Motivation and emotion/Book/2019/Doomsday prepping motivation

What motivates doomsday prepping?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Doomsday preppers, also known as survivalists, are groups of people who actively prepare for emergencies which will cause disruptions to social or political order on a widespread level. The need to prepare for the end rose through the twentieth century; this was because of the development of governments, threats of nuclear war, religious groups, the Great Depression, and the development of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction. (Brummett, 1990) The turn of the twenty-first century brought the need to prepare to an all time high. This insurgence began after the September 11, 2001, attack and the several other attacks in London, Bali, and Madrid. This fear of war coupled with an array of environmental disasters, climate change, economic uncertainty, and the apparent vulnerability of humanity spiked interest in doomsday prepping.

Doomsday preppers are currently met with a significant amount of ridicule or fear, mainly due to the rise of the internet. A clear example of this, is National Geographic Channel reality television series Doomsday Preppers which shows the extremes of prepping and how outlandish these people seem with their beliefs. One can also just do a quick internet search and be met with a plethora of blogs and videos, one example is Alex Jones and his website Infowars. Considering the stigma surrounding the doomsday prepper culture it might be assumed that it isn't popular, however, it is only becoming more popular as our world develops. Post-apocalyptic and apocalyptic themes makes up a huge array of popular culture, for example; video games like Fallout, Wasteland; and movies including Oblivion, Mad Max; or even books like The Handmaid's Tale.

The doomsday preppers who are portrayed to the media, are at the extremes of the culture, however, there are people who just want to be prepared for if the unknown happens. These people might just buy extra non-perishables at the shops, or have a contingency plan for if things go south.(The economist, 2014) So while one might not deem themselves an expert doomsday prepper, they still might be someone who prepares themselves. So contrasting the two different ends of the spectrum, we can link internal and external motivators that they both hold. This chapter explores the motivations which causes someone to doomsday prep, as well as psychological theories which helps to explain why people are engaged in this doomsday culture.

|

Focus questions

|

Doomsday beliefs

[edit | edit source]

Doomsday beliefs vary in context some believe in a religious or cultural doomsdays clock, others lean more towards a catastrophic environmental disaster, or it could end by a war brought on by politics and tyrannical rulers. These however, are just overarching topics within each domain the doomsday beliefs vary significantly throughout doomsday prepper groups. A religious doomsday is primarily based around a Cosmic War between Gods or beings of a higher power. In almost all religions, there are scriptures or beliefs of divine battles between Good and Evil and the struggle between creating ultimate order and conquering disorder. (Gregg, 2014) For example there is the belief of the second coming of Jesus Christ, when he will take the believers to Heaven and the nonbelievers will suffer through the Rapture. These religious doomsday prepper believe that current-day events are signs that the end is here, so they prepare for Good to triumph and act accordingly to be taken into eternal salvation. Another religious based doomsday that was theorized was the Mayans believing that at the end of the bʼakʼtun the world would end on December twenty-first, 2012. This was popularized through media and television, as there was a movie depicting the event known as 2012.

In contrast, other Doomsday Preppers believe in a technological downfall, bringing civilizations to their knees. A technological apocalypse affects people in a domino effect, we wouldn't be able to use anything which needed power, so therefore we would be brought back to the pre-industrial revolution (Tynan, 2010). An example of this is a terrorist attack targeted at Wall Street, using an e-bomb there would be equipment failures and power outages on a huge scale. Not only would this shut everything down, but it would cause the financial market to shut down. With the market being offline, it would reverberate and cause massive changes to the market worldwide. It would not only effect America economically, but it would filter sheer panic to everyone else and would cause many other social issues. Therefore, these types of preppers tend to have shelters built, food stockpiled, and have their own power source; this way they can sustain themselves in any type of event.

