Motivation and emotion/Textbook/Motivation/Sexual motivation

Introduction

[edit | edit source]This chapter introduces psychological understandings of sexual motivation. After reading this chapter you will have an understanding of some of the most influential studies in human sexual behavior, the evolution of human sexual behavior, the physiology, gender differences, the role of pheromones, the psychological motives, sociocultural influences and finally research issues in the field of sexual motivation.

To generate new life we need to have sex! However, procreation is not the only motive for people to engage in sexual activities. Sexual motivation is a multidimensional, hierarchical concept that has been equated to that of the motivation of hunger and thirst, primarily due to the similar physiological responses involved. However, unlike hunger and thirst, we will not die if we do not have sex. So why is it so motivating? There is not one factor, motive or thought that can explain sexual motivation, instead it is a subjective motive, specific to an individual. Sexual Motivation is the subjective drive or force that generates our level or sexual interest at any given time. It compels us to seek out through direct sexual activity with another individual or self gratification, drives our sexual fantasies, and regulates our sexual arousal (Pfaus, 1999). Other terms used for sexual motivation include sex drive, sexual appetite, desire or the Freudian term libido (Regan, 1999). Sex drive is usually measured and understood in terms of frequency and intensity of desire.

Kinsey's Landmark Study of Human Sexual Behavior

[edit | edit source]

Alfred Kinsey and colleagues (1953) conducted the most influential study of human sexual behaviour in the 1940’s and 1950’s. Kinsey, a zoologist, wanted to create a taxonomy of sexual behavior, usually constructed in biology. Over a period of nine years Kinsey and colleagues interviewed roughly 12,000 American males and females, to determine sexual fact, void of social or moral interpretations. The results caused major controversy in the conservative time period, as many of the topics in the research were taboo, such as masturbation, pre-marital relations and homosexuality. The Kinsey studies identified the diversity of human sexual behaviour. Kinsey’s approach to collecting data was scrutinised by many, as the method used to collect information were from face to face interviews, using rapid fire questioning. His strategy was to gain a good rapport with the interviewee in hope that they would expose their sexual activities. Kinsey and his colleagues integrated themselves into the communities of people to gain their trust and respect in return for their honesty in responding about their sexual history. This strategy was successful and thus two books, known as the Kinsey Reports, on sexual behaviour were published, one for males (Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin & Gebhard, 1953) and one for females (Kinsey, Pomeory & Martin, 1984). The Kinsey Reports provided a never before researched view of what was actually happening behind closed doors. However the sample was not representative of the general population as it consisted predominately of white, middle class individuals who lived in major cities.

Evolutionary Perspective

[edit | edit source]

There are some notable evolutionary differences between males and females that can assist in understanding gender differences in sexual motivation. Throughout history both genders were faced with problems which they have evolved and adapted to overcome. One such problem is pregnancy because females are required to invest a great deal of time and energy. In comparison, men are only required to contribute a minimal investment of sperm (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). It takes nine months of gestation and many more devoted to the subsequent lactation stage. This poses a threatening problem to females as they must find and secure a reliable and replenishable supply of resources which will take them through the term of pregnancy. Women who were not successful at overcoming this problem did not survive (Buss, 1995). Secondly women were faced with not only the problem of finding a man with resources but finding one who is willing to commit to the women and protect her children.

However, even though women were faced with hefty burdens to reproduce, men were also faced with several problems. Firstly, men had the problem of finding women who were fertile and could bare children. As women's fertility declines with age, men are more likely to seek out mates who signal youth and health as these are the women who will probably be most fertile (Buss & Schmitt). Secondly, men could never be 100% sure that the baby a woman was carrying is their own, whereas women are always 100% certain that the pregnancy is their own. Thus they could be faced with investing resources with offspring who are not genetically theirs. Evolutionary psychologists believe this is the reason for sexual jealousy, and also the strong sexual motivation in men, is to guard their mate from paternity uncertainty known as cuckoldry (Buss & Schmitt; Klusmann, 2006).

