Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Motivated reasoning

What is motivated reasoning and how does it affect our lives?

Overview

[edit | edit source]| “ | ... motivation can be construed as affecting the process of reasoning: forming impressions, determining one's beliefs and attitudes, evaluating evidence, and making decisions. | ” |

| — Kunda, 1990, p. 480 | ||

Human beings are not always rational and smart.[1] People often construct, evaluate, and draw conclusions that reflect biased or motivated reasoning. Information that is inconsistent with biases or preferences are more severely criticised. However, if the information agrees or is inline with prior beliefs, the same people relax those critical standards and find further facts or opinions that support these conclusions. This is known as motivated reasoning.

|

Michael and Tim are watching a game of football together. Each of them go for opposing teams and are convinced that the referees are biased against their team. Tim’s team is playing poorly, even though up until this game they’ve been on a winning streak. Tim therefore attributes the good performance of Michael’s team to good luck rather than skill. Tim is also highly motivated to find reasons why the referee is wrong in valid calls against his own team and criticises them, yet when there are fouls against Michael’s team, Tim is more than happy to call it fair and not examine it too closely. In this example, we can say that Tim’s reasoning is strongly influenced by which side he wants to win.

|

Evidence for motivated reasoning shows that it effects perception, attitudes, and attributions[2] which have vast impacts on many areas of our daily lives; not only ordinary things like sports, but health, relationships, politics, science, and even what we may consider fair or ethical views, are affected by our motivations. Paired together with confirmation bias to alleviate cognitive dissonance, motivated reasoning allows people to believe biased conclusions even if there is contrary evidence or information.[1] The study of motivated reasoning is therefore important; to understand why people make decisions we must look at their motivated reasoning. If we understand this then it may be easier to change one's mind and lifestyle, through smarter and more rational decisions.

This chapter will cover:

- What motivated reasoning is

- Mechanisms of motivated reasoning

- Cognitive dissonance and biases

- Effects of motivated reasoning on our lives

- Limiting motivated reasoning to create pathways to rational thinking

|

Focus questions:

|

What is motivated reasoning?

[edit | edit source]| “ | For a man always believes more readily that which he prefers. | ” |

| — Francis Bacon, 1620/1955, p. 111 | ||

People’s preferences are often reflected in their beliefs and attitudes – “people believe what they want to believe”.[1] However, reasoning is not as simple as this saying. Reasoning can be influenced, sometimes subtly, by motivations that contribute to biased beliefs thought to be true (illusion of objectivity). Thus, while believing to be rational, people using motivated reasoning, to reach a particular outcome or conclusion, attempt to construct justifications, and avoid contradictions, to attain the evidence necessary to support it.[2]

To further understand what creates motivated reasoning, we can explore its components: motivation and reasoning.

Motivation

[edit | edit source]Motivation has been a central and recurrent topic in the field of psychology. Understanding its consequences is important in areas such as labour, education, health, and parenting. [3]

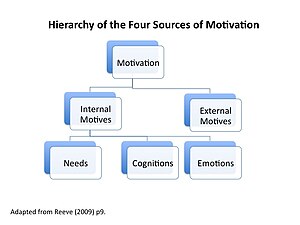

Motivation is any wish, desire, or preference – it is the wanting of change or a desired outcome, whether conscious or not, that is shaped by cognition, emotion, and needs. [2][4] It is also an internal process that energises, directs, and sustains behaviour, [5] and can be either intrinsic or extrinsic (see table 1).

Intrinsic motivation

[edit | edit source]Intrinsic motivation refers to an individual’s behaviour that is driven by the value of an activity. This activity has value as it extends or applies one’s abilities, contains exploration or learning, or seeks out novelty and challenge.[3] Intrinsic motivation is essential to cognitive and social development, and acts as a source of fulfilment or satisfaction.

Extrinsic motivation

[edit | edit source]Extrinsic motivation contracts with intrinsic motivation in that it is the undertaking of an activity in order to receive an external outcome, and uses agency rather than the enjoyment of the actual activity. Extrinsic motivation also involves intentional behaviour but can vary in an individual’s autonomy, such as doing an activity knowing it will benefit you in the long wrong or complying to an activity with external forces.[3]

Table 1. Types of motivation (adapted from motivation table based on Self-Determination Theory from Ryan & Deci, 2000).

