Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Antidepressants and motivation

What are the effects of popular antidepressants on motivation?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

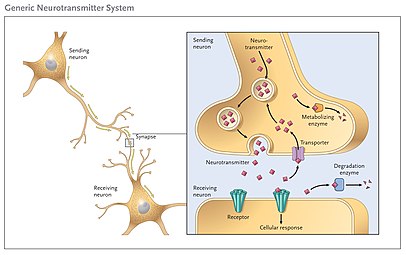

Motivation is the psychological construct that describes the mechanisms by which people, individually and collectively, choose a particular behaviour and persist with it (McInerney, 2019). Motivation can be both intrinsic and extrinsic. Antidepressants work by targeting monoamines, particularly serotonin and noradrenalin in synapses, by blocking their transporters (Rauma et al., 2016). The chemical substances in the brain that carry information between neurons are called neurotransmitters (Hyman, 2005). Figure 1 shows a neurotransmitter receptor. When neurotransmitters don't function properly it can disrupt the homeostasis of a person (Mittal et al., 2016). Motivational theories can explain how different types of motivations are expressed by a person and why they choose to do the things they do. These can be influenced be both internal and external events.

Focus questions:

|

Motivational theories

[edit | edit source]Motivation is a psychological construct that explains the mechanisms by which individuals select specific behaviors. According to psychologists, it encompasses the internal and external factors that stimulate desire and energy in people to be continually interested and committed to a role, task, or subject, or to make an effort to attain a goal (Souders, 2019). This construct of motivation and the idea behind how to develop positive motivation and positive behaviour has spread throughout all areas of human endeavours (McInerney, 2019). (further discussion required)

Learned helplessness theory

[edit | edit source]Learned helplessness is an animal model of depression (more info required) (Sherman & Petty, 2004). In an experiment conducted in 1967 by Overmier and Seligman, it was found that dogs who were exposed to inescapable and unavoidable electric shocks in one situation, failed to later learn to escape an electric shock in a different situation where a possible escape was available. Soon after, in 1967, Seligman and Maier used this experiment to demonstrate that this effect was caused by the uncontrollability of the original electric shocks given (Maier & Seligman, 1976). Maier and Seligman have hypothesised that when an event is uncontrollable the organism learns that the behaviour and outcomes are independent. This learning produces the motivational, emotional, and cognitive effects of uncontrollability and is the basis for learned helplessness theory (Maier & Seligman, 2016).

Sherman, Sacquitne & Petty (1982) conducted research on the learned helplessness model of depression and the responsiveness to several types of antidepressants. Chronic administration of certain types of antidepressants were found to be effective in reversing learned helplessness. Results showed that administration of antidepressants including imipramine, desipramine, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or doxepin were effective, as well as atypical antidepressants (iprindole or mianserin) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (iproniazid or pargyline).

Maslow's hierarchy of needs

[edit | edit source]

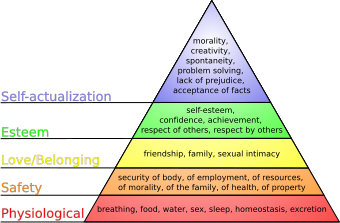

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a motivational psychological theory. It comprises a five-tier, often pyramid shaped, model of human needs. The needs lower on the pyramid, or hierarchy, must be fulfilled and satisfied before a person can attend to the needs higher up the pyramid. As seen in Figure 2, the bottom of the hierarchy upwards satisfies physiological needs first, followed by safety, love/belonging, esteem and finally self-actualisation (Gawel, 1996).