Theory of Sexual Motivation

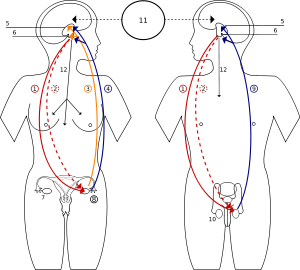

[edit | edit source]Sexual motivation is a multidimensional construct. There are many component processes which interact to collectively generate human sexual motivation (Toates, 2009). One modern theory of sexual motivation and subsequent behaviour is that it is controlled by a combination of external stimuli and internal cognitive events (Toates). Visual processing plays a major role in the activation of certain brain areas and associated sexual arousal. When males were presented with sexually arousing videos areas in the insula and sub insular region of the brain were activated. It is hypothesised that these areas are related to the transfer of visual information to imagined stimulation (Arnow et al., 2002). Simplistically, external stimuli act as an incentive and eventually become conditioned. Conditioned stimuli from external visual cues and internal, such as in the imagination then become a trigger to sexual motivation. These triggers set off physiological arousal, which works on a feedback loop system. The brain sends off impulses through the central nervous system, via the hypothalamus, to the genitals which then feeds back and determines future behaviour (Stellar, 1994). Thus sexual motivation is based on a combination of many aspects.

Physiology of Sexual Motivation

[edit | edit source]

Brain and Hormones

[edit | edit source]The brain can be considered the main sex organ in humans. The brain and other regions in the body are responsible for the release of hormones which assist in altering sexual arousal. However, hormones are not primarily responsible for sexual arousal, instead they assist in how the brain organises and responds to stimuli (Kalat, 2009). Testosterone as been positively associated with frequency of male and female sexual thoughts or fantasy. Testosterone is synthesised in the testes in males and the adrenal cortex in males and females. Low testosterone levels have been associated with a low sex drive in both males and females. It is not certain if predominantly female hormones, progesterone or estrogen have any effect on sexual desire (Regan, 1999).

Human Sexual Response Cycle

[edit | edit source]Masters and Johnson Four Phase Model

[edit | edit source]The Human Sexual Response Cycle is the physiological cycle during typical sexual stimulation. These phases are the physical reactions that result from genital response and include the excitement phase, plateau phase, orgasmic phase and finally the resolution phase (Masters & Johnson, 1966).

|

Four Phases

|

The excitement phase is the intensified feeling of sexual tension and involves the initial influx of blood to the genital areas, which causes the man's penis to partially erect. Many oregenous zones of the woman’s body becomes enlarged or swelled, including the clitoris, vagina, breasts and nipples and opening of the labia minora (inner lips). The vagina begins to secret lubricant.

In the plateau phase the penis becomes fully engorged and secrets seminal fluid. In females, vaginal lubricant increases, the clitoris retracts and orgasm feels as though it is approaching.

The stimuli in combination with drive must be effective to reach the orgasm phase. If the drive or stimuli is withdrawn or inadequate the individual may not reach the orgasm phase and drop into resolution phase. The orgasmic phase is only a few seconds in duration. During orgasm Masters and Johnson (1966) observed intense rhythmic contractions all of over the body of both males and females.

During the resolution phase the body returns back to its unaroused state. During this phase the male enters the refractory period, which can last from a few minutes to a day, during which he is unable to have another orgasm (Myers, 2004).

When developing this model Masters and Johnson observed various couples partaking in sexual intercourse, they noted that the phases varied greatly from one individual to the other. The observed variations were primarily duration and intensity of phases. Females, particularly, consisted of a greater variation of the cycle thus three variations of the sexual response cycle were created.

Kaplan's Three Phase Model

[edit | edit source]|

Three Phases

|

Not satisfied that the Sexual Response Cycle could explain many sexual dysfunctions, Kaplan (1979) proposed a three phase model of human sexual functioning not unrelated to the phases described by Masters and Johnson (1966). Kaplan's three phases include the desire phase, excitement phase and orgasmic phase. The main difference is the desire phase, which encompasses activation of the brain system, is responsible for sexual desire such as the limbic system, receptor cells and circuits, and secondly the physiological mechanisms such as electrical and chemical events. These events produce the drive or sexual appetite which can explain sexual dysfunction (Kaplan).

Gender Differences in Sexual Behaviour

[edit | edit source]What are the gender differences in sexual motivation?

