WikiJournal of Medicine/An overview of Lassa fever: Difference between revisions

m ce Tag: 2017 source edit |

No edit summary |

||

| (49 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Article info |

{{Article info |

||

| journal = WikiJournal of Medicine |

| journal = WikiJournal of Medicine |

||

| toc=2 |

|||

| last1 = Musa{{efn|Sir Muhammad Sanusi Specialist Hospital, Kano}}{{efn|Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria}}{{efn|Islamic Medical Association of Nigeria}} |

| last1 = Musa{{efn|Sir Muhammad Sanusi Specialist Hospital, Kano}}{{efn|Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria}}{{efn|Islamic Medical Association of Nigeria}} |

||

| first1 = Abdulmutalab |

| first1 = Abdulmutalab |

||

| orcid1 = 0000-0002-9319-198X |

| orcid1 = 0000-0002-9319-198X |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| affiliation1 = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| keywords = Lassa fever, Lassa virus, public health, viral hemorrhagic fever |

| keywords = Lassa fever, Lassa virus, public health, viral hemorrhagic fever |

||

| submitted = 2018-09-25 |

| submitted = 2018-09-25 |

||

| accepted = 15 June 2019 |

| accepted = 15 June 2019 |

||

| doi = 10.15347/wjm/2019.002 |

| doi = 10.15347/wjm/2019.002 |

||

| abstract = Lassa fever is a [[w:Viral_hemorrhagic_fever|viral hemorrhagic fever]] caused by [[w:Lassa virus|Lassa virus]] |

| abstract = Lassa fever is a [[w:Viral_hemorrhagic_fever|viral hemorrhagic fever]] caused by [[w:Lassa virus|Lassa virus]], a negative-sense single stranded RNA virus of the ''[[w:Arenavirus|Arenaviridae]]'' family.<ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Oti|first=Victor B.|date=2018-11-05|title=A Reemerging Lassa Virus: Aspects of Its Structure, Replication, Pathogenicity and Diagnosis|url=https://www.intechopen.com/books/current-topics-in-tropical-emerging-diseases-and-travel-medicine/a-reemerging-lassa-virus-aspects-of-its-structure-replication-pathogenicity-and-diagnosis|journal=Current Topics in Tropical Emerging Diseases and Travel Medicine|language=en|doi=10.5772/intechopen.79072}}</ref> In most cases Lassa virus infection is asymptomatic (presenting no symptom).<ref name=":4" /> When symptomatic it is characterized by mild acute febrile disease to a chronic fatal disease with severe [[w:Toxemia|toxaemia]], [[w:Capillary_leak_syndrome|Capillary leak]], [[w:Bleeding|hemorrhagic situations]], [[w:Shock_(circulatory)|shock]] and [[w:Multiple_organ_dysfunction_syndrome|multiple organ failure]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Monath|first=T. P.|last2=Casals|first2=J.|date=1975|title=Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/|journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization|volume=52|issue=4-6|pages=707–715|issn=0042-9686|pmc=PMC2366641|pmid=1085225}}</ref> Early diagnosis of Lassa fever is very important because of the transmissibility of infection, the need for potent isolation of infected persons and for containing potentially infectious specimens during laboratory testing.<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Monath|first=T. P.|last2=Casals|first2=J.|date=1975|title=Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/|journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization|volume=52|issue=4-6|pages=707–715|issn=0042-9686|pmc=PMC2366641|pmid=1085225}}</ref> |

||

Lassa fever was first elucidated in the 1950s, but the virus was not recognized until 1969 when it infected 2 missionary Nurses in Lassa town [[w:Borno_State|Borno State]], [[w:North_East_(Nigeria)|Northeastern Nigeria]].<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

Approximately 80% of infected persons are [[w:Asymptomatic|asymptomatic]]. |

Approximately 80% of infected persons are [[w:Asymptomatic|asymptomatic]]. Rodents of [[w:Mastomys|''Mastomys'']] genus, often known as the [[w:Natal_multimammate_mouse|Natal multimammate rat (or mouse)]] or common African rat are the reservoir of Lassa virus.<ref name=":4" /> When the rodents become infected with Lassa virus, they infect humans through their urine and faeces, but remain unharmed.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

Because of its similarities with other febrile diseases, (e.g. malaria, typhoid, [[w:Ebola virus disease|Ebola hemorrhagic fever]] etc.), early detection is difficult. Thus when |

Because of its similarities with other febrile diseases, (e.g. malaria, typhoid, [[w:Ebola virus disease|Ebola hemorrhagic fever]] etc.), early detection is difficult. Thus when persons have persistent fever not responding to normal conventional therapies, they should be screened for other possible causes (especially in [[w:Endemic_(epidemiology)|endemic]] regions). When the presence of Lassa fever is established in a community, immediate isolation of infected individuals, screening, standard infection prevention and control practices and meticulous [[w:Contact_tracing|contact tracing]] can halt outbreaks.<ref name=":4" /> Treatment involves supportive measures and early use of the antiviral drug ribavirin. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

== Pathophysiology == |

== Pathophysiology == |

||

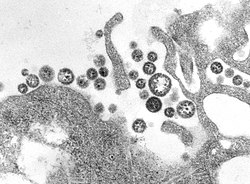

| ⚫ | {{Main|w:Lassa virus}}Lassa virus is a single-stranded negative sense [[w:RNA_virus|RNA virus]] '''(Figure 1)'''.<ref name=":1" /> The transmission of Lassa virus to humans can occur through direct contact and [[w:Aerosol|aerosols]] generated from the urine or feces of an infected rodent<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Hallam|first=Hoai J.|last2=Hallam|first2=Steven|last3=Rodriguez|first3=Sergio E.|last4=Barrett|first4=Alan D. T.|last5=Beasley|first5=David W. C.|last6=Chua|first6=Arlene|last7=Ksiazek|first7=Thomas G.|last8=Milligan|first8=Gregg N.|last9=Sathiyamoorthy|first9=Vaseeharan|date=2018-03-20|title=Baseline mapping of Lassa fever virology, epidemiology and vaccine research and development|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5861057/|journal=NPJ Vaccines|volume=3|doi=10.1038/s41541-018-0049-5|issn=2059-0105|pmc=5861057|pmid=29581897}}</ref>. Natal multimammate rats shed the virus in urine and droppings, direct contact with these excreta, through touching soiled objects, eating contaminated food, or exposure to open cuts or [[w:Sore|sores]], can lead to infection.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/lassa/transmission/index.html|title=Transmission of Lassa Fever|date=2019-03-06|website=www.cdc.gov|language=en-us|access-date=2019-04-09}}</ref> There have been reports of sexual transmission of Lassa fever but it is rare.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Oshin|first=Babafemi A.|date=2019-04-09|title=Rat eating, sexual transmission and the burden of Lassa fever disease|url=https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/rat-eating-sexual-transmission-and-burden-lassa-fever-disease|language=en}}</ref> High [[w:Serum|serum]] [[w:Viral_load|virus titres]], combined with disseminated replication in tissues and absence of [[w:Neutralizing_antibody|neutralizing antibodies]] (immuno-compromisation), lead to the development of Lassa fever.<ref name=":1" /> However, an intact and active immune response is protective against developing symptoms by mounting the early innate immune response in order to prevent further infection and virus growth, which in turn attenuates humoral and cell-mediated immunity.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Zapata|first=Juan Carlos|last2=Medina-Moreno|first2=Sandra|last3=Guzmán-Cardozo|first3=Camila|last4=Salvato|first4=Maria S.|date=2018-10-28|title=Improving the Breadth of the Host’s Immune Response to Lassa Virus|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6313495/|journal=Pathogens|volume=7|issue=4|doi=10.3390/pathogens7040084|issn=2076-0817|pmc=6313495|pmid=30373278}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Brosh-Nissimov|first=Tal|date=2016-04-30|title=Lassa fever: another threat from West Africa|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5330145/|journal=Disaster and Military Medicine|volume=2|doi=10.1186/s40696-016-0018-3|issn=2054-314X|pmc=5330145|pmid=28265442}}</ref> Due to limited data on Lassa fever, the immune responses against it and its pathogenesis are poorly understood.<ref name=":2" /> As such, it is not well understood how viral infection leads to sepsis-like symptoms, cytokine storms or bacterial co-infection.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lin|first=Gu-Lung|last2=McGinley|first2=Joseph P.|last3=Drysdale|first3=Simon B.|last4=Pollard|first4=Andrew J.|date=2018-09-27|title=Epidemiology and Immune Pathogenesis of Viral Sepsis|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6170629/|journal=Frontiers in Immunology|volume=9|doi=10.3389/fimmu.2018.02147|issn=1664-3224|pmc=6170629|pmid=30319615}}</ref><ref>{{Cite_patent|invent1=Cunningham J|invent2= Lee K|invent3= Ren T|invent4= Chandran K|number=US9193705B2|country = USA|title=Small molecule inhibitors of ebola and lassa fever viruses and methods of use|url=https://patents.google.com/patent/US9193705B2/en|date=2011-09-01|accessdate=2019-04-09}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Lassa virus is a single-stranded negative sense [[w:RNA_virus|RNA virus]] '''(Figure 1)'''.<ref name=":1" /> The transmission of Lassa virus to humans |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{fig|1 |

