Motivation and emotion/Book/2015/Alcohol and aggression

How does alcohol consumption affect aggression?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Imagine you and a group of friends are going to the pub to see a live band and have a few drinks. You are all enjoying yourselves and having a wonderful time. A few drinks in, some of your friends (Jack, Henry and Lucy) start getting a bit rowdy. The three go to the bar to order more drinks for everyone, but are told that they are cut off for being too drunk, behaving too aggressively and concerning other patrons. Lucy and Jack react by settling down, purchasing some soft drink and muttering about the situation to one another. Henry begins yelling, getting increasingly aggressive by thrashing about and knocking over glasses, until security escorts him outside. Why did Lucy and Jack accept the bartender's orders, while Henry didn’t? Why did Henry get so aggressive after having a few drinks? What is the effect of alcohol on aggression? Are men more aggressive than women, and more likely to become aggressive after consuming alcohol?

Definitions

[edit | edit source]

For the purpose of this book chapter,

Alcohol is ‘any compound in which a hydroxyl group, -OH is attached to a sataurate carbon atom R3COH (McNaught & Wilkinson, 1997).

Aggression is ‘behaviour whose intent is the physical or psychological harm injury or another person’ (Goldstein, 2013).

Alcohol-fuelled aggression is ‘the use of a substance as a mitigating factor in the severity of an offence’ (Young & Kopelman, 2009)

Table 1. Types of aggression and real-life examples

| Active direct aggression | Inactive direct aggression | Active passive aggression | Indirect passive aggression | |

| Physical | Hitting the victim | Playing jokes on the victim | Staging a sit-in | Refusing to do something |

| Verbal | Insulting the victim | Gossiping about the victim | Refusing to speak | Refusing permission |

Alcohol and aggression theories

[edit | edit source]A variety of theories have been utilised to explain the relationship between alcohol and aggression.

Disinhibition theory

[edit | edit source]The disinhibition theory suggests that aggressive behaviour is generally controlled by an individual’s internal forces and willpower (Berkowitz, 1974). The chemical effect of alcohol on the brain increases the likelihood of aggressive behaviour occurring (Gustafon, 1994). Studies by Oei & Baldwin (1994) and Loeber et al. (2009) have shown that alcohol affects an individual’s decision making and choices. However, according to Quigley & Leonard (2006) the chemical affect alcohol has on the brain is only one factor, not the sole cause of aggressive behaviour.

Social learning theory

[edit | edit source]The social learning theory explains alcohol induced aggressive behaviour as a result of social expectation and social situations (Bandura, 1977). Based on this theory, alcohol increases the likelihood of aggressive behaviour because individuals expect it to have this impact. By the reasoning of the social learning theory, alcohol-fuelled aggression is learnt by individuals through their peers, their own behaviour and generalised social situation expectations (Bandura, 1977). As shown in studies by Dermen & George (1989) and Giancola et al. (2010), people are likely to act in an aggressive manner even when they are given a placebo and never consumed alcohol, because this is expected of them.

|

The social learning theory can explain Henry’s behaviour at the bar. The reason he was cut off and began behaving aggressively was because he was drunk and he subconsciously thought his friends and society were expecting him to behave this way. |

General aggression model

[edit | edit source]The general aggression model integrated previous models and theories and suggested there are three stages in aggressive behaviour and its management (Anderson & Bushman, 2002).

- Input - the person and situation, and the biological, environmental, psychological and social factors which affect and influence the behaviour occurring. Personal factors include traits such as sex, attitudes, values and scripts, while situational cues include provocation, aggressive cues, frustration, drugs, incentives and pain and discomforts (Anderson & Bushman, 2002)

- Routes - the input by the personal and situational factors, which then determine and influence the individual’s mental state. The most important internal states include cognitions, arousal and affect (Anderson & Bushman, 2002).

- Outcome - the individual making complex information processes and integrating their own social learning history to undergo an appraisal of the situation (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Although a weak and thoughtless appraisal will lead the individual to behave and act recklessly and involuntarily, a comprehensive appraisal will allow the individual to undertake thoughtful and responsible actions (Anderson & Bushman, 2002).