[edit | edit source]

As most people would agree, males have a stronger sex drive in comparison to women. This is greatly due to the higher level of testosterone that males produce (Baumeister, Catanese & Vohs, 2001). Empirical evidence supports this notion; in fact there are no studies with samples of women who have a stronger sex drive then men (Baumeister, Catanese & Vohs, 2001; Sprague & Quadagno,1989). Sex drive is measured across a number of domains including frequency of spontaneous sexual arousal, sexual fantasy, and masturbation. It has been found across many studies that men think about sex more often, report more frequent arousal and have more frequent and variable fantasises, thus supporting the premise that men have a stronger sex drive. Furthermore, men report wanting more sex when they are single, in a relationship and overall desire more sexual partners in their lifespan.

Another indicator of higher sexual drive is the willingness to forgo sex. If a woman looses her partner she will usually discontinue sex for long periods of time or until another partner comes along. Men, comparatively, tend to seek out another partner quite quickly or increase masturbation (Baumeister et al., 2001). However, there are great individual differences in sex drive. A study conducted by Wentland, Herold, Desmarais & Milhausen (2009) on sexual motivation in women identified two types of women, those who are highly sexual and those who are less sexual. There are distinct differences between less and highly sexual women. Similar to men, highly sexual women scored higher on sex drive, a more positive attitude to promiscuity, sexual fantasies and thought, more positive attitude to sexually explicit materials (SEM) on television/DVDs and internet and masturbatory attitudes.

Masturbation

[edit | edit source]

Masturbation can be defined as self gratification of sexual desire. Masturbation has been identified as good indicator of sexual motivation or drive. Studies report that males masturbate far more often than females. Women are more likely than men to report never masturbating at all and those who do masturbate do it much less frequently (Baumeister et al., 2001). Problems with assessing masturbation as a factor of sexual motivation is that society disapproves of it in both genders (Baumeister et al.).

Relationships

[edit | edit source]Does sexual motivation change in relationships? Research on sexual activity in relationships have indicated a negative correlation between relationship length and sexual motivation (Klusmann, 2002). However, regardless of how long a couple have been together, men’s sexual motivation remains constant over the course of a long-term relationship. In comparison, when women first engage in a relationship their sexual motivation matches that of males and then steadily declines through time (Klusmann, 2006). However, Klusmann found an exception to the rule of female sexual motivation. Firstly, female sexual motivation did not decline when the female was not living with her partner or secondly her partner's educational level exceeds her own. Research indicates that sexual satisfaction declines in both women and men in relationships which could be attributed to the decline in desire of women (Klusmann, 2002). However, a study by DeLamater and Sill (2005) found that men and women well into their 70's still experience sexual desire but are influenced by biopsychosocial aspects, particularly the decline in health and/or the use of medications.

Promiscuity

[edit | edit source]

Empirical evidence also supports the notion that men prefer sexual variety in comparison to women. A study assessing four different samples all resulted in men having a higher preference for many partners. Men want on average 14 partners, comparatively women reported only wanting two over their lifetime. One explanation for these findings is not biological but instead cultural in the form of gender socialisation. Men grow up under the perception, from observing others, that masculinity is defined as a preference towards sexual variety and short term mating (Schmitt, Shackelford, Duntley, Tooke & Buss, 2001). These findings were also replicated in a homosexual sample. Homosexual males had a higher number of sexual partners and were more sexually compulsive, whereas homosexual females were more likely to be in a committed monogamous relationship (Missildine, Feldstein, Punzalan & Parsons, 2005). Furthermore, men will engage in sex after knowing someone in as short a time as a week, whereas females are more likely to engage in sex after knowing someone for six months (Buss & Schmitt, 1993).

It can be safe to say that men indeed do have a stronger sex drive than women, though this does not necessarily imply that they enjoy or get more pleasure from sex than women do.

Pheromones

[edit | edit source]

Pheromones play a large role in interactions between genes, nerve cells, hormones and neural pathways during development; they also influence learning, memory and behaviour (Kohl & Francoeur, 1995). Thus, odours and smell probably play a much greater role than we think in human social interactions, sexual attraction, sexual arousal, mating, boding and parenting.

What are Pheromones?