|||

|Lassa virus.JPG |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

There are several pathways involved in the pathogenesis of Lassa fever.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":9" /> Similar to the pathogenesis of [[w:Sepsis|sepsis]], induction of uncontrolled [[w:Cytokine|cytokine]] expression can be triggered by Lassa virus infection.<ref name=":1" /> Systemic viral-induced immunosuppression can also be implicated in severe Lassa virus infections.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Two immunoglobulins ([[w:Immunoglobulin_M|IgM]] and [[w:Immunoglobulin_G|IgG]] antibody [[w:Isotype_(immunology)|isotypes)]] are produced in Lassa virus infected person, because both can be present in [[w:Viremia|viremic]] persons, and possibly only non-neutralizing antibodies are produced early in the infectious process, this makes the antibodies to remain present in a-lot of persons across West Africa, while late antibodies are protective because they neutralize the virus.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Yun|first=Nadezhda E.|last2=Walker|first2=David H.|date=2012-10-09|title=Pathogenesis of Lassa Fever|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3497040/|journal=Viruses|volume=4|issue=10|pages=2031–2048|doi=10.3390/v4102031|issn=1999-4915|pmc=PMC3497040|pmid=23202452}}</ref><ref name=":9">{{Cite web|url=https://vhfc.org/diseases/lassa/|title=Lassa|website=Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Consortium|language=en-US|access-date=2019-04-09}}</ref> Early antibodies are not neutralizing making them resistant; this is because proteinous surface of the Lassa virus is protected by under-processed [[w:Glycan|glycans]] form with structurally distinct clusters.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Crispin|first=Max|last2=Bowden|first2=Thomas A.|last3=Strecker|first3=Thomas|last4=Huiskonen|first4=Juha T.|last5=Moser|first5=Felipe|last6=Li|first6=Sai|last7=Seabright|first7=Gemma E.|last8=Allen|first8=Joel D.|last9=Raghwani|first9=Jayna|date=2018-07-10|title=Structure of the Lassa virus glycan shield provides a model for immunological resistance|url=https://www.pnas.org/content/115/28/7320|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|language=en|volume=115|issue=28|pages=7320–7325|doi=10.1073/pnas.1803990115|issn=0027-8424|pmid=29941589}}</ref><ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last=Robinson|first=James E.|last2=Hastie|first2=Kathryn M.|last3=Cross|first3=Robert W.|last4=Yenni|first4=Rachael E.|last5=Elliott|first5=Deborah H.|last6=Rouelle|first6=Julie A.|last7=Kannadka|first7=Chandrika B.|last8=Smira|first8=Ashley A.|last9=Garry|first9=Courtney E.|date=2016-05-10|title=Most neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies target novel epitopes requiring both Lassa virus glycoprotein subunits|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4866400/|journal=Nature Communications|volume=7|doi=10.1038/ncomms11544|issn=2041-1723|pmc=4866400|pmid=27161536}}</ref> |

||

The main underlying feature of Lassa fever is that the vascular bed is attacked by the virus, with resultant micro-vascular damage and changes in [[w:Vascular_permeability|vascular permeability]]. Secondary results of capillary leakage and reduced effective circulating blood volume may include increase in sympathetic tone, local tissue [[w:Acidosis|acidosis]], [[w:Anoxia|anoxia]] and further reduction in tissue blood flow, thus generating the shock syndrome. Overall it is apparent that liver damage occurs in almost all cases of Lassa fever in varying degrees,<ref name=":1" /> while vascular damage and hemorrhaging tends to be associated more with the New World [[w:Arenavirus|arenaviruses]] in South America.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Brisse|first=Morgan E.|last2=Ly|first2=Hinh|date=2019-03-13|title=Hemorrhagic Fever-Causing Arenaviruses: Lethal Pathogens and Potent Immune Suppressors|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6424867/|journal=Frontiers in Immunology|volume=10|doi=10.3389/fimmu.2019.00372|issn=1664-3224|pmc=6424867|pmid=30918506}}</ref> |

|||

The main underlying feature of Lassa fever is that the vascular bed is attacked by the virus, with resultant micro-vascular damage and changes in [[w:Vascular_permeability|vascular permeability]].<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":12">{{Cite journal|last=Brisse|first=Morgan E.|last2=Ly|first2=Hinh|date=2019-03-13|title=Hemorrhagic Fever-Causing Arenaviruses: Lethal Pathogens and Potent Immune Suppressors|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6424867/|journal=Frontiers in Immunology|volume=10|doi=10.3389/fimmu.2019.00372|issn=1664-3224|pmc=6424867|pmid=30918506}}</ref> Secondary resultant of capillary leak syndrome and reduced blood volume may include increased cardiac activity, local tissue [[w:Acidosis|acidosis]], [[w:Anoxia|anoxia]] and reduction in blood circulation, thus leading to the shock syndrome.<ref name=":12" /> Generally it is clear that liver damage occurs in almost all cases of Lassa fever in different levels.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | Pre–renal acute kidney failure, [[w:Lactic_acidosis|lactic acidaemia]], [[w:Hyperkalemia|hyperkalaemia]] and reduced perfusion and oxygenation of vital tissues follows and progress to fatal outcome. The secondary effects of micro-vascular damage include alterations in pulmonary function due to several mechanisms.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Monath|first=T. P.|last2=Casals|first2=J.|date=1975|title=Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/|journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization|volume=52|issue=4-6|pages=707–715|issn=0042-9686|pmc=PMC2366641|pmid=1085225}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Pre–renal acute kidney failure, [[w:Lactic_acidosis|lactic acidaemia]], [[w:Hyperkalemia|hyperkalaemia]] and reduced perfusion and oxygenation of vital tissues follows and progress to fatal outcome.<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":13" /> The secondary effects of micro-vascular damage include alterations in pulmonary function due to several mechanisms.<ref name=":13">{{Cite journal|last=Monath|first=T. P.|last2=Casals|first2=J.|date=1975|title=Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/|journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization|volume=52|issue=4-6|pages=707–715|issn=0042-9686|pmc=PMC2366641|pmid=1085225}}</ref> |

||

== Frequency (epidemiology) == |

== Frequency (epidemiology) == |

||

| Line 40: | Line 39: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

Estimating the true incidence and mortality of Lassa Fever is extremely difficult due to the non-specific clinical presentation; |

Estimating the true incidence and mortality of Lassa Fever is extremely difficult due to the non-specific clinical presentation; poor surveillance systems; sizeable human migration, uneasy landscape and lack of standard laboratory confirmation.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780124169753000042|title=Emerging Infectious Diseases|last=Grant|first=Donald S.|last2=Khan|first2=Humarr|last3=Schieffelin|first3=John|last4=Bausch|first4=Daniel G.|date=2014|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=9780124169753|pages=37–59|language=en|doi=10.1016/b978-0-12-416975-3.00004-2}}</ref> |

||

Nevertheless, Lassa fever frequently infects people in [[w:West_Africa|West Africa]] '''(Figure 2)''' with approximately 80% being asymptomatic. Studies show up to 300,000 – 500,000 cases annually and about 5,000 deaths. Lassa fever is endemic in parts of West Africa, |

Nevertheless, Lassa fever frequently infects people in [[w:West_Africa|West Africa]] '''(Figure 2)''' with approximately 80% being asymptomatic.<ref name=":0" /> Studies show up to 300,000 – 500,000 cases annually and about 5,000 deaths. Lassa fever is endemic in some parts of West Africa, which includes [[w:Sierra_Leone|Sierra Leone]], [[w:Liberia|Liberia]], [[w:Ghana|Ghana]], [[w:Guinea|Guinea]] and Nigeria.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Behrens|first=Ron|last2=Houlihan|first2=Catherine|date=2017-07-12|title=Lassa fever|url=https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j2986|journal=BMJ|language=en|volume=358|pages=j2986|doi=10.1136/bmj.j2986|issn=1756-1833|pmid=28701331}}</ref> |

||

There |

There have been reports of Lassa fever in neighboring countries; In 2016, two cases were reported in [[w:Togo|Togo]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.who.int/csr/don/23-march-2016-lassa-fever-togo/en/|title=Lassa Fever – Togo|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> and 6 confirmed cases in [[w:Benin|Benin]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.who.int/csr/don/19-february-2016-lassa-fever-benin/en/|title=Lassa Fever – Benin|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> In the [[w:US|US]] on 25 May 2015, there was a confirmed case in a US returnee from Liberia.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/csr/don/28-may-2015-lassa-fever-usa/en/|title=Lassa Fever – United States of America|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> There have been imported cases of Lassa fever in European countries including [[w:Sweden|Sweden]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.who.int/csr/don/8-april-2016-lassa-fever-sweden/en/|title=Lassa fever – Sweden|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> [[w:Germany|Germany]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.who.int/csr/don/27-april-2016-lassa-fever-germany/en/|title=Lassa Fever – Germany|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> [[w:Netherlands|The Netherlands]]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/csr/don/2000_07_26/en/|title=2000 - Imported case of Lassa fever in The Netherlands - Update|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> and the [[w:United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Ireland|United Kingdom]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_02_10a/en/|title=Imported case of Lassa fever in United Kingdom|website=WHO|access-date=2019-01-11}}</ref> all of which where imported from West Africa.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/lassa_fever/en/|title=WHO {{!}} Lassa fever|website=WHO|access-date=2019-06-22}}</ref> |

