Motivation and emotion/Book/2011/Sleep and happiness

What is effect of sleep on happiness?

| This page is part of the Motivation and emotion book. See also: Guidelines. |

| “ | If sleep does not serve an absolutely vital function, then it is the biggest mistake the evolutionary process has ever made.

|

” |

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Sleep is a part of everyday life for humans and is one of the basic needs that are required for survival. Sleep affects so many parts of our lives including our emotions, cognitions and behaviour. Problems with sleep can also lead to sleep disorders and psychological disorders. Some questions this chapter will seek to answer is what is sleep, how does it affect emotions, and overall what is the effect of sleep on happiness? This chapter will also seek to identify how we may improve sleep and in turn improve happiness.

What is sleep and how does it work?

[edit | edit source]

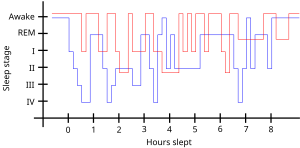

Stages of sleep[edit | edit source] Sleep in humans has been classified into 2 main categories, Non Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep. NREM can be further broken down to four sub-stages from stages 1 to 4. In humans, sleep patterns cycle through REM sleep and the four stages of NREM sleep around every 90 minutes (See Figure 2). This cycle remains fairly consistent throughout the night, however NREM stages 3 and 4 will be prominent earlier in the night and NREM stages 1 and 2, and REM sleep will be more prevalent in the latter part of the night (Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009).  Sleep patterns are usually measured by the use of an electroencephalogram (EEG). EEG requires the use of electrodes being placed on an individual’s head, where brain activity can be measured. When an individual is awake 2 patterns of activity usually occur: alpha activity and beta activity. Alpha activity consists of activity of 8-12 Hz asssociated with rest and relaxation. Beta activity is activity of 13-30 Hz and is associated with individual's arousal and high mental activity (Vassalli & Dijk, 2009). When NREM stage 1 sleep begins and EEG activity starts to show the presence of theta activity which has EEG activity of 3.5-7.5 Hz (See Figure 3). This stage is the transition from being awake and the beginning of sleep (Vassalli & Dijk, 2009).  Stage 2 of NREM sleep shows theta activity, sleep spindles and K complexes (See Figure 4). Sleep spindles are short burst of waves of 12-14 Hz that occur about every 2 to 5 minutes during stages 1-4 NREM sleep. Sleep spindles have been theorised to be the mechanism involved in keeping an individual asleep. K complexes are sudden short waveforms which are only found in stage 2 of NREM sleep. K complexes are said to be the precursor of delta activity seen in stages 3 and 4 of NREM sleep. Stages 1 and 2 of NREM sleep have been less focused on and sleep deprivation does not differ much in these stages (Vassalli & Dijk, 2009).  Stage 3 NREM sleep is made up of 20%-50% of delta activity and Stage 4 is made up more than 50% of delta activity. Stages 3 and 4 are also referred to as Slow Wave Sleep (SWS). Delta activity are high amplitude waves that are slower than 3.5 Hz (See Figure 5). Stage 4 is our deepest level of sleep and if awoken in this stage we tend to act confused and hazy (Vassalli & Dijk, 2009).  REM sleep is a period of desynchronised sleep where theta activity occurs in combination with very high frequency of gamma activity which occurs at 30-80 Hz (See Figure 6). In REM sleep our bodies are paralysed while at the same time our brain is very highly active. If someone wakes up during REM sleep they are highly likely to recall what dreams were occurring and they will appear alert and active (Walker, 2009). REM vs. NREM sleep[edit | edit source]Throughout the changes of NREM and REM sleep alterations occur in neurochemistry. In NREM sleep subcortical cholinergic systems in the forebrain and brain stem become less active. Serotonergic Raphe neurons and noradrenergic locus coeruleus neuron are also reduced when comparing to levels when awake. In REM sleep aminergic systems are inhibited while cholinergic systems become more active even compared to levels when awake. This results in the brain being in a main state of being dominated by acetylcholine and deficient of aminergic modulation (Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). Different patterns of functioning also occur between NREM and REM sleep. In NREM SWS sleep the basal ganglia, brain stem, thalamic, prefrontal and temporal lobe region show significantly reduced activity. In REM sleep the parietal cortex, prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate show to be least active. While regions that show significant increase in activity in REM sleep include pontine tegmentum, the occipital cortex, the thalamic nuclei and the mediobasal prefrontal lobes. REM sleep also affects regions related to affect such as the hippocampus, amygdala and the anterior cingulated cortex (Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). Optimal sleep[edit | edit source] People vary with how much they sleep. The average person needs 7.5-8 hours sleep per night, however some people function well on 4-5 hours, and others may need 9-10 hours. The severity of the effects of sleep amount and quality one gets, is dependent on how well we can function with our daily tasks and responsibilities throughout the day. Good sleepers take usually less than 30 minutes to fall asleep and may wake up between once or twice a night (Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI), 2011a). Adequate sleep is an essential part of healthy human functioning and on the 75 trillion cells that the body comprises of. Optimal sleep patterns require the alternation of NREM sleep which comprises of about 75% of total sleep and REM sleep which comprises of about 25% which usually last for about 5 to 30min each 90 minute cycle. These sleep patterns are shown to be important in consolidation of memory processing, learning new tasks and brain restoration(Meletis & Zabriskie, 2008). Such like the 90 minute cycles that are important in our sleep, humans also have a daily rhythm in behavior and physiological processes called circadian rhythms. In humans these rhythms are controlled by mechanisms labeled as our internal clocks which cycle approximately every 24-25 hours (See Figure 7). Zeitgeber is a stimulus that resets our internal clock and in humans this is usually light from the rising of the sun. The benefits from modern technology and the use of artificial lighting and shading, allows us to delay our bedtime and waking time. This is important to optimal sleep as it recognizes the importance of a daily sleeping pattern (Carlson, 2005). Dreaming[edit | edit source] Dreaming occurs in both NREM and REM sleep, however recollection of dreams are more readily accessible when woken in REM sleep. Sigmund Freud, renowned psychoanalysist, proposed that dreaming occurred out of one’s inner conflict between our unconscious desires and prohibitions to act out these desires. This theory prescribed that content was hidden and disguised in our dreams (Carlson, 2005). Dreams which largely emerge from REM sleep contain between 75% to 95% of emotional content. It has been proposed there may be a link between what is occurring in our day to day life and emotional concerns and themes one might have. Dreams have also said to have a connection to our neurological state and recovery from emotional conflict and trauma (Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). Dreams occurring in REM sleep show an increased activation of our visual and sleep systems. During REM sleep muscular paralysis occurs, which stops our body from physically acting out our dream. This is why during our dreams we can see visual images and feel sensations of movement that feel very real (Carlson, 2005). |