Frustration-aggression hypothesis

[edit | edit source]The frustration-aggression hypothesis explains that aggression is caused by frustration, when an individual is prevented from reaching a goal/target (Miller, 1941). An individual’s frustration is likely to turn into aggression when a triggering event or moment occurs (Miller, 1941). While frustration can lead to aggression, further research should be undertaken to determine how strong the relationship is between the two (Miller, 1941).

|

In the example of Henry and his friends at the bar, frustration caused Henry to act aggressively. Henry’s goal of attaining more alcohol was prevented by the bartender refusing to sell him more, which made him frustrated and subsequently triggered his aggressive behaviour. |

Table 2. Additional theories and models

| Alcohol and aggression theories and models | Description |

|---|---|

| Attention-allocation hypothesis | Alcohol affects and reduces the amount of attention available to process information, causing decisions to be strongly influenced by inhibitory cues (McMurran, 2013) |

| Alcohol myopia theory | Excess alcohol consumption limits the amount of information that individuals can process (McMurran, 2013) |

| Drive theory | Taking action in order to return to a state of relaxation, after the manifestation of a negative state of tension, which occurs when innate psychological needs are not satisfied (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). |

| Evolutionary theory | Aggression is used as a modified solution to address problems that occur and arise within the environment (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). |

| Excitation transfer theory | Residual stimuli can increase aggressive reactions to an event (Anderson & Bushman, 2002) |

| Indirect cause model | Alcohol compromises important cognitive processes, increasing the possibility of aggressive behavior (McMurran, 2013). |

Understanding the relationship between alcohol and aggression

[edit | edit source]The relationship between alcohol and aggression is complex, yet by examining three specific factors - biological, sexual, cultural - can be better understood. The following sections of this chapter will analyze research findings about the complex relationship between alcohol and aggression. It will also provide suggestions to manage and address alcohol and/or aggression problems, while also taking into account aggression and alcohol theories.

Biological

[edit | edit source]Evidence from twin studies shows that the amount of alcohol an individual consumes is strongly influenced by how much his/her parents drink (Johnson & Leff, 1999). While this report does not focus solely on alcoholism, there is strong genetic evidence that alcoholism runs in families, with individuals being four times more likely to raise children who become alcoholics, if they have also struggled with the disease (Wilson & Nagoshi, 1988).

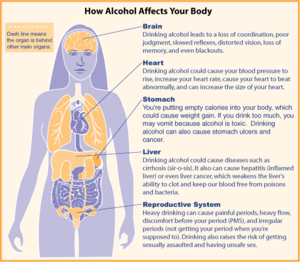

A variety of physiological processes occur when an individual consumes alcohol. Alcohol consumption has a toxic affect on the brain’s central nervous system, which leads to changes in heart functioning, blood supply and metabolism (Eckardt et al., 1998). Alcohol consumption also interferes with the absorption of vitamin B1 (thiamine), which plays a key role in muscle, nerve and heart function (Eckardt et al., 1998).

Multiple studies support the view that aggression is partially genetically determined (Cadoret et al., 1997). Children who are aggressive remain aggressive as adults (Cadoret et al., 1997). In addition, research has shown that a particular gene, the monoamine oxidase (MAOA), located on the X chromosome, produces an enzyme that influences the amount and production of serotonin (a neurotransmitter which reduces aggression and influences appetite, mood and sleep) plays a significant role in the aggression levels of individuals (Buckholtz & Meyer-Lindenberg, 2008). Research by Widom & Brzustowicz (2006) found that children, who had shown lower levels of activity of this gene, were more likely to show aggressive behaviour and tendencies as adults.

Aggressive behaviour is also linked to various regions in the brain, in particular the frontal cortex and the amygdala (Blair, 2004). The amygdala is the area which controls and regulates reactions and perceptions to aggression (Blair, 2004). The prefrontal cortex is the control centre for aggression, helping to control aggressive behaviour and impulses (Blair, 2004).