||

===Outbreak in Nigeria=== |

===Outbreak in Nigeria=== |

||

In [[w:Nigerians|Nigeria]], |

In [[w:Nigerians|Nigeria]], from 1 January to 20 May 2018, 1940 suspected cases have been reported from 21 states.<ref name=":3" /> Of these, 431 were confirmed positive, 10 are probable, 1495 negative.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/sitreps/?cat=5&name=An%20update%20of%20Lassa%20fever%20outbreak%20in%20Nigeria|title=Nigeria Centre for Disease Control|website=www.ncdc.gov.ng|access-date=2019-04-09}}</ref><ref name=":4" /> A total of 6489 contacts have been identified in 20 states since January 2019 to March 2019, a total of 2034 suspected cases have been reported from 21 states.<ref name=":3" /> Of these, 526 were confirmed positive, 15 probable and 1693 negative (not a case).<ref name=":3" /> out of these, 17 health care workers have been affected in six states with four deaths (case fatality rate= 29%).<ref name=":3" /> |

||

== |

== Presentation == |

||

Lassa fever has an incubation period of 6 – 21 days.<ref name=":4" /> The onset of lassa fever is usually asymptomatic and when symptomatic it is usually subtle, starting with fever and malaise. When it progresses, it presents with sore throat, headache, achy muscle, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, diarrhea, cough, and abdominal pain.<ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/1609|title=Lassa fever - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment|last=|first=|date=|website=bestpractice.bmj.com|publisher=BMJ|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=2019-06-22}}</ref> In critical cases systemic involvement occurs with the following: |

|||

| ⚫ | *Respiratory: [[w:Pleural_effusion|pleural effusion]], [[w:Epistasis|epistaxis]], [[w:Crackles|rales]], [[w:Rhonchi|rhonchi]], [[w:Stridor|stridor]], [[wikipedia:Cough|cough,]] [[w:Wheeze|wheezing]], [[w:Pharyngitis|pharyngitis]], and [[w:Shortness_of_breath|dyspnoea]]<ref name=":13" /><ref name=":20" /> |

||

In severe cases systemic involvement occurs with the following: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Temporary hair loss and [[w:Gait_abnormality|gait interference]] may occur during recovery.<ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Behrens|first=Ron|last2=Houlihan|first2=Catherine|date=2017-07-12|title=Lassa fever|url=https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j2986|journal=BMJ|language=en|volume=358|pages=j2986|doi=10.1136/bmj.j2986|issn=0959-8138|pmid=28701331}}</ref> |

|||

Transient hair loss and [[w:Gait_abnormality|gait disturbance]] may occur during recovery. |

|||

Lassa fever is usually fatal within 14 days of inception<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":19">{{Cite journal|last=Greenky|first=David|last2=Knust|first2=Barbara|last3=Dziuban|first3=Eric J.|date=2018-05-01|title=What Pediatricians Should Know About Lassa Virus|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5970952/|journal=JAMA pediatrics|volume=172|issue=5|pages=407–408|doi=10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5223|issn=2168-6203|pmc=PMC5970952|pmid=29507948}}</ref> |

|||

== Causes and transmission== |

== Causes and transmission== |

||

Lassa virus is [[w:Zoonosis|zoonotic]],<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kafetzopoulou|first=L. E.|last2=Pullan|first2=S. T.|last3=Lemey|first3=P.|last4=Suchard|first4=M. A.|last5=Ehichioya|first5=D. U.|last6=Pahlmann|first6=M.|last7=Thielebein|first7=A.|last8=Hinzmann|first8=J.|last9=Oestereich|first9=L.|date=2019-01-04|title=Metagenomic sequencing at the epicenter of the Nigeria 2018 Lassa fever outbreak|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aau9343|journal=Science|language=en|volume=363|issue=6422|pages=74–77|doi=10.1126/science.aau9343|issn=0036-8075}}</ref> as it spreads specifically from Natal multimammate mice (''Mastomys natalensis''). It is the most |

Lassa virus is [[w:Zoonosis|zoonotic]],<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last=Kafetzopoulou|first=L. E.|last2=Pullan|first2=S. T.|last3=Lemey|first3=P.|last4=Suchard|first4=M. A.|last5=Ehichioya|first5=D. U.|last6=Pahlmann|first6=M.|last7=Thielebein|first7=A.|last8=Hinzmann|first8=J.|last9=Oestereich|first9=L.|date=2019-01-04|title=Metagenomic sequencing at the epicenter of the Nigeria 2018 Lassa fever outbreak|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aau9343|journal=Science|language=en|volume=363|issue=6422|pages=74–77|doi=10.1126/science.aau9343|issn=0036-8075}}</ref> as it spreads specifically from Natal multimammate mice (''Mastomys natalensis'').<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> It is the most prevalent mouse in [[w:Equatorial_Africa|equatorial Africa]], omnipresent in households and consumed as food in some areas.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hussainia|first=Nafiu|last2=Abdulhamid|first2=Abdurrahman|date=2018-01-01|title=Effects of quarantine on transmission dynamics of Lassa fever|url=https://www.ajol.info/index.php/bajopas/article/view/183493|journal=Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences|volume=11|issue=1|pages=397–407–407|issn=2006-6996}}</ref> Infection occurs by exposure to rat excreta directly or indirectly via contaminated food stuffs.<ref name=":5" /> Infection can also occur by inhalation of tiny particles (aerosols) of infected materials, airborne transmission is rare as there is no evidence to support that.<ref name=":4" /> It is possible to acquire infection through broken skin or mucous membranes that is directly exposed to infectious materials, and through rat bites.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> In addition, the virus can also be contracted via contaminated hospital equipment, such as re–used needles and improper sterilization.<ref name=":4" /> The presence of Lassa virus in the semen indicates high risk of sexual transmission but viral load is not enough to cause infection.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Oshin|first=Babafemi A.|date=2019-04-27|title=Rat eating, sexual transmission and the burden of Lassa fever disease|url=https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/rat-eating-sexual-transmission-and-burden-lassa-fever-disease|language=en}}</ref> |

||

== Diagnosis == |

== Diagnosis == |

||

Clinical diagnosis of Lassa fever disease is usually difficult, this is as a result of it vague symptoms.<ref name=":4" /> Lassa fever is hard to differentiate from other febrile diseases e.g. [[w:Malaria|malaria]], [[w:Typhoid_fever|typhoid]], [[w:Influenza|influenza]], relapsing fever, [[w:Leptospirosis|leptospirosis]] and other [[w:Viral_hemorrhagic_fever|hemorrhagic fevers]] e.g. [[w:Yellow_fever|yellow fever]], [[w:Dengue_fever|dengue]], [[W:Marburg virus disease|Marburg]] and [[w:Ebola_virus_disease|Ebola]].<ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lassa-fever|title=Lassa fever|website=www.who.int|language=en|access-date=2019-06-20}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[w:ELISA|Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays]] (ELISAs) can be used to detect specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies or viral antigens in acute serum samples from persons with Lassa fever (it can be detected even in acute phase).<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/679252357|title=Diagnosis and Clinical Virology of Lassa Fever as Evaluated by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, Indirect Fluorescent-Antibody Test, and Virus Isolation|last=Bausch, D. G. Rollin, P. E. Demby, A. H. Coulibaly, M. Kanu, J. Conteh, A. S. Wagoner, K. D. McMullan, L. K. Bowen, M. D. Peters, C. J. Ksiazek, T. G.|publisher=American Society for Microbiology|oclc=679252357}}</ref> |

|||

* [[w:reverse_transcription_polymerase_chain_reaction|Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction]] (RT–PCR) assay can be used in early stage to detect the virus using inactivated virus. it is very helpful in areas where BSL4 laboratories cannot be found especially in west Africa.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Koehler|first=Jeffrey|last2=Raabe|first2=Vanessa|date=2017-06-01|title=Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever|url=https://jcm.asm.org/content/55/6/1629|journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology|language=en|volume=55|issue=6|pages=1629–1637|doi=10.1128/JCM.00170-17|issn=0095-1137|pmid=28404674}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | * [[w:Viral_culture|Virus cultivation]] and identification technique (virus isolation by cell culture). However, this requires 3 – 10 days or longer for definitive identification.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Raabe|first=Vanessa|last2=Koehler|first2=Jeffrey|date=2017-6|editor-last=Kraft|editor-first=Colleen Suzanne|title=Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever|url=http://jcm.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/JCM.00170-17|journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology|language=en|volume=55|issue=6|pages=1629–1637|doi=10.1128/JCM.00170-17|issn=0095-1137|pmc=PMC5442519|pmid=28404674}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Panning|first=Marcus|last2=Emmerich|first2=Petra|last3=Ölschläger|first3=Stephan|last4=Bojenko|first4=Sergiusz|last5=Koivogui|first5=Lamine|last6=Marx|first6=Arthur|last7=Lugala|first7=Peter Clement|last8=Günther|first8=Stephan|last9=Bausch|first9=Daniel G.|date=2010-6|title=Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever, Liberia|url=http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/6/10-0040_article.htm|journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases|volume=16|issue=6|pages=1041–1043|doi=10.3201/eid1606.100040|issn=1080-6040|pmc=PMC3086251|pmid=20507774}}</ref> |