The most basic concept in Maslow's hierarchy of needs is physiological functions, which include breathing, food, water, sex, sleep, excretion and homeostasis. The action of homeostasis is to keep the body regulated. When the body cannot regulate itself properly homeostatic mechanisms trigger appropriate correction responses i.e. returning your body to a regulated temperature (Berridge, 2004). However, sometimes the body requires some help. For example, when the brain cannot regulate dopamine in the mesolimbic system, antidepressants can be useful (see 3.2 dopamine below for more information)

Self-determination theory

[edit | edit source]The central trait of self-determination theory is the distinction between autonomous motivation and controlled motivation. Self-determination theory suggests that autonomous and controlled motivations differ in terms of their basic regulatory processes and the complementary experiences. It also suggests that behaviours can be categorised in terms of the degree in which they are either autonomous or controlled. Both autonomous motivation and controlled motivation are intentional motivations. Together they are contrasted to amotivation, which involves a lack of intention and motivation (Gagne & Deci, 2005).

In an Australian university study conducted at the University of Queensland, the role of autonomy was investigated using both anxious patients (N = 109) and depressed patients (N = 94). Both studies' results showed that a higher need for autonomy was related to improved outcomes and the relationship between them is mediated by improved cognitions (Dwyer et al., 2011).

Test your knowledge

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

|

Test yourself!

|

Neurotransmitters

[edit | edit source]Neurotransmitters are an important type of messenger molecules and control chemical communication between cells. The spatiotemporal propagation of these chemical signals is a crucial part of communication between cells (Polo & Kruss, 2016).

The relationship between depression and a dopamine deficiency in the brain, specifically the mesolimbic pathway has been hypothesised for many years. The monoamine hypothesis, based on the deficiency of one or other monoamines, is commonly suggested to explain the physiopathology of depression. This hypothesis was originally based on noradrenaline and serotonin deficiencies but has now been extended to include dopamine as well (Dailly, Chenu, Renard & Bourin, 2004).

Serotonin

[edit | edit source]

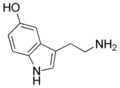

Serotonin is a small molecule, depicted in Figure 3, that functions both as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system and as a hormone in the peripheral tissues of the body (Karsenty, 2013).The synaptic cleft has proved to be a useful model in understanding serotonin action. This is the space between a serotonin-secreting neuron and a serotonin-responding neuron which contains the serotonin receptors. The serotonin-secreting neuron both secretes serotonin and also takes up the secrete serotonin that is in the space between the two neurons. The longer the serotonin is in the synaptic cleft, the great the effect it has on the serotonin-responding neuron (Johnson, 2003). Traditionally, serotonin has been known to influence a range of cognitive, behavioural, and physiological functions which include memory, mood, emotions, sleep, appetite and temperature regulation (Jonnakuty & Gragnoli, 2008).

Dopamine

[edit | edit source]

Dopamine is an organic chemical, shown in Figure 4, that is associated with reward motivated behaviours (Wang, Volkow, Logan, Pappas, Wong & Zhu, 2001). Four main pathways were identified for dopamine transportation in the central nervous system. The first two stem from the ventral tegmental area and follow through to the cortex (mesocortical pathway) and the limbic area (mesolimbic pathway). The third stems from the hypothalamus and projects towards the pituitary gland (tuberoinfundibular pathway) and finally a projection extends from the substantia nigra to the striatum (nigrostriatal pathway) (Dailly et al., 2004). Dopamine has been shown to be associated with reward like behaviour. Lack of dopamine affects activity, sleep, and mood (Riemensperger et al., 2011). In a 2015 article written by Gauthier et al, it is shown that functional imaging studies have indicated that depression is associated with reduced activity in the mesolimbic brain structures that are involved in motivation related behaviours.

Norepinephrine

[edit | edit source]Norepinephrine is a naturally occurring chemical in the body. The structure is shown in Figure 5. It is released into the blood as a stress hormone when the brain recognises that a stressful event may have occurred (Robertson et al., 2013). Norepinephrine, together with adrenaline, increases heart rate and blood pressure. It also helps break down fat and increase blood sugar which provides more energy to the body (Povlock & Amara, n.d.). Low levels of norepinephrine in the body can lead to depression, hypertension, and ADHD (Blows, 2000).

