Motivation and emotion/Book/2024/Intentional pregnancy motivation

What motivational factors contribute to intentional pregnancy?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

While still in their early twenties, Australian couple Jess (34) and Steve (32) began their first round of In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF). Now, eight years later, they have gone through 13 rounds of IVF without achieving a successful pregnancy, and the financial and emotional toll has been immense. After countless appointments with fertility specialists, all the rounds of IVF, and many cross-country trips for egg collection or special medications, the couple estimates that the total financial toll exceeds $120,000. Even after all this physical, emotional, and financial turmoil, the couple says they are not ready to give up and hope to fall pregnant soon (Honeybone, 2022). This continued faith could be attributed to expectancy theory as the couple is motivated by the belief that the more effort they exert, the more likely they are to succeed. |

Intentional pregnancy refers to the conscious and informed decision to conceive one's own biological child and carry them to term. This excludes unplanned pregnancies, pregnancies via force, and child pregnancy. This chapter only pertains to the motivations behind wanting biological children via being personally pregnant.

Pregnancy is often called the miracle of life due to its value and complexity, but it comes with challenges. Even in the best cases, women can experience unpleasant symptoms, and 46% of pregnancies have at least one complication (Danilack et al., 2015). Although rare in developed countries, risks like permanent damage or death still exist. Despite this, millions of women choose to become pregnant, often more than once.

Infertility and illness can make pregnancy difficult, but treatments like IVF have helped many. However, these treatments are expensive and physically demanding. Women with preexisting health issues or disabilities are at a 50% higher risk of severe complications, yet many still choose to conceive (Huynh & Bock, 2021). Even after miscarriages and the trauma and grief they bring, 76% of women try again within six months, showing their strong motivation to have a successful pregnancy (Schliep et al., 2016).

This chapter examines why women choose to get pregnant despite the risks. It explores the psychological, biological, cultural, religious, and social factors that drive the desire to conceive, carry, and give birth.

|

Biological motivation

[edit | edit source]At first, it might seem like pregnancy is just about the sex drive, but the reasons for choosing to get pregnant are more complicated. Technology, psychology, and biology have shown that various factors can influence the decision to conceive. These factors include aspects like hormones and evolution which create strong instincts that can make women want to be pregnant.

Hormonal

[edit | edit source]There is no solid evidence that a specific hormone directly causes the desire to have a baby. "Baby fever" likely results from a combination of factors, including hormones. While sex drive and hormones can lead to unplanned pregnancies, hormones like oxytocin play a bigger role in making thoughtful decisions about pregnancy. Oxytocin boosts relationship satisfaction, which may increase the desire to conceive. In happy relationships, oxytocin fosters a cycle of love and closeness, influencing pregnancy decisions (Algoe et al., 2017). Research shows that women are 83% more likely to have multiple pregnancies if they are happy in their relationship (Fan & Maitra, 2013).

After conception, the next step in planned pregnancy is deciding to continue it. Pregnancy feels different for every woman. Some may find it easy, while others struggle. The body produces hormones like oxytocin to help the mother bond with the baby. This bond can make the mother more likely to continue the pregnancy, even with negative symptoms (Prevost et al., 2014). The connection during pregnancy may also be why some women prefer being pregnant over other ways of becoming a mother. Oxytocin also strengthens the maternal instinct, increasing the desire to nurture and protect.

From a psychological view, drive reduction theory says human behaviour is motivated by reducing internal tension caused by unmet needs (Stagner, 2024). This process helps restore balance, or homeostasis. However, the theory has limits because it only focuses on biological needs. Environmental and social factors can also be a big influence on behaviour. In intentional pregnancy, a woman may feel a hormone-driven desire for a biological baby, seeking satisfaction. The need to fulfill maternal and survival instincts can also affect her decision to become pregnant.

Evolutionary

[edit | edit source]

From an evolutionary view, the main biological reason for pregnancy is to continue the species and pass on genes. This drive comes from instinct, shaped by environmental and genetic factors. The survival instinct is the strongest human instinct. This extends beyond personal survival to ensuring humanity and one's genetic code continue lives on. This can create a strong urge to reproduce. Human intelligence allows people to override such urges when making choices. Today, the survival instinct tied to pregnancy focuses more on saving genetic material than humanity's survival. Couples often intentionally conceive because they value the genetic connection with their children (Rulli, 2016). Studies also suggest parents’ bond easier with babies who resemble them or their partner (Dolinska, 2013).

