Motivation and emotion/Book/2022/Workplace mental health training

What is WMHT, what techniques are used, and what are the impacts?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Most people spend about a third of their working lives working or doing things related to work. Millions of people report to work every day with mental health problems. Some people may only have it for a short time, while others may have it for many years or a lifetime. Mental health problems at work are disabling. They can cause serious emotional, physical, and cognitive problems for employees. Mental health issues make workers less productive and cost employers Deloitte money (McDaid et al., 2019). The Productivity Commission report on mental health (2020) in Australia found that reduced participation and absenteeism cost employers more than AU$12 billion annually. In a Canadian study by Deloitte, the return on investment for training in mental health was CA$2.18. But, a European study found that the number could be as high as $13.62 for every dollar spent on training.

There has been a lot of discussion about workplace mental health training (WMHT) at work. The main aim is to raise awareness, fight stigma, build resilience through self-care, and make workplaces conducive to good mental health. Organisations, governments, and mental health professionals have taken big steps to solve the problem, but there is still a long way to go. Given how expensive mental health problems are, WMHT is becoming a top workplace priority. WMHT can help both employees and employers become more resilient. Future interventions must consider globalised work and how different cultures are represented in the workforce.

Alex just broke up with a long-term partner. He had trouble sleeping, was depressed all the time, and found it hard to focus at work. Alex felt scrutinised, alone, and not supported at work. He started to question himself and feel bad about himself. What will Alex's boss do to show that the office is a healthy place to work? |

|

Focus questions:

|

Workplace mental health

[edit | edit source]Workplace mental health is a way to help employees feel e healthy and happy at work. Training can assist employees to build resilience at work and help employers to provide environments that support employee mental health.

What is a healthy workplace?

[edit | edit source]Early descriptions of a mentally healthy workplace was an organisation that

“maximizes the integration of worker goals for well-being and company objectives for profitability and productivity” Sauter et al. (1996)

With more research, the definition of a mentally healthy workplace has evolved. 'Heads Up' defines a mentally healthy workplace as: A workplace with a anti-discrimination policy and a culture promoting employees' mental health and well-being (see Figure 1).

European network for workplace health promotion defines a mentally healthy workplace as one that:

- Promotes practices that support positive mental health

- Reduces and eliminates psychological hazards

- Trains employees to be resilient and thrive in mentally tough conditions

- Creates a positive environment by addressing stigma and discrimination

- Supports recovery and rehabilitation after mental illness

Psychological hazards

[edit | edit source]Psychosocial hazards are workplace situations that can impair one's mental health. These dangers can also cause physical injury. Different workplaces may present different psychological risks. Safe Work Australia provides an extensive list of psychological hazards in a publication - Model Code of Practice: Managing psychosocial hazards at work.

Some of the risk factors are:

- High work demands

- Low control over work conditions

- Poor managerial/supervisory support

- Traumatic events

- Poor physical environment (ergonomics)

- Violence/aggression or bullying

- Harassment/sexual harassment

Stress, job burnout, and mental ill health are just a few of the effects on psychological health that can result from psychosocial hazards.

Workplace mental health training

[edit | edit source]As much as each person is accountable for their health, it is also important for employers to be empathetic towards employees. Post-intervention costs for treating mental illness are high. Employees should be encouraged use early intervention to build resilience and mental toughness. Initiatives addressing mental health can help employees stay longer and be at work and be more productive (McDaid et al., 2019). First, we need to find out what a healthy workplace is so we can design the strategies and training used for WMHT. The common goal of mental health training programs is achieve and sustain healthy workplaces.

Healthy workplace practices

[edit | edit source]WMHT is based on developing healthy workplaces. A meta-study by Grawitch et al. (2006) identified five key features of a healthy workplace:

- Work-life balance

- Employee growth and development

- Health and safety

- Recognition

- Employee involvement

Further research expands features to a comprehensive list of nine key elements. Discussed in the table below.

| Key elements | Description |

|---|---|

| Prioritising mental health | Increase understanding and awareness by providing mental health education and encouraging open communication. |

| Trusting fair and respectful culture | All employees should learn to treat everyone with honesty and respect. |

| Open and honest leadership | Practicing effective leadership give your team members a sense that they are all working towards the same goals. |

| Good job design | Make sure people are physically safe, give them jobs that fit their skills, and give them a choice about when they work. |

| Workload management | Set goals that can be achieved in a reasonable amount of time. |

| Employee development | Create an environment where employees are regularly supported, trained, recognised, and rewarded. |

| Inclusion and influence | Allow employees to take control of their work and have a say in how the organisation makes decisions. |

| Work/life balance | Recognise the importance of work-life balance. Support employees to balance family, work, and other things they need to do. |

| Mental health support | Managers and staff stay sensitive to employees' mental health problems. No matter what caused the problem, make sure support is readily available. |

Responsibilities

[edit | edit source]According to Kelloway (2017), any training program must address the four general principles:

- Corporate commitment to improving psychological health and safety

- Leadership commitment to the issue

- Employee involvement in identifying workplace issues and the design of intervention programs

- Confidentiality of individuals

Based on Kelloway's theory, responsibilities can be divided into individual and corporate factors. The nature of the intervention program will depend on the presence or absence of responsibilities.

