At the Duchess of Devonshire's 1897 fancy-dress ball, M. Luís Pinto de Soveral went as Count d'Almada, C.E. 1640, and sat at Table 2 in the first seating for supper.[29]:7, Col. 5–6 He escorted Gwladys, Countess de Grey, following the Duke of Devonshire and Alexandra, Princess of Wales. He would likely have sat next to the Princess of Wales.

W. & D. Downey's portrait of Luis Maria Augusto Pinto de Soveral as Count d'Almada, C.E. 1640 in costume is photogravure #30 in the album presented to the Duchess of Devonshire and now in the National Portrait Gallery.[30] The printing on the portrait says, "Mons. de Soveral as Count d'Almada (A.D. 1640)."[31]

The portrait of Don Antão Vaz de Almada (right), which is in the collection of the Lisbon Military Museum, was painted in 1904 by Artur de Melo, and thus cannot be the original for the costume Luis de Soveral is wearing.[32]

The Historical Count d'Almada

[edit | edit source]Count d'Almada, C.E. 1640 is probably Don Antão Vaz de Almada, 7th Count of Avranches (1573–1644).[33] He was never Count d'Almada, a title not created until 1793.[34] He was a count and his last name was Almada, but he was not Count Almada.

Almada is a national hero because he was one of the main "forty conspirators"[35] during the 1640 Portuguese Restoration War, a revolution against the Castilian government of Spain.[36] He was ambassador to England 1641–1642,[33] during the reign of Charles I, who was executed in 1649.[37] Almada succeeded in 1642 in securing England's recognition of the Kingdom of Portugal as a sovereign state, independent of Spain and the Habsburg rulers of Spain.[38]

In some ways, then, Soveral and Almada had similar positions, working in difficult times to achieve peaceful diplomacy between Great Britain and Portugal, and both were largely successful. Soveral can't have known at the time that the 1890 Ultimatum may have been one of the important causes of the later downfall of the Portuguese monarchy.

Commentary on Soverol's Costume

[edit | edit source]

W. & D. Downey's portrait (above left) of Soveral shows a costume surprisingly — although not perfectly — accurate for its time. For some of its details, it can be compared to a 1634 portrait of Henri II of Lorraine, painted in 1634 by Anthony Van Dyck (right). Like the 1904 portrait of Don Antão Vaz de Almada, Van Dyck's portrait of Henri II is not the original of Soveral's costume. Van Dyck's painting was in Europe in the 1890s: "The painting was lent by Kay [Scottish collector Arthur Kay (c. 1862-1939), Esq., Glasgow[39]] to the 1893 Winter Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, London."[40] It seems to have been acquired by William Collins Whitney in 1900–1901, whose grandson Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney (1899–1992) gifted it to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[40]

Much of Soveral's costume seems to have been developed from portraits of cavaliers, like the Van Dyck portrait of Henri II, Duc de Guise (right) or the Van Dyck painting of cavaliers Lord John Stuart and his brother Lord Bernard Stuart. While most cavaliers appear feminized in contemporary portraits, Soveral's cavalier costume does not feminize him.

Although it has notable and interesting exceptions, Soveral's costume is unusually historically accurate.

- The ruff around Soveral's neck frames his face, while the large cavalier collar on Henri II of Lorraine puts the focus on the lovelock and the doublet. The drape of Henri's cavalier collar on his shoulders contrasts with the more squared shoulders in Soveral's costume. (Ruffs had gone out of fashion around 1630,[41]:334–336 and Soveral's costume is dated 1640.)

- The slashing on the sleeves of Soveral's doublet shows a satin lining instead of revealing the full sleeve of the undershirt the way the cavaliers' slashing would have. The edges of the slash have piping, similar to how they were piped on cavalier doublets.

- Soveral's shirt is not visible, classic of Victorian men's style, unlike the open doublet of the cavaliers.

