Introduction to psychology/Psy102/Tutorials/Motivation

Appearance

Motivation

| Subject classification: this is a psychology resource. |

| Resource type: this resource contains a tutorial or tutorial notes. |

| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

This is an introductory 2 hour psychology 102 tutorial about motivation. It invites students to explore their own motivational tendencies, including their motivation to attend university, and to critique some well-known motivational theories/models.

Goals

[edit | edit source]- Examine own and typical university student motivations

- Explore some well-known motivational theories/models

- Understand relationship-oriented vs. task-oriented leadership styles - and situational leadership

- Explore the role of similarity as a motivation in match-making and sexuality

What you will need

[edit | edit source]- Copy (per student) of the University Student Motivation survey

- Copy (per student) of the University Student Outcomes survey

- Copy (per student) of the Motivational Needs Questionnaire

- Copy (per student) of Rotter's Locus of Control scale and the scoring sheet

- Copy (per student) of a pieces with a number from 1 to 6 and a rubber band (per student)

- Copy (per student) of the LPC (leadership) scale

What is motivation? (5 mins)

[edit | edit source]- Ask students to try to define motivation - in their own words.

- For some ideas, see the Motivation lecture notes

University student motivation (20 mins)

[edit | edit source]- An effective way of introducing the nature and diversity of human motivation is to ask:

- “Why do students go to ufni?” - or more specially -

- "Why are you at university?"the reason I am at university is to gain knowledge ,skill and get to know what I will do in future ,the type of job i will work on .The other thing is to improve my countries economy ,that will make the economy grow

- Develop a class mind-map of responses to focus on the main motivational themes. Encourage honesty - why are they really at university? (Answers are likely to cover a wide range of human motives.) With a bit of prompting sometimes, students usually come up with something like the following:

- Career/Qualifications - for the degree, so I can get a better job etc.

- Self-Exploration/Learning - for the learning, curiousity, knowledge-seeking etc.

- Social Opportunities - to meet people, make and explore friendships, enjoy social enviroment

- Altruism - to become better able to help people, help society, help the planet etc.

- Social Pressure - expectations of family, friends, society etc.

- Rejection of Alternatives - better option than doing nothing, working etc. (Note: Factor analytic research by Neill (2008) has not found psychometric support for this factor, but it has for the other factors).

- Have students complete the University Student Motivation survey, then plot their responses against the average results for University of Canberra students (as collected by the third year Survey research and design in psychology in 2008).

- Share and discuss motivational profiles with partners and as a class - ask who was noticeably higher or lower on any particular motivation dimensions

- Next, have students complete the University Student Outcomes survey. Students should then plot the scores for the first five items on to their graph (e.g., using a different colour).

- According to a functionalist perspective on motivation (e.g., see volunteer motivation), a good match between motivations and outcomes leads to satisfaction and retention (or intention to continue), whereas a poor match between motivations and outcomes leads to low satisfaction and risk of drop-out.

- The take-home messages from this "functional motivation" exercise are:

- Our motivations can be multiple and complex

- The match between our motivations and outcomes is theorised to predict satisfaction and satisfaction is theorised to predict our likelihood to continue.

Motivational theories

[edit | edit source]Let's now consider some of the main motivational theories proposed within psychology.

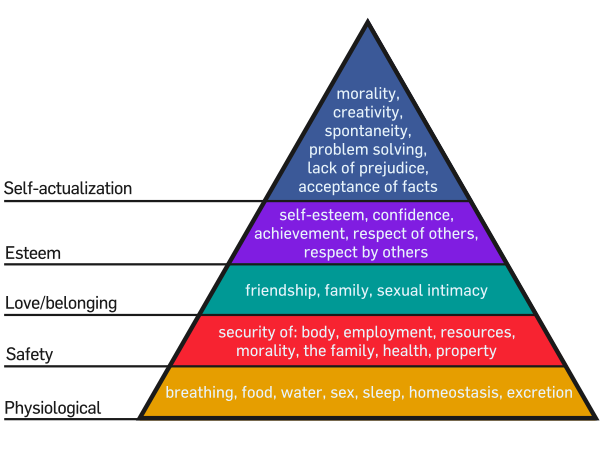

Maslow's hierarchy of needs (10 mins)

[edit | edit source]

- Ask students to explain Maslow's hierarchy of needs - draw it up on the board as you go

- What are the needs? Examples?