While the maternal instinct can appear in different contexts outside pregnancy and isn’t felt by all women, it often effects the decision to conceive and carry a biological child (Robinson & Stewart, 1989). The maternal instinct, part of the protective and survival instincts, creates deep biological and psychological drives to care for and protect their babies.

Psychologically, the Instinct Theory of Motivation says that behaviour is driven by inborn instincts (Epstein, 1982). These instincts help the species survive, like those in animals. However, critics of this theory raise the nature vs. nurture debate. Arguing that not all instincts are the same for everyone. Some, like the maternal instinct, can be shaped, encouraged, or weakened by environmental factors.

|

Cultural/Religious motivation

[edit | edit source]Culture and religion are strong motivators for pregnancy and are often intertwined. In many cultures, religion shapes values, beliefs, and practices, while culture influences how religion is practiced. Both play a significant role in the decision to become pregnant, affecting support, expectations, community status, and access to contraception.

Traditions and Teachings

[edit | edit source]In some cultures, pregnancy and childbirth are seen as crucial for preserving traditions, language, and values, especially for minority cultures. For groups like Aboriginal Australians and Native Americans, having biological children helps recover from past losses and ensures their cultural and religious identity is passed to future generations. This desire to maintain cultural traditions is linked to the survival instinct. Even in non-endangered cultures, parents may feel motivated to have children to continue their cultural legacy.

Many cultures around the world have specific traditions and rituals surrounding pregnancy and childbirth. These cultural practices are often seen as rites of passage that all mothers must go through. Religious beliefs are often intertwined with these traditions as the practices surrounding pregnancy are often done for spiritual reasons such as good luck, warding off evil spirits, and contacting ancestors (Boules, 2020). This could create a fear of missing out or being excluded which would act as a motivating factor for women to choose to become pregnant.

This desire is better explained by belonging motivation which states that humans desire to feel accepted, valued, and included in relationships and communities (Hoyle et al., 2024). Being able to participate in these traditions and rituals could be strong motivators for pregnancy due to this motivation to belong.

Religious teachings from texts like the Bible, Torah, and Quran often emphasize the importance of procreation as a divine command (Blume, 2024). Islam, Christianity, and Judaism encourage believers to have children to continue the faith and build strong communities. These teachings can motivate believers to pursue pregnancy, aligning with their faith. Some religions also restrict or ban contraception and abortion, as seen in the Roman Catholic Church, and to some extent, Islam and Judaism (Schenker & Rabenou, 1993).

While many religious women choose pregnancy as part of their faith, not all have the freedom to make this choice due to external pressures or lack of information. This raises concerns about reproductive freedom, which is key to intentional pregnancy. Therefore, pregnancy motivated by religion should be based on personal choice and free will.

Holiness and Status

[edit | edit source]Many religions view pregnancy and childbirth as sacred acts that bring new life into the world, inspiring individuals to see them as holy and worthy of respect. This belief can strongly motivate people to pursue pregnancy. In Yoruba culture, pregnancy elevates a woman's status as she is considered divinely blessed, and motherhood is highly honoured (Musie et al., 2022). Similarly, in Australian First Nations culture, pregnancy is deeply respected, with traditional rituals and blessings given to support both mother and baby.

Other African cultures also prioritize the spiritual well-being of pregnant women, ensuring they receive the best food, gifts, and care, while partners abstain from sex to protect the holiness of both the mother and child (Musie et al., 2022). These cultural and religious practices highlight the sacred nature of pregnancy across various traditions. Some religious traditions teach that pregnancy can lead to spiritual growth and a deeper connection with the divine. The belief in a higher power and the possibility of spiritual enlightenment can be a powerful motivator for women to experience pregnancy.

In Iranian culture and various other Muslim traditions, the development of a soul within the mother's body is believed to enhance spiritual awareness and strengthen her connection to God (Manookian et al., 2019). This connection is thought to bring greater joy in prayer and a deeper understanding of the Quran. From a psychological standpoint, the Incentive Theory suggests that behaviour is motivated by the desire for rewards or positive outcomes rather than internal drives or instincts (Killeen, 1981). These rewards don't need to be tangible. In this context, women may weigh the risks of pregnancy against the perceived spiritual benefits, believing that their faith will protect them throughout the process, which can be a strong motivator.

|

|

Social motivation

[edit | edit source]Society plays a key role in influencing pregnancy decisions through social norms, expectations, and pressures. People often base pregnancy decisions on what they view as socially acceptable. Factors like family pressure, peer influence, social status, and community support can affect the timing and motivation to conceive. Beyond cultural and religious influences, social motivation also includes factors like government, media, social movements, and security, which all contribute to the decision to have a child.