Gender differences

[edit | edit source]When consuming alcohol, men tolerate alcohol and behave differently than women. Research has shown that males metabolise alcohol better than women (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). Woman generally weigh less than men, so they possess less body tissue to absorb alcohol. With their proportionally higher body ratio of fat to water, women struggle to dilute alcohol within the body to the same extent as men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). A cross cultural study by Wilsnack and colleagues (2002) found that men consistently drank more than women in frequency and quantity, and were more likely to partake in heavy drinking episodes and display adverse drinking consequences.

|

When applying this to Henry and his friends at the bar, if Lucy and the men were the same weight, height and drank the same amount, she would still have a higher concentration of alcohol in her blood than them. |

Women and men experience aggression differently. While both women and men use verbal aggression, men are more likely than women to engage in physical aggression (Bjorkvist, 1994 & Wood & Eagly, 2002)). Research has also shown that women and men react differently to provocation and external aggressive cues (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996). Thus, what may provoke men to act aggressively may be anxiety-provoking for women (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996). A variety of reasons can be used to explain why men are more physically aggressive, and why women rely on indirect or verbal aggression.

- From an evolutionary perspective, men have been engaging in aggressive behaviour forever (Wood & Eagly, 2002). The role of the man was to be a hunter/gatherer, providing for and protecting the family from other males, danger and threats (Wood & Eagly, 2002). Women were more nurturing, and meant to stay at home, cook and care for the young (Wood & Eagly, 2002). As human development progressed, the roles of men and women have remained nearly the same, with some evolutionary psychologists believing that progress has caused gender roles to become more defined (Inglehart & Norris, 2003).

- Cultural norms and society’s expectations dictate that men should be less emotional and more physical than women (Iawamoto et al., 2011). As explained by Iawamoto and colleagues, men who express their emotions are often viewed as weak and emotional, while girls are expected to express emotions (2011).

- Sexual differences dictate differences in aggressive behaviour between men and women. For example, the male hormone testosterone is linked to aggression, and after successful aggression (e.g winning a fight) testosterone causes even more aggression (Carre et al., 2009). On the other hand, women have less testosterone in their bodies, and are more likely to use verbal aggression with other women, rarely relying on physical behaviour (Wilsnack & Wilsnack, 2002). Additional research by Buss & Dedden (1990) has shown that women rely on language in competitive strategies, and men rely on physical behaviour.

|

Based on the previously mentioned gender differences in aggressive behaviour, when Lucy, Jack and Henry were turned away from the bar, Lucy accepted this, said a few bitter words to the bartender (engaging in verbal aggression) and returned to her friends to debrief them. On the contrary, Henry had his anger and frustration provoked which triggered physical aggression, after being turned away from the bar by the bartender and bodyguard |

Cultural

[edit | edit source]Culture plays a significant role in determining how acceptable the amount of alcohol consumed is (Babor, 2010). Australia has a very liberal drinking culture, where excess alcohol consumption is encouraged and supported, and those who don’t drink are considered abnormal (Midford, 2005). Australia’s pride in its drinking culture is causing more damage and harm than ever predicted. Fatalities, harming unborn children, fuelling child neglect and domestic violence are only some consequences that alcohol is having on Australian citizens and society (Midford, 2005). Research by the Australian Education Rehab (AER) Foundation shows that alcohol abuse is costing Australian’s $36 billion annually (Lloyd, 2010). While, various campaigns have been implemented by federal and state governments, the continual impact of excess alcohol consumption in conjunction with aggressive behaviour, is still having devastating consequences.

Consequences of alcohol-fuelled aggression

[edit | edit source]

One-punch assaults are just one of the tragic results of alcohol-fuelled aggression. Recent statistics have shown that one-punch assaults have cost at least 115 lives in the last 15 years (Knowles, 2015). Jennifer Pilgrim analysed the one-punch assault incidents and found that the majority of the people killed were young men after brief aggressive altercations outside night clubs or pubs, where most of the offenders causing the assaults were under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs (Knowles, 2015). Tragically, Pilgrim concluded that most of the deaths could have been prevented (Knowles, 2015).

