Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Motivational science

What is the meaning of motivational science and why is it important to take a scientific approach to understanding motivation?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Motivational science is the study of needs, cognitions, and emotions. It articulates how motives express themselves through behaviour, engagement, psychophysiology, brain activations, self-report, and explains why the study of motivation is so important to people’s lives (it contributes positively to important life outcomes) Reeve, 2018.

This chapter breaks down this definition to understand how and when motivation occurs in our lives. Motivational science uses the scientific approach in order to test a hypothesis and provide a logical, systematic answer based on the evidence presented. This in turn, creates theories which give us the best explanation of why motivation exists. This chapter also looks at when we use motivation in our lives and how it influences our choices to participate or not in various situations.

Focus questions:

|

The main question is how do I get motivated?

[edit | edit source]The first thing most people do to become motivated is to become inspired by a stimulus. Watch this video and see how it makes you feel. If You Need Motivation, WATCH THIS! (very motivational)

Feel motivated yet? Unfortunately motivation is a much deeper concept than watching a few videos. The science behind motivation has been developed to help people understand what motivation is and how we become motivated in order to go and achieve our goals. By the end of this chapter, you will understand motivation and know how to apply it in order to achieve your goals.

What is the scientific approach and why is it so important?

[edit | edit source]The scientific approach is a method that requires knowledge to be tested by a hypothesis to determine a logical, systematic answer based on the evidence provided. This is important for the study of psychology as a whole and especially in motivational science as they are not exact sciences, meaning they need enough evidence to support a hypothesis in order to create a theory (best explanation of a concept).

Wieman (2007) found that the scientific approach to learning is effective because it gives the best understanding of what it means to “learn” science. As the study of motivation is not a simple formula, the scientific approach to motivational science is always adjusting and improving to give the best understanding of motivation. It attempts to minimise the influence of bias or prejudice on the experimenter, to give a clear, reliable and valid answer Harris (2008). It provides an objective, standardised approach to conducting experiments and, in doing so, improves their results.

How does the scientific approach work?

[edit | edit source]In order for the scientific approach to work a hypothesis is required, this is the question that will be tested through data that has being collected and if enough valid and reliable information is found a theory can be made and begin to deepen the understanding of that topic. There are two types:

- Null hypothesis: There is no significant difference between specified populations, any observed difference being due to sampling or experimental error.

- Alternative hypothesis: There is a significant relationship between specified populations between two selected variables in a study.

Once establishing your hypotheses you need to create a study in order to test them. This is initiated by gathering participants and performing a relevant experiment within the most accurate environment possible, in order to see what happens. This data is related to the topic being studied, which it can be compared to the general population.

Key takeaways from hypothesis testing: Majaski (2020)

- Hypothesis testing is used to assess the plausibility of a hypothesis by using sample data.

- The test provides evidence concerning the plausibility of the hypothesis, given the data.

- Statistical analysts test a hypothesis by measuring and examining a random sample of the population being analysed.

There are some significant warning signs that stop data from telling us there is/is not a relationships these include:

- Type 1 error: is the rejection of a true null hypothesis (also known as a "false positive" finding or conclusion)

- Type 2 error: is the non-rejection of a false null hypothesis (also known as a "false negative" finding or conclusion)

Power: The probability of making a correct decision (to reject the null hypothesis) when the null hypothesis is false. Probability that a test of significance will pick up on an effect that is present.

Motivational science is not an exact science, therefore in order to present the best approach to explaining something, clear reliable and valid evidence is needed. This is why the scientific approach is so important, with the more research into motivation we undertake, the deeper our insight and understanding of motivational science.

What is motivational science?

[edit | edit source]Motivational science is the study of needs, cognitions, and emotions, articulates how motives express themselves (behaviour, engagement, psychophysiology, brain activations, self-report), and explains why the study of motivation is so important to people’s lives (it contributes positively to important life outcomes) Reeve, 2018.

So lets break down each component to understand its input to motivation.

Needs:

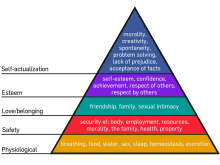

[edit | edit source]A Need is something that is required for a safe, stable and healthy life. There are different types of needs people have, as summarised in Maslow's hierarchy of needs (1943) in Figure 1. As outlined, there are five different types of needs, at the bottom are basic physiological needs like food, water, shelter. Next are safety needs such as employment and security. Next are love/belonging needs such as family and friends. Next are esteem needs such as achievement and respect and finally self-actualisation needs such as having morality. Basically, it is a simplistic method of diagnosing individual needs or wants, and for suggesting methods to motivate individuals based upon these needs in organisations (Guest, 1955).