Societal Norms

[edit | edit source]

While alternative paths to motherhood, like adoption and surrogacy, are more accepted in Western societies, personal pregnancy is still viewed as the norm. Although there is general support for adoption and surrogacy, they are often considered last resorts. For instance, despite 90% of Americans expressing favourable views on adoption, only 1.2% have adopted a child (Van Laningham, 2012). Similarly, while surrogacy is supported, 60% of people believe it should mainly be used for same-sex couples or infertility (Karolina Lutkiewicz et al., 2023). This shows that societal norms around personal pregnancy and biological motherhood remain strong.

Societal norms that celebrate pregnancy and childbirth—such as baby showers, christenings, and 100-day celebrations—can create a supportive social environment that encourages women to view pregnancy as something they want to experience. These celebrations of motherhood foster feelings of community and belonging, making the idea of pregnancy feel more appealing and achievable, as women feel supported and not alone in the journey. The media also feeds into these norms as women are commonly portrayed in mothering roles in moves, tv, and advertisements.

From a psychological standpoint, these social norms around pregnancy and motherhood, observed from childhood through adulthood, can reinforce the desire to become pregnant. This aligns with social learning theory, which suggests that behaviour, opinions, and desires are influenced by observing others and the social environment (Bandura et al., 1963). When a society shows positive reinforcement and approval for motherhood, it can motivate women to pursue pregnancy.

Social Expectations and Pressure

[edit | edit source]Societal expectations around gender roles often encourage women to become mothers, with motherhood seen as a key part of their identity. Despite progress in how society views women's roles, childless women still face social stigma. A report by SBS Spain highlights how many childless women feel silently judged, as motherhood is still viewed as a way for women to fulfill their social role. This fear of judgment can push some women to choose pregnancy, even if they don't fully desire it.

After having one child, women often face additional pressure to have more, with societal judgments about having only one child, as explored in an article by the Sydney Morning Herald. In some Asian and African societies, the pressure to provide many children, especially for their husbands, is reflected in population trends. In extreme cases, these expectations can be life-threatening, and the autonomy to choose pregnancy is severely limited, raising the question of whether these pregnancies are truly voluntary.

In some societies, social status and prestige are closely tied to having biological children, especially male children. This is particularly true in many Asian cultures, where carrying on the family name and lineage is highly valued. Since sons are seen as the only way to continue the family legacy, women are often encouraged to have multiple pregnancies until a son is born. In these cases, other forms of motherhood, like adoption, are not considered, as personal pregnancy is viewed as the only way to ensure the survival of the bloodline. Producing many sons is seen as a way for women to honour their families, which can strongly motivate the desire to conceive.

Social Movements

[edit | edit source]Modern feminism and reproductive laws have greatly influenced women's pregnancy choices by promoting personal autonomy. Feminism has empowered women to see pregnancy as a personal choice, not a social obligation, allowing for more control over reproductive decisions. It also supports balancing careers and motherhood, making the decision to have children more about personal desire than societal pressure. On the other hand, some women, inspired by feminism, reject pregnancy as a burden or a tool for social change. For example, South Korea’s 4B movement involves women avoiding dating, marriage, and reproduction in response to sexism. This has impacted the country's birth rate. Overall, feminism has shifted societal attitudes, giving women more freedom to decide whether and when to have children.

Government laws can have a huge impact on society, especially when it comes to pregnancy. Laws that limit or ban reproductive healthcare can influence women's decisions about becoming pregnant. For example, the overturning of abortion laws through Roe vs Wade created new challenges for women. Women now must consider what would happen if they faced complications during pregnancy. Studies show that after the abortion ban, pregnancy-related deaths went up by 33% (Stevenson, 2021). This may discourage some women from deciding to become pregnant due to the risks and lack of control. On the other hand, countries like the Netherlands, which support reproductive healthcare. They have very low rates of unwanted pregnancies, maternal mortality, and abortions (Hardon, 2003). In such environments, women who feel safe and supported are more likely to decide to conceive.

|

|

Additional Psychological Perspectives

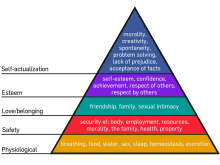

[edit | edit source]Psychological theories aim to explain human behaviour, decisions, and thought processes. In the context of intentional pregnancy, theories related to biological instincts, social influences, emotional fulfillment, and personal reward provide insight. Broader theories like Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Cognitive Dissonance Theory, and Expectancy Theory help explain the complex motivations behind the decision to become pregnant, offering a deeper understanding of these factors.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

[edit | edit source]Maslow’s theory suggests that human behaviour is driven by a hierarchy of needs, starting with basic survival and ending with self-actualization. In between are needs for safety, love, belonging, and self-esteem, all of which pregnancy can help fulfill, making it a strong motivator (Maslow, 1943).