Test your knowledge

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

|

Test yourself!

|

Common types of antidepressants

[edit | edit source]Antidepressants are a psychiatric medication used to treat mood disorders such as anxiety, depression, dysthymia, and many more (Van Leeuwen, 2010). The newer antidepressants tend to have a more select acute biochemical action. This means they inhibit 1 subtype of monoamine oxidase and reuptake a single neurotransmitter. This enables a more direct target of symptoms and helps reduces common side effects associated with taking antidepressants (Rudorfer & Potter, 1989). Antidepressant medication has been shown to improve depressive symptoms in patients presenting with major depressive disorder symptoms which include but are not limited to mood, drive, motivation and concentration (Gauthier et al., 2015).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

[edit | edit source]Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a type of antidepressant mainly used to treat depression but can also be used to treat anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and panic disorder among others (Asnis et al., 2004). SSRIs facilitate serotonergic transmissions by selective inhibition of serotonin reuptake into the presynaptic neurons. The selectivity for clocking the uptake of serotonin is much higher than of norepinephrine or dopamine (Asnis et al., 2004). Common names of the prescribed drug include fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, and citalopram. During long-term SSRI treatment, the most common side effects reported include sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and sleep disturbance (Ferguson, 2001).

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

[edit | edit source]Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a class of antidepressants that inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine (Sansone & Sansone, 2014). Use of SNRIs can include treatment for major depression disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, and osteoarthritis, among others (Sansone et al., 2014). Common prescribed names of SNRIs include duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, levomilnacipran, and venlafaxine. Two most commonly reported side effects of SNRIs are nausea and dry mouth.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

[edit | edit source]Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were among the first antidepressants to be discovered. Two forms of MAOs have been discovered: MAO-A and MAO-B. These two enzymes differ in structure at their substrate-inhibitor recognition sites; however, their active sites remain the same (Youdim, Edmonson & Tipton, 2006). Common MAOIs include isocarboxazid, phenelzine, selegiline, and tranylcypromine. MAOIs have been used to treat depression, as well as panic disorder and social phobia. There is very little documentation on common side effects involved with MAOIs and the frequency at which they occur (Remick, Froese & Keller, 1989). However, early MAOIs have almost disappeared due to something known as the cheese reaction. This is a stimulation of cardiovascular sympathetic nervous system activity caused by a build-up of dietary amines (Youdim et al., 2006).

Tricyclic antidepressants

[edit | edit source]Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are a type of antidepressant that non selectively inhibit the reuptake of not only serotonin but also norepinephrine and dopamine (Ferguson, 2001). Unfortunately, TCAs also block histaminic receptor sites, cholinergic receptor sites and α₁adrenergic receptor sites (Feighner, 1999). Current TCAs include amitriptyline, amoxapine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, maprotiline, nortriptyline, protriptyline, and trimipramine. Common side effects include weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness, and dizziness (Feighner, 1999).

(Far too many links)

Test your knowledge

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

|

Test yourself!

|

Antidepressants and motivation

[edit | edit source]Motivation is a dense and multifaceted concept, and pharmacological research on aspects of motivation is an ever-growing field. Behavioural science fields have described motivated behaviour as being both directional and activational (Salamone, Correa, Yohn, Yang, Somerville, Rotolo & Presby, 2017). The directional aspects of this definition refer to the fact that behaviour is directed either towards or away from a specific situation. For example, approaching food or avoiding a stressful situation (Salamone et al., 2018). There have been several studies, both behavioural and pharmacological, that have provided evidence that depression (a psychiatric disorder) is associated with motivation related deficits (Gauthier et al., 2015).

Decision making that is effort-based is studied using tasks that offer choices. These choices are between high-effort/high reward and low-effort/low reward. These studies have been used to study neural systems, such as the mesolimbic dopamine system and related circuits. These studies address the effort related aspects of motivation (Salamone et al., 2018).

Motivational theories rest on lists, rather than principles, due to a problem of definition. However, the traditional lists include three main variables in relation to motivation: drive, incentive, and reinforcement. There is no agreement as to whether or not these three variables are used to explain only the intensity of behaviour, or if they are used to explain both the intensity and direction of behaviour (Wise, 2004).