| Motivation Type | Intrinsic | Extrinsic |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation source | Internal source of motivation | External source of motivation |

| Types of motivators | Sense of achievement

Curiosity Interest Pride Mastery Exploration Autonomy Competence |

Money and bonuses

Grades Praise Career advancements School grades Avoid punishment Future benefits Recognition |

| Example behaviour | I will study for this exam because I enjoy the content and

learning makes me feel a sense of achievement. |

I will study for this exam because if I don't I will receive a

bad grade or my parents will ground me. |

However, motivation behind motivated reasoning can sometimes get confusing. In motivated reasoning, the goal or conclusion is motivated and changes the reasoning or cognition behind perceptions; such as the assessment and credibility of evidence, and the construction and evaluation of arguments. People are motivated to arrive at a preferred conclusion.[2] This is often done as a way to avoid or decrease cognitive dissonance that people experience when challenged by inconsistent information – rather than thinking critically about the information, individuals often favour dismissal or seek justifications that support their view.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations can also influence motivated reasoning, and are often behind conscious perceptions and attitudes (see the below case study).

|

Politicians are in no way immune to motivated reasoning – you could even say that with all the information politicians are confronted with, it would be hard for them to make informed decisions and avoid biased preferences. Yet, politicians are expected to hold higher standards and more factual knowledge than ordinary citizens (Baekgaard, et al., 2017). Yet, parliamentary member John Johnson denies global warming from human pollution even though there is substantial amounts of evidence to the contrary. Instead, Johnson has been caught on record to say it’s caused by methane from cows. Johnson has also received over $2 million in campaign contributions from oil and gas companies. In this example, the motivated reasoning is that Johnson reasons towards the conclusion that humans don’t cause global warming, despite evidence that supports the opposite, because he is making money off of the oil and gas companies (extrinsically motivated). |

Reasoning

[edit | edit source]| “ | Reasoning can be used for a variety of purposes: to deceive, to argue, to debate, to doubt, to persuade, to express, to explain, to apologise, to rationalise, etc. | ” |

| — Peter A. Angeles, 1981, as cited in Evans, 1993, p. 402 | ||

Reasoning is a cognitive process and the central activity in intelligent thinking, through which knowledge and experience is applied to make decisions, solve problems, and draw conclusions. [6] Reasoning is a central focus in psychology and philosophy with implications for improving critical thinking in a variety of disciplines, such as education, science, and law. In psychology, reasoning is studied by observing at how people reason, which cognitive processes are involved, and how the reasoning is influenced. There are several different types of reasoning, such as; inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning, and abductive reasoning (see table 2). Other types of reasoning, such as those explained by Walton (1990)[7], include theoretical reasoning and practical reasoning.

Table 2.

Types of reasoning. Source: Reasoning - Psychology Wiki

| Reasoning Type | Inductive reasoning | Deductive reasoning | Abductive reasoning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | The process in drawing general conclusions from specific observations and evidence. These conclusions form the basis of an argument that may not be true but are most

probable.

|

The process of determining whether a conclusion logically follows from statements and is just as certain as the premises. The statement can't be true if the conclusion is false, as the reasoning is intended to prove a specific conclusion.

|

The process of choosing the likeliest explanation based on an incomplete set of observations and often involves both inductive and deductive reasoning. This type of reasoning attempts to favour one conclusion over another, by either dismissing alternative explanations or demonstrating the probability of the preferred choice. |

| Examples | Observation: The ball I pulled from the bag is blue. The second ball I get is also blue and so is the third.

Conclusion: All balls are blue. |

Premise 1: All humans eat food

Premise 2: Lucy is a human Conclusion: Therefore, Lucy eats food |

Premise 1: The bank robber on TV has black hair, blue eyes, and is wearing a pink hat.

Premise 2: Your friend has blue eyes and is wearing a pink hat. Conclusion: Your friend is the bank robber. |

While reasoning often involves the use of logic in order to create valid arguments, cognitive biases and emotions can significantly interfere with behaviours, beliefs, or attitudes.

Mechanisms of motivated reasoning

[edit | edit source]| “ | Once a man’s understanding has settled on something (either because it is an accepted belief or because it pleases him), it draws everything else also to support and agree with it. And if it encounters a larger number of more powerful countervailing examples, it either fails to notice them, or disregards them, or makes fine distinctions to dismiss and reject them, and all this with much dangerous prejudice, to preserve the authority of its first conceptions | ” |

| — Francis Bacon 1620/2000, as cited in Carpenter, 2019, p. 1 | ||

One of the difficulties in understanding motivated reasoning is that people have many different goals, beliefs, expectations, and attitudes that affect their reasoning and judgement. As such, the critical process of gathering information and evaluating it during reasoning can be guided by these influences. There are two main mechanisms of motivated reasoning, or competing motivates, as proposed by Kunda (1990)[2]; one in which the motive is to arrive at an accurate conclusion (accuracy goals); and the other in which the motive is to arrive at a specific, directional conclusion (directional goals). However, Nawara (2015)[8] proposes that motivated reasoning occurs when directional goals bias reasoning and is supported by Kahan (2013)[9] who defines motivated reasoning as people conforming to information if it confirms their conclusions extrinsic to accuracy.