Cognitions:

[edit | edit source]Cognitions are a set of mental abilities and processes related to knowledge, attention, memory and working memory, judgement and evaluation, reasoning, problem solving, decision making, comprehension and production of language. This aligns with motivation as the cognitive ability to perform a task relies on factors such as self-belief, assessing cost/benefits of time or effort, and the desire for a specific outcome. A study by (Heckhausen, 1977) found that cognitions lead to actions and are an important component in achieving motivation.

Emotions:

[edit | edit source]Emotions are biological states associated with the nervous system which originate from neurophysiological changes associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioural responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. Some basic emotions include happiness, sadness, joy, anger and excitement. The impact of emotions on motivation surrounds feelings associated with participating or not in a situation. For example, if something makes you happy, like going to the beach, your motivation towards going to the beach will be high, compared to something that causes discomfort, e.g. a horror movie, which would lower your motivation to participate based on the feelings associated with pursuing that activity.

Bringing everything together

[edit | edit source]Motivation occurs with every situation or activity a person choses to participant in or not. The amount of motivation a person puts in, is on how the person is feeling (emotions) about a necessity (need) and what actions (cognitions) are required in order to achieve it. Motivation combines personal needs, cognitions and emotions for an outcome that is best suited for us. Each person has different motivation and motivational reasoning for everything, displaying the importance of using the scientific approach, as each individual is different, requiring an analysis of data trends and common factors to understand how motivation affects us as humans .

What do we use motivation for?

[edit | edit source]Motivation applies to all areas of life including work, school, sport, safety, achieving goals and implementing change. Motivation can be high, low or non existent depending on the individual's needs, cognitions and emotions.

Examples:

High motivation: A person wanting to lose weight and get fit

You need and want to lose weight in order to achieve a healthier lifestyle and to fit into clothes better, which motivates you to change your habits. The actions taken to lose weight means exercising 3-4 times per week and being active, whilst eating a healthier diet. The benefits include a healthier lifestyle, and promoting happiness by working towards a goal and achieving results, which reinforces motivation and consistency.

Low motivation: To cook dinner

Eating is a need essential for maintaining hunger and survival, however, you have had a long and tiring day at work including all you want to do is sit on the couch and not move, cooking is the last thing on your mind. Therefore you end up ordering pizza and having it delivered. The motivation was low to cook however their are alternatives and to have dinner in a way you feel comfortable doing.

Motivation theories

[edit | edit source]

Motivation cannot be defined by one theory or definition. In motivational science there are multiple theories that help us understand motivation as a whole. A theory must undergo the scientific approach in order to be accepted and used to help explain motivation. As defined above, motivational science is the study of (needs, cognitions, and emotions), which expresses our (behaviour, engagement, psychophysiology, brain activations, self-report) and then tells us why we participate in things or not.

Figure 2 displays a basic flow chart of how motivational theories are broken down into sub categories of different motivation aspects.

Here are some major motivational science theories that explain motivation in everyday life:

Cognitive dissonance theory

[edit | edit source]Cognitive Dissonance is defined when one's attitudes and beliefs conflict or when our behaviour conflicts with our attitudes. As humans who make assumptions cognitive dissonance can cause problems. When people have different attitudes or behaviour about something it can create conflict.

In his theory of cognitive dissonance, Festinger (1957) proposed that individuals feel psychological discomfort (i.e., negative affect) when they hold two or more cognitions that conflict with one another, such that one cognition implies that the other ought not to be true. Previous research by (Chiou & Wan, 2007) illustrates that this conflict is caused by an external factor which motivates attitude change. This implies that your attitudes or behaviours will never change until you accept and understand other points of view and are able to come to a resolution. This can lead to an improved behavioural change and the ability to compromise and have compassion towards others.

Example: Smoking

Jake is 32 and smokes cigarettes every day, regardless of knowing it can lead to health conditions like lung cancer. He smokes because he thinks it helps with his anxiety and that he doesn't smoke enough to cause serious damage to his body. Jake has reduced the dissonance as he has convinced himself his behaviour is okay, even when others tell him to stop smoking.

Achievement goal theory

[edit | edit source]Achievement goal theory is a psychological theory of intrinsic motivation that considers how beliefs and cognitions orient us towards achievement or success, especially in relation to two styles, task (mastery) and ego (performance) Kremer et al. (2012).

Task goals (mastery): A goal is something you want to achieve , the tasks are the smaller steps in order to reach that goal.

Performance goals (performance): Are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time bound (SMART). These are how we process in order to reach a goal.

A study by (Church, Elliot, & Gable, 2001) investigated the intersection between person and context within achievement goal theory and have thus studied how goal structures relate to achievement goals. The results concluded that task and performance goals work best when they are working together towards the same goal. This is supported by (Dweck & Legget, 1988) where a mastery goal orientation reflects a focus on learning and understanding, whereas a performance goal orientation reflects a focus on demonstrating one’s ability or competence, often in relation to others. Roberts (2001) outlined that mastery or performance climates are related to how significant others (e.g., teacher, coach, or parent) structure the environment, and having a safe and encouraging environment can potentially help with the achievement of goals.