What is happiness?

[edit | edit source]

Definitions of happiness[edit | edit source] Everyone talks about the concept of happiness, however what it is and how we define it is more difficult to explain. Two distinct definitions of happiness have been proposed (Jacobsen, 2007):

The first definition describes moments such as joy and bliss that many people define as happiness. These are seen in individuals as our core emotions and daily moods. The second proposed definition seems to talk about happiness as a lifestyle. The Dalai Lama refers to this happiness as a lifelong process where we moderate emotions such as selfish desires, anger, greed and negativity and cultivate emotions of compassion, kindness and humility. This theory is closely related to the humanistic approach to happiness where theorists such as Abraham Maslow talk about the idea of self actualisation and hierarchy of needs. In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, he proposes that we need to fulfil basic physiological needs such as sleep, before we can attain other needs such as safety or love and the end result of self actualisation (Jacobsen, 2007). This chapter focuses on happiness as defined by emotions and moods. Core emotions and moods[edit | edit source]The debate over emotions about what they are and how they are formed has a diverse history. Emotion is a multidimensional phenomenon and entails a number of elements and dynamics. Emotion is a combination of feelings, arousal, purpose and social expression as a reaction to some eliciting event (Reeve, 2009).  Happiness as joy is a core emotion that is seen as something people strive for and pursue throughout their life. Happiness is said to be universally expressed in the same way by all humans. However, what makes people happy changes from each individual. The main theory of happiness is when an individual achieves a desirable outcome such as personal achievement, receiving love and affection, pleasurable sensations, interpersonal pleasure, progressing towards ones goals (Ekman, 1993). Happiness facilitates our social interaction through the way we behave and our facial expressions. This is a pattern as it creates an ongoing cycle of attracting more social interaction and becoming happier. Happiness also has a soothing effect on our psychological distress and we deal with situation more positively when we are happier (Reeve, 2009). Moods are stated to be a long lasting version of emotions. This means that a person has a general long lasting affect over the day, while still having a number of different emotions throughout the day. In moods, happiness can be described as positive affect. When exploring psychological disorders and how it affects happiness, people’s moods are the focus (Reeve, 2009). |

How does sleep effect happiness?