[edit | edit source]Pheromones are subliminal odours. Odours that cannot be smelt, but instead are chemical messages which convey information between two or more individuals of the same species. They operate at a level below conscious perception (Kohl & Francoeur). The theory of human pheromones is based on the premise that we are not dissimilar to the biological structures and physiological responses that we share with other animals. The majority of mammals contain a structure called the vomeronasal organ (VNO). This organ is responsible for detecting pheromones via receptors, which relay information to the brain and trigger hormone changes, readying an animal for sexual activity. Humans do not have a VNO so scientists concluded that humans are unresponsive to pheromones (Miller, 2006). However, groundbreaking research by McClintock, (1971, as cited in Schank, 2006) suggested that synchronising of the female menstrual cycle was caused by pheromones. Therefore it could be assumed that the sexual behaviour of animals that is influenced by pheromones could be similar to our own (Kohl & Francoeur).

Sexual Motivation and Pheromones

[edit | edit source]There has been no specific behaviour that has been directly linked to pheromones. It is proposed that the scent of pheromones is released through all areas of the body via skin cell secretions and gaseous glandular secretions in the skin, scalp, feet, mouth, breast, armpits and genital area. Thus the exchange of saliva through kissing may be one common way in which humans exchange their sex pheromones. Furthermore motivation towards oral genital sex may be a drive to experience the pheromones that are being secreted in behind the ridge of the penile glands, in males, and the vaginal pheromones, which increase with the rise of estrogen levels associated with fertility in females (Schank, 2006). However, as romantic as the notion that sexual motivation is driven by pheromones is, so far it is speculative.

Further investigation into the research of menstrual cycles and pheromones found promising results, however, Schank (2006) points out that all eight studies of human pheromones and menstrual cycle are methodologically flawed. This is problematic in the study of human pheromones as this was currently a predominant procedure for testing their existence (Schank). Thus, there is yet to be repeated comprehensive findings to support the role of pheromones in sexual motivation.

Psychology of Sexual Motivation

[edit | edit source]|

Fact

Did you know that half of |

There is great diversity of sexual motivation between individuals. An example of the diversity was discovered in a study by Meston and Buss (2007). Meston and Buss conducted a thorough investigation to determine the psychological motives as to why humans engage in sexual intercourse. Their initial data collection had 237 distinct reasons as to why people have sex. This was analysed down to four factors, physical reasons, goal attainment reasons, emotional reasons and insecurity reasons. Each reason included sub reasons as listed in Table 1w. The core of human sexual motivation was encapsulated by the most frequently rated reasons for why people have sex which included attraction, pleasure, affection, love, romance, emotional closeness, arousal, the desire to please, adventure, excitement, experience, connection, celebration, curiosity and opportunity.

Table 1

Factors and Sub-factors of Why Humans Engage in Sexual Intercourse

| Factor | Sub-factor |

|---|---|

| Physical | Stress Reduction |

| Pleasure | |

| Physical Desirability | |

| Experience Seeking | |

| Goal Attainment | Resources |

| Social Status | |

| Revenge | |

| Utilitarian | |

| Insecurity | Self Esteem Boost |

| Duty/Pressure | |

| Mate Guarding | |

| Emotional | Love and Commitment |

| Expression |

Note. Adapted from "Why Humans Have Sex,'" by C. M. Meston and D. M. Buss, 2007, Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(4), 477-507.

Meston and Buss' (2007) study provided a detailed examination of the gender differences of engaging in sexual intercourse. Men endorsed reasons centred on the physical appearance and physical desirability such as “the person had a desirable body” or “the person's physical appearance turned me on.” This supports the hypothesis that men are more sexually aroused by visual sexual cues then are women. Men also endorsed opportunistic motives such as “the opportunity presented itself” or “the person was available”. Unsurprisingly, women exceeded men in emotional motivations for sex. Love and commitment and expression were the only two sub-factors where there was not a significant gender difference, thus suggesting that both men and women desire emotional intimacy when engaging in sex (Meston & Buss).

Sprague and Quadagno (1989) found similar results to this in their research of gender differences in sexual motivation. Women typically are motivated to engage in sexual intercourse to express love and men are typically motivated by physical factors. However, this study showed that as women age their motives shift from emotional reasons to physical reasons. This could explain why older women, known as cougars, pursue much younger men.