- What are the main principles?

- That we need to (largely) satisfy the lower needs before focusing on higher needs

- That when the lower needs are satisfied, that we naturally aspire to the higher needs

- Ask students to determine where each of the main reasons for going to uni would fit - does the model seem to apply as a useful way to understand their university and other life motivations?

- What are the criticisms?

- Exceptions: Maslow recognized that while the order of the hierarchy holds for most people, there are exceptions. Martyrs, for example, sacrifice life itself for an ideal. For some people, the need for respect must be satisfied before they can enter into a love relationship.

- Soft boundaries: Maslow also recognized that a given motive did not have to be 100 percent satisfied before we turn to a higher need. Our needs, Maslow said, are only partially satisfied at any given moment. He estimated that for the average American, 85 percent of physiological needs, 70 percent of safety needs, 50 percent of belongingness and love needs, 40 percent of self-esteem needs, and 10 percent of self-actualization needs are satisfied. Still, it makes sense that how well lower needs are met determines how much those needs influence our behavior.

- Cultural variation: Maslow noted that the means of satisfying a particular need varied across cultures. In our society, a person may win respect from others by becoming a doctor. In another society, respect may come from being a successful hunter or farmer.

- Causes of behaviour: Maslow did not actually believe that any given behavior is motivated by a single need; he contended that behavior is the result of multiple motivations. Sexual behavior, for example, may be motivated by the need for sexual release, by a need to win or express affection, by a sense of conquest or mastery, and/or by a desire to feel feminine or masculine.

- You might conclude your discussion of Maslow’s theory by noting that he described another set of human needs that does not appear in the hierarchy: the cognitive needs, or the needs to know and to understand. These needs are expressed in the need to analyze or reduce things to their basic elements; the need to experiment, to “see what will happen if I do this”; the need to explain, to construct a personal theory that will make sense of the events of one’s world. Maslow even suggested that these needs form their own smaller hierarchy. For example, the need to know is more important than the need to understand. The cognitive needs appear early in life and are seen in a child’s natural curiosity. Failure to meet these needs (because parents and schools sometimes teach a child to inhibit this spontaneous curiosity) can inhibit the development and full functioning of the individual. (Burger, 2004[1]; Schultz & Schultz, 2005[2])

- You could alternatively conclude by pointing to alternative need models, such as fundamental human needs (Max-Neef et al.)

McClelland's theory of needs (15 mins)

[edit | edit source]- McClelland theorised that people were predominantly driven by one of three key needs (achievement, power or affiliation). Discuss: Need theory - [1]

- Complete and score the Motivational Needs Questionnaire (a self-report measure of MClelland's needs[2]). This assessment measures the relative extent to which individuals are motivated by achievement, power or affiliation. The questionnaire is followed by an answer key to determine which best describes how the individual is motivated.

- Ask for a show of hands as to who is most motivated by each of the three motivations.

- Discuss: Can motivation by measured through self-report? What about projective tests (e.g., the Thematic Apperception Test) as a measure of motivation. What are the pros and cons of projective vs. standardised psychometric testing?

Locus of control (15 mins)

[edit | edit source]- Invite students to complete Rotter's (1966) 29-item Locus of Control scale questionnaire. For each item, students should choose the most preferred of the two options. They may find this difficult (e.g., they may disagree with both), but emphasise that they should pick the one the least disagree with.

- Hand out the scoring sheets and ask students to score their own responses.

- Draw a histogram up and the board (ranging from 0 (External) to 23 (Internal)) and ask students their scores and plot them - a normal(ish) curve is usually evident.

- Explain theoretical background and interpretation of the locus of control construct, including:

- What influences or is associated with locus of control?

- Previous experience (of having control or not)

- Age (we tend to become more internal over time)

- Gender (males tend to be more internal)

- Culture (Western culture tends to be more internal))

- Emphasise that it is not as simple as "internal = good", "external = bad" e.g., this will also depend on whether one has the skills, motivation, and power to control what one feels responsible for; high internality with low degree of self-efficacy can lead to anxiety/neuroticism; high externality can be quite adaptive e.g., during palliative care). In general, though, moderate to high internality is associated with better achievement and performance outcomes. For more info, see locus of control.