Lack of behavioural activation can be seen in many neurological and psychiatric disorders. Terms including fatigue, apathy, psychomotor retardation, amotivation, and negative systems are often used to describe a lack of behavioural activation (Salamone et al, 2018). Major depressive disorder has many psychological aspects that are affected during a major depressive episode, these include mood, drive, motivation, and concentration (Gauthier et al., 2015).

Conditioned place preference is a learned behaviour that is shown in humans, among other vertebrates and it occurs when one place is preferred over another due to being previously paired with rewarding events (Huston et al., 2013). Using conditioned place preference, the positive motivational effect of a range of antidepressants were studied. Results of the study indicated SNRIs produced no place conditioning, whilst the highest dose of the TCA drug, amitriptyline, produced place aversion. The SSRIs produced place preference. Serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine reuptake-inhibiting properties of the antidepressants, along with the serotonin reward pathways, could explain why only the SSRIs were effective in this study (Subhan et al., 2000).

Depressive disorders have a high worldwide prevalence, in 1990 and 2000, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) found that it was a leading cause of burden (Ferrari et al., 2013). Table 1 shows the number of people in the world with depression as surveyed by The Global Burden of Disease and the percentage of diseases this represents.

| Year | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n female | 104.77 million | 114.47 million | 124.36 million | 136.11 million | 144.64 million | 156.70 million | 161.58 million |

| n male | 64.93 million | 71.57 million | 78.64 million | 86.12 million | 91.99 million | 99.67 million | 102.88 million |

| n total | 169.71 million | 186.04 million | 203.00 million | 222.23 million | 236.63 million | 256.37 million | 264.46 million |

| % of population | 3.54% | 3.55% | 3.53% | 3.53% | 3.44% | 3.44% | 3.44% |

(reference for table?) In 2013, a study was conducted using an SSRI known as fluoxetine, in lactating and pregnant rat mothers. The purpose of this study was to determine sexual motivation in male mice when exposed to fluoxetine while nursing or in the womb of their mothers. Results showed that exposure to this drug for pups eliminated preference for a sexual incentive when tested on the sexual incentive motivation test. These results indicate reduced sexual motivation, which is a very common side effect of SSRI use in humans (Gouvea et al., 2008).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Motivation is the psychological construct that describes why people choose particular behaviours. Motivation has many underlying theories, including learned helplessness theory, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and self-determination, but all motivational theories include three main underlying aspects: drive, incentive, and reinforcement.

Neurotransmitters control chemical communication between cells. The monoamine hypothesis is commonly used to explain the physiopathology of depression and involves deficiencies in noradrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine. The three main neurotransmitters involved in emotional regulation are serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine.

When a person’s emotional regulation is not functioning as it should, antidepressants can be an effective tool. These are psychiatric medications used to treat mood disorders such as anxiety, depression, and dysthymia. Common types of antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). MAOIs were among the first to be discovered and most have been discontinued.

Several studies have been conducted to show whether antidepressants affect motivation. In the place preference test conducted by Subhan and colleagues, results showed that SSRIs were the only one with positive results, while SNRIs and TCAs did not show a place preference. In another study conducted by Gouvea and colleagues, results showed rats who were exposed to SSRIs as babies and infants showed a reduced sexual motivation when confronted with the sexual incentive motivation test, which is a common side effect in humans.

Overall, SSRIs show the highest positive effect on motivation, followed by SNRIs and TCAs. There have not been many studies to show whether or not lifelong use, compared to starting later in life, or even other situations, have a differential effect in results on motivation. There have been strong movements to identify particular states of motivation which could help with further studies (Wise, 2004).

Although there are several studies that show antidepressants positively affect motivation there is still the need for more research on this (Gauthier et al., 2015). The Multidimensional Assessment of Thymic States (MATHyS) scale can be a useful tool to determine and measure a person's change in motivation (Gauthier et al., 2015).