[edit | edit source]

Emotional regulation[edit | edit source] A study completed by Yoo, Gujar, Hu, Jolesz and Walker (2007) looked at healthy young adults and the effects sleep deprivation on emotional brain reactivity. The study used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to see if there were any differences in participants who had one night of sleep deprivation compared to those who didn’t, the control group. The study looked specifically at whether there were differences in these groups were seen when aversive stimuli were presented through visual goggles. Results showed that both groups had significantly increased activity in the amygdala when presented with the aversive stimuli. In the sleep-deprived participants the amygdala showed a 60% increase in activation than those in the control group. The volume of the amygdala activation was 3 times larger in the sleep deprived group compared to the control group. These results suggest that when presented with aversive stimuli those who are sleep deprived have a higher activation in the amygdala. The amygdala plays a large role in emotional reactivity (Yoo et al., 2007). Yoo et al. (2007) extended this study to look at differences between the sleep deprived group and the control group in the amygdala’s connections to other part of the brain. The results showed when shown aversive stimuli, the control group there were significant stronger connections between the amygdala and the Medial Prefrontal Cortex (MPFC), when compared to the sleep deprived group. While results showed the sleep deprived group showing stronger connections between the amygdala and the autonomic activating centre’s of the brainstem. The MPFC plays a large role in learning of response to their outcomes and perceived control beliefs. Yoo et al. (2007) showed higher connectivity between the MPFC and amygdala when presented with aversive stimuli in participants who slept. This supports the idea that the sleep allows this connection to be reset and govern more appropriate decision making when the amygdala is activated. This was also supported by the increased connection between the amygdala and brainstem in sleep deprived participants. This supports the idea that with appropriate sleep our emotions are more regulated through learnt response-outcomes and we won’t be as quick to act when presented with aversive stimuli. This shows support for sleep and its effects on happiness (Yoo et al., 2007). Emotional memory encoding[edit | edit source]Recent investigations examined sleep and the formation of emotional and neutral memories. In this recent study participants slept normally or were sleep deprived for 36 hours (Walker & Tharani, 2009 cited in Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). They were then presented with a learning session that was composed of emotionally negative, positive or neutral words. Results showed that the sleep deprived group showed a 40% deficit in memory encoding than the normal sleep group, when looking at all types of stimuli. When stimuli type was separated, as expected there was higher memory encoding in positive and negative stimuli on average in participants, when compared to the neutral stimuli. Results also showed that when looking at the positive stimuli group the normal sleep group showed 59% higher memory encoding when compared to the sleep deprived group. Interestingly there were no significant differences between the normal sleep and the sleep deprived group when presented with the negative stimuli (Walker & Tharani, 2009 cited in Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). This study supports the idea that with appropriate sleep, individuals are able to encode memories that are emotionally positive or negative better than neutral stimuli. While the evidence shown suggests sleep deprived individuals encode emotionally positive stimuli at a significantly lower effiency level than those in the normal sleep group (Walker & Tharani, 2009 cited in Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). This evidence is linked in with the study by Yoo et al. (2007) as discussed in emotional regulation which shows the effects appropriate sleep and sleep deprivation and its effects on the amygdala and surrounding brain regions. REM sleep is seen to be particular important in emotional memory encoding and the particular brain regions that sleep effects. REM sleep also shows a link to emotional memory enhancement in the long term and neuroplasticity development in this area. This will be discussed in more detail in emotional memory consolidation and the link between the amygdala and the hippocampus which is important for emotional memory processing (Walker & Van Der Helm, 2009). Emotional memory consolidation[edit | edit source]Emotions are known to play not only a major role in memory encoding but also memory consolidation. The importance of REM sleep has been explored and is theorised to provide a therapy or recovery for achieving optimal affective states. This is shown particularly in the connection between the amygdala and hippocampus. It has been theorized that theta activity in REM sleep provides a network in our brain that allows our emotional events and memory to be processed and integrated harmoniously. As stated earlier REM sleep shows lower activity of aminergic systems, which is particularly important to emotional memory encoding and consolidation. This is because high aminergic activity, specifically noradrenergic input from the locus coeruleus has been linked to high levels of stress and anxiety. So during REM sleep our brains can process our emotions and memories in a constructive manner without the influence of aminergic systems (Walker, 2009). This shows how appropriate sleep can lead to more positive emotional memory processing. A study by Hu, Stylos-Allan and Walker (2006) looked at differences between emotional memory consolidation with participants with 12 hour sleep deprivation and no sleep deprivation, the control group. Both groups were presented arousing and neutral stimuli before sleep deprivation or sleep. Twelve hours later after sleep deprivation or sleeping, participants were shown the same picture or a new picture. Results show that recognition accuracy was 42% higher in the control group than the sleep deprived group. This places more support towards how our sleep, particularly REM sleep plays an important role in emotional memory consolidation (Hu et al., 2006). |