Sociocultural influences

[edit | edit source]|

Want to know your Sex IQ? Click here. |

Since the sexual revolution in the 1960’s and 1970’s there has been a major shift in how women approach sex. Baumeister (2004) suggests that aspects on the environment such as cultural events, historical circumstances, socialisation, peer pressures and influences heavily affect female sexuality. This influence has been termed “erotic plasticity” which is the extent to which sex drive can be shaped by social, cultural and situational factors. Those who have a high plasticity can easily adapt to such factors alternatively those with a low plasticity are more likely to have a stronger biological drive. Evidence shows that females have a higher plasticity than males. Firstly, the research by Klusmann (2006) indicated that women’s sexual motivation changes over time, in comparison to men’s sexual motivation which remains relatively constant. Secondly, women are more likely to switch between homosexual and heterosexual whereas men are either homosexual or heterosexual and will tend to remain the same for their whole life (Lippa, 2007). Religion and education have been shown to have a relationship with sexual practices (Baumeister). One hypothesis as to why sexual motivation is malleable in women may be due to women having a weaker sex drive then men, thus a motivation which is weaker can more susceptible. Another hypothesis suggested is could be due to power difference, men dominate women in aspects of physical strength, aggressiveness, socio-political and economic power (Baumeister 2000). However these views are greatly philosophical and lack any scientific evidence.

Research Issues

[edit | edit source]Due to sex being mostly a private activity, researching sexual motivation can be a complex task. The most common forms of collecting data on sexual motivation are through interviews (structured and unstructured) or questionnaires. Other methods include observation, self reports, physiological and biochemical measures and clinical evaluations (Persky, 1987). Very limited studies have involved direct observation; the research conducted by Masters and Johnson has been the most extensive in this form of data collection (Masters & Johnson, 1966). All of the data collected by Kinsey and colleagues, on their major investigation of human sexual behaviour, was by means of face-to-face interview (Kinsey et al., 1953). This causes a few issues of concern; firstly, participants may have given a socially desirable response, secondly respondents consisted of a highly homogenous sample, white and middle class, thus results cannot be generalised to the wider population. Furthermore, many studies use convenience sampling techniques by assessing young university students (Meston & Buss, 2007). This also affects generalisability of results as young students don’t have many years of sexual practice in their life and secondly may, at that stage in their life, have a promiscuous attitude towards sex.

Summary

[edit | edit source]

Sex is a part of our every day lives. Sexual motivation is the drive that generates our sexual interest. The interview study by Kinsey and colleagues was the pioneer large scale study to measure human sexual behaviour. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that sexual motivation for women is finding a man with resources and for men to find a woman who is fertile and won't make them a cuckold. Evidence supports the notion that visual stimuli assists with arousal. Theories of sexual motivation are based around incentives but also external stimuli and internal events. Testosterone plays an important role in sex drive of men and women. Two main human sexual response cycles have been proposed, Masters and Johnson's Human Sexual Response Cycle which contains four phases (excitement, plateau, orgasmic and resolution) and Kaplan's Three Phase model (desire, excitement and orgasmic). Empirical evidence shows that males have a stronger sex drive than women, men are more inclined to think about sex more, want more sexual partners, masturbate more, maintain a stronger sex drive in a long term relationship, and have a strong sex drive throughout most of their lives. Pheromones were once thought to be involved syncing of female menstrual cycle and subsequently be involved with human sexual motivation. Research on pheromones, however, seems to be inconclusive and requires more investigation. The psychology of sexual motivation shows four main factors for reasons why people engage in sexual intercourse, these being physical, goal attainment, insecurity and emotional. Sociocultural influences have been shown to effect sexual motivation, particularly in woman. The term used to describe the malleability of sexual motivation is erotic plasticity. Finally, research issues in sexual motivation are mainly due to the private nature of the topic.