Reasoning driven by accuracy goals

[edit | edit source]Individuals driven by accuracy goals are motivated to reach impartially true conclusions that considers all the evidence, regardless of the implications. [1][10] Informed decisions are made based on the relevant evidence.

When individuals are motivated to be accurate, processes of information gathering and evaluation involve more complex and time-consuming decision-making strategies.[2] This may be due to accuracy goals typically being created with higher stakes involved, such as more severe consequences for making the wrong judgement or conclusion, or individuals are required to justify their reasoning publicly. These higher stakes lead to more careful cognitive processing and a reduction of cognitive biases.[2]

However, people tend to have an easier time finding evidence that supports what they want to believe over evidence supporting what they want to be false, even if they are not actively avoiding information. This can lead to failure in recognising biases in their information search and assessment, leaving people feeling that their belief is firmly supported by the applicable evidence they have found, and thus have an illusion of objectivity.[1]

Reasoning driven by directional goals

[edit | edit source]Reasoning driven by directional goals is the main classification of motivated reasoning in which cognitive biases lead to the dismissal or avoidance of inconsistent information that doesn’t agree with a specific and preselected conclusion or preference.[10] Individuals driven by directional motivated reasoning use reasoning strategies that facilitate engagement with their own prior attitudes and beliefs to fit in accordance with the information presented. Decision making also tends to be more rapid, intuitive, and emotional. Why are people so inclined to be driven by directional goals rather than reasoning that could be based on accuracy? Dawson and colleagues (2002)[11] suggest that individuals seek to draw conclusions that provide positive outcomes for themselves; support prior beliefs and attitudes; and demonstrate their success and well-being; all while maintaining an illusion of objectivity to themselves and others.

Gilovich (1991, as cited in Epley & Gilovich, 2016)[1] proposed that when motivated reasoning occurs, individuals ask themselves two questions depending on the proposition of information; “must I believe this?”, and “can I believe this?”. People ask the ‘must I?’ question when challenged with information they would prefer not to be true, and thus invoke a more rigorous standard on the evidence. This typically leads to more flaws or limitations being found and therefore, people are more motivated to reject the information as they have found a genuine reason to do so.[11] The ‘can I?’ question refers to an individual being able to believe information for even the most uncertain of beliefs, such as support for crazy conspiracy theories.[1] Critical standards are much less stringent and superficial, and biases are involved when searching for evidence that supports a particular conclusion.[11]

Cognitive dissonance also may explain why motivational reasoning occurs. Carpenter (2019)[12] proposes that information that is highly inconsistent with one’s own beliefs or attitudes, especially from a highly credible source, would likely produce cognitive dissonance. Motivated reasoning thus occurs as way to reduce this dissonance through a number of ways, such as changing one’s own beliefs, attempting to change the source’s opinions, finding evidence that supports their own views, or outright rejecting the evidence.[12]

Cognitive dissonance and biases

[edit | edit source]Many cognitive biases affect our thinking, especially reasoning, and are linked intrinsically to our motivations, beliefs and attitudes. Several biases exist and can be characterised into different types based on how they affect cognition, such as biases specific to groups, decision-making, and motivation. A common bias of these groups is confirmation bias and is related, like motivated reasoning, to the concept of cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance

[edit | edit source]Cognitive dissonance occurs when an individual experiences two cognitive elements that are inconsistent with each other. This inconsistency causes discomfort or a feeling of negative arousal[12] and therefore individuals are motivated to reduce or remove the inconsistency. This is done by altering one of the cognitive elements that is causing this dissonance. For example, as provided by Kunda (1990)[2], the cognitions “I believe in X” and “I have stated or done not X” are dissonant and therefore, to reduce this, people will change their beliefs to bring them into correspondence with their actions.

