WikiJournal of Science/Paranthodon

WikiJournal of Science

Open access • Publication charge free • Public peer review • Wikipedia-integrated

Previous

Volume 1(1)

Volume 1(2)

Volume 2(1)

Volume 3(1)

Volume 4(1)

Volume 5(1)

Volume 6(1)

This article has been through public peer review.

It was adapted from the Wikipedia page Paranthodon and contains some or all of that page's content licensed under a CC BY-SA license. Post-publication review comments or direct edits can be left at the version as it appears on Wikipedia.

First submitted:

Accepted:

Reviewer comments

PDF: Download

DOI: 10.15347/wjs/2020.001

QID: Q83852037

XML: Download

Share article

![]() Email

|

Email

| ![]() Facebook

|

Facebook

| ![]() Twitter

|

Twitter

| ![]() LinkedIn

|

LinkedIn

| ![]() Mendeley

|

Mendeley

| ![]() ResearchGate

ResearchGate

Suggested citation format:

Iain Reid (2020). "Paranthodon". WikiJournal of Science 3 (1): 1. doi:10.15347/WJS/2020.001. Wikidata Q83852037. ISSN 2470-6345. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikiversity/en/6/6b/Paranthodon.pdf.

Citation metrics

AltMetrics

Page views on Wikipedia

Wikipedia: This work is adapted from the Wikipedia article Paranthodon (CC BY-SA). Content has also subsequently been used to update that same Wikipedia article Paranthodon.

License: ![]()

![]() This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are credited.

Thijs van Vlijmen ![]() (handling editor) contact

(handling editor) contact

Jack Nunn ![]() (handling editor) contact

(handling editor) contact

David J Button ![]()

Niclas Borinder

Article information

Abstract

Paranthodon (/pəˈrænθədɒn/) is a genus of extinct stegosaurian dinosaur that lived in South Africa during the Early Cretaceous, between 139 and 131 million years ago. Discovered in 1845, it was one of the first stegosaurians found. Its only remains, a partial skull and isolated teeth, were found in the Kirkwood Formation. British paleontologist Richard Owen initially identified the fragments as those of the pareiasaur Anthodon. After remaining untouched for years in the British Museum of Natural History, the partial skull was identified by South African paleontologist Robert Broom as belonging to a different genus; he named the specimen Palaeoscincus africanus. Several years later, Hungarian paleontologist Franz Nopcsa, unaware of Broom's new name, similarly concluded that it represented a new taxon, and named it Paranthodon owenii. Since Nopcsa's species name was assigned after Broom's, and Broom did not assign a new genus, both names are now synonyms of the current binomial, Paranthodon africanus. The genus name combines the Ancient Greek para (near) with the genus name Anthodon, to represent the initial referral of the remains.

In identifying the remains as those of Palaeoscincus, Broom initially classified Paranthodon as an ankylosaurian, a statement backed by the research of Coombs in the 1970s. However, in 1929, Nopcsa identified the taxon as a stegosaurid, with which most modern studies agree. In 1981, the genus was reviewed with modern taxonomy, and found to be a valid genus of stegosaurid. However, a 2018 review of Paranthodon could only identify one distinguishing feature, and while that study still referred it to Stegosauria based on similarity and multiple phylogenetic analyses, no diagnostic features of the group could be identified in Paranthodon.