- The piping around the slashing is repeated on the front and bottom edges of the doublet, the cloak, the belt and the hat. It is possible that the piping repeats also on the ribbon loops at the bottom of the breeches and on the boots, both at the top of the boots and on the straps for spurs.

- The button trim on the sleeves of the doublet and the outside seam of the breeches repeats the buttons used for the closure of the doublet.

- Soveral's doublet has a buttoned-up, Victorian look; some cavalier doublets buttoned down the front to the waist, but the look is looser and less formal. The fact that Soveral's doublet is unbuttoned below the waist shows an openness that is significantly more subtle than the suggestive decoration on the front Henri's breeches. The line of Soveral's doublet is fitted to the torso like a Victorian suit or frock coat.

- The doublet has a Victorian belt with eyelets and a prong.

- In the absence of information from any newspaper or eyewitness reporting, the many decorative buttons may be gold, silver, pearls or mother of pearl. Because some colors are very unreadable in black-and-white photography, they could be white or blue or some other color. He consistently wore black and white in his daily dress.

- Soveral is carrying his hat, which looks like it has a flat crown and a wide brim with a plume. Plumes were popular among the cavaliers (like the one on Henri's hat) as well as the Victorians (like the one on Soveral's).

- An honor of some kind is hanging around his neck on a ribbon instead of a chain. It may be two honors, one below the other. The top one may be the British Order of St Michael and St George, Honorary Knight Grand Cross, which he was awarded earlier that year, on 12 January 1897.

- The fabric used in the cape, doublet and breeches appears to be a silk velvet. A pattern in the fabric indicates a brocade weave.

- Soveral is wearing his cloak in the French style. Blanche Payne cites Kelly and Schwabe, Historic Costume: "Frenchmen preferred slinging it over the left shoulder and under the right arm ...; cords attached to the underside secured it firmly in place."[41]:336

- The two-color decorative cord with tassels is typical of the French style of that period (c. 1640).

- Soveral's white or light-colored gloves have gauntlets covered with white lace, very typical of Cavalier style.

- The cut of the breeches, which are fitted to the leg and wrinkled above the knees, are not similar to Cavalier breeches that were wide over the thighs and became narrower towards the knees.

- The band at the bottom of his breeches is made of loops of ribbon that may have piping at the edges. The loops of ribbons appear on portraits from the mid 17th century. Besides the portrait of Henri (above), this decorative element also appears at the bottom edge of the breeches in the portrait of Lord John Stuart, who is dressed in red and gold.

- Soveral's cloak shows behind his legs: his boots do not have cuffs.

- Soveral may be wearing hose, which may be visible between the bottom of the breeches and the top of the boots.

- In the Cavalier style the boots wrinkled at the ankles and they often had wide cuffs, although Soveral's boots in his portraits do not.

- Cavaliers wore spurs tied onto their boots with decorative straps like what Several is wearing on his boots, but he is not wearing spurs (presumably because dancing with spurs could damage valuable dresses).

Demographics

[edit | edit source]- Nationality: Portuguese

Family

[edit | edit source]- Eduardo Pinto de Soveral, 1st Viscount of São Luís[19]

- Maria da Piedade Paes de Sande e Castro[19]

- Luís Maria Augusto Pinto de Soveral, Marquês de Soveral (28 May 1851 – 5 October 1922)[19]

Also Known As

[edit | edit source]- Family name: de Soveral

- Marquis de Soveral (1900[7]:61–1922)

- Luís de Soveral

- Luís Maria Augusto Pinto de Soveral

- M. Luiz de Soveral

Notes and Questions

[edit | edit source]- De Soveral is #135 in the list of people who attended the Duchess of Devonshire's 2 July 1897 fancy-dress ball.

Biographies and Memoirs

[edit | edit source]- Lowndes Marques, Paulo. O Marquês de Soveral: seu tempo e seu modo [The Marquis of Soveral: His Time and His Manner or Style]. Lisbon: Editora Texto, 2009.