Once basic needs are met, people seek safety and security. Women in safe and supportive relationships may want to have children because it provides a sense of security and may strengthen their bond. In some cultures, having biological children is also seen to ensure care in old age.

Love and belonging are powerful motivators for pregnancy. The desire for close family bonds, a strong relationship with a partner, and the need to care for and love a baby can lead women to conceive. While this need can be met in other ways, many women find it easier to bond with biological children, especially during pregnancy (Rulli, 2016).

Self-esteem and self-actualization also influence pregnancy decisions. The sense of achievement from pregnancy and childbirth can boost self-esteem, and some women see pregnancy to grow personally, achieve life goals, or find purpose and meaning. The desire to fulfill their body’s potential through pregnancy can be a strong motivator.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory

[edit | edit source]Cognitive Dissonance Theory suggests that when people have conflicting beliefs or actions, it creates mental discomfort, which they are driven to resolve (Eysenck, 1963). In pregnancy, this can explain how women manage conflicting feelings about wanting a baby but fearing the challenges. These fears aren't always physical; financial strain and career sacrifices also play a role. For women with illness or disabilities, the conflict can be stronger due to higher physical risks. In such cases, survival instincts may clash with maternal instincts—the desire for self-preservation versus the yearning for a baby.

To reduce this discomfort, women may justify their choices to align with their desires. Even after deciding, cognitive dissonance can persist. A woman who becomes pregnant may still worry about the sacrifices, while one who chooses not to might feel regret or question her decision.

Expectancy Theory

[edit | edit source]Expectancy Theory explains motivation by suggesting that actions are driven by the expected outcome (Miner, 2005). In the case of pregnancy, it means a woman’s decision to become pregnant is based on what she expects to gain from pregnancy and motherhood. For women facing infertility or miscarriage, this theory may explain why they keep trying after failed attempts. They may believe that their continued effort will eventually lead to success. Thinking that if they try hard enough, they will reach their goal, and their goal will be worth it even if it takes various tolls on them.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Intentional pregnancy is influenced by various factors, including biology, culture, religion, society, and personal choice. Each person has unique reasons for wanting to become pregnant, with some influenced more by one factor than others. Biology triggers natural instincts and urges, while culture and religion shape the timing and reasons for pregnancy, varying by region. Society also plays a significant role, with its own values and expectations around pregnancy. Together, these influences shape how individuals and communities think about having children. While psychology helps us understand some of the reasons behind pregnancy, there's still much we don't know about what drives this decision. Since motivations can be personal and complex, some may never be fully understood.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Drive theory (book chapter, 2023)

- Oxytocin and motivation (Wikipedia)

- Invitro fertilisation (Wikipedia)

- cognitive dissonance theory (Wikiepedia)

- Maslow's hierarchy of needs (Wikipedia)

- drive reduction theory (Wikipedia)

- oxytocin (Wikipedia)

- Social learning theory (Wikipedia)

- Roe vs Wade (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). A comparative test of the status envy, social power, and secondary reinforcement theories of identificatory learning. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(6), 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046546

Blume, M. (2024). APA PsycNet. Apa.org; American Psychology Association . https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-09624-008

Boules, Norma. (2020). Baulkham Hills Holroyd Parramatta Migrant Resource Centre Early Intervention and Perinatal Project Cultural Birthing Practices and Experiences. In Cultural Birthing Practices and Experiences. Early Intervention and Perinatal Project. https://cmrc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/cultural_birthing_practices_and_experiences.pdf

Danilack, V. A., Nunes, A. P., & Phipps, M. G. (2015). Unexpected complications of low-risk pregnancies in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 212(6), 809.e1–809.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.038

Dolinska, B. (2013). Resemblance and investment in children. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.645482

Epstein, A. N. (1982). Instinct and Motivation as Explanations for Complex Behavior. The Physiological Mechanisms of Motivation, 1(1), 25–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-5692-2_2

Eysenck, H. J. (1963). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(63)90061-8

Fan, E., & Maitra, P. (2013). Women Rule: Preferences and Fertility in Australian Households. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 13(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2012-0021

Grant, A. D., & Erickson, E. N. (2022). Birth, love, and fear: Physiological networks from pregnancy to parenthood. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 11(1), 100138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpnec.2022.100138