||

* [[w:Blood_culture|Blood cultures]] to differentiate other pathogens (e.g. typhoid)<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kumar|first=Praveen|last2=Kumar|first2=Ruchika|date=2017-3|title=Enteric Fever|url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12098-016-2246-4|journal=The Indian Journal of Pediatrics|language=en|volume=84|issue=3|pages=227–230|doi=10.1007/s12098-016-2246-4|issn=0019-5456}}</ref> and blood smear to differentiate malaria parasite<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kattenberg|first=Johanna H|last2=Ochodo|first2=Eleanor A|last3=Boer|first3=Kimberly R|last4=Schallig|first4=Henk DFH|last5=Mens|first5=Petra F|last6=Leeflang|first6=Mariska MG|date=2011-12|title=Systematic review and meta-analysis: rapid diagnostic tests versus placental histology, microscopy and PCR for malaria in pregnant women|url=https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-10-321|journal=Malaria Journal|language=en|volume=10|issue=1|doi=10.1186/1475-2875-10-321|issn=1475-2875}}</ref> as the virus can present concomitantly with other diseases.<ref name=":19" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | * General biochemical tests such as [[w:Complete_blood_count|full blood count]], [[w:Erythrocyte_sedimentation_rate|erythrocyte sedimentation rate]]; [[w:Hematocrit|hematocrit]] volume (to exclude anemia); white blood cell count (to exclude lymphopenia); [[w:Platelet|platelet]] count (to exclude thrombocytopenia), [[w:Coagulation_testing|coagulation studies]] (to exclude [[w:Coagulopathy|coagulopathies]]) and liver and kidney function tests (serum liver enzymes have been found to be positive clinical markers).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Salvato|first=Maria S.|last2=Lukashevich|first2=Igor S.|last3=Medina-Moreno|first3=Sandra|last4=Zapata|first4=Juan Carlos|date=2018|title=Diagnostics for Lassa Fever: Detecting Host Antibody Responses|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28986826|journal=Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.)|volume=1604|pages=79–88|doi=10.1007/978-1-4939-6981-4_5|issn=1940-6029|pmid=28986826}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The WHO guidelines for the collection, storage, and handling of Ebola virus specimens testing should be adhered to when testing for Lassa virus.<ref name=":11">{{Cite journal|last=Raabe|first=Vanessa|last2=Koehler|first2=Jeffrey|date=06 2017|title=Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28404674|journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology|volume=55|issue=6|pages=1629–1637|doi=10.1128/JCM.00170-17|issn=1098-660X|pmc=5442519|pmid=28404674}}</ref> Thorough adherence to [[w:Biosafety level|biosafety level]] 4 (BSL-4) precautions is pertinent when handling suspected specimens.<ref name=":11" /> However, BSL-4 laboratories are limited worldwide, when not available, samples should be handled in biosafety level 2 or 3 cabinets or preferably they should be inactivated so as to be handled under BSL-2 precautions.<ref name=":11" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Asogun|first=Danny A.|last2=Adomeh|first2=Donatus I.|last3=Ehimuan|first3=Jacqueline|last4=Odia|first4=Ikponmwonsa|last5=Hass|first5=Meike|last6=Gabriel|first6=Martin|last7=Ölschläger|first7=Stephan|last8=Becker-Ziaja|first8=Beate|last9=Folarin|first9=Onikepe|date=2012-09-27|title=Molecular Diagnostics for Lassa Fever at Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Nigeria: Lessons Learnt from Two Years of Laboratory Operation|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3459880/|journal=PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases|volume=6|issue=9|doi=10.1371/journal.pntd.0001839|issn=1935-2727|pmc=3459880|pmid=23029594}}</ref> In West Africa false-negative results can occur if the probe or antibody pairs do not adequately bind to the target, This can be due to the high diversity of nucleotide and amino acid of the Lassa virus isolates sequenced.<ref name=":11" /> For instance, a widely used RT-PCR assay in West Africa<ref name=":11" /> was modified when when primer-template mismatch lead false negatives results.<ref name=":11" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Currently, two national laboratories in Nigeria are supporting the laboratory confirmation PCR tests.<ref name=":15" /> All the samples are also tested for Ebola, dengue and yellow fever (which have so far tested negative).<ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last=Olalekan|first=Adebimpe Wasiu|date=2016-11-02|title=Pre-epidemic preparedness and the control of Lassa fever in Southern Nigeria|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/rejhs.v4i3.7|journal=Research Journal of Health Sciences|volume=4|issue=3|pages=243|doi=10.4314/rejhs.v4i3.7|issn=2467-8252}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[w:ELISA|'''Enzyme – linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)''']] can be used to detect specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies or viral antigens in acute serum samples from patients with Lassa fever. (It can be detected even in acute phase) |

|||

* [[w:reverse_transcription_polymerase_chain_reaction|'''Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction''']] '''(RT–PCR) assay''' |

|||

| ⚫ | * [[w:Viral_culture| |

||

* [[w:Blood_culture|'''Blood cultures''']] to differentiate other pathogens (e.g. typhoid) and '''blood smear''' to differentiate malaria parasite as the virus can present concomitantly with other diseases |

|||

| ⚫ | * General biochemical tests such as [[w:Complete_blood_count|full blood count]], [[w:Erythrocyte_sedimentation_rate|erythrocyte sedimentation rate]]; [[w:Hematocrit|hematocrit]] volume (to exclude anemia); |

||

==Treatment== |

|||

| ⚫ | The |

||

| ⚫ | {{Main|w:Ribavirin}}Supportive (symptomatic) management includes bed rest; close observation and monitoring; serial laboratory tests; [[w:Analgesic|analgesics]] (e.g. acetaminophen); tepid sponging and [[w:Antipyretic|antipyretic]] drugs to reduce fever; [[w:Antiemetic|antiemetic]] drugs (e.g. metoclopramide and promethazine); prompt fluid and electrolyte replacement; [[w:Diuretic|diuretics]] (e.g. furosemide) for fluid retention; oxygen therapy; blood and/or platelet transfusion; and management of other complications.<ref name=":16">National Guidelines for Lassa fever case management (2018) | Nigeria Center for Disease Control | https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/docs/protocols/92_1547068532.pdf</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In terms of specific management, early initiation of Ribavirin is most effective treatment.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Raabe|first=Vanessa N.|last2=Kann|first2=Gerrit|last3=Ribner|first3=Bruce S.|last4=Morales|first4=Andres|last5=Varkey|first5=Jay B.|last6=Mehta|first6=Aneesh K.|last7=Lyon|first7=G. Marshall|last8=Vanairsdale|first8=Sharon|last9=Faber|first9=Kelly|date=2017-09-01|title=Favipiravir and Ribavirin Treatment of Epidemiologically Linked Cases of Lassa Fever|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5682919/|journal=Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America|volume=65|issue=5|pages=855–859|doi=10.1093/cid/cix406|issn=1058-4838|pmc=5682919|pmid=29017278}}</ref> Intravenous interferon may also be given alongside ribavirin.<ref name=":6" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Currently, two |

||

== |

=== Ribavirin === |

||

| ⚫ | The generic drug [[wikipedia:Ribavirin|ribavirin]] is a broad–spectrum antiviral nucleoside (guanosine).<ref name=":14" /> Its international brand names include Copegus, Ibavyr, Moderiba, Virazole, Virazide, Rebetol, Ribasphere, RibaTab and Riboflax, among many others.<ref name=":14">{{Cite web|url=https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00811|title=Ribavirin|website=www.drugbank.ca|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Supportive (symptomatic) management includes bed rest; close observation and monitoring; serial laboratory tests; [[w:Analgesic|analgesics]] (e.g. acetaminophen); tepid sponging and [[w:Antipyretic|antipyretic]] drugs to reduce fever; [[w:Antiemetic| |

||

==== Medical use ==== |

|||

| ⚫ | In terms of specific management, early |

||

Ribavirin is the primary drug of choice in treating Lassa fever infection.<ref name=":14"/> It has also shown effectiveness in treating other viral infections like hepatitis B.<ref name=":14" /><ref>{{Cite journal|date=2019-06-05|title=Ribavirin|url=https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ribavirin&oldid=900464074|journal=Wikipedia|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