Personality

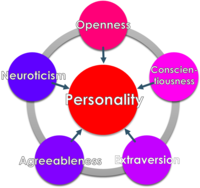

[edit | edit source]Personality is defined as "a dynamic organisation, inside the person, of psychophysical systems that create the persons' characteristics, pattern of behaviour, thoughts and feelings." (Allport, 1961) While everyone is unique in their own right, people who share similar beliefs or lifestyles are likely to hold the same personality traits. Therefore, those who are motivated to doomsday prep would have significantly similar personality traits. Using the Five Factor model as our starting point, we can see that specific personality traits can motivate doomsday beliefs. These personality traits positively correlated with conspiracy mentality, and Social Dominance Orientation. (Fetterman, Bastiaan, Landkammer, Wilkowski; 2019)

Five-factor model

[edit | edit source]The Five Factor Model, otherwise known as the Big 5, uses trait perspective to describe a persons personality. The Five Factor Model consists of five over-arching personality traits which are openness to experience, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism and conscientiousness (McCrae, Costa;2005) Each trait consists of six facets, every individual is then scored on each trait dimension, an example of this is extraversion at one end and introversion at the other. (Major, Tuner, Fletcher; 2006) Each person scores slightly different on each dimension, which is what makes us unique. However, when comparing doomsday preppers results using the Five Factor Model, it is evident that they hold very similar personality traits. (Fetterman, et al; 2019)

Openness to experience is measured through six different domains, these are; fantasy, aesthetics, actions, ideas and values, as well as liberalism. (Costa, McCrae; 2005) Doomsday preppers have been found to score low on openness, the traits they hold are conservative values, judge in conventional terms, uncomfortable with complexities, and moralistic (Fetterman, et al., 2019)

Extraversion is made up of three interpersonal and temperamental domains. The interpersonal traits are warmth, gregariousness, and assertive; while the temperamental traits are; activity, excitement seeking, and positive emotions. (Costa, McCrae; 2005) Doomsday preppers were then found to score low on extraversion and were found to be emotionally bland, avoiding close relationships, over control of impulses, and submissive. (Fetterman, et al. 2019)

Agreeableness is made up of six domains; straightforwardness, compliance, altruism, modesty, tender-mindedness, and friendly compliance. (Costa, McCrae; 2005) Doomsday preppers were found to have low agreeableness, this is referred to as antagonism; and are seen as critical, sceptical, push limits, and expresses hostility. (Fetterman, Et al., 2019)

Neuroticism is scaled on six domains; impulsiveness, vulnerability, anxiety, angry hostility, depression, and self-consciousness. (Costa, McCrae; 2005) Doomsday preppers were scored high on these domains, they were more thinned skinned, prone to anxiety, irritable, guilt-prone. (Fetterman, et al., 2019)

The final facet making up the Five-Factor Model is conscientiousness which includes; competence, dutifulness, self-discipline, deliberation, and achievement striving. (Costa, McCrae; 2005) Doomsday preppers were found to score lower on these domains, they engage in fantasy, self-indulgent, gratification, inability to delay, and the eroticism of situations. (Fetterman, et al., 2019)

Conspiracy mentality

[edit | edit source]|

Quotes from Armeggedon believer

"We are not righteous people, only they will go to heaven, the others will stay here on earth to go through terrible sufferings, I don't want to die like the others. That's why I'll die now." |

Conspiracy mentality was first coined by Moscovici (1987) who defined it as the tendency in which a person subscribes to theories blaming a conspiracy of malevolence on a group for important societal phenomena. Usually these theories contradict a common explanation and that their explanation of the event is caused by powerful individuals. (Swami, Chamorro-Premuzic, Furnham; 2010) The consequences of this mentality, can cause people to engage in political action to undermine the perceived conspirator, or to disengage if the conspiracy is too overpowering. While they can cause political action, conspiracy beliefs are powerful in manipulating our lifestyles, and health behaviours as well. (Bruder, Haffke, Neave, Kouripanah, Imhoff; 2013) An example of this, was when Harold Camping an American Christian radio host predicted the date of Judgement Day. He predicted that the world would end May 2011, leading up to this event many of his believers sold their possessions and homes to the poor. This also caused more extreme actions, like suicides, one girl was 14 years old and chose to commit suicide rather than suffering through the rapture. In her diaries she expressed concern for the end frequently, which unfortunately led to her death (Dein, 2018).

Social dominance theory

[edit | edit source]One theory that can be used to help explain how certain personality traits can motivate an individual to doomsday prep, would be the Social-Dominance Theory (SDT). SDT was first developed by Jim Sidanius and Felicia Pratto in 1999, and is used to explain the extent to which people accept or reject societal ideologies that legitimise hierarchies or dominance. (Vaughan & Hogg, 2018) These hierarchies are formed through; age, as adults have more power than children; sex, men are seen as stronger; and arbitrary-set, which is based on group hierarchies in different cultural settings.

Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) is a measurable component regarding the attitudes of an individual. This scale is influenced by our group status, socialisation and temperament, and will predict an individuals social and political attitudes (Cohrs, J., Moschner, B., Maes, J., & Keilmann, S. 2005). There are two ends of the spectrum:

- Hierarchy-Enhancing Legitmising Myths: are individuals who are high in SDO, and are supportive of ideologies and groups which behave and sustain dominance. E.g., racism, sexism, stereotypes, and classism. (Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. 2006)

- Hierarchy-Attenuating Legitimising Myths: This means that they score low on SDO and believe in enhancing group based social hierarchy to be more inclusive and egalitarian. E.g., feminism, human rights, communism and socialism. (Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. 2006)

Doomsday preppers have been known to scale high on SDO as they are understood to be competitive and supportive of the idea that it is a dog-eat-dog world. (Fetterman, et al. 2019) SDO is important in identifying and predicting whether individuals are egalitarian or anti-egalitarian, and is used to help interpret the intergroup behaviours related to SDT. The three primary intergroup behaviours which support the theory, institutional discrimination, aggregated individual discrimination, and behavioural asymmetry. (Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. 2006)

Institutional discrimination occurs when an organisations set rules, control the power balance of a group. These organisations are able to influence which individuals are able to receive social value as well as, manipulate and control systematic terror. Institutions which have this control would be government agencies and their effect on media, police and many other organisations. Therefore, democratic institutions are imperative as they would have no arbitrary hierarchies and would promote equality and freedom. (Fischer, R., Hanke, K. & Sibley, C., 2012) In-contrast doomsday preppers scale high on institutional discrimination which means that they are more likely to express prejudice towards disadvantaged groups and support ideologies that maintain social inequality. In the realm of an apocalyptic disaster, this would mean that preppers would view themselves as superior to others and therefore control resource distribution, as they would have the commodities to survive. (Fetterman, et al., 2019)

Aggregated individual discrimination is based on everyday discrimination between individuals. This discrimination can be based on an individuals ethnicity, nationality, social class, sexual orientation, or gender. (Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. 2006) In an apocalyptic scenario, a prepper may refuse to help someone due to their ethnicity or a stereotype that they have been exposed to.

Behavioural asymmetry is displayed in two forms, the first being ingroup bias and the second being self-debilitation. Ingroup bias means to promote acts or beliefs that will promote their own belief. Those who are dominant in a group will display favouritism to acts of another dominant individual, and will favour those who are subordinate. (Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. 2006) An example of this in an apocalyptic approach, would be a male prepper valuing the opinion and beliefs of another male prepper over those who may be younger or of a different gender.

Self-debilitation is understood as subordinates engaging in self-destructive and ingroup-damaging behaviours. this means that subordinate individuals will be more likely to perform in criminal activities, drugs, or violence. (Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. 2006) An example of this in an apocalyptic scenario would be subordinate members acting out and being violent towards other members of the group. While those who are dominate would be calm and act in a way that promoted their group survival.

|

Quiz Time!

Choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

|

Psychopathology

[edit | edit source]Mental health is extremely important in how we conduct ourselves in the world, as it effects the way we think, feel, behave and relate to others. Furthermore, when our mental health suffers it can disrupt our relationships, physical health, and our entire lifestyle causing irreparable damages (Hirschfeld, et al., 2006). Understanding the aetiology, as well as the psychopathology of mental illness will allow us to understand the development of doomsday ideations . This is because these ideologies can develop out of trauma, delusions, or mental illnesses like anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder. Understanding the development and effect these disorders have, can help to comprehend how it motivates the need to prepare for a doomsday scenario.