Hardon, A. (2003). Reproductive Health Care in the Netherlands. Reproductive Health Matters, 11(21), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02165-7

Honeybone, E. (2022, January 31). Jess and Steve have had 13 failed IVF cycles. It’s cost them $120,000. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-01/how-jess-and-steve-endured-13-ivf-cycles/100792618

Hoyle, R., Leary, M., & Kelly, K. (2024). Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior. Google Books. https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=67xcAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA400&dq=belonging+motivation&ots=DWdEFZxWuQ&sig=sfWO0e8-J2zhtAabtPLxQG-Cys0#v=onepage&q=belonging%20motivation&f=false

Huynh, L., & Bock, R. (2021, December 15). NIH study suggests women with disabilities have higher risk of birth complications and death. National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-study-suggests-women-disabilities-have-higher-risk-birth-complications-death

Karolina Lutkiewicz, Łucja Bieleninik, Jurek, P., & Mariola Bidzan. (2023). Development and validation of the attitude towards Surrogacy Scale in a polish sample. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05751-x

Killeen, P. (1981). APA PsycNet. Psycnet.apa.org; American Psychology Association . https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1982-31908-001

Manookian, A., Tajvidi, M., & Dehghan-Nayeri, N. (2019). Inner voice of pregnant women: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 24(3), 167. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_105_18

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Miner, J. B. (2005). Organizational behavior. Vol. 1 (1st ed., Vol. 1). M.E. Sharpe. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315702018/organizational-behavior-1-john-miner?refId=111230ac-29bd-4a9a-99ad-3fbe4b297838&context=ubx

Musie, M. R., Anokwuru, R. A., Ngunyulu, R. N., & Sanele Lukhele. (2022). African indigenous beliefs and practices during pregnancy, birth and after birth. National Library of Medicine , 1(6), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.4102/aosis.2022.bk296.06

Prevost, M., Zelkowitz, P., Tulandi, T., Hayton, B., Feeley, N., Carter, C. S., Joseph, L., Pournajafi-Nazarloo, H., Yong Ping, E., Abenhaim, H., & Gold, I. (2014). Oxytocin in Pregnancy and the Postpartum: Relations to Labor and Its Management. Frontiers in Public Health, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00001

Robinson, G. E., & Stewart, D. E. (1989). Motivation for Motherhood and the Experience of Pregnancy. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 34(9), 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674378903400904

Rulli, T. (2016). Preferring a Genetically-Related Child. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 13(6), 669–698. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455243-4681062

Schenker, J. G., & Rabenou, V. (1993). Contraception: traditional and religious attitudes. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 49(1-2), 15–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-2243(93)90102-i

Schliep, K. C., Mitchell, E. M., Mumford, S. L., Radin, R. G., Zarek, S. M., Sjaarda, L., & Schisterman, E. F. (2016). Trying to Conceive After an Early Pregnancy Loss. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(2), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001159

Stagner , R. (2024). HOMEOSTASIS, NEED REDUCTION, AND MOTIVATION on JSTOR. Jstor.org. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23082471?casa_token=6SOBqau4qmQAAAAA%3AxDwGfYBU4HgnF4JZq2rfZNPLK1MdTMy3A6T2zsdVU6VWkSR9ZV8mzfmRrt05TbSBmEq1pXmy4WVHRCGKSmiua_p2N8i1G3Dlx0ZKB4Hmn_DATRP73Jb2kA&seq=1

Stevenson, A. J. (2021). The Pregnancy-Related Mortality Impact of a Total Abortion Ban in the United States: A Research Note on Increased Deaths Due to Remaining Pregnant. Demography, 58(6). https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9585908

Van Laningham, J. L. (2012). Social Factors Predicting Women’s Consideration of Adoption. Michigan Family Review, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3998/mfr.4919087.0016.101

Zimmermann, B. (2023, August 8). South Korea’s 4B Movement Lowers the Birth Rate in a Fight for Gender Equality. The International Affairs Review. https://www.iar-gwu.org/blog/iar-web/south-koreas-4b

External links

[edit | edit source]- Evolutionary Perspectives on Pregnancy (Columbia University Press)

- The South Korean 4B movement (The International Affairs Review)

- Instinct theory of motivation (Explorable)

- Cultural Birthing Practices and Experiences(BHHP Migrant Resource Centre)

- Incentive theory ( Explore Psychology)

- Stigma around being childless (SBS Spain)

- single child judgment (Sydney Morning Herald)