Example: Wanting to get fitter

Wanting to improve fitness is a task goal. In order to get fitter, we need to use our performance goals (SMART) to methodise a way (tasks) to achieve this goal. The specific goal is to get fitter, which could be measured by weight loss over multiple weeks and how far you can run each week (in kms). If you are losing weight consistently and running further each week, then you are progressing. The goal must be achievable, therefore tailoring tasks to your current fitness level is required to prevent injury or burnt out. This could involve running 2-3 times per week and starting with 2km, which can increase to 3-4 times per week or further distances as fitness improves. The goal must be resilient, meaning consistency and commitment is needed to achieve your goal. Finally, the goal should be time bound, meaning you need to achieve your goal within a specific time frame, e.g. losing 5kg over 8 weeks. After a few months of progression and consistent running, you will be able to achieve your task goal of becoming fitter.

Drive theory

[edit | edit source]Drive theory is based on the principle that organisms are born with certain psychological needs and that a negative state of tension is created when these needs are not satisfied. When a need is satisfied, drive is reduced and the organism returns to a state of homeostasis and relaxation. We have two types of drives, primary and secondary:

- Primary drives: Things that our body needs, like food and water

- Secondary drives: Things we need because they are associated with primary drives, like money which can buy food and other things we need

There are many types of drive that give us satisfaction. Different types of drive do not vary dynamically, but all entail a state of tension, where release ‘‘feels good.’’ Indeed, the drive ‘‘types’’ actually constitute a single id tendency Juni (2009). This essentially means that when something feels good we are rewarded through brain activity which gives us feelings of satisfaction like fullness, love, excitement etc. after which the body will demand more of over time. Drive theory states that these drives can motivate people to satiate desires by responding in ways that will most effectively achieve satisfaction.

Example: Getting hungry

Our body attempts to maintain a healthy balance, this is known as homeostasis, therefore, not eating for seven hours while actively using energy in the body leads to hunger, thus increasing the drive to eat. In order to return to a healthy balance you decide to eat dinner (primary drive). Additionally, you have just come from work and have received a pay-check (secondary drive), and decide to go out to dinner to eat. After fuelling your body with food, the hunger need is satisfied and the drive to eat is lowers, returning to a healthy balance.

How do we apply it to life

[edit | edit source]Throughout this chapter, we have learnt what motivation is and how the scientific approach is used to develop the understanding motivational science. It is also important to understand that we use motivation in our everyday lives and with every situation there is some aspect of motivation placed in participating in something or not. Our motivation reflects on what will give us the best outcomes for a situation, our brains process the rewards and punishments of a situation and helps us decide what is best. This essentially comes from classical conditioning, operant learning and observational learning, these theories are about rewards vs punishments. A study by Fareri et al. (2008) called reward-seeking an impetus, a motivating force of everyday human behaviour. This plays a major role in motivational value of rewards (Berridge and Kringelbach 2011). In summary, people have experienced, learnt, won and loss, observed and participated in many things throughout their life and from these experiences they understand what works for them and what leads to the best outcomes when confronted with a similar event in future.

Important note: lacking motivation or choosing to not participate is not necessarily a "bad" thing. If something is too difficult or you are not passionate or do not care about something, then pursuing this goal is likely not worthwhile and may waste time, money and resources to achieve something you do not want.

Practice example: Daily activities

You will be given some situations and it is your choice to pursue in them or not. Make a list of the rewards and punishments for each situation and pick an outcome based on whether it will benefit you to do it or not, your motivation towards each situation will reflect your answer.

| Situations/activities | Rewards | Punishments | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Going to the gym tomorrow morning |

|

|

I will not go to the gym early in the morning because I have not been sleeping well, so I will go tomorrow afternoon after a good amount of sleep. |

| Reading the extra readings for a University class |

|

|

I will read the extra readings, because I did not do well on the last test and want to get better marks on the next one. It will take a bit of time but I think it will help me in the future if I put in the extra work now. |

Give it a go yourself:

- You have been asked to work an extra shift on Saturday night, but your friend invited you to a party, what do you choose?

- Should you have ice-cream for desert?

- Should you get take-out or cook dinner at home?

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

[edit | edit source]Motivation is the thing that helps us achieve our goals. We understand that individuals will pursue goals they want to achieve and avoid ones they don't have interest in. This reiterates an important aspect of pursuing goals: rewards and outcomes.