In 2013, on New Years Eve, 18 year-old Daniel Christie was punched and horrifically injured by Shaun McNeil as a direct result of alcohol fuelled aggression (Margetts, 2015). Christie was punched once in the head, causing him to fracture his skull after falling on the pavement and later died (Margetts, 2015). McNeil had been drinking, and what started off as a tense exchange of words between two random men resulted in the death of one (Margetts, 2015). Less than a year earlier, a similar incident happened in nearly the same spot causing the death of Thomas Kelly (Margetts, 2015). As incidents like these are becoming increasingly common, the concern for the protection of citizen safety is placing pressure on the federal and state governments to act to prevent further deaths and injuries.

How is society managing alcohol-fuelled aggression

[edit | edit source]

With the deaths of both Kelly and Christie, and increased citizens’ concerns for their safety, the NSW government had to act fast. As a result, NSW’s one-punch law was passed in parliament on January 21, 2014 (NSW Government, 2015). The law states that those individuals involved in alcohol-fuelled assaults will face a minimum of 8 years jail for their actions, and spend up to 25 years behind bars if they are supplying or in possession of steroids during the attack (NSW Government, 2015). Action taken by the government and clubs and bars to reduce alcohol-fuelled aggression includes the 1.30am lockout (forcing pubs and clubs to shut their doors and decline new customers after 1.30am), 3am last drink sales, a ban on takeaway alcohol after 10pm, and a freeze on new liquor licenses in the city area (NSW Government, 2015). While, clubs and bars have differing priorities than the government, both agree that the safety and protection of citizens is the highest priority.

According to the first evaluation of NSW’s new policies and laws, alcohol restrictions and lockout laws have reduced assaults by 40% (Olding, 2015). However, the evaluation also revealed that there is no evidence supporting the view that Sydney residents are drinking less alcohol (Olding, 2015). While, the government and alcohol licensed venues are taking action to reduce alcohol-fuelled aggression, addressing and managing alcohol abuse, aggression levels and alcohol-fuelled aggression should also be taken at a personal level.

How can you address and manage alcohol-fuelled aggression

[edit | edit source]The first step to address a problem is to admit that the problem exists. If you are suffering from alcoholism, aggressive behaviour or alcohol-fuelled aggression, there are multiple ways to address your problem and find the right treatment.

First, look at yourself, your personal life and genetic predispositions (Lewis, 2014). Are you male or female (Krug et al., 2002)? Does alcoholism or aggressive behaviour run in your family (Krug et al., 2002)? Are your parents or grandparents suffering from one or all of these issues (Lewis, 2002)? What type of friends do you surround yourself with (Krug et al., 2002)? Are your friends aggressive? Are you irritable and have weak anger control and empathy (Krug et al., 2002)? Answering ‘yes’ to these questions may not conclude that you are aggressive, an alcoholic or engage in aggressive behaviour, it just may mean that you have a higher probability of having a problem than someone else (Lewis, 2014).

|

If Henry regularly behaved as he did at the bar with his friends, it would be evident that he is suffering from alcohol-fuelled aggression. |

Alcohol consumption quiz

[edit | edit source]To see if you have a drinking problem, take this short quiz.

If you answered ‘true’ to more than one of these questions, you may be showing the early symptoms of a drinking problem (Spickard, 2005 & Demirkol et al., 2011).

Signs of aggression

[edit | edit source]

Table 3. Signs to lookout for if you are concerned that you are engaging in overly aggressive behaviour.

| Physical changes | Behavioural changes |

|---|---|

| Sweating/perspiring | Loud speech or shouting |

| Clenched teeth or jaws | Pointing or jabbing with the finger |

| Shaking | Swearing/verbal abuse |

| Muscle tension | Over-sensitivity to what is being said |

| Clenched fist | Standing too close |

| Rapid breathing/sharp drawing in of breath | Aggressive posture |

| Staring eyes | Tone of voice |

| Restlessness/fidgeting | Problem with concentration |

| Flushed face or extreme paleness of face | Stamping feet |

| Change in health of a family member | Banging/ kicking things |

| Rise in pitch of voice | Walking away |

If you took the alcohol quiz and read the table about aggressive physical and behavioural changes and feel both apply to your behaviour, you may be struggling with alcohol-fuelled aggression.