Final take home message:

|

See also

[edit | edit source]- Antidepressant (Wikipedia)

- Antidepressants and emotion (Book chapter, 2016)

- Depression and motivation (Book chapter, 2010)

- Depression and motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

- Long-term side effects of antidepressants on motivation and emotion (Book chapter, 2020)

- Major depressive episodes and motivation (Book chapter, 2015)

- Motivation (Wikiversity)

References

[edit | edit source]Berridge, K. (2004). Motivation concepts in behavioral neuroscience. Physiology & Behavior, 81(2), 179-209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.004

Blows, W. (2000). Neurotransmitters of the Brain: Serotonin Noradrenaline (Norepinephrine), and Dopamine. Journal Of Neuroscience Nursing, 32(4), 234-238. https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-200008000-00008

Dailly, E., Chenu, F., Renard, C., & Bourin, M. (2004). Dopamine, depression and antidepressants. Fundamental And Clinical Pharmacology, 18(6), 601-607. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00287.x

Dwyer, L., Hornsey, M., Smith, L., Oei, T., & Dingle, G. (2011). Participant Autonomy in Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy: An Integration of Self-Determination and Cognitive Behavioral Theories. Journal Of Social And Clinical Psychology, 30(1), 24-46. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.1.24

Feighner, J. (1999). Mechanism of Action of Antidepressant Medications. Journal Of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(4), 4-11

Ferrari, A., Charlson, F., Norman, R., Patten, S., Freedman, G., & Murray, C. et al. (2013). Burden of Depressive Disorders by Country, Sex, Age, and Year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Plos Medicine, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1371

Ferguson, J. (2001). SSRI Antidepressant Medications. The Primary Care Companion To The Journal Of Clinical Psychiatry, 03(01), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v03n0105

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal Of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331-362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Gauthier, I., Courtet, P., Vaiva, G., Corruble, E., Llorca, P., Baylé, F., & Gorwood, P. (2015). The ability of early changes in motivation to predict later antidepressant treatment response. Neuropsychiatric Disease And Treatment, 11(1), 2875-2882. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s92795

Gawel, J. (1996). Herzberg's Theory Motivation and Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Practical Assessment, Research, And Evaluation, 5(5), 1-4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7275/31qy-ea53

Gouvêa, T., Morimoto, H., de Faria, M., Moreira, E., & Gerardin, D. (2008). Maternal exposure to the antidepressant fluoxetine impairs sexual motivation in adult male mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry And Behavior, 90(3), 416-419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.025

Huston, J., Silva, M., Topic, B., & Müller, C. (2013). What's conditioned in conditioned place preference?. Trends In Pharmacological Sciences, 34(3), 162-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2013.01.004

Hyman, S. (2005). Neurotransmitters. Current Biology, 15(5), R154-R158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.037

Johnson, L. (2003). Encyclopedia of gastroenterology (1st ed., p. 8). Elsevier.

Jonnakuty, C., & Gragnoli, C. (2008). What do we know about serotonin?. Journal Of Cellular Physiology, 217(2), 301-306. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.21533

Karsenty, G. (2013). Translational endocrinology of bone (1st ed., pp. 1-238). Elsevier/Academic.

Maier, S., & Seligman, M. (1976). Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal Of Experimental Psychology: General, 105(1), 3-46. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3

Maier, S., & Seligman, M. (2016). Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Review. Journal Of Experimental Psychology: General, 105(1), 1. doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

McInerney, D. (2019). Motivation. Educational Psychology, 39(4), 427-429. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2019.1600774

Mittal, R., Debs, L., Patel, A., Nguyen, D., Patel, K., & O'Connor, G. et al. (2016). Neurotransmitters: The Critical Modulators Regulating Gut-Brain Axis. Journal Of Cellular Physiology, 232(9), 2359-2372. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25518

Polo, E., & Kruss, S. (2015). Nanosensors for neurotransmitters. Analytical And Bioanalytical Chemistry, 408(11), 2727-2741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-015-9160-x

Povlock, S., & Amara, S. The Structure and Function of Norepinephrine, Dopamine, and Serotonin Transporters (1st ed., pp. 1-28). Reith Humana Press Inc.