Employee factors

[edit | edit source]Individual factors include what people can do to help themselves to deal with mental health problems. These can include:

Self-care

[edit | edit source]Self-care must be a top priority and a necessary part of functioning (Posluns and Gall, 2020). Self-care can help people avoid problems like burnout, stress, and depression (Barnett et al., 2007) (see Figure 3). People can take care of themselves by doing things they enjoy or by practising Mindfulness, Yoga, and Meditation.

Developing coping strategies

[edit | edit source]The work environment can include stressors such as job insecurity, hazardous working conditions, heavy workload, and the threat of violence. Employees can develop coping strategies to address the issues through WMHT (Chopra 2009).

Building communication channels

[edit | edit source]Employees, managers, and supervisors need to figure out the psychological risks. They must set up communication channels to discuss and address the issues.

Professional development

[edit | edit source]Professional development involves building knowledge and skills. Professional development is necessary for personal development. It allows employees to stay ahead of the competition by learning new skills and keeping up with technological advances.

Employer responsibilities

[edit | edit source]

Organisations use these strategies to foster mentally healthy workplaces and train employees. Employees are taught to be resilient and not give up when things get tough. Some of the approaches are:

Staff training

[edit | edit source]All employees should go through mental health training. For example, Mental health first aid training, can be provided to employees, giving them the tools they need to help themselves and their coworkers. It will also help reduce the stigma against mental health by changing norms (see Figure 3).

According to Dimoff and Kelloway (2019), employees who get mental health training are better[clarification needed] than their coworkers. They can recognise mental health problems and help others to address them. Managers and staff trained in mental health can notice problems and provide early support to address the issue.

Ergonomics and workplace design

[edit | edit source]Ergonomics and the design of the workplace improves the mental health of the workforce. Poor workstation design can cause physical and psychological stress. This can lower the quality of work and expose employees to awkward positions. Studies have shown that long-term stress can make it harder for people to think and do their jobs well (Faez et al., 2021).

Studies have shown that workplace setup affects mental health and how people feel about themselves. Research shows that the air quality and lighting at work greatly impact how much work gets done (Al horr et al., 2016). Another study found that exposure to sunlight and spending time outside improved organisational commitment and job satisfaction. Regular breaks were also suggested to reduce depression and anxiety (An et al., 2016). Changes to the physical environment can help physical and mental health.

Ongoing support

[edit | edit source]Ongoing support is essential for recovery and rehabilitation. For someone suffering from a mental illness such as anxiety or depression, the workplace can be critical to their recovery. A person's recovery can be affected by a helpful manager who knows proactive and reactive ways to help. Support from the manager and the company can decide how soon someone gets better, whether they keep their job or leave the company (see Figure 4).

Managers who received training in mental health were more likely to discuss mental health issues with their colleagues (Dimoff & Kelloway 2019). They also suggest available support to resolve the issues. According to Kawakami et al. (2005), web-based WMHT for supervisors increased employee friendliness and autonomy in Japanese organisations.

Incentives

[edit | edit source]Employers can incentivise participation in physical and mental health care activities. Participation in self-care activities can be either subsidised or offered on-site. Employers can also recognise and reward employees for participating and maintaining healthy behaviour.

Cultural competency

[edit | edit source]Culture affects how people think about health and illness, seek treatment, and find ways to deal with problems (Dune et al., 2018). Managers and supervisors must be able to help their employees in a dynamic and diverse work environment. Cultural competence will help all employees, regardless of their beliefs and values. It will allow an inclusive and healthy workplace.

Simon, Alex's boss, noticed that he was behaving differently and set up a meeting with him. Simon gave Alex unconditional positive regard and empathy. He had gone through a mental health first-aid and workplace mental health program. Simon was a supportive and proactive manager. He offered flexible work options to Alex and informed him about the company's well-being program. Alex was able to work in a healthy environment because he had a trained and caring manager. The company also helped him get in touch with a counsellor, which helped him to get better. |

Psychological theories and their influence on WMHT

[edit | edit source]Many psychological theory are used to understand and address WMHT. Several mini-theories are frequently integrated to design a programme and develop the training module. Two examples are:

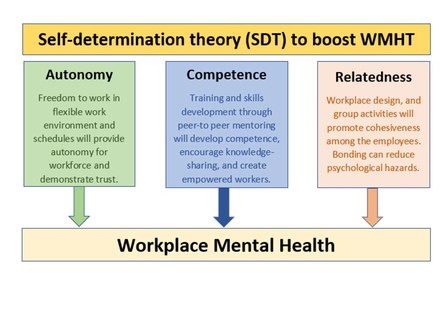

Self-determination theory to boost WMHT

[edit | edit source]

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a theory of motivation that explains how people may be motivated to achieve their goals. Deci and Ryan (1985) say that three main and universal psychological factors help people grow and change. These are perceived competence, relatedness, and autonomy.