Treatment options

[edit | edit source]A variety of treatment options are available for alcoholism, aggression issues and alcohol-fuelled aggression (McCulloch & McMurran, 2008). These include anger management classes, rehab, pharmacological medication such as mood stabilisers, antidepressants, lithium, beta blockers and cognitive behavioural therapy (McMurran, 2013 & McCulloch & McMurran, 2008).

Further information regarding the treatment options for alcoholism, aggressive behaviour and alcohol-fuelled aggression can be found under external links.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The purpose of this book chapter was to explain and understand the relationship between alcohol and aggression. By drawing upon definitions, relevant theories (disinhibition theory, social learning theory and general aggression model), empirical studies, and examining three key factors (biological, sexual and cultural) the relationship between alcohol consumption and aggression is analyzed and better understood. One devastating effect of the relationship between alcohol and aggression is alcohol-fuelled aggression. Alcohol-fuelled aggression can result in tragic outcomes, such as one-punch fatalities. By examining the federal and state government's policies and strategies to address these problems, and providing additional measures and suggestions to address them, the aim of this book chapter is to provide information and assistance to individuals (and their family and friends) who may be struggling with alcoholism, aggression and/or alcohol-fuelled aggression.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Neurobiology of aggression (Book chapter, 2010)

- Aggression in the workplace (Book chapter, 2010)

- Aggression (Book chapter, 2013)

- Methamphetamine and aggression (Book chapter, 2014)

- Sexual violence motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

- Cultural differences in aggression (Book chapter, 2014)

- Binge drinking motivation in young people (Book chapter, 2015)

- Alcohol addiction and emotion (Book chapter, 2015)

- Anger and violent behaviour (Book chapter, 2015)

References

[edit | edit source]Babor, T. (2010). Alcohol: No ordinary commodity: Research and public policy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Berkowitz, L. (1974). Some determinants of impulsive aggression: Role of mediated associations with reinforcements for aggression. Psychological Review, 81, 165 .

Bettencourt, B. & Miller, N. (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 422 .

Björkqvist, K. (1994). Sex differences in physical, verbal, and indirect aggression: A review of recent research. Sex roles, 30, 177-188.

Blair, R. J. R. (2004). The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behavior. Brain and Cognition, 55, 198-208.

Buckholtz, J. W., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2008). MAOA and the neurogenetic architecture of human aggression. Trends in Neurosciences, 31, 120-129.

Buss, D. M., & Dedden, L. A. (1990). Derogation of competitors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7 (3), 395-422.

Cadoret, R., Leve, L. & Devor, E. (1997). Genetics of aggressive and violent behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20 (2), 301-322.

Carré, J., Putnam, S., & McCormick, C. (2009). Testosterone responses to competition predict future aggressive behaviour at a cost to reward in men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34 (4), 561-570. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.018

Demirkol, A., Haber, P. & Conigrave, K. (2011). Problem drinking: Detection and assessment in general practice. Australian Family Physician, 40 (8), 570-574

Dermen, K. H., & George, W. H. (1989). Alcohol expectancy and the relationship between drinking and physical aggression. The Journal of psychology, 123 (2), 153-161.

Eckardt, M., File, S., Gessa, G., Grant, K., Guerri, C., Hoffman, P. & Tabakoff, B. (1998). Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on the central nervous system. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 22, 998-1040. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03695.x

Giancola, P. R., Josephs, R. A., Parrott, D. J., & Duke, A. A. (2010). Alcohol myopia revisited clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5 (3), 265-278.

Goldstein, J. (2013). Social psychology. New York: Academic Press Inc.

Gustafon, R. (1994) Alcohol and aggression. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 21 (3), 41–80.

Krug, E., Mercy, J., Dahlberg, L. & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The lancet, 360 (9339), 1083-1088.