History of discovery

In 1845, amateur geologists William Guybon Atherstone and Andrew Geddes Bain discovered several fossils near Dassieklip, Cape Province, in the Bushmans River Valley.[1][2] This was the first dinosaur find in all of the Southern Hemisphere and Africa.[3] In 1849 and 1853, Bain sent some of the fossils to Richard Owen for identification. Among them was an upper jaw Bain referred to as the "Cape Iguanodon", so the site was named "Iguanodonhoek". Atherstone published a short paper about the discovery in 1857,[1] but lamented in 1871 that it had thus far received no attention in London.[2][4] Only in 1876 were a series of specimens from the collection named by Owen as Anthodon serrarius, basing the generic name on the resemblance of the teeth to a flower.[5] The partial holotype skull BMNH 47337, the left jaw BMNH 47338, the matrix BMNH 47338 including bone fragments and impressions of the anterior skull, and the vertebrae BMNH 47337a were all assigned to Anthodon.[6] In 1882, Othniel Charles Marsh assigned Anthodon to Stegosauridae based on BMNH 47338, and in 1890, Richard Lydekker found that although Anthodon was a pareiasaur, its teeth were similar to those of the Stegosauridae.[6] Lydekker in 1890 also corrected a mistake of Owen, who had incorrectly summarized all the material as coming from a single locality, whereas there was separate material from two clearly distinct localities.[2]

In 1909, Robert Broom visited the collection of the British Museum of Natural History. He concluded that Owen had mixed the partial distorted skull, teeth, and a mandible of a pareiasaur and a partial upper jaw of a dinosaur, BMNH 47338, which were actually from two different species.[5][7] Broom kept the name Anthodon for the pareiasaur, but identified the other fossil as a member of the genus Palaeoscincus, naming the new species Paleoscincus africanus in 1912. He found that the anatomy of the teeth were quite different, even though they resembled each other, as well as those of Stegosaurus.[2][7] In 1929, Franz Nopcsa, unaware of Broom's previous publication, provided a second novel name as D.M.S. Watson believed that the jaw should be differentiated from Anthodon.[2][8] Nopcsa named the species Paranthodon Owenii, with the generic name derived from the Latin para, meaning "similar", "near", or "beside", and Anthodon, and specific name honoring Owen.[8][9][10] Per to present conventions, the specific name was later emended to owenii.[6] Both names were brought into the current nomenclature by Walter P. Coombs in his 1971 dissertation as the new combination Paranthodon africanus, as the name Paranthodon was the first new generic name for the fossils and africanus was the first new specific name.[2][11] This makes Paranthodon africanus the proper name for the taxon previously known as Palaeoscincus africanus and Paranthodon owenii.[2][6]

Material

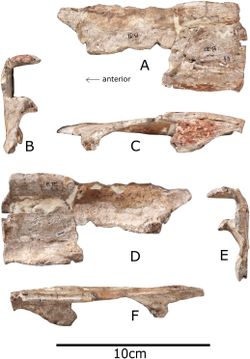

Thomas Raven & Susannah Maidment, CC-BY 4.0

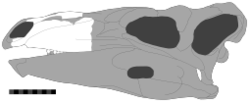

The holotype of Paranthodon, BMNH 47338, was found in a layer of the Kirkwood Formation that has been dated between the Berriasian and early Valanginian ages. It consists of the back of the snout, containing the maxilla with teeth, the posterior caudodorsal ramus of the premaxilla, part of the nasals, and some isolated teeth probably from the lower jaw. One additional specimen was assigned to it based on the dentition, BMNH (now NHMUK) R4992, including only isolated teeth sharing the same morphology as those from the holotype.[6] Some bones that were unidentified by the review of Galton & Coombs (1981) were described as a fragment of a vertebra in 2018 by Raven & Maidment.[12] However, the teeth do not bear any autapomorphies of Paranthodon and were referred to an indeterminate stegosaurid in 2008.[13] The teeth were identified in 2018 as also lacking any distinct stegosaurian features, and were thus designated as indeterminate Thyreophora.[12]

The Mugher Mudstone Formation of Ethiopia was screened in the 1990s by the University of California Museum of Paleontology, and in it were discovered multiple dinosaur teeth, pertaining to many groups of taxa. The locality has been described as "the largest and most complete record of dinosaur fossils from a Late Jurassic African locality outside of Tendaguru" by Lee Hall.[14] Two of the partial teeth discovered were referred to Paranthodon by Hall and Mark Goodwin in 2011. However, the reasons for the referral to Paranthodon were not discussed.[14]