Trauma

[edit | edit source]Psychological trauma occurs when an individual experiences an extreme stressor that negatively affects their beliefs, values and meaning that is essential to their sense of self. Trauma can cause distress and be extremely painful which can overwhelm the individuals capacity to cope and leave them with feelings of helplessness. An example of a traumatic event would be if an individual lived through a disaster, like a hurricane, war, or rape. Unfortunately, trauma if left untreated can develop in to a myriad of issues, including; PTSD, anxiety, depression, and sleep issues (Ruglass, Kendall-Tackett; 2014). PTSD is an extremely prevalent and disabling disorder as it has high rates of co-morbidity and and suicidal ideology, and it is one of the main psychological risk factors after a natural disaster (Arnbery, Johannesson, Michel; 2013). Therefore, some prepper beliefs are not grounded in a controlled, analytic mental process, rather they can develop out of an adverse emotional experience. (Parks; 2010) The reason for this is because the adverse event heightens our sense-making motivations which makes us sensitive to threats. When we are sensitive to threats and placed in a context which is anxiety-provoking, we become more sensitive to creating doomsday or conspiracy theories to help rationalise and gain a sense of control over a situation. (Van Prooijen, Douglas; 2018) For example, if someone had to live through a catastrophic earthquake where it caused floods and many people died, the trauma and stress could make them believe this is how the world will end. The event could leave the individual feeling helpless and out of control, so to make sense of it they might explain it as an act of God.

Delusions

[edit | edit source]Doomsday preppers have been referred to as delusional, as their ideology is seen as extreme and seperate to mainstream thoughts. For some preppers their intense certainty could be grounded in delusions. A study conducted by Brunet, Birchwadwood, Upthegrove, Michail, & Ross found that 1/3 of people who experienced PTSD after a severe natural disaster also experienced their first episode of psychosis (2012). One of the key features of psychosis is delusions, Oyebode defines this as a perverted view on reality, held with immense conviction, not amenable to logic and with their absurdity or erroneous content easily attributed to others. (2014) The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V) has specified six types of delusions. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

- Persecutory delusion: the belief that they will be harmed or harassed by an individual, group or organisation.

- Referential delusions: belief certain gestures, comments, environmental cues are directed at them.

- Grandiose delusions: belief that the individual has exceptional abilities, wealth or fame.

- Erotmantic delusions: the belief that a specific person is in love with them.

- Nihilistic delusions: belief that a major catastrophe will occur.

- Somantic delusions: a focus on preoccupations regarding health and organ function

Delusions are a core feature of schizophrenia as 70% of individual experience it, it also occurs in 65% of individuals with bipolar disorder when experiencing mania and 20% when having a depressive episode. Delusions can also be attributed to drugs or alcohol, head injuries, epilepsy, Alzheimer's, brain tumors, and many other illnesses related to the brain. (Upthegrove, S.A., 2018) Therefore, it can be understood, that if someone were to experience a horrendous event, like floods, if left untreated they could develop PTSD and experience a nihilistic delusions. Doomsday preppers would be likely to experience either nihilistic or persecutory delusions due to the conviction of their beliefs.

Anxiety

[edit | edit source]The need to prepare for a doomsday situation can also be attributed to the anxiety of the fragility of civilisation. This fragility has been proven through multiple catastrophic events, like; Hiroshima, the March 2011 earthquake and tsunamis that followed, and countless other disasters. (Fernando,G. Miller, K. & Berger, D., 2010) The DSMV defines anxiety as persistent and excessive worry or fear about various domains, like work or school performance, that the individual finds difficult to control or perceive worse than it is. (APA, 2013) Michael Mills establishes this perceived doomsday anxiety through an article with testimonials of real preppers. He establishes that these perceptions of an apocalyptic 'threat' is highly influenced by numerous disaster that have been widely reported and recognised by American culture. The preppers who contributed, stated that they are just preparing for the unknown, and that it would only be for a period of time until authorities would be back in control.

| “ | One needs look no further than turning on the television and seeing the first three big stories that come to mind. […] I mean ISIS, [the Russian invasion of] Ukraine, Ebola. These are all things that likely won’t come home, but I do think that it’s not unrealistic to consider them and at least have it in the back of one’s mind, ‘Ok, what if?’ And not to obsess about it, but at least to just say, ‘Ok, what if there was a catastrophe? - Gloria (Doomsday Prepper) |

” |

Psychological theory

[edit | edit source]

Confirmation bias

[edit | edit source]Confirmation bias is a type of cognitive bias and a systematic error of inductive reasoning and effects how we search for, interpret, as well as memorise information. This bias is displayed when an individual will interpret, favour, and recall information that confirms their own beliefs and will ignore evidence that is contrary to their hypothesis. (Nickerson, R. 1998)

- Search for information: An individual will search for information or evidence by phrasing questions which affirm their theory, this is called a positive test. i.e., If someone is using yes/no questions to find the number and they suspect its 4, they'll ask "is it an even number?" (Nickerson, R. 1998)

- Interpret information: An individual will interpret information that will reaffirm their beliefs and ignore evidence that contradicts it. An individual will also interpret ambiguous information and use it to support their existing position. (Lord, C., Ross, L. & Lepper, M. 1979)

- Memorise information: The individual will also remember evidence that will reinforce their beliefs. This is known as "selective recall", they are more likely to recall certain information because of it. (Hasstie, R. & Park, B., 1986)

An example of confirmation bias in todays society, would be when someone sees a psychic. This is because they will make ambiguous statements and the client will take the information and match it to their own idea. Confirmation Bias is also important in explaining the belief perseverance effect.