{{Hide in print|

Quiz

[edit | edit source]Now for a quiz to test your knowledge on the chapter of sexual motivation.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Sexual Motivation and Adultery (Textbook chapter)

- Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Motivation (Textbook chapter)

- Gender Differences in Sexual Motivation (Textbook chapter)

- Motivation and Mate Seeking (Textbook chapter)

- Sexual Motivation and Promiscuity (Textbook chapter)

- Motivation and Sex Offenders (Textbook chapter)

- Emotion and Sex (Textbook chapter)

References

[edit | edit source]Arnow, B. A., Desmond, J. E., Banner, L. L. Glover, G. H., Solomon, A., Polan, M. A. Lue, T. F., & Atlas, S. W. (2002). Brain activation and sexual arousal in healthy, hetersexual males. Brain, 125, 1014- 1023.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 347. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=3159024&site=ehost-live

Baumeister, R. F. (2004). Gender and erotic plasticity: Sociocultural influences on the sex drive. Sexual & Relationship Therapy, 19(2), 133-139. doi:10.1080/14681990410001691343

Baumeister, R. F., Catanese, K. R., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personality & Social Psychology Review (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 5(3), 242-273. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=4802747&site=ehost-live

Buss, D. M. (1995). Psychological sex differences: Origins through sexual selection. American Psychologist, 50(3), 164-168. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.50.3.164

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204-232. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204

Kalat, J. W. (2009). Biological Psychology (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Kaplan, H. S. (1979). Disorders of Sexual desire: and other new concepts and techniques in sex therapy. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia, PH: W. B. Saunders Company.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia, PH: W. B. Saunders Company.

Klusmann, D. (2002). Sexual motivation and the duration of partnership. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31(3), 275-287. doi:10.1023/A:1015205020769

Klusmann, D. (2006). Sperm competition and female procurement of male resources as explanations for a sex-specific time course in the sexual motivation of couples. Human Nature, 17(3), 283-300. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=23002597&site=ehost-live

Kohl, J. V., & Francoeur, R. T. (1995). The scent of Eros: Mysteries of Odor in Human Sexuality. New York, NY: Continuum.

La Trobe University. (2002). Sex in Australia: Summary findings of the Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20080822065544/http://www.latrobe.edu.au/ashr/papers/Sex%20In%20Australia%20Summary.pdf

Lippa, R. A. (2007). The relation between sex drive and sexual attraction to men and women: A cross-national study of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(2), 209-222. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9146-z

Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human Sexual Response. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(4), 477-507. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2

Miller, M. C. (2006). Human pheromones Harvard Medical School Health. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=22748133&site=ehost-live

Missildine, W., Feldstein, G., Punzalan, J. C., & Parsons, J. T. (2005). S/he loves me, S/he loves me not: Questioning heterosexist assumptions of gender differences for romantic and sexually motivated behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 12(1), 65-74. doi:10.1080/10720160590933662

Myers, D. G. (2004). Psychology (7th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers

Persky, H. (1989). Psychoendocrinology of human sexual behavior. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers.

Pfaus, J. G. (1999). Revisiting the concept of sexual motivation. Annual Review of Sex Research, 10, 120. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=2909823&site=ehost-live

Regan, P. C. (1999). Hormonal correlates and causes of sexual desire: A review. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 8(1).

Schank, J. C. (2006). Do human menstrual-cycle pheromones exist?. Human Nature, 17(4), 448-470. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=26579744&site=ehost-live

Schmitt, D. P., Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (2001). Are men really more 'oriented' toward short-term mating than women? Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 3(3), 211. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=6711916&site=ehost-live

Sprague, J., & Quadagno, D. (1989). Gender and sexual motivation: An exploration of two assumptions. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2(1), 57-76. doi:10.1300/J056v02n01_05

Stellar, E. (1994). The physiology of motivation. Psychological Review, 101(2), 301. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=9407014784&site=ehost-live

Toates, F. (2009). An integrative theoretical framework for understanding sexual motivation, arousal, and behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 46(2), 168-193. doi:10.1080/00224490902747768

Wentland, J. J., Herold, E. S., Desmarais, S., & Milhausen, R. R. (2009). Differentiating highly sexual women from less sexual women. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 18(4), 169-182. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=47878338&site=ehost-live

External links

- Study offers peek at sex, American-style

- Sex in Australia

- Sexual Health Surveys

- Random Facts About Sex

Multimedia presentation feedback

|

The accompanying multimedia presentation has been marked according to the marking criteria. Marks are available via the unit's UCLearn site. Written feedback is provided below, plus see the general feedback page. Responses to this feedback can be made by starting a new section below. If you would like further clarification about the marking or feedback, contact the unit convener. |

Overall[edit source]

|