|

Leon Festinger and the end of the world Cognitive dissonance was first described by Leon Festinger in 1957 after his study of a UFO cult whom were convinced the world would end in 1954. When the day came and went, Festinger recounts how cult members began experiencing cognitive dissonance - the world had not ended and they were looking for reasons that would ease the discomfort they felt from the inconsistencies facing them. Eventually, the cult lead explained to her members that she received a message that told her God had decided to spare them and, thus, they were able to reject the evidence that the end of the world wasn't real and go back to spreading their doomsday ideology. Want to read more about the UFO cult? Check out Doomsday prepping motivation: What motivates doomsday prepping? |

Confirmation bias

[edit | edit source]Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out or interpret information that confirms a conclusion or reinforces pre-existing beliefs, especially when an individual is motivated to accept the conclusion as valid.[11] This bias acts as a filter through which people embrace the information they see as supporting while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt. In the case study of Leon Festinger and the end of the world, confirmation bias also plays a significant role. The cult were bias to information provided to them and used confirmation bias to interpret and convince themselves of the belief that they had been saved rather than believing the doomsday ideology was a lie (see also belief perseverance effect).

Treacherous trio

[edit | edit source]Does this sound familiar? Confirmation bias and motivated reasoning go hand in hand; where confirmation bias is a deliberate tendency to find or notice supporting information; motivated reasoning is used to accept information that agrees with our beliefs while critically evaluating that which don't. Together, confirmation bias and motivated reasoning work together to reduce or eliminate cognitive dissonance. By employing both cognitive processes, new information is processed in a way that adheres to already prior held beliefs and attitudes that are aligned with our motivations and reduce our cognitive discomfort.

| Read this! Confirmation Bias & Motivated Reasoning Jonathan Maloney's blog post provides great examples of confirmation bias and motivated reasoning at play. |

Effects of motivated reasoning

[edit | edit source]There are both positive and negative effects of motivating reasoning on our lives, as biases are typically seen as a threat to rational and critical thinking, facilitate self-serving behaviours, and can lead individuals to believe in controversies and conspiracies. For examples, Kunda (1990)[2] states that motivated reasoning can be beneficial for mental health, as the illusions of unrealistically positive views of oneself and the world are adaptive. However, these illusions can be made dangerous if more objective reasoning is required and better for adaptive purposes, such as the seriousness of an illness, or committing a crime.

A threat to critical thinking?

[edit | edit source]Critical thinking is the cognitive process by which we make decisions that can be defended with evidence and knowledge determined through deeper evaluative processes.[13] There are several characteristics of critical thinking that stands in contrast with motivated reasoning. Critical thinkers:

- always seek the truth

- are fair in evaluations and others’ views

- sceptical of information

- open-minded and willing to have their believes challenges

- able to formulate judgements with evidence and reason

As both motivated reasoning and confirmation bias affect our critical thinking, the capacity to change our minds or approach issues in a new way, is neglected.

Self-serving behaviours

[edit | edit source]Research suggests that motivated reasoning can alleviate self-condemnation and/or guilt that results from behaviour deemed unethical or with harmful implication for others.[14] This self-serving behaviour can be used through motivated reasoning to rationalise things like sweat-shop labour. Individuals also use motivated reasoning to interpret the contact in way that justifies their actions, or that sees themselves as being entitled to things such as a larger shares of resources from work, or buying a product produce with sweat-shop labour.

Another example of how motivated reasoning can produce self-serving behaviours can be demonstrated in gun ownership and the focus of blame for mass shootings. Research by Joslyn & Haider-Markel (2017)[15] investigated how gun owners might engage in a form of motivated reasoning that concludes guns as being not to blame for mass shootings, like that of Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012. While guns are the target of public scrutiny and policy change, there are a range of motivations that affect self-serving behaviour, such as the need for protection and enhancement of self-esteem, that allow individuals to engage in motivated reasoning. As gun owners have a perceived stake in the topic, they are more inclined to engage in motivated reasoning that dismissed or criticises gun control more heavily than others.

Controversies, conspiracies, and science denialism

[edit | edit source]Motivated reasoning plays a significant role in fuelling controversies, conspiracies and science denialism. Especially in a highly polarised time of misinformation and controversy, evidence-based conclusions are becoming less meaningful and motivated reasoning more common. Considering most conspiracies or controversies revolve around topics on politics, science, and religion that most individual’s hold strong beliefs or attitudes on, it’s no surprise that willingness to be open-minded or challenged on an issue is non-existent. However, some issues, like climate change, aren’t facilitating motivated reasoning due to a lack of information. Quite the contrary. Research shows that conspiracies have the potential to be socially or politically linked and that an individual’s commitment to particular groups or ideologies, creates a stronger facilitation of motivated reasoning.[16]

| Task time! Check out these conspiracy theories below and think about how motivated reasoning plays a role in each. Examples of conspiracies include:

|

Pathways to rational thinking

[edit | edit source]Watch this!  Why you think you're right -- even if you're wrong | Julia Galef "Perspective is everything, especially when it comes to examining your beliefs. Are you a soldier, prone to defending your viewpoint at all costs — or a scout, spurred by curiosity? Julia Galef examines the motivations behind these two mindsets and how they shape the way we interpret information, interweaved with a compelling history lesson from 19th-century France. When your steadfast opinions are tested, Galef asks: "What do you most yearn for? Do you yearn to defend your own beliefs or do you yearn to see the world as clearly as you possibly can?" |