For personal growth or behaviour change, people need to become good at tasks and learn new skills (competence). They also need to feel like they belong and are connected to others (relatedness) and in charge of their actions and goals (autonomy) (see Figure 5).

Employers can assist with:

- The ability to work from home or flexible hours can show that the employer trusts the employee while giving them freedom.

- Training and upskilling employees to do their jobs efficiently.

- Intergroup and interpersonal relationships can help employees develop a healthy mental environment at work. Social support can lessen the effects of stress and depression.

Gagné and Deci (2005) found that giving people more freedom can boost motivation and performance. It directly affects an organisation's bottom line. Flexible working conditions may not be right for every job or employee. The goal is to give employees the power to choose from real options that meet both the needs of the organisation and the needs of the people who work there.

Positive psychology interventions for WMHT

[edit | edit source]Positive psychology advocates for a proactive approach. Employees can cope with the negative effects of stressful situations by developing resilience skills (Donaldson et al., 2019). According to Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), individuals have inner resilience, strengths, and the ability to achieve optimal functioning. Employee resilience and mental toughness training can boost an individual’s resilience, resulting in positive transformation (Donaldson et al., 2019). Positive psychology focuses on core concepts such as strengths, values, and self-compassion. It can be used to improve any organisation by using the following interventions (Donaldson et al., 2019):

- Nurturing high-performance teams at workplaces through group goals, mutual trust and respect, open communication and constructive feedback.

- Encouraging strengths through upskilling and aligning roles based on individual strengths.

- Developing employee resilience through training such as Penn Resiliency Program (PRP) and Master Resilience Training (MRT).

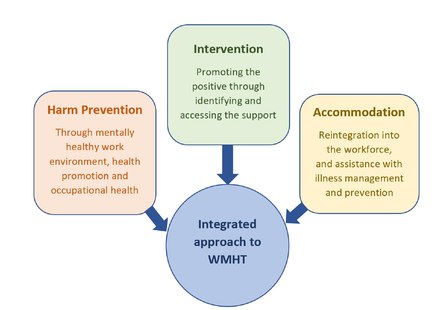

Integrated approach

[edit | edit source]

Based on several psychological theories and intervention strategies, Kelloway (2017) identified three pillars for improving mental health in the workplace (see Figure 6).

Prevention

[edit | edit source]According to Kelloway (2017), employers and supervisors should evaluate their management style. Their approach should not negatively impact employees' mental well-being. Actions of unfair or hostile managers and supervisors harm employees' performance and self-esteem. Supportive managers can improve their employees' mental health by reducing risk factors.

Intervention

[edit | edit source]Not all life stressors result from workplace conditions; personal lives may bleed into work. The manager or supervisor must address mental health problems among employees regardless of the cause. They can act as resource facilitators by assisting the struggling employees with:

- recognising if any additional help is required

- identity the available supports and resources, and

- guiding how to access the resources.

Accommodation

[edit | edit source]Kelloway (2017) identified two most significant challenges for workers with mental health issues:

- reintegrating and accommodating employees after an absence, and

- identifying and addressing the reasons to retake mental health leave.

Employers can address this issue through workplace wellness programs and equity, diversity, and inclusion policies.

Current WMHT techniques employed at workplaces

[edit | edit source]WMHT works by strengthening protective factors and reducing risk factors in the workplace. Lamontagne et al. (2014) suggested three levels of strategy to achieve this:

- The first level of the intervention is proactive, and the goal is to prevent people from harm. Reducing or managing physical and mental health risks helps achieve this.

- The second intervention level is management, when employees have mental health problems. WMHT training, which aims to teach staff members ways to be resilient and cope, helps to achieve this.

- The third level of intervention is a reactive one that tries to reduce the impact of illness on daily life.

By establishing healthy work environments, workplaces concentrate on the proactive phase. Employers must realise that continuous exposure to psychological hazards heightens the likelihood of long-term illnesses. Intervention plans must be in place to help at all levels.