Belief Perseverance Effect

[edit | edit source]Belief Perseverance can be understood as the cognitive tendency of an individual clinging to an existing, strongly-held belief even after this belief has been discredited. The individual will ignore, deny, misperceive, or debate contradicting evidence. (Posner, G., Strike, K., Hewson, P. & Gertzog, W., 1982) Festinger spent time with a cult that was convinced that the world would end on 21st of December in 1954, when the prediction failed the believers still clung to the faith. They were bias to information provided to them, and convinced themselves that they were being saved rather than believing that Keech was wrong. (Festinger, L., Riecken, H., Schachter, S. 1964)

|

Case study

In 1956 a UFO religion was formed, and they were known as the Seekers. It was a small group of people in Chicago and was formed by Dorothy Martin (alias Marian Keech), who believed that aliens from the planet Clarion had contacted her to warn of a world-ending flood before dawn on December 21, 1954. All of the members refused to do press interviews or any publicity. People weren't let into Keech's home unless they proved they were believers. Keech receives a message at 4:45 am and it said that God of Earth has saved them from destruction, all thanks to his follows staying up all night. The next afternoon papers are called and the follows are preaching this message. This shows belief perseverance at work and how Leon Festinger developed this theory (Festinger, L., Riecken, H., Schachter, S. 1964) |

|

Quiz Time!

Choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

|

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Overall, it is clear that Doomsday prepping can be motivated by various factors with an individual. The different motivators which can motivate an individual include, their personality and traits, their openness to conspiracies, and their social dominance orientation can cause them to prep. SDT helps to explain how the combination of personality traits and intergroup behaviours can be understood to explain why some individuals are more likely to doomsday prep than others. It is also established that ones mental health can be a factor in their need to prepare, trauma plays a huge role in this. Due to its progressiveness, if left untreated it will develop into other illnesses like PTSD, depression, or anxiety. It can also be understood that those who suffer from delusions, can also be more inclined to doomsday prep, as they must prepare for their own extreme catastrophes. Confirmation bias and belief perseverance can be used to understand how these ideologies are held with such conviction, even after it has been disproven or is not believed by mainstream society.

While this chapter has provided some insight into the reason some individuals may be motivated to be a doomsday prepper, there needs to be more research and studies conducted to explore the topic further. This is because many of the studies that are related to this field look at the extremes of it, they are mainly critical and discuss these individuals as if they were off the National Geographic's Doomsday Preppers, while many people may just be on the lower end of the spectrum.

| This chapter is an overview of some motivations for these acts. It does not cover every possible motive or reason. Instead, it serves as an informational tool for readers and highlights the importance of the topic.

|

See also

[edit | edit source]- Personality and motivation (book chapter, 2010)

- Confirmation bias motivation (Book chapter, 2018)

- Stress and emotional health (Book chapter, 2011)

- 2012 (Movie depicting the Mayan end of the world) (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]American Psychiatric Association (2013). Depressive Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing

Arnberg, F., Bergh Johannesson, K., & Michel, P. (2013). Prevalence and duration of PTSD in survivors 6 years after a natural disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 347-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.011

Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N., & Imhoff, R. (2013). Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225

Brummett, B. (1990). Popular economic apocalyptic: The case of Ravi Batra. Journal of Popular Culture, 24, 153-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1990.2402_153.x

Brunet, K., Birchwood, M., Upthegrove, R., Michail, M., & Ross, K. (2012). A prospective study of PTSD following recovery from first-episode psychosis: The threat from persecutors, voices, and patienthood. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, pp 418-433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.2012.02037.x

Cohrs, J., Maes, J., Moschner, B., & Kielmann, S. (2007). Determinants of human rights attitudes and behavior: A comparison and integration of psychological perspectives.Political Psychology, 28, 441-469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00581.x