Footnotes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Martin, Ralph G. Lady Randolph Churchill : A Biography. Cardinal, 1974. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/ladyrandolphchur0002mart_w8p2/.

- ↑ "Alexandra of Denmark". Wikipedia. 2023-11-10. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alexandra_of_Denmark&oldid=1184410804. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandra_of_Denmark.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Ridley, Jane. The Heir Apparent: A Life of Edward VII, the Playboy Prince. Random House, 2013. Rpt of Bertie: A Life of Edward VII, 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Pless, Daisy, Princess of (Mary Theresa Olivia née Cornwallis-West). Princess Daisy of Pless by Herself. Ed. and Intro., Major Desmond Chapman-Huston. New York, Dutton, 1929.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tuchman, Barbara. The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War, 1890–1914. Random House, 2014 (Macmillan, 1962).

- ↑ Lee, Sidney, Sir. King Edward VII : A Biography. Macmillan, 1925. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/kingedwardviibio0002lees/.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 Brook-Shepherd, Gordon. Uncle of Europe: The Social and Diplomatic Life of Edward VII. London: Collins, 1975. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/uncleofeurope0000unse/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Macdonnell, Anne Lumb, Lady. Reminiscences of Diplomatic Life; Being Stray Memories of Personalities and Incidents Connected with Several European Courts and also with Life in South America Fifty Years Ago. Adam & Charles Black, 1913. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofd017823mbp/.

- ↑ "Fado". Wikipedia. 2023-10-20. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fado&oldid=1180971182. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fado.

- ↑ "Saudade". Wikipedia. 2023-10-30. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Saudade&oldid=1182616858. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saudade.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 "Luís Pinto de Soveral, Marquês de Soveral". Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. 2022-09-29. https://pt.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lu%C3%ADs_Pinto_de_Soveral,_Marqu%C3%AAs_de_Soveral&oldid=64484007. https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lu%C3%ADs_Pinto_de_Soveral,_Marqu%C3%AAs_de_Soveral.

- ↑ Ruffer, Jonathan Garnier. The Big Shots : Edwardian Shooting Parties. Debretts, Viking, 1977. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/bigshotsedwardia0000ruff/.

- ↑ Pless, Daisy, Princess. The Private Diaries of Daisy, Princess of Pless, 1873–1914. London: John Murray, 1950. [A "selection" from two of her earlier books.] Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/privatediariesof0000ples/.

- ↑ Pless, Daisy, Princess of (Mary Theresa Olivia née Cornwallis-West). Better Left Unsaid. Ed. and Intro., Desmond Chapman-Huston. E. P. Dutton, 1931. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/betterleftunsaid0000ples/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ridley, Jane. "The Marlborough House set (act. 1870s–1901)." Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 McLean, Roderick R. Royalty and Diplomacy in Europe, 1890-1914. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Leslie, Anita. The Marlborough House Set. Doubleday, 1973.

- ↑ "Charles Wynn-Carington, 1st Marquess of Lincolnshire". Wikipedia. 2015-07. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charles_Wynn-Carington,_1st_Marquess_of_Lincolnshire&oldid=970134784.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 "Luís Pinto de Soveral, 1st Marquis of Soveral". Wikipedia. 2020-09-02. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lu%C3%ADs_Pinto_de_Soveral,_1st_Marquis_of_Soveral&oldid=976400470.

- ↑ "Royal Victorian Order". Wikipedia. 2023-10-23. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Royal_Victorian_Order&oldid=1181536179. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Victorian_Order.

- ↑ "Military Order of the Tower and Sword". Wikipedia. 2023-06-15. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Military_Order_of_the_Tower_and_Sword&oldid=1160279778. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_Order_of_the_Tower_and_Sword.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "1890 British Ultimatum". Wikipedia. 2023-10-27. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=1890_British_Ultimatum&oldid=1182202990. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1890_British_Ultimatum.