- What influences or is associated with locus of control?

Leadership style (15 mins)

[edit | edit source]- Leadership styles can be understood as an individual motivational difference. A common distinction is between task- and people-oriented leadership. Fiedler (1976[3]) believes that this style is a relatively fixed part of one’s personality, and is therefore difficult to change. This leads him to his contingency views, which suggest that the key to leadership success is finding (or creating) good “matches” between style and situation. For more info, see Fieldler contingency model - least preferred co-worker (LPC) scale.

- Ask students to complete the least preferred co-worker (LPC) scale. They calculate their scores by adding the numbers they have circled for each of the adjective pairs.

- Fiedler believes that this style is a relatively fixed part of one’s personality, and is therefore difficult to change. This leads Fiedler to his contingency views, which suggest that the key to leadership success is finding (or creating) good “matches” between style and situation.

- LPC score interpretations:

- Score of < 64: A "task-oriented" leader ccording to Fiedler, a person who describes his or her LPC in very negative terms (a score of less than 57) is a task-motivated person. The completion of the task is of such importance to this person that it shapes his or her perception of all other traits. In effect, the person says, “if I cannot work with you, then you can't be any good in other respects”.

- Score of > 73: A "relationship-oriented" leader who believes that “getting a job done is not everything. Even though I can’t work with you, you may still be friendly, relaxed, interesting etc.”.

- Score of 65 - 72: A mixture of both; socially independent, less concerned about the way people evaluate them, and maybe less eager to take the leadership role or may have a combination of the two motivational patterns.

- Discuss with the students whether they think their score is an accurate representation of their style.

- Ask students when a task-oriented or relationship-oriented leadership style might be better? (Hint: The key, according to situational leadership, is to be flexible, and to match one's style to the situation)

- task-oriented tends to be more effective when the leader is on either very good or very bad terms with group members, when the task is either clearly structured or clearly unstructured, or when the leader has a position of very high or very low authority and power;

- relationship-oriented tends to be best when there are moderately good or poor relations between the leader and group members, when the task is somewhat structured, and when the leader has intermediate power or authority.

The pairing game (20 mins)

[edit | edit source]- A class activity to illustrate the matching phenomenon and to explore issues concerning mate selection, social exchange, and related psychological concepts.[4][5]

- Hand out rubber bands (need to be reasonable size) and ask to students to place one around their head), and to hold their rubber band out so that a random number (between 1 and 6) can be places on their forehead (then they let the rubber band go to keep it there).

- The instructor can join in (have someone else allocate a number).

- Others should be able to see the number, but a person cannot see their own number.

- The goal is to pair off with another student with as high a value as possible.

- The simulation illustrates the "similarity matching hypothesis" - that similarity attracts more so than opposites attract. This occurs even in the absence of knowledge of one's own value and merely by seeking the highest value possible in a partner.

- Jim Friedrich reports that he uses this activity and then scatterplots the results: "I simply have my pairs that have emerged from the game arbitrarily designate a "Partner A" and a "Partner B"; then each pair gets to plot their coordinates with Partner A on the X axis and Partner B on the Y. There's always a very nice scatterplot, as the demo itself produces pretty good matching. Even medium size correlations of r = .5 tend to look pretty vague in small-N scatterplots, but the patterns jump right out whenever I do this (with or without the actual statistical calculation)."

- In general, people are more likely to match up with partners who are similar (rather than dissimilar) with respect to:

- Physical attractiveness

- Social class

- Race

- Intelligence

- For more info, see interpersonal attraction

See also

[edit | edit source]- Cultural differences in sexuality

- Motivation

- Motivation and emotion

- Motivational theories

- Social psychology (psychology)/Tutorials

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Burger, J. (2004). Personality (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- ↑ Schultz, D., & Schultz, S. (2005). Theories of personality (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- ↑ Fiedler, F. E., Chemers, M. M., & Mahar, L. (1976). Improving leadership effectiveness: The leader match concept. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ↑ Jonathan Mueller Activities

- ↑ Ellis, Bruce J; Kelley, Harold H. (1999). The pairing game: A classroom demonstration of the matching phenomenon. Teaching of Psychology, 26, 118-121.