===Pharmacology of ribavirin=== |

|||

| ⚫ | Documented or known hypersensitivity, compromised renal function, or renal failure ([[w:Creatinine|creatinine]] clearance <30 ml/min), pregnancy, [[w:Hemoglobinopathy|hemoglobinopathies]] (e.g. [[w:Thalassemia|Thelassemia]] major, [[w:Sickle_cell_disease|sickle cell]] anemia (with hemoglobin level less than 8g/dl) etc.) are (relative) contraindications to ribavirin.<ref name=":8">{{Cite web|url=https://www.rxlist.com/rebetol-side-effects-drug-center.htm|title=Common Side Effects of Rebetol (Ribavirin) Drug Center|website=RxList|language=en|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The generic drug |

||

==== |

==== Adverse effects ==== |

||

| ⚫ | Although the mechanism of ribavirin remains unclear, ribavirin appears to be a non–specific antiviral agent with most of its efficacy due to incorporation of ribavirin into the viral genome. When cells are exposed to ribavirin, there is reduction in intracellular guanosine triphosphate (a requirement for translation, [[w:Viral_replication#Transcription_/_mRNA_production|transcription]] and [[w:Viral_replication|replication]] in viruses). Therefore ribavirin significantly inhibits viral replication and translation by inhibiting DNA and RNA synthesis.<ref name=":6">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/58604581|title=Antiviral agents, vaccines, and immunotherapies|last=Tyring, Stephen K. (Stephen Keith)|date=2005|publisher=Marcel Dekker|isbn=9780824754082|location=New York|oclc=58604581}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | * Fatal and no-fatal myocardial infarction can occur in persons with ribavirin induced anemia. Cardiac assessment should be done before commencement of therapy. Individuals with known cardiac compromise should have [[w:Electrocardiography|electrocardiography]] monitored during therapy.<ref name=":8" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Documented or known hypersensitivity, compromised renal function, or renal failure ([[w:Creatinine|creatinine]] clearance <30 ml/min), pregnancy, [[w:Hemoglobinopathy|hemoglobinopathies]] (e.g. [[w:Thalassemia|Thelassemia]] major, [[w:Sickle_cell_disease|sickle cell]] anemia (with hemoglobin level less than 8g/dl) etc.) are (relative) contraindications to ribavirin. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* Mild hepatic and renal impairment<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

====Drug interactions==== |

==== Drug interactions ==== |

||

Ribavirin inhibits the [[w:Phosphorylation|phosphorylation]] of zidovudine and ostavudin.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web|url=https://www.rxlist.com/rebetol-drug.htm|title=Rebetol (Ribavirin): Side Effects, Interactions, Warning, Dosage & Uses|website=RxList|language=en|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

Ribavirin inhibits the [[w:Phosphorylation|phosphorylation]] of zidovudine and ostavudin.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web|url=https://www.rxlist.com/rebetol-drug.htm|title=Rebetol (Ribavirin): Side Effects, Interactions, Warning, Dosage & Uses|website=RxList|language=en|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

||

==== |

==== Pharmacodynamics ==== |

||

| ⚫ | Although the mechanism of ribavirin remains unclear, ribavirin appears to be a non–specific antiviral agent with most of its efficacy due to incorporation of ribavirin into the viral genome.<ref name=":6" /> When cells are exposed to ribavirin, there is reduction in intracellular guanosine triphosphate (a requirement for translation, [[w:Viral_replication#Transcription_/_mRNA_production|transcription]] and [[w:Viral_replication|replication]] in viruses).<ref name=":6" /> Therefore ribavirin significantly inhibits viral replication and translation by inhibiting DNA and RNA synthesis.<ref name=":6">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/58604581|title=Antiviral agents, vaccines, and immunotherapies|last=Tyring, Stephen K. (Stephen Keith)|date=2005|publisher=Marcel Dekker|isbn=9780824754082|location=New York|oclc=58604581}}</ref> |

||

Adverse effects include: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | * Fatal and no-fatal |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* Mild hepatic and renal impairment.<ref name=":8">{{Cite web|url=https://www.rxlist.com/rebetol-side-effects-drug-center.htm|title=Common Side Effects of Rebetol (Ribavirin) Drug Center|website=RxList|language=en|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

|||

====Ribavirin in pregnancy==== |

==== Ribavirin in pregnancy ==== |

||

Ribavirin |

Ribavirin can cause birth defects and/or death of exposed fetuses.<ref name=":8" /> Studies done on animal species, reveals that ribavirin had considerable [[w:Teratology|teratogenic]] and/or embryocidal effects.<ref name=":8" /> These adverse effects occurred at even lower than recommended human dose of ribavirin.<ref name=":8" /> |

||

Ribavirin therapy should not be |

Ribavirin therapy should not be commenced in females until serum pregnancy test is negative.<ref name=":7" /> Care should be taken to prevent pregnancy in females with male infected partners (as ribavirin can be excreted via sperm).<ref name=":7" /> To prevent pregnancy the female partners should be instructed to use 2 contraceptive (condoms and any other non barrier method) for 6 months after their partners have been weaned off treatment.<ref name=":7" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://reference.medscape.com/drug/rebetol-ribasphere-ribavirin-342625#6|title=Rebetol, Ribasphere (ribavirin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more|website=reference.medscape.com|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

||

'''Note:''' In pregnancy the goal is to save the mother’s life. As ribavirin therapy cannot be started with pregnancy because of the risks it poses to the mother and fetus, in some cases labor must be induced to save the mother’s life after which ribavirin therapy can begin immediately, especially in third trimesters. |

'''Note:''' In pregnancy the goal is to save the mother’s life.<ref name=":16" /> As ribavirin therapy cannot be started with pregnancy because of the risks it poses to the mother and fetus.<ref name=":16" /> Conservative management can be explored in pregnant women infected with Lassa fever, but in some cases labor must be induced to save the mother’s life after which ribavirin therapy can begin immediately, especially in third trimesters.<ref name=":16" /> |

||

==Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)== |

==Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)== |

||

Individuals who come in contact with infected persons or equipment (i.e. via broken skin, mucous membrane or needle stick injuries) approximately within 2 days of exposure, are given 800 mg of ribavirin daily or 400 mg twice daily for 10 days.<ref name=":17" /> This was the proposal of Vito ''et al.'' in 2010, following their experimental research in [[w:Sierra_Leone|Sierra Leone's]] Lassa ward on only 25 people who were exposed to the virus, all being negative after the prophylaxis.<ref name=":17" /> But there is no substantial evidence to support the effectiveness of immediate initiation of PEP.<ref name=":17">{{Cite web|url=https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/12/pdfs/10-0994.pdf|title=Ribavirin for Lassa Fever Postexposure Prophylaxis|last=|first=|date=|website=wwwnc.cdc.gov|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=2017-04-16}}</ref> |

|||

However the [[w:Centers_for_Disease_Control_and_Prevention|CDC]] recommends placing high-risk exposed individuals under medical surveillance for 21 days and treating presumptively with ribavirin if clinical evidence of viral hemorrhagic fever develops.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hadi|first=Christiane M.|last2=Goba|first2=Augustine|last3=Khan|first3=Sheik Humarr|last4=Bangura|first4=James|last5=Sankoh|first5=Mbalu|last6=Koroma|first6=Saffa|last7=Juana|first7=Baindu|last8=Bah|first8=Alpha|last9=Coulibaly|first9=Mamadou|date=2010-12|title=Ribavirin for Lassa Fever Postexposure Prophylaxis|url=http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/12/10-0994_article.htm|journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases|volume=16|issue=12|pages=2009–2011|doi=10.3201/eid1612.100994|issn=1080-6040}}</ref> |

However the [[w:Centers_for_Disease_Control_and_Prevention|CDC]] recommends placing high-risk exposed individuals under medical surveillance for 21 days and treating presumptively with ribavirin if clinical evidence of viral hemorrhagic fever develops.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hadi|first=Christiane M.|last2=Goba|first2=Augustine|last3=Khan|first3=Sheik Humarr|last4=Bangura|first4=James|last5=Sankoh|first5=Mbalu|last6=Koroma|first6=Saffa|last7=Juana|first7=Baindu|last8=Bah|first8=Alpha|last9=Coulibaly|first9=Mamadou|date=2010-12|title=Ribavirin for Lassa Fever Postexposure Prophylaxis|url=http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/12/10-0994_article.htm|journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases|volume=16|issue=12|pages=2009–2011|doi=10.3201/eid1612.100994|issn=1080-6040}}</ref> |

||

==Prognosis== |

==Prognosis== |

||

About 15 – 20% of hospitalized Lassa fever |

About 15 – 20% of those hospitalized with Lassa fever die from the illness.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/1609/prognosis|title=Lassa fever - prognosis|last=|first=|date=|website=bestpractice.bmj.com|publisher=BMJ|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=2019-06-27}}</ref> The mortality rate of pregnant women infected with Lassa fever is 80%, 87% at second and third trimester respectively and 95% experience fetal deaths. [[w:Mortality_rate|Mortality rate]] during epidemics can be as high as 50%.<ref name=":4" /> |

||

The occurrence of deafness is 25% in persons cured from the disease. half of these persons regain hearing partially after 1 – 3 months.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