Sleep & psychological disorders

[edit | edit source]|

Sleep has a profound effect on emotions and happiness. Sleep can also get to a stage where it can become disordered due to certain issues and individuals sometimes meet criteria for a sleep disorder. In this section we will look particularly at primary sleep disorders. However, we will also look into sleep disorders related to another mental disorder. These are usually mood and anxiety disorders (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000). This identifies how our moods can affect our sleep and our sleep can affect our moods. Sleep disorders[edit | edit source]Sleep disorders are divided into 2 main categories: Dyssomnias and parasomnias (APA, 2000). Dyssomnias are defined by disturbances in the amount, timing and quality of sleep. Dyssomnias include:

Parasomnias are defined by abnormal behaviour and physiological events during sleep. These include:

It is recommended if anyone has significant symptoms to see a physician or sleep specialist and have a polysomnography completed. A polysomnography, also known as a sleep study, includes an EEG and other instruments that measure eye movement, skeletal muscle activity, heart rhythm, leg movement, air flow and snoring. Mood disorders[edit | edit source] Depressive disorders The most commonly diagnosed and severe depressive disorder is called major depressive episode. The Diagnostic and Statstical Manual of Mental Disorder, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for major depressive episode describe a depressed mood lastly for at least 2 weeks cognitive symptoms such as low concentration and worthlessness, physical symptoms such as changes in appetite, energy levels and sleep patterns (APA, 2000). This is also accompanied by loss in interests in things, not experiencing pleasure from life and decreased interaction with people. The specific symptom we want to focus on is the sleep changes which the DSM-IV-TR states as: insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day. The DSM-IV-TR prescribes that for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder that this may be one of the symptoms, but is not necessary for a diagnosis (APA, 2000). Other depressive disorders such as major depressive disorder (recurrent), dysthymic disorder and double depression have similar diagnostic criteria but differ in number of depressive episodes, severity of symptoms and length of symptoms (APA, 2000). Other mood disorders Some of the other mood disorders that include disordered sleep in their criteria, which you may have heard of, include (APA, 2000):

Anxiety disorders[edit | edit source]Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) The DSM-IV-TR defines GAD as when an individual finds it difficult to control their worry, excessive worry or anxiety occurs more days than not for at least 6 months and this excessive worry cause’s significant impact on social, occupational and daily life. Symptoms include some of the following: restlessness, easily fatigued, difficulty concentration, muscle tension, irritability and sleep disturbance. Sleep disturbance in this criterion is defined as difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep or restless sleep. Again sleep disturbance may present in GAD, but is not mandatory in its diagnosis (APA, 2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) PTSD is a long lasting emotional disorder that can occur after a variety of traumatic events including physical assaults, car accidents, natural disasters or death of close relation. Symptoms may include flashbacks, avoiding any details of the traumatic event, physiological reactivity to cues of the traumatic event, feeling of detachment, irritability, difficulty concentrating and hyper vigilance. One symptom is difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, but again this can be a symptom of PTSD but is not a requirement in diagnosis (APA, 2000). |

How do we improve sleep?