Rauma, P., Honkanen, R., Williams, L., Tuppurainen, M., Kröger, H., & Koivumaa-Honkanen, H. (2016). Effects of antidepressants on postmenopausal bone loss — A 5-year longitudinal study from the OSTPRE cohort. Bone, 89(1), 25-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2016.05.003

Remick, R., Froese, C., & Keller, F. (1989). Common side effects associated with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Progress In Neuro-Psychopharmacology And Biological Psychiatry, 13(3-4), 497-504. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-5846(89)90137-1

Riemensperger, T., Isabel, G., Coulom, H., Neuser, K., Seugnet, L., & Kume, K. et al. (2010). Behavioral consequences of dopamine deficiency in the Drosophila central nervous system. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences, 108(2), 834-839. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010930108

Robertson, S., Plummer, N., de Marchena, J., & Jensen, P. (2013). Developmental origins of central norepinephrine neuron diversity. Nature Neuroscience, 16(8), 1016-1023. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3458

Rudorfer, M., & Potter, W. (1989). Antidepressants. Drugs, 37(5), 713-738. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-198937050-00006

Salamone, J., Correa, M., Ferrigno, S., Yang, J., Rotolo, R., & Presby, R. (2018). The Psychopharmacology of Effort-Related Decision Making: Dopamine, Adenosine, and Insights into the Neurochemistry of Motivation. Pharmacological Reviews, 70(4), 747-762. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.117.015107

Salamone, J. D., Correa, M., Yohn, S. E., Yang, J.-H., Somerville, M., Rotolo, R. A., & Presby, R. E. (2017). Behavioral activation, effort-based choice, and elasticity of demand for motivational stimuli: Basic and translational neuroscience approaches. Motivation Science, 3(3), 208–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000070

Sansone, R., & Sansone, L. (2014). Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors: A Pharmacological Comparison. Innovations In Clinical Neuroscience, 11(4), 37-42. https://doi.org/PMC4008300

Sherman, A., & Petty, F. (2004). Neurochemical basis of the action of antidepressants on learned helplessness. Sciencedirect, 30(2), 119-134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-1047(80)91005-5

Sherman, A., Sacquitne, J., & Petty, F. (1982). Specificity of the learned helplessness model of depression. Pharmacology Biochemistry And Behavior, 16(3), 449-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(82)90451-8

Souders, B. (2019, November 5). Motivation and What Really Drives Human Behavior. PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/motivation-human-behavior/

Subhan, F., Deslandes, P., Pache, D., & Sewell, R. (2000). Do antidepressants affect motivation in conditioned place preference?. European Journal Of Pharmacology, 408(3), 257-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00771-8

Van Leeuwen, J. (2010). Antidepressants (1st ed., pp. 236-246). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Wang, G., Volkow, N., Logan, J., Pappas, N., Wong, C., & Zhu, W. et al. (2001). Brain dopamine and obesity. The Lancet, 357(9253), 354-357. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03643-6

Wise, R. (2004). Drive, Incentive, and Reinforcement: The Antecedents and Consequences of Motivation. American Psychological Association, 50(1), 159-195.

Youdim, M., Edmondson, D., & Tipton, K. (2006). The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(4), 295-309. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1883

External links

[edit | edit source]- Anxiety and depression checklist (K10) (Beyond Blue website)

- How do antidepressants work? (Youtube video, 2013 - 1:25 minutes)

- Pharmacology - antidepressants - SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, MAOIs, Lithium (MADE EASY) (Youtube video, 2016 - 19:23 minutes)

- Taking Antidperessants: The Pros and Cons (Youtube podcast, 2019 - 53:24 minutes)

- Antidepressants and lack of motivation

- Potential side effects of antidepressants