==Prevention and control== |

==Prevention and control== |

||

{{main|w:Prevention of viral hemorrhagic fever}} |

{{main|w:Prevention of viral hemorrhagic fever}} |

||

Initiating good “community hygiene” which will prevent rodents from entering homes.<ref name=":4" /> Other steps include storing foodstuffs in rodent–proof containers, good sewage and garbage disposal and keeping rat-predator such as cats.<ref name=":4" /> Rodents are abundant in endemic regions and very hard to completely eliminate, so it is advised that contact should be prevented as much as possible.<ref name=":4" /> While caring for sick persons, caregivers should prevent contact with all bodily fluid. The government and stakeholder should also ensure safe burial process are sustained.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lassa-fever|title=Lassa fever|website=www.who.int|language=en|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> |

|||

Clinical staffs managing persons infected or suspected to have the disease should maintain standard infection prevention and control protocols when attending to these individuals, despite their postulated diagnosis.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.sterlinghealthmcs.com/index.php/blog0/item/894-lassa-fever|title=Lassa Fever|last=|first=|date=|website=www.sterlinghealthmcs.com|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref><ref name=":20">{{Cite journal|last=Ogbu|first=O.|last2=Ajuluchukwu|first2=E.|last3=Uneke|first3=C. J.|date=2007-3|title=Lassa fever in West African sub-region: an overview|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17378212|journal=Journal of Vector Borne Diseases|volume=44|issue=1|pages=1–11|issn=0972-9062|pmid=17378212}}</ref> |

|||

Proper isolation of suspected and confirmed cases of Lassa fever, good quarantine protocols, health education and rigorous contact tracing should be employed by the government and health care agencies. Drugs, equipment and appropriate expertise should also be readily available to control the spread in time.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/262885308|title=The Lassa ward : one man's fight against one of the world's deadliest diseases|last=I.|first=Donaldson, Ross|date=2009|publisher=St. Martin's Press|isbn=0312377002|edition=1st ed|location=New York|oclc=262885308}}</ref> |

Proper isolation of suspected and confirmed cases of Lassa fever, good quarantine protocols, health education and rigorous contact tracing should be employed by the government and health care agencies.<ref name=":18" /> Drugs, equipment and appropriate expertise should also be readily available to control the spread in time.<ref name=":18">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/262885308|title=The Lassa ward : one man's fight against one of the world's deadliest diseases|last=I.|first=Donaldson, Ross|date=2009|publisher=St. Martin's Press|isbn=0312377002|edition=1st ed|location=New York|oclc=262885308}}</ref> |

||

==Additional information== |

==Additional information== |

||

Revision as of 10:33, 29 June 2019

WikiJournal of Medicine

Open access • Publication charge free • Public peer review • Wikipedia-integrated

This article has been through public peer review.

First submitted:

Accepted:

Reviewer comments

PDF: Download

DOI: 10.15347/wjm/2019.002

QID: Q71419342

XML: Download

Share article

![]() Email

|

Email

| ![]() Facebook

|

Facebook

| ![]() Twitter

|

Twitter

| ![]() LinkedIn

|

LinkedIn

| ![]() Mendeley

|

Mendeley

| ![]() ResearchGate

ResearchGate

Suggested citation format:

Abdulmutalab Musa (19 June 2019). "An overview of Lassa fever". WikiJournal of Medicine 6 (1): 2. doi:10.15347/WJM/2019.002.2. Wikidata Q71419342. ISSN 2002-4436.

License: ![]()

![]() This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original author and source are credited.

Roger Watson ![]() (handling editor) contact

(handling editor) contact

Diptanshu Das ![]() contact

contact

Article information

Abstract

Lassa fever was first elucidated in the 1950s, but the virus was not recognized until 1969 when it infected 2 missionary Nurses in Lassa town Borno State, Northeastern Nigeria.[1] Approximately 80% of infected persons are asymptomatic. Rodents of Mastomys genus, often known as the Natal multimammate rat (or mouse) or common African rat are the reservoir of Lassa virus.[1] When the rodents become infected with Lassa virus, they infect humans through their urine and faeces, but remain unharmed.[6] Because of its similarities with other febrile diseases, (e.g. malaria, typhoid, Ebola hemorrhagic fever etc.), early detection is difficult. Thus when persons have persistent fever not responding to normal conventional therapies, they should be screened for other possible causes (especially in endemic regions). When the presence of Lassa fever is established in a community, immediate isolation of infected individuals, screening, standard infection prevention and control practices and meticulous contact tracing can halt outbreaks.[1] Treatment involves supportive measures and early use of the antiviral drug ribavirin.

Pathophysiology

Lassa virus is a single-stranded negative sense RNA virus (Figure 1).[4] The transmission of Lassa virus to humans can occur through direct contact and aerosols generated from the urine or feces of an infected rodent[6]. Natal multimammate rats shed the virus in urine and droppings, direct contact with these excreta, through touching soiled objects, eating contaminated food, or exposure to open cuts or sores, can lead to infection.[6][7] There have been reports of sexual transmission of Lassa fever but it is rare.[8] High serum virus titres, combined with disseminated replication in tissues and absence of neutralizing antibodies (immuno-compromisation), lead to the development of Lassa fever.[4] However, an intact and active immune response is protective against developing symptoms by mounting the early innate immune response in order to prevent further infection and virus growth, which in turn attenuates humoral and cell-mediated immunity.[6][9][10] Due to limited data on Lassa fever, the immune responses against it and its pathogenesis are poorly understood.[6] As such, it is not well understood how viral infection leads to sepsis-like symptoms, cytokine storms or bacterial co-infection.[11][12]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, public domain

There are several pathways involved in the pathogenesis of Lassa fever.[4][13] Similar to the pathogenesis of sepsis, induction of uncontrolled cytokine expression can be triggered by Lassa virus infection.[4] Systemic viral-induced immunosuppression can also be implicated in severe Lassa virus infections.[4]

Two immunoglobulins (IgM and IgG antibody isotypes) are produced in Lassa virus infected person, because both can be present in viremic persons, and possibly only non-neutralizing antibodies are produced early in the infectious process, this makes the antibodies to remain present in a-lot of persons across West Africa, while late antibodies are protective because they neutralize the virus.[4][13] Early antibodies are not neutralizing making them resistant; this is because proteinous surface of the Lassa virus is protected by under-processed glycans form with structurally distinct clusters.[6][14][15]

The main underlying feature of Lassa fever is that the vascular bed is attacked by the virus, with resultant micro-vascular damage and changes in vascular permeability.[4][16] Secondary resultant of capillary leak syndrome and reduced blood volume may include increased cardiac activity, local tissue acidosis, anoxia and reduction in blood circulation, thus leading to the shock syndrome.[16] Generally it is clear that liver damage occurs in almost all cases of Lassa fever in different levels.[4]

Pre–renal acute kidney failure, lactic acidaemia, hyperkalaemia and reduced perfusion and oxygenation of vital tissues follows and progress to fatal outcome.[16][17] The secondary effects of micro-vascular damage include alterations in pulmonary function due to several mechanisms.[17]

Frequency (epidemiology)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, public domain

Estimating the true incidence and mortality of Lassa Fever is extremely difficult due to the non-specific clinical presentation; poor surveillance systems; sizeable human migration, uneasy landscape and lack of standard laboratory confirmation.[19]

Nevertheless, Lassa fever frequently infects people in West Africa (Figure 2) with approximately 80% being asymptomatic.[20] Studies show up to 300,000 – 500,000 cases annually and about 5,000 deaths. Lassa fever is endemic in some parts of West Africa, which includes Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, Guinea and Nigeria.[20]

There have been reports of Lassa fever in neighboring countries; In 2016, two cases were reported in Togo,[21] and 6 confirmed cases in Benin.[22] In the US on 25 May 2015, there was a confirmed case in a US returnee from Liberia.[23] There have been imported cases of Lassa fever in European countries including Sweden,[24] Germany,[25] The Netherlands[26] and the United Kingdom,[27] all of which where imported from West Africa.[28]

Outbreak in Nigeria

In Nigeria, from 1 January to 20 May 2018, 1940 suspected cases have been reported from 21 states.[29] Of these, 431 were confirmed positive, 10 are probable, 1495 negative.[29][1] A total of 6489 contacts have been identified in 20 states since January 2019 to March 2019, a total of 2034 suspected cases have been reported from 21 states.[29] Of these, 526 were confirmed positive, 15 probable and 1693 negative (not a case).[29] out of these, 17 health care workers have been affected in six states with four deaths (case fatality rate= 29%).[29]

Presentation

Lassa fever has an incubation period of 6 – 21 days.[1] The onset of lassa fever is usually asymptomatic and when symptomatic it is usually subtle, starting with fever and malaise. When it progresses, it presents with sore throat, headache, achy muscle, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, diarrhea, cough, and abdominal pain.[1][30] In critical cases systemic involvement occurs with the following:

- Respiratory: pleural effusion, epistaxis, rales, rhonchi, stridor, cough, wheezing, pharyngitis, and dyspnoea[17][31]

- Gastrointestinal: hematemesis, melena, gingival bleeding, dysphagia, hepatitis, and hepatic tenderness[17][31]

- Renal: hematuria, dysuria[17]

- Cardiovascular: pericarditis, hypotension, and tachycardia[17][31]

- Nervous: encephalitis, cloudy sensorium, seizures, disorientation, and coma, unilateral or bilateral hearing deficit[17][31]

- Vascular: petechial and ecchymotic cuteneous lesions, facial and cervical edema[17][31]

Temporary hair loss and gait interference may occur during recovery.[1][32]

Lassa fever is usually fatal within 14 days of inception[1][33]