- Intrinsic motivation: Participating in something, not for a reward, but rather because you enjoy doing it. For example, joining a sports team to play for fun

- Extrinsic motivation: Participating in something to receive rewards from your environment. For example money, grades and fame

Once again, the intrinsic and extrinsic rewards reflect our motivation towards pursuing something. Sometimes, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation can co-exist even though they are the opposites. For instance, you could be studying a master's degree in psychology because you enjoy the topic, but you also want the reward and prestige of achieving a master's degree. In this case there are both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations driving you to study.

For example: Applying for a new job

| Why go for a new job | Type of Motivation | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Need a change | Intrinsic motivation | Your job became repetitive and boring, you have lost interest and passion, therefore making a choice within yourself to find something you are passionate about. |

| Personal challenge | Intrinsic motivation | You feel the job is too easy and want to take on more responsibility, this decision is for you to grow and develop your skills to produce great work. |

| Forced to do so | Extrinsic motivation | You have been fired or made redundant, therefore you need to find a new job. |

| Position is a promotion | Intrinsic motivation | You enjoy your job and have been working long hours and putting in work on weekends with the goal of receiving a promotion, now your company is offering an exciting new role in a higher position. |

| Higher salary | Extrinsic motivation | Money may be a factor in deciding on a new job, therefore you go to a larger company which offers more money. |

| Relieve stress | Intrinsic motivation | Your recent job was very stressful and required long hours with little leave, the job has affected your mental health, therefore a new job that is more suited to your lifestyle and has flexible hours may relieve the previous stress. |

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Motivation is more complex than simply watching a video. It originates from an individual's needs, cognitions and emotions and programs the brain to strive to achieve an outcome. Motivational science has been developed through the scientific approach which has created a deep understanding of what motivation is, how motivation works and when to use it. As motivational science isn't a simple formula, it is always developing and changing in order to give the best explanation as to "why" do we do things. Now you too can have a great understanding of motivational science which can explain why you pursue certain things or not. This information may help you with conflicts, as you now understand that you must contemplate what will work for you and decide if something is worth your time, money and/or resources.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Motivation and emotion/Book/2019/Motivation measurement (Book chapter, 2019)

- Motivation (Wikiversity)

- Drive reduction theory motivation (Book chapter, 2017)

- The puzzle of motivation (Dan Pink, YouTube)

References

[edit | edit source]- Chiou, W.B., & Wan, C.-S. (2007). Using cognitive dissonance to induce adolescents’ escaping from the claw of online gaming: The roles of personal responsibility and justification of cost. Cyber Psychology & Behaviour, 10, 663-670. http://doi.org/gqz

- Church, M. A., Elliot, A. J., & Gable, S. L. (2001). Perceptions of classroom environment, achievement goals, and achievement outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 43–54. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/0022-0663.93.1.43

- Dweck, C., & Leggett, E. (1988). A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273.

- Fareri, D. S., Martin, L. N., & Delgado, M. R. (2008). Reward-related processing in the human brain: Developmental considerations. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 1191–1211

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Guest, R. H. (1955). Men and machines: An assembly line worker looks at his job. Personnel, 31, 500.

- Heckhausen, H. (1977). Achievement motivation and its constructs: A cognitive model. Motivation and Emotion, 1, 283–329. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00992538

- Juni, S. (2009). Conceptualisation of hostile psychopathy and sadism: Drive theory and object relations perspectives. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 18(1), 11–22. https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1080/08037060701875977

- Kremer, J., Moran, A., Walker, G. & Craig, C. (2012). Achievement goal theory. Key concepts in sport psychology (pp. 80-85). doi: 10.4135/9781446288702.n15

- Reeve, J. (2018). ''Understanding motivation and emotion'' (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Roberts, G.C. (2001). Understanding the dynamics of motivation in physical activity: The influence of achievement goals on motivational processes. In G.C.

- Wieman, C. (2007). Why not try, a scientific approach to science education? Change, 39(5), 9–15. doi: https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.3200/CHNG.39.5.9-15

External links

[edit | edit source]- Classical conditioning (Wikipedia)

- Cognitions (Wikipedia)

- Cognitive Dissonance (j_solis07, YouTube)

- Drive theory (Drive theory, Iresearchnet)

- Drive theory (Wikipedia)

- Emotions: (Wikipedia)

- Hypothesis (Wikipedia)

- If You Need Motivation, WATCH THIS! (very motivational) (Be inspired, YouTube)

- Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation can co-exist (Parenting for brain)

- Key takeaways from hypothesis testing: ( Christina Majaski, Investopedia)

- Needs (Wikipedia)

- Observational learning (Wikipedia)

- Operant learning (Wikipedia)

- Scientific method (William Harris, Howstuffworks.com)

- The puzzle of motivation (Dan Pink, YouTube)

- 52 examples of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Mindmonia, YouTube)