Cohrs, J., Moschner, B., Maes, J., & Kielman, S. (2005). The motivational bases of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation: Relations to values and attitudes in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1425-1434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205275614

Costa. R., & McCrae, P. (2005) Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. (2nd ed) New York: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

Dein, S. (2018). Prophecies are dangerous things: Mental health implications of prophetic disconfirmation. Journal of Religion and Theology, 2, 1-5. Retrieved from https://www.sryahwapublications.com/journal-of-religion-and-theology/pdf/v2-i3/1.pdf

Fernando, G., Miller, K., & Berger, D. (2010). Growing pains: The impact of disaster-related and daily stressors on the psychological and psychosocial functioning of youth in Sri Lanka. Child Development, 81, 1192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01462.x

Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1964). When Prophecy Fails. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Fetterman, A., Rutjens, B., LandKammer, F., & Wilkowski, B. (2019). On post-apocalyptic and Doomsday prepping belief: A new measure, its correlates, and the motivation to prep. European Journal of Personality, 33, 506-525. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2216

Fischer, R., Hanke, K., & Sibley, C. (2012). Cultural and institutional determinants of social dominance orientation: A cross‐cultural meta‐analysis of 27 societies. Political Psychology, 33, 437-467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00884.x

Gregg, S. (2014). Three theories of religious activism and violence: Social movements, fundamentalists, and apocalyptic warriors. Terrorism and Political Violence, 28, 338-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.918879

Hastie, R., & Park, B. (1986). The relationship between memory and judgment depends on whether the judgment task is memory-based or on-line. Psychological Review, 93, 258-268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.3.258

Hirschfeld, R. M., Montgomery, S. A., Keller, M. B., Kasper, S., Schatzberg, A. F., Moller, H. J., Healy, D., Baldwin, D., Humble, M., Versiani, M., Montenegro, R., & Bourgeois, M. (2000). Social functioning in depression: A review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61, 268-75. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v61n0405

I will survive; Preparing for the apocalypse (2014) The Economist; London. Retrieved from; https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/docview/1640720552/citation/142E99B999F5456FPQ/1?accountid=28889

Lord, C., Ross, L. & Lepper, M. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Psychological Association, 37, 2098-2109. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098

Major, D. A., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, T. D. (2006). Linking proactive personality and the Big Five to motivation to learn and development activity.Journal of Applied Psychology, 91 927-935. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.927

Mills, M. (2019) Preparing for the unknown... unknowns: 'Doomsday' prepping and disaster risk anxiety in the United States. Journal of Risk Research, 22, 1267-1279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1466825

Moscovici, S. (1987). The conspiracy mentality, in Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy, eds C. F. Graumann and S. Moscovici (New York, NY: Springer), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4618-3_9

Nickerson, R. (1998) Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2, 175-220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Oyebode, F. (2014). Sims’ Symptoms in the Mind: Textbook of descriptive psychopathology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Parks, C. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 257-301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

Posner, G., Strike, K., Hewson, P., & Gertzog, W. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66, 211-227. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730660207

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. "European Review of Social Psychology, 17," 271-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280601055772

Ruglass, L., & Kendall-Tackett, K. (2014). What is Psychological Trauma? In Psychology of Trauma 101 (pp 1-24) New York, United States: Springer Publishing Company

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Unanswered questions: A preliminary investigation of personality and individual difference predictors of 9/11 conspiracisy beliefs. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 749-761. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1583

Tynan, D. (2010, March 15th) Tech apocalypse: Five doomsday scenarios for IT. Retrieved from Infoworlds website: https://www.infoworld.com/article/2628175/tech-apocalypse--five-doomsday-scenarios-for-it.html

Upthegrove, R., (2018). Delusional Beliefs in the Clinical Context. In: Bortolotti L. (eds) Delusions in Context. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Van Prooijen, J. & Vugt, M. (2018) Conspiracy theories: Evolved functions and psychological mechanisms. Perspectives of Psychological Science, 13(6). pp. 770 - 788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618774270

Vaughan, G. & Hogg, M. (2018) Social Psychology. (8th Ed)Melbourne, Vic: Pearson Australia.

External Links

[edit | edit source]- Doomsday Preppers (television series on National Geographic)

- The Survivalist Prepper Podcast

- Ten items a prepper must have (Youtube video)