Causes and transmission

Lassa virus is zoonotic,[1][34] as it spreads specifically from Natal multimammate mice (Mastomys natalensis).[1][34] It is the most prevalent mouse in equatorial Africa, omnipresent in households and consumed as food in some areas.[35] Infection occurs by exposure to rat excreta directly or indirectly via contaminated food stuffs.[34] Infection can also occur by inhalation of tiny particles (aerosols) of infected materials, airborne transmission is rare as there is no evidence to support that.[1] It is possible to acquire infection through broken skin or mucous membranes that is directly exposed to infectious materials, and through rat bites.[1][34] In addition, the virus can also be contracted via contaminated hospital equipment, such as re–used needles and improper sterilization.[1] The presence of Lassa virus in the semen indicates high risk of sexual transmission but viral load is not enough to cause infection.[36]

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of Lassa fever disease is usually difficult, this is as a result of it vague symptoms.[1] Lassa fever is hard to differentiate from other febrile diseases e.g. malaria, typhoid, influenza, relapsing fever, leptospirosis and other hemorrhagic fevers e.g. yellow fever, dengue, Marburg and Ebola.[1][37]

The following laboratory tests can be conducted:[1]

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) can be used to detect specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies or viral antigens in acute serum samples from persons with Lassa fever (it can be detected even in acute phase).[38]

- Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) assay can be used in early stage to detect the virus using inactivated virus. it is very helpful in areas where BSL4 laboratories cannot be found especially in west Africa.[39]

- Virus cultivation and identification technique (virus isolation by cell culture). However, this requires 3 – 10 days or longer for definitive identification.[40][41]

- Blood cultures to differentiate other pathogens (e.g. typhoid)[42] and blood smear to differentiate malaria parasite[43] as the virus can present concomitantly with other diseases.[33]

- General biochemical tests such as full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; hematocrit volume (to exclude anemia); white blood cell count (to exclude lymphopenia); platelet count (to exclude thrombocytopenia), coagulation studies (to exclude coagulopathies) and liver and kidney function tests (serum liver enzymes have been found to be positive clinical markers).[44]

The WHO guidelines for the collection, storage, and handling of Ebola virus specimens testing should be adhered to when testing for Lassa virus.[45] Thorough adherence to biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) precautions is pertinent when handling suspected specimens.[45] However, BSL-4 laboratories are limited worldwide, when not available, samples should be handled in biosafety level 2 or 3 cabinets or preferably they should be inactivated so as to be handled under BSL-2 precautions.[45][46] In West Africa false-negative results can occur if the probe or antibody pairs do not adequately bind to the target, This can be due to the high diversity of nucleotide and amino acid of the Lassa virus isolates sequenced.[45] For instance, a widely used RT-PCR assay in West Africa[45] was modified when when primer-template mismatch lead false negatives results.[45]

Currently, two national laboratories in Nigeria are supporting the laboratory confirmation PCR tests.[47] All the samples are also tested for Ebola, dengue and yellow fever (which have so far tested negative).[47]

Treatment

Supportive (symptomatic) management includes bed rest; close observation and monitoring; serial laboratory tests; analgesics (e.g. acetaminophen); tepid sponging and antipyretic drugs to reduce fever; antiemetic drugs (e.g. metoclopramide and promethazine); prompt fluid and electrolyte replacement; diuretics (e.g. furosemide) for fluid retention; oxygen therapy; blood and/or platelet transfusion; and management of other complications.[48]

In terms of specific management, early initiation of Ribavirin is most effective treatment.[49] Intravenous interferon may also be given alongside ribavirin.[50]

Ribavirin

The generic drug ribavirin is a broad–spectrum antiviral nucleoside (guanosine).[51] Its international brand names include Copegus, Ibavyr, Moderiba, Virazole, Virazide, Rebetol, Ribasphere, RibaTab and Riboflax, among many others.[51]

Medical use

Ribavirin is the primary drug of choice in treating Lassa fever infection.[51] It has also shown effectiveness in treating other viral infections like hepatitis B.[51][52]

Contraindications

Documented or known hypersensitivity, compromised renal function, or renal failure (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min), pregnancy, hemoglobinopathies (e.g. Thelassemia major, sickle cell anemia (with hemoglobin level less than 8g/dl) etc.) are (relative) contraindications to ribavirin.[53]

Adverse effects

- Hemolytic anemia may occur within 1 – 2 weeks of initiating therapy. It is recommended that pack cell volume be obtained before treatment is initiated and re-obtained at week 2 and week 4 of therapy or as clinically indicated.[53]

- Fatal and no-fatal myocardial infarction can occur in persons with ribavirin induced anemia. Cardiac assessment should be done before commencement of therapy. Individuals with known cardiac compromise should have electrocardiography monitored during therapy.[53]

- Hypersensitivity, e.g. uticaria, angioedema, bronchoconstriction and anaphylaxis[53]

- Bone marrow suppression (pancytopenia)[53]

- Unusual tiredness and weakness[53]

- Insomnia, depression, irritability and suicidal behavior have been reported with oral administration[53]

- Ocular problems[53]

- Mild hepatic and renal impairment[53]

Drug interactions

Ribavirin inhibits the phosphorylation of zidovudine and ostavudin.[54]

Pharmacodynamics

Although the mechanism of ribavirin remains unclear, ribavirin appears to be a non–specific antiviral agent with most of its efficacy due to incorporation of ribavirin into the viral genome.[50] When cells are exposed to ribavirin, there is reduction in intracellular guanosine triphosphate (a requirement for translation, transcription and replication in viruses).[50] Therefore ribavirin significantly inhibits viral replication and translation by inhibiting DNA and RNA synthesis.[50]

Ribavirin in pregnancy

Ribavirin can cause birth defects and/or death of exposed fetuses.[53] Studies done on animal species, reveals that ribavirin had considerable teratogenic and/or embryocidal effects.[53] These adverse effects occurred at even lower than recommended human dose of ribavirin.[53]

Ribavirin therapy should not be commenced in females until serum pregnancy test is negative.[54] Care should be taken to prevent pregnancy in females with male infected partners (as ribavirin can be excreted via sperm).[54] To prevent pregnancy the female partners should be instructed to use 2 contraceptive (condoms and any other non barrier method) for 6 months after their partners have been weaned off treatment.[54][55]

Note: In pregnancy the goal is to save the mother’s life.[48] As ribavirin therapy cannot be started with pregnancy because of the risks it poses to the mother and fetus.[48] Conservative management can be explored in pregnant women infected with Lassa fever, but in some cases labor must be induced to save the mother’s life after which ribavirin therapy can begin immediately, especially in third trimesters.[48]

Post Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

Individuals who come in contact with infected persons or equipment (i.e. via broken skin, mucous membrane or needle stick injuries) approximately within 2 days of exposure, are given 800 mg of ribavirin daily or 400 mg twice daily for 10 days.[56] This was the proposal of Vito et al. in 2010, following their experimental research in Sierra Leone's Lassa ward on only 25 people who were exposed to the virus, all being negative after the prophylaxis.[56] But there is no substantial evidence to support the effectiveness of immediate initiation of PEP.[56]

However the CDC recommends placing high-risk exposed individuals under medical surveillance for 21 days and treating presumptively with ribavirin if clinical evidence of viral hemorrhagic fever develops.[57]

Prognosis

About 15 – 20% of those hospitalized with Lassa fever die from the illness.[58] The mortality rate of pregnant women infected with Lassa fever is 80%, 87% at second and third trimester respectively and 95% experience fetal deaths. Mortality rate during epidemics can be as high as 50%.[1]

The occurrence of deafness is 25% in persons cured from the disease. half of these persons regain hearing partially after 1 – 3 months.[1]

Prevention and control

Initiating good “community hygiene” which will prevent rodents from entering homes.[1] Other steps include storing foodstuffs in rodent–proof containers, good sewage and garbage disposal and keeping rat-predator such as cats.[1] Rodents are abundant in endemic regions and very hard to completely eliminate, so it is advised that contact should be prevented as much as possible.[1] While caring for sick persons, caregivers should prevent contact with all bodily fluid. The government and stakeholder should also ensure safe burial process are sustained.[1]

Clinical staffs managing persons infected or suspected to have the disease should maintain standard infection prevention and control protocols when attending to these individuals, despite their postulated diagnosis.[59][31]

Proper isolation of suspected and confirmed cases of Lassa fever, good quarantine protocols, health education and rigorous contact tracing should be employed by the government and health care agencies.[60] Drugs, equipment and appropriate expertise should also be readily available to control the spread in time.[60]

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interest.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 "Lassa fever". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ↑ Oti, Victor B. (2018-11-05). "A Reemerging Lassa Virus: Aspects of Its Structure, Replication, Pathogenicity and Diagnosis". Current Topics in Tropical Emerging Diseases and Travel Medicine. doi:10.5772/intechopen.79072. https://www.intechopen.com/books/current-topics-in-tropical-emerging-diseases-and-travel-medicine/a-reemerging-lassa-virus-aspects-of-its-structure-replication-pathogenicity-and-diagnosis.