Description

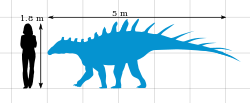

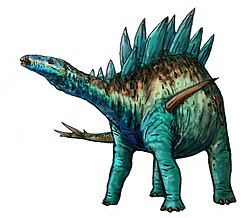

Paranthodon was a small relative of larger stegosaurids such as Stegosaurus. Thomas R. Holtz Jr. estimated that the animal was 5.0 m (16.4 ft) long and weighed between 454 and 907 kg (1,001 and 2,000 lb).[9][15] The snout is elongated, though not extremely so, and convex on top. The back of the premaxilla is long and broad, and the external nares are large. The teeth have a prominent primary ridge. The fossilized nasal and maxillary bones are relatively complete, and an incomplete premaxilla is also preserved. The partial snout resembles Stegosaurus in its large posterior premaxillary process and the extension of the palate. However, Stegosaurus was the only stegosaurid known from adequate cranial material to compare with Paranthodon during the 1981 review of the taxon, and even though their resemblance is great, tooth morphology is very distinguishing among the stegosaurians. For example, cranial material is known from Stegosaurus, Paranthodon, Kentrosaurus, and Tuojiangosaurus, and the tooth morphology differs in all of them.[6][12]

The premaxilla of Paranthodon is incomplete, but the anterior process is sinuous and curves ventrally. This is similar to in Miragaia, Huayangosaurus, the ankylosaur Silvisaurus, and Heterodontosaurus, but unlike in Chungkingosaurus, Stegosaurus, Edmontonia and Lesothosaurus. The premaxilla also lacks any teeth, like in every stegosaur except Huayangosaurus where the premaxilla is preserved. Like in Huayangosaurus but not Stegosaurus or Hesperosaurus, the nasal fenestra faces anterolaterally, being visible from the front and sides. The naris is longer than wide like in other stegosaurs, and also has a smooth internal surface, so it was most likely a simple passage.[12] The maxilla is roughly triangular, as in most other thyreophorans. The tooth row is horizontal in lateral view, and in ventral view it is sinuous. Stegosaurus and Huayangosaurus possess a straight tooth row in ventral view, although Scelidosaurus and Jiangjunosaurus do not.[12] The maxilla of Paranthodon preserves the tooth row, and shows that there is little to no overhang. This differs from ankylosaurians, where there is a large amount of overhang of the maxilla.[16] Like in Stegosaurus and Silvisaurus there is a diastema (gap in the tooth row) on the maxilla in front of the tooth row. The posterior maxilla is incomplete so there is no information known about the jugal or lacrimal contact.[12] Paranthodon has an elongate, dorsally convex nasal, like in most other stegosaurs. There are thickened ridges along the sides of the nasals. The preserved portion of the nasal does not contact the premaxilla or maxilla.[12]

Thomas Raven & Susannah Maidment, CC-BY 4.0

13 teeth are preserved in Paranthodon, but as they extend to the back of the maxilla there were possibly more in life. The teeth are symmetrical as in stegosaurs except Chungkingosaurus. Along the base of the tooth crown there is a swelling (cingulum), which is seen in all other stegosaurs from teeth are known, except Huayangosaurus.[12] The teeth have a middle ridge, with five fewer prominent ridges on either side. This is similar to the size ridges seen on Kentrosaurus.[16] Like all stegosaurians, the denticles on the teeth are rounded at the tips, in contrast to ankylosaurians. Also, like Huayangosaurus, but unlike Kentrosaurus and Stegosaurus, Paranthodon possesses a prominent buccal margination (a ridge beside the tooth row). Paranthodon teeth preserve wear, but wear is absent on most teeth, similar to Huayangosaurus, meaning it is likely that Paranthodon lacked occlusion between teeth.[17]

As only two fragments of a vertebra are known, little anatomical details can be observed. The right transverse process and prezygapophysis are preserved. The vertebra is possibly a middle dorsal, based on the angle of the transverse process and the orientation of the prezygapophysis. Similar to Stegosaurus and Chungkingosaurus mid-dorsals, the transverse process is angled about 60º dorsally. Unlike in all other stegosaurs except Stegosaurus, the prezygapophysis faces dorsally.[12]