[edit | edit source]

Psychological treatments[edit | edit source]Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) involves correcting cognitive errors, substituting negative thoughts to more realistic thoughts and looking at cognitive appraisals and schemas to the way we behave. CBT has seen to be effective in the treatment of depression, anxiety and insomnia (Barlow & Durand, 2005). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a new wave that has come out of development of CBT. ACT is based on the notion of acceptance and mindfulness. More research is currently being completed on its effectiveness in treatment with psychological disorders. There has been some research to suggest that ACT is effective in treating depression and anxiety (Chapman, 2006). Sleep hygiene strategies are incorporated into some therapies; however this is something we can improve on our own. Sleep hygiene is the term that describes good sleeping habits. There is research that suggests that good sleep hygiene can lead to long term solutions in sleep difficulties. These strategies include (CCI, 2011b):

Medication[edit | edit source]There are a range of medication use include anti-depressants, anti-anxiety drugs and anti-psychotics. These have seen to help with depression, anxiety and some sleep disorders. These drugs have different side effects and precautions should be taken when taking them (Peterson, Rumble & Benca, 2008).  Alternative approaches[edit | edit source]Alternative approaches that people use include (Bootzin & Epstein, 2011):

|

Sleep scales

[edit | edit source]|

Please click on a scale to find out how your rate on these sleep scales.

|

Summary

[edit | edit source]Overall this chapter discusses the differences in REM and NREM sleep. We have talked about the neurophysiology of sleep, optimal sleeping patterns and dreaming states. The chapter describes happiness, emotion and mood. We discussed sleep and its effects on emotions and what problems can arise with disordered sleep. Lastly, strategies have been provided for anyone that has trouble with sleep and sleep scales have been linked into the page which helps people identify sleep problems. Links have been provided to other pages for information on sleep, strategies and sleep services. Good night!

See also

[edit | edit source]- Sleep and negative emotions (Book chapter, 2011)

References

[edit | edit source]Barlow, D. H. & Druand, V. M. (2005) Abnormal psychology: An integrative approach. CA, Thomson Wadsworth.

Bootzin, R. R. & Epstein, D. R. (2011) Understanding and treating insomnia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 435-458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091516

Carlson, N. R. (2005) Foundations of physiological psychology. Sydney: Pearson Education, Inc.

Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI). (2011a) Facts about sleep. Retrieved November 5, 2011 from http://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/docs/Info-facts%20about%20sleep.pdf

Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI). (2011b) Sleep hygiene. Retrieved November 5, 2011 from http://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/docs/ACF1946.pdf

Chapman, A. L. (2006) Acceptance and mindfulness in behaviour therapy: A comparison of dialectical behaviour therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy. International Journal of Behavioural and Consultation Therapy, 2, 308-313. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=03efcba2-6257-4082-9851-2a38f9e547e4%40sessionmgr104&vid=5&hid=119

Ekman, P. (1993) Facial expression and emotion. American Psychologist, 48, 384-392. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.4.384

Hu, P., Stylos-Allan, M., & Walker, M. P. (2006) Sleep facilitates consolidation of emotional declarative memory. Psychological Science, 17, 891-898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01799.x

Jacobsen, B. (2007) What is happiness? Existential Analysis: Journal of the Society for Existential Analysis, 18, 39-50. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=47ee5b8d-c4f1-42e6-b494-905de9e3c8c6%40sessionmgr104&vid=21&hid=126

Meletis, C. D., & Zabriskie, N. (2008) Natural approaches for optimal sleep. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 14, 181-188. doi: 10.1089/act.2008.14402

Peterson, M. J., Rumble, M. E. & Benca, R. M. (2008) Insomnia and psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 38, 597-605. Retrieved from: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=725a8d61-dbf2-48a6-8df9-d00acec0ed7e%40sessionmgr111&vid=4&hid=119

Reeve, J. (2009) Understanding motivation and emotion. NJ : John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Vassalli, A., & Dijk, D. (2009) Sleep function: Current questions and new approaches. European Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 1830-1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06767.x

Walker, M. P. (2009) The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1156, 168-197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x

Walker, M. P., & Van Der Helm, E. (2009) Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 731-748. doi: 10.1037/a0016570

Yoo, S. S., Gujar, N., Hu, P., Jolesz, F. A., & Walker, M. P. (2007). The human emotional brain without sleep—A prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Current Biology, 17, R877–R878. Retrieved from: http://walkerlab.berkeley.edu/reprints/Yoo-Walker_CurrBiol_2007.pdf

External links

[edit | edit source]- University of Canberra - Faculty of health clinics: Sleep lectures from September - November 2011.

- University of Canberra - Faculty of health clinics: Sleep clinic.

- Sleep and Lifestyle Solutions.

- Sleep and negative emotions.

- Handling stress - The effect of stress on emotion and how emotion can be managed in challenging situations.