Iwamoto, D., Cheng, A., Lee, C., Takamatsu, S., & Gordon, D. (2011). “Man-ing” up and getting drunk: The role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addictive Behaviors, 36 (9), 906-911. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.005

Inglehart, R. & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, J. & Leff, M. (1999). Children of substance abusers: Overview of research findings. Paediatrics, 103 (Supplement 2), 1085-1099.

Knowles, G. (2015, August 7). One punch death toll is much higher. The West Australian. Retrieved from: https://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/wa/a/29201578/one-punch-death-toll-is-much-higher/

Lewis, D. (2014, January 1). Why does alcohol make some people violent? ABC News. Retrieved from: http://www.abc.net.au/health/thepulse/stories/2014/01/30/3934877.htm

Lloyd, P. (2010. August 23). Alcohol costs Australia 36billion/year report. ABC News. Retrieved from: http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2010/s2991299.htm

Loeber, S., Duka, T., Welzel, H., Nakovics, H., Heinz, A., Flor, H., & Mann, K. (2009). Impairment of cognitive abilities and decision making after chronic use of alcohol: The impact of multiple detoxifications. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 44 (4), 372-381. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agp030

Margetts, J. (2015, August 27). Shaun McNeil sentenced to a maximum 10 years in prison over one punch death of Daniel Christie. ABC News. Retrieved from: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-27/shaun-mcneil-jailed-over-one-punch-death-of-daniel-christie/6728418

McCulloch, A. & McMurran, M. (2008). Evaluation of a treatment programme for alcohol‐related aggression. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 18 (4), 224-231. doi:10.1002/cbm.700

McMurran, M. (2013). Individual-level interventions for alcohol-related violence: Expanding targets for inclusion in treatment programs. Journal of Criminal Justice, 41 (2), 72-80.

McNaught, A. & Wilkinson, A. (1997) IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. doi:10.1351/goldbook.

Midford, R. (2005). Australia and alcohol: Living down the legend. Addiction.

Miller, N. (1941). The frustration-aggression hypothesis. Psychological Review, 48 , 337-342.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical psychology review, 24 (8), 981-1010.

NSW Government, 2015. Alcohol and drug-fuelled violence initiatives. Retrieved from http://www.nsw.gov.au/alcohol-and-drug-fuelled-violence-initiatives

Oei, T. & Baldwin, A. (1994). Expectancy theory: a two-process model of alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55 (5), 525-534.

Olding, R. (2015, April 16) Lockout laws: assaults down 40% in city, but no evidence we are drinking less. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from: http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/lockout-laws-assaults-down-40-per-cent-in-sydney-city-but-no-evidence-we-are-drinking-less-20150416-1mm70x.html

Quigley, B. M., & Leonard, K. E. (2006). Alcohol expectancies and intoxicated aggression. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11 (5), 484-496. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2006.01.008

Spickard, A. (2005). Dying for a Drink: What You and Your Family Should Know About Alcoholism. Tennessee, America: Thomas Nelson Inc.

Widom, C. S., & Brzustowicz, L. M. (2006). MAOA and the “Cycle of violence:” childhood abuse and neglect, MAOA genotype, and risk for violent and antisocial behavior. Biological Psychiatry, 60 (7), 684-689. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.039

Wilsnack, S. & Wilsnack, R. (2002). International gender and alcohol research: Recent findings and future directions. Alcohol Research & Health : The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 26 (4), 245.

Wilson, J. & Nagoshi, C. (1988). Adult children of alcoholics: Cognitive and psychomotor characteristics. British Journal of Addiction, 83 (7), 809-820.

Wood, W. & Eagly, A. (2002). A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological bulletin, 128 (5), 699.

Young, S. & Kopelman, M. (2009). Forensic neuropsychology in practice. Oxford University Press Inc. New York.

External links

[edit | edit source]Treating and managing a drinking problem

[edit | edit source]Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options

Treating and managing aggressive behaviour

[edit | edit source]Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options

Treating and managing alcohol-fuelled aggression

[edit | edit source]Information about treatment options

Information about treatment options