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Motivated reasoning involves individuals choosing a particular desired conclusion and attempting to construct rational justifications that support it while being highly critically of evidence that doesn’t. As motivated reasoning involves motivation, originating from an individual’s needs, cognitions and emotions, the critical process of finding and assessing information can be easily influenced if one allows it. This is due to the many goals, beliefs, expectations, and attitudes that people may have that all influence motivation.

While motivated reasoning can be beneficial, it also affects people’s lives in numerous ways that may be potentially harmful. These include threats to critical thinking, encouragement of self-serving biases, and the promotion of controversies and conspiracies. By understanding motivated reasoning, perhaps by looking at its components of motivation and reasoning, or its association with confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance, researchers can study further ways to reduce it.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Confirmation bias (Book chapter, 2018)

- Conspiracy (Wikipedia)

- Conspiracy theory (Wikipedia)

- Dissonance (Book chapter, 2011)

- Doomsday prepping motivation (Book chapter, 2019)

- Motivation science (Book chapter, 2020)

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Epley, N., & Gilovich, T. (2016). The mechanics of motivated reasoning. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.133

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

- ↑ Baumeister, R. F. (2015). Toward a general theory of motivation: Problems, challenges, opportunities, and the big picture. Motivation and Emotion, 40(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9521-y

- ↑ Reeve, J. (2016). A grand theory of motivation: Why not? Motivation and Emotion, 40(1), 31–35. https://https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9538-2

- ↑ Evans, J. St.B. T. (1993). The cognitive psychology of reasoning: An introduction. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 46(4), 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749308401027

- ↑ Walton, D. N. (1990). What is reasoning? What is an argument? The Journal of Philosophy, 87(8), 399. https://doi.org/10.2307/2026735

- ↑ Nawara, S. P. (2015). Who s responsible, the incumbent or the former president? Motivated reasoning in responsibility attributions. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 45(1), 110–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12173

- ↑ Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection: An experimental study. Judgement and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/docview/1417401434?accountid=28889

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Baekgaard, M., Christensen, J., Dahlmann, C. M., Mathiasen, A., & Petersen, N. B. G. (2017). The role of evidence in politics: Motivated reasoning and persuasion among politicians. British Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 1117–1140. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123417000084

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Dawson, E., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (2002). Motivated reasoning and performance on the Wason selection task. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(10), 1379–1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702236869

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Carpenter, C. J. (2019). Cognitive dissonance, ego-involvement, and motivated reasoning. Annals of the International Communication Association, 43(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1564881

- ↑ Lack, C. W., & Rousseau, J. (2016). Critical Thinking, Science, and Pseudoscience: Why We Can’t Trust Our Brains (1st ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

- ↑ Noval, L. J., & Hernandez, M. (2017). The unwitting accomplice: How organizations enable motivated reasoning and self-serving behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(3), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3698-9

- ↑ Joslyn, M. R., & Haider-Markel, D. P. (2017). Gun ownership and self-serving attributions for mass shooting tragedies*. Social Science Quarterly, 98(2), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12420

- ↑ Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2015). Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: The moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12234

External links

[edit | edit source]- Confirmation Bias & Motivated Reasoning(Intelligentspeculation.com)

- Motivated reasoning and confirmation bias (Animal-ethics.org)

- Motivated reasoning: Fuel for controversies, conspiracy theories and science denialism alike (Scientific American Blog)

- Motivated reasoning - The skeptics dictionary (Skepdic.com)

- Psychology’s Treacherous Trio: Confirmation Bias, Cognitive Dissonance, and Motivated Reasoning (Why We Reason Blog)

- The Backfire Effect: The Psychology of Why We Have a Hard Time Changing Our Minds (Brainpickings.org)

- Why Do Many Reasonable People Doubt Science? (Nationalgeographic.com)

- Why you think you're right - even if you're wrong | Julia Galef (Youtube)