Classification

Currently, Paranthodon is classified as a stegosaur related to Stegosaurus, Tuojiangosaurus, and Loricatosaurus. Initially, when Broom assigned the name Palaeoscincus africanus to the Paranthodon fossils, he classified them as an ankylosaurian. This classification was later changed by Nopcsa, who found that Paranthodon best resembled a stegosaurid (before the group was truly defined[18]). Coombs (1978) did not follow Nopcsa's classification, keeping Paranthodon as an ankylosaurian, like Broom, although he only classified it as Ankylosauria incertae sedis.[19] A subsequent review by Galton and Coombs in 1981 instead confirmed Nopcsa's interpretation, redescribing Paranthodon as a stegosaurid from the Late Cretaceous.[6][16] Paranthodon was distinguished from other stegosaurs by a long, wide, posterior process of the premaxilla, teeth in the maxilla with a very large cingulum, and large ridges on the tooth crowns.[10] Not all of these features were considered valid in a 2008 review of Stegosauria, with the only autapomorphy found being the possession of a partial second bony palate on the maxilla.[13]

Multiple phylogenetic analyses have placed Paranthodon in Stegosauria, and often in Stegosauridae. A 2010 analysis including nearly all species of stegosaurians found that Paranthodon was outside Stegosauridae, and in a polytomy with Tuojiangosaurus, Huayangosaurus, Chungkingosaurus, Jiangjunosaurus, and Gigantspinosaurus. However, when the latter two genera were removed, Paranthodon grouped with Tuojiangosaurus just outside Stegosauridae, and Huayangosaurus grouped with Chungkingosaurus in Huayangosauridae.[20] An elaboration upon this analysis was published in 2017 by Susannah Maidment and Thomas Raven, which achieved much greater resolution of the relationships inside Stegosauria. Nearly all described stegosaur taxa were included, and Paranthodon grouped with Tuojiangosaurus, Huayangosaurus and Chunkingosaurus as the most basal true stegosaurians. However, the position of Alcovasaurus was uncertain, and further work could yield different results, with the phylogeny vulnerable to changes in taxon sampling. Below is the single most parsmonious tree recovered from analysis of a combined dataset of discrete and continuous characters in that study.[21]

| Thyreophora |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other analyses have found Paranthodon closely related to Tuojiangosaurus, Loricatosaurus, and Kentrosaurus within Stegosaurinae.[13][22] Even though phylogenetic analyses recognize Paranthodon as a stegosaurid, the type material actually bears no synapomorphies of Stegosauria. However, the material is very likely representative of the group, with phylogenetic analyses performed in separate studies by separate authors having resolved it as a stegosaurian.[20][12]

Paleoecology

As a stegosaur, Paranthodon would have been a slow-moving, mid-level quadrupedal browser that defended itself using a tail with spines on it.[23]

The Kirkwood Formation is in South Africa, and many fossils of different species and genera have been discovered in it, with Paranthodon being the first uncovered.[24] The formation is of a Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous age, with the oldest deposits from the Tithonian, about 145.5 million years ago, and the youngest rocks being from the Valanginian, about 130 million years ago.[9][10][25] The specific vertebrate-bearing portion of the formation is approximately level with the upper region of the Sundays River Formation, which has been dated to 139 to 131 mya based on microfossils.[26] A large variety of different animal groups have been found in the formation, including dinosaurs, at least two different sphenodontian lizards, multiple teleost fishes, a few crocodylians, some frog specimens, and also turtles. However, a large amount of the material of the Kirkwood formation only includes isolated teeth or partial and fragmentary pieces of bone. Dinosaurs of the formation include a basal tetanuran, the primitive ornithomimosaurian Nqwebasaurus, the sauropod Algoasaurus, a potential titanosaur, many ornithischians, Paranthodon, a genus of iguanodontian, and a "hypsilophodontid" (the family Hypsilophodontidae is no longer considered to be a natural grouping[27]).[24][28] Multiple additional sauropod taxa have been discovered in the Kirkwood deposits, including a basal eusauropod, a brachiosaurid, a dicraeosaurid and a derived diplodocid.[26]