- ↑ Monath, T. P.; Casals, J. (1975). "Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 52 (4-6): 707–715. ISSN 0042-9686. PMID 1085225. PMC PMC2366641. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Yun, Nadezhda E.; Walker, David H. (2012-10-09). "Pathogenesis of Lassa Fever". Viruses 4 (10): 2031–2048. doi:10.3390/v4102031. ISSN 1999-4915. PMID 23202452. PMC PMC3497040. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3497040/.

- ↑ Monath, T. P.; Casals, J. (1975). "Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 52 (4-6): 707–715. ISSN 0042-9686. PMID 1085225. PMC PMC2366641. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Hallam, Hoai J.; Hallam, Steven; Rodriguez, Sergio E.; Barrett, Alan D. T.; Beasley, David W. C.; Chua, Arlene; Ksiazek, Thomas G.; Milligan, Gregg N. et al. (2018-03-20). "Baseline mapping of Lassa fever virology, epidemiology and vaccine research and development". NPJ Vaccines 3. doi:10.1038/s41541-018-0049-5. ISSN 2059-0105. PMID 29581897. PMC 5861057. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5861057/.

- ↑ "Transmission of Lassa Fever". www.cdc.gov. 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ↑ Oshin, Babafemi A. (2019-04-09). Rat eating, sexual transmission and the burden of Lassa fever disease (in en). https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/rat-eating-sexual-transmission-and-burden-lassa-fever-disease.

- ↑ Zapata, Juan Carlos; Medina-Moreno, Sandra; Guzmán-Cardozo, Camila; Salvato, Maria S. (2018-10-28). "Improving the Breadth of the Host’s Immune Response to Lassa Virus". Pathogens 7 (4). doi:10.3390/pathogens7040084. ISSN 2076-0817. PMID 30373278. PMC 6313495. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6313495/.

- ↑ Brosh-Nissimov, Tal (2016-04-30). "Lassa fever: another threat from West Africa". Disaster and Military Medicine 2. doi:10.1186/s40696-016-0018-3. ISSN 2054-314X. PMID 28265442. PMC 5330145. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5330145/.

- ↑ Lin, Gu-Lung; McGinley, Joseph P.; Drysdale, Simon B.; Pollard, Andrew J. (2018-09-27). "Epidemiology and Immune Pathogenesis of Viral Sepsis". Frontiers in Immunology 9. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02147. ISSN 1664-3224. PMID 30319615. PMC 6170629. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6170629/.

- ↑ USA US9193705B2, Template:Cite patent/authors, "Small molecule inhibitors of ebola and lassa fever viruses and methods of use"

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Lassa". Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Consortium. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ↑ Crispin, Max; Bowden, Thomas A.; Strecker, Thomas; Huiskonen, Juha T.; Moser, Felipe; Li, Sai; Seabright, Gemma E.; Allen, Joel D. et al. (2018-07-10). "Structure of the Lassa virus glycan shield provides a model for immunological resistance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (28): 7320–7325. doi:10.1073/pnas.1803990115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 29941589. https://www.pnas.org/content/115/28/7320.

- ↑ Robinson, James E.; Hastie, Kathryn M.; Cross, Robert W.; Yenni, Rachael E.; Elliott, Deborah H.; Rouelle, Julie A.; Kannadka, Chandrika B.; Smira, Ashley A. et al. (2016-05-10). "Most neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies target novel epitopes requiring both Lassa virus glycoprotein subunits". Nature Communications 7. doi:10.1038/ncomms11544. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 27161536. PMC 4866400. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4866400/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Brisse, Morgan E.; Ly, Hinh (2019-03-13). "Hemorrhagic Fever-Causing Arenaviruses: Lethal Pathogens and Potent Immune Suppressors". Frontiers in Immunology 10. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00372. ISSN 1664-3224. PMID 30918506. PMC 6424867. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6424867/.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 Monath, T. P.; Casals, J. (1975). "Diagnosis of Lassa fever and the isolation and management of patients". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 52 (4-6): 707–715. ISSN 0042-9686. PMID 1085225. PMC PMC2366641. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2366641/.

- ↑ "Outbreak Distribution Map of Lassa Fever". www.cdc.gov. CDC. 2019-03-04. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ↑ Grant, Donald S.; Khan, Humarr; Schieffelin, John; Bausch, Daniel G. (2014). Emerging Infectious Diseases (in en). Elsevier. pp. 37–59. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-416975-3.00004-2. ISBN 9780124169753. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780124169753000042.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Behrens, Ron; Houlihan, Catherine (2017-07-12). "Lassa fever". BMJ 358: j2986. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2986. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 28701331. https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j2986.

- ↑ "Lassa Fever – Togo". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "Lassa Fever – Benin". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "Lassa Fever – United States of America". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "Lassa fever – Sweden". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "Lassa Fever – Germany". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "2000 - Imported case of Lassa fever in The Netherlands - Update". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "Imported case of Lassa fever in United Kingdom". WHO. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ↑ "WHO | Lassa fever". WHO. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 "Nigeria Centre for Disease Control". www.ncdc.gov.ng. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ↑ "Lassa fever - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment". bestpractice.bmj.com. BMJ. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Ogbu, O.; Ajuluchukwu, E.; Uneke, C. J. (2007-3). "Lassa fever in West African sub-region: an overview". Journal of Vector Borne Diseases 44 (1): 1–11. ISSN 0972-9062. PMID 17378212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17378212.

- ↑ Behrens, Ron; Houlihan, Catherine (2017-07-12). "Lassa fever". BMJ 358: j2986. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2986. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 28701331. https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j2986.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Greenky, David; Knust, Barbara; Dziuban, Eric J. (2018-05-01). "What Pediatricians Should Know About Lassa Virus". JAMA pediatrics 172 (5): 407–408. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5223. ISSN 2168-6203. PMID 29507948. PMC PMC5970952. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5970952/.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Kafetzopoulou, L. E.; Pullan, S. T.; Lemey, P.; Suchard, M. A.; Ehichioya, D. U.; Pahlmann, M.; Thielebein, A.; Hinzmann, J. et al. (2019-01-04). "Metagenomic sequencing at the epicenter of the Nigeria 2018 Lassa fever outbreak". Science 363 (6422): 74–77. doi:10.1126/science.aau9343. ISSN 0036-8075. http://www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aau9343.

- ↑ Hussainia, Nafiu; Abdulhamid, Abdurrahman (2018-01-01). "Effects of quarantine on transmission dynamics of Lassa fever". Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 11 (1): 397–407–407. ISSN 2006-6996. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/bajopas/article/view/183493.

- ↑ Oshin, Babafemi A. (2019-04-27). Rat eating, sexual transmission and the burden of Lassa fever disease (in en). https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/rat-eating-sexual-transmission-and-burden-lassa-fever-disease.

- ↑ "Lassa fever". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- ↑ Bausch, D. G. Rollin, P. E. Demby, A. H. Coulibaly, M. Kanu, J. Conteh, A. S. Wagoner, K. D. McMullan, L. K. Bowen, M. D. Peters, C. J. Ksiazek, T. G.. Diagnosis and Clinical Virology of Lassa Fever as Evaluated by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, Indirect Fluorescent-Antibody Test, and Virus Isolation. American Society for Microbiology. OCLC 679252357. http://worldcat.org/oclc/679252357.

- ↑ Koehler, Jeffrey; Raabe, Vanessa (2017-06-01). "Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 55 (6): 1629–1637. doi:10.1128/JCM.00170-17. ISSN 0095-1137. PMID 28404674. https://jcm.asm.org/content/55/6/1629.

- ↑ Raabe, Vanessa; Koehler, Jeffrey (2017-6). Kraft, Colleen Suzanne. ed. "Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 55 (6): 1629–1637. doi:10.1128/JCM.00170-17. ISSN 0095-1137. PMID 28404674. PMC PMC5442519. http://jcm.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/JCM.00170-17.

- ↑ Panning, Marcus; Emmerich, Petra; Ölschläger, Stephan; Bojenko, Sergiusz; Koivogui, Lamine; Marx, Arthur; Lugala, Peter Clement; Günther, Stephan et al. (2010-6). "Laboratory Diagnosis of Lassa Fever, Liberia". Emerging Infectious Diseases 16 (6): 1041–1043. doi:10.3201/eid1606.100040. ISSN 1080-6040. PMID 20507774. PMC PMC3086251. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/6/10-0040_article.htm.

- ↑ Kumar, Praveen; Kumar, Ruchika (2017-3). "Enteric Fever". The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 84 (3): 227–230. doi:10.1007/s12098-016-2246-4. ISSN 0019-5456. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12098-016-2246-4.

- ↑ Kattenberg, Johanna H; Ochodo, Eleanor A; Boer, Kimberly R; Schallig, Henk DFH; Mens, Petra F; Leeflang, Mariska MG (2011-12). "Systematic review and meta-analysis: rapid diagnostic tests versus placental histology, microscopy and PCR for malaria in pregnant women". Malaria Journal 10 (1). doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-321. ISSN 1475-2875. https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-10-321.

- ↑ Salvato, Maria S.; Lukashevich, Igor S.; Medina-Moreno, Sandra; Zapata, Juan Carlos (2018). "Diagnostics for Lassa Fever: Detecting Host Antibody Responses". Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1604: 79–88. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6981-4_5. ISSN 1940-6029. PMID 28986826. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28986826.