- ↑ "The Grand Bal Poudre at Warwick Castle." Leamington Spa Courier 09 February 1895, Saturday: 6 [of 8], Cols. 1a–6c [of 6] – 7, Col. 1a. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000319/18950209/042/0006.

- ↑ "List of Vanity Fair (British magazine) caricatures (1895–1899)". Wikipedia. 2024-01-14. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_Vanity_Fair_(British_magazine)_caricatures_(1895%E2%80%931899)&oldid=1195518024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Vanity_Fair_(British_magazine)_caricatures_(1895%E2%80%931899).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Leslie, Anita. The Marlborough House Set. New York: Doubleday, 1973.

- ↑ "Edward VII". Wikipedia. 2023-10-22. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Edward_VII&oldid=1181312160. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_VII.

- ↑ "Ambassador". Wikipedia. 2023-10-02. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ambassador&oldid=1178216856. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambassador#Ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary.

- ↑ "Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907". Wikipedia. 2023-10-07. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hague_Conventions_of_1899_and_1907&oldid=1179091516. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hague_Conventions_of_1899_and_1907#1907.

- ↑ "Fancy Dress Ball at Devonshire House." Morning Post Saturday 3 July 1897: 7 [of 12], Col. 4a–8 Col. 2b. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000174/18970703/054/0007.

- ↑ "Devonshire House Fancy Dress Ball (1897): photogravures by Walker & Boutall after various photographers." 1899. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait-list.php?set=515.

- ↑ "Luis Maria Augusto Pinto de Soveral, Marquess de Soveral as Count d'Almada, A.D. 1640." Diamond Jubilee Fancy Dress Ball. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw158382/Luis-Maria-Augusto-Pinto-de-Soveral-Marquess-de-Soveral-as-Count-dAlmada-AD-1640.

- ↑ Melo, Artur Napoleão Vieira de (1904), English: Retrospective portrait of Antão Vaz de Almada (c. 1573–1644), by Artur de Melo, 1904. In the collection of the Lisbon Military Museum, Portugal., retrieved 2022-01-26. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D._Antão_Vaz_de_Almada_(1904)_-_Artur_de_Melo_(Museu_Militar_de_Lisboa).png.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Antão de Almada, 7th Count of Avranches". Wikipedia. 2023-11-03. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ant%C3%A3o_de_Almada,_7th_Count_of_Avranches&oldid=1183340619. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ant%C3%A3o_de_Almada,_7th_Count_of_Avranches.

- ↑ "Count of Almada". Wikipedia. 2023-09-20. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Count_of_Almada&oldid=1176301942. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Count_of_Almada.

- ↑ "Antão de Almada, 7.º conde de Avranches". Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. 2023-10-09. https://pt.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ant%C3%A3o_de_Almada,_7.%C2%BA_conde_de_Avranches&oldid=66741097. https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ant%C3%A3o_de_Almada,_7.%C2%BA_conde_de_Avranches. Translated by Google Translate.

- ↑ "Portuguese Restoration War". Wikipedia. 2022-01-24. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Portuguese_Restoration_War&oldid=1067637666. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_Restoration_War.

- ↑ "Charles I of England". Wikipedia. 2023-12-12. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charles_I_of_England&oldid=1189605401. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_I_of_England.

- ↑ "Antão de Almada, 7.º conde de Avranches". Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. 2023-10-09. https://pt.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ant%C3%A3o_de_Almada,_7.%C2%BA_conde_de_Avranches&oldid=66741097. https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ant%C3%A3o_de_Almada,_7.%C2%BA_conde_de_Avranches.

- ↑ "Biography." "Provenance". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-20. https://www.nga.gov/collection/provenance-info.28576.html#biography

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Provenance." Dyck, Sir Anthony van (c. 1634), Henri II de Lorraine, retrieved 2023-12-20. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.34046.html#provenance.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Payne, Blanche. History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century. Harper & Row, 1965.