If the referral of teeth from Ethiopia to Paranthodon is correct, then the taxons geographic range is extended significantly. The Mugher locality is approximately 151 million years old, about 14 million older than has previously been suggested for Paranthodon, as well as across both southern and eastern Africa. The fauna in the Mugher locality differ from elsewhere of the same time and place in Africa. While the Tendaguru has abundant stegosaurs, sauropods, ornithopods and theropods, the Mugher Mudstone preserves the stegosaur Paranthodon, a hypsilophodontid ornithopod, a probably sauropod, and theropods referred to Allosauridae and Dromaeosauridae.[14]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the many Wikipedia editors who assisted with writing, editing, contributing images to, or otherwise helping to improve the article on Paranthodon, especially those who participated at the Dinosaur image accuracy review, Wikipedia good article review, and the Wikipedia features article review: FunkMonk, Dank, Jimfbleak, Casliber, MWAK, Firsfron, Raptormimus458 and PaleoGeekSquared.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Atherstone, W.G. (1857). "Geology of Uitenhage". The Eastern Province Monthly Magazine 1 (10): 518–532.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 de Klerk, W.J. (2000). "South Africa's first dinosaur revisited - history of the discovery of the stegosaur Paranthodon africanus (Broom)". Annals of the Eastern Cape Museums 1: 54–60. ISSN 1562-5273. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/51874772#page/55/mode/1up.

- ↑ Durand, J.F. (2005). "Major African contributions to Palaeozoic and Mesozoic vertebrate palaeontology". Journal of African Earth Sciences 43 (2005): 71. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.07.014.

- ↑ Atherstone, W.G. (1871). "From Graham’s Town to the Gouph". Selected articles from the Cape Monthly Magazine (New Series 1870-76). Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Owen, R. (1876). Descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the collection of the British Museum. Order of the Trustees. pp. 14–15. https://books.google.com/books?id=BWJYAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Galton, P.M.; Coombs, W.P. Jr. (1981). "Paranthodon africanus (broom) a stegosaurian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of South Africa". Geobios 14 (3): 299–309. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(81)80177-5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Broom, R. (1912). "Observations on some specimens of South African fossil reptiles preserved in the British Museum". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 2: 19–25. doi:10.1080/00359191009519357.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nopsca, F. (1929). "Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenburgen V. Geologica Hungarica. Series Palaeontologica". Fasciculus 4 (1): 13.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Holtz, T.R. Jr. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House Books. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-375-92419-4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Glut, D.F. (1997). Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia. McFarland & Co.. pp. 676–677. ISBN 978-0-7864-7222-2.

- ↑ Olshevsky, G. (1978). "The Archosaurian Taxa (excluding the Crocodylia)". Mesozoic Meanderings (GAT Enterprises) (1): 1–50.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 Raven, T.J.; Maidment, S.C.R. (2018). "The systematic position of the enigmatic thyreophoran dinosaur Paranthodon africanus, and the use of basal exemplifiers in phylogenetic analysis". PeerJ 6: e4529. doi:10.7717/peerj.4529.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Maidment, S.C.R.; Norman, D.B.; Barrett, P.M.; Upchurch, P. (2008). "Systematics and Phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6 (4): 367–407. doi:10.1017/S1477201908002459.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Hall, L.E.; Goodwin, M.B. (2011). "A diverse dinosaur tooth assemblage from the Upper Jurassic of Ethiopia: implications for Gondwanan dinosaur biogeography". Las Vegas, Nevada, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3740.7763. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lee_Hall4/publication/291344526_A_DIVERSE_DINOSAUR_TOOTH_ASSEMBLAGE_FROM_THE_UPPER_JURASSIC_OF_ETHIOPIA_IMPLICATIONS_FOR_GONDWANAN_DINOSAUR_BIOGEOGRAPHY/links/56a1047d08ae2afab882814a/A-DIVERSE-DINOSAUR-TOOTH-ASSEMBLAGE-FROM-THE-UPPER-JURASSIC-OF-ETHIOPIA-IMPLICATIONS-FOR-GONDWANAN-DINOSAUR-BIOGEOGRAPHY.pdf.

- ↑ Holtz, T.R. Jr. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages". University of Maryland. Retrieved 2014-09-05.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Galton, P.M. (1981). "Craterosaurus pottonensis Seeley, a stegosaurian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of England, and a review of Cretaceous stegosaurs". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie 161 (1): 28–46. ISSN 0077-7749.

- ↑ Barrett, P.M. (2001). "Tooth Wear and Possible Jaw Action of Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen and a Review of Feeding Mechanisms of Other Thyreophoran Dinosaurs". In Carpenter, Kenneth. The Armoured Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 36–39. ISBN 0-253-33964-2. https://books.google.com/?id=04tQ5_qJN8MC.

- ↑ Sereno, P.C. (2005). "Stegosauridae". TaxonSearch: Database for Suprageneric Taxa & Phylogenetic Definitions. Archived from the original on 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

- ↑ Coombs, W.P. Jr. (1978). "The Families of the Ornithischian Dinosaur Order Ankylosauria". Palaeontology 21 (1): 143–170. http://cdn.palass.org/publications/palaeontology/volume_21/pdf/vol21_part1_pp143-170.pdf.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Maidment, S.C.R. (2010). "Stegosauria: a historical review of the body fossil record and phylogenetic relationships". Swiss Journal of Geological Sciences 103 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0023-3. ISSN 1661-8726. https://www.academia.edu/1477959/Stegosauria_A_review_of_the_body_fossil_record_and_phylogenetic_relationships.

- ↑ Raven, T.j.; Maidment, S.C.R. (2017). "A new phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)". Palaeontology 2017: 1–8. doi:10.1111/pala.12291.

- ↑ Galton, P.M. (2012). "Stegosauria". In Brett-Surman, Michael; Holtz, Thomas R. Jr.; Farlow, James O.. The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press. p. 486. ISBN 978-0-253-00849-7. https://books.google.com/?id=pX_l24sDARwC.

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2 ed.). Indiana University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Forster, C.A.; Farke, A.A.; McCartney, J.A.; de Klerk, W.J.; Ross, C.F. (2009). "A "Basal" Tetanuran from the Lower Cretaceous Kirkwood Formation of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (1): 283–285. doi:10.1671/039.029.0101.

- ↑ Pereda Suberbiola, X.; Galton, P.M.; Torcida, F.; Huerta, P.; Izquierdo, L.A.; Montero, D.; Pérez, G.; Urién, V. (2003). "First stegosaurian dinosaur remains from the Early Cretaceous of Burgos (Spain), with a review of Cretaceous stegosaurs". Revista Espanola de Paleontologia 18 (2): 143–150. doi:10.7203/sjp.18.2.21640. ISSN 0213-6937.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 McPhee, B.W.; Mannion, P.D.; de Klerk, W.J.; Choiniere, J.N. (2016). "High diversity in the sauropod dinosaur fauna of the Lower Cretaceous Kirkwood Formation of South Africa: Implications for the JurassiceCretaceous transition". Cretaceous Research 59 (2016): 228–248. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.11.006.

- ↑ Brown, C. M.; Evans, D. C.; Ryan, M. J.; Russell, A. P. (2013). "New data on the diversity and abundance of small-bodied ornithopods (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Belly River Group (Campanian) of Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33 (3): 495. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.746229.

- ↑ Chinsamy, A. (1997). "Albany Museum, Grahamstown, South Africa". In Currie, P.J.; Padian, K.. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.