The most widely used WMHT techniques are:

- Resilience training

- Mindfulness training

- Continuous professional development

- Stress inoculation training

- Physical exercise programs

- Improved working conditions

- Flexible working schedules

- Multicomponent intervention

Impact of WMHT techniques

[edit | edit source]WHMT is marketed as a one-size-fits-all solution. Despite its moderate success, it does not support every employee. The organisations have not made training accessible for everyone. WMHT has helped to reduce employee stigma. Employees have started discussing mental health issues. Still more needs to be done. Along with a positive and healthy work environment, training in mental health and resilience has increased productivity and reduced absenteeism (McDaid et al., 2019). Through meditation awareness training, Shonin et al. (2014) found significant improvements in work-related stress, job satisfaction, psychological distress, and employer-rated job performance.

Future

[edit | edit source]Positive psychology programs could be the future of WMHT. The Penn resiliency program takes a proactive approach based on positive psychology. It yielded excellent results. The application of master resilience training developed by The United States Army lowered stress, anxiety, and depression in participants from various professions. It focuses on emotional, cognitive, mental, physical, and spiritual resilience. The intervention of these two training programs boosted the performance of Australian Football League players (Steinfort, 2015). A virtual reality headset is another futuristic method. Employees can be taught how to cope with stress in a healthy way by training them in a virtual world.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]WHMT trains people to be more resilient and mentally tough in the face of everyday life challenges and complex work environments of modern organisations. To put the stigma to rest, everyone suffers from mental health issues. Addressing stigma has allowed more employees to open up and discuss mental health issues. Though this is a positive move, more needs to be done to accommodate employees with mental health difficulties.

Employees alone are not responsible for mental health concerns. The employers are responsible for supporting work-life balance and addressing work-related mental health issues. A few theories and integrated mini-theories, such as SDT and positive psychology, are used to address WMHT. The primary goal of training is to skill and upskill employees and promote resilience and mental toughness. Even though it's new, positive psychology is becoming an important part of WMHT because it lets employees figure out what works for them to deal with life's stresses.

Future WMHT could consider utilising technology such as VR which can allow participants to learn from experiences in a safe virtual environment. Employee perspectives on mental health are shifting; now is the moment for employers to invest in WMHT to build sustainable workplaces. A sustainable future can include support, empathy, and seamless reintegration of employees into the workforce without bias. WHMT has the potential to contribute to the creation of a mentally and physically healthy society of the future.

Take home message

| Most mental health sufferers can lead fulfilling lives if mental illness stigma is removed. Mental health should be treated like any other illness. Achieving this goal can be aided by workplace mental health training. Participate in WMHT. It is possible. It is attainable.

|

See also

[edit | edit source]- Mental toughness (Book chapter, 2021)

- Mindfulness

- Negative emotions in the workplace (Book chapter, 2018)

- PERMA model of well-being (Book chapter, 2020)

- Workplace mental health (Book chapter, 2020)

References

[edit | edit source]An, M., Colarelli, S. M., O'Brien, K., & Boyajian, M. E.. (2016). Why we need more nature at work: Effects of natural elements and sunlight on employee mental health and work attitudes. PLOS ONE, 11(5), e0155614. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155614

Barnett, Baker, E. K., Elman, N. S., & Schoener, G. R. (2007). In pursuit of wellness: The self-care imperative. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 38(6), 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.603

Chopra, P.. (2009). Mental health and the workplace: issues for developing countries. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 3(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-3-4

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109-134. https://10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Dimoff, J. K., & Kelloway, E. K. (2019). With a little help from my boss: The impact of workplace mental health training on leader behaviors and employee resource utilization. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000126

Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., & Donaldson, S. I. (2019). The effectiveness of positive psychology interventions in the workplace: A theory-driven evaluation approach. Theoretical Approaches to Multi-Cultural Positive Psychological Interventions, 115–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20583-6_6

Dune, T., Caputi, P., & Walker, B.. (2018). A systematic review of mental health care workers' constructions about culturally and linguistically diverse people. PLOS ONE, 13(7), e0200662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200662

Faez, E., Zakerian, S. A., Azam, K., Hancock, K., & Rosecrance, J.. (2021). An assessment of ergonomics climate and its association with self-reported pain, organizational performance and employee well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052610

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L.. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Grawitch, Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal, 58(3), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.58.3.129

Kawakami, N., Takao, S., Kobayashi, Y., & Tstsumi, A. (2005). Effects of web-based supervisor training on job stressors and psychological distress among workers: A workplace-based randomized controlled trial. Journal of Occupational Health, 48(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.48.28

Kelloway E. K. (2017). Mental health in the workplace: Towards evidence-based practice. Canadian Psychology = Psychologie Canadienne, 58(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000084

Lamontagne, A. D., Martin, A., Page, K. M., Reavley, N. J., Noblet, A. J., Milner, A. J., Keegel, T., & Smith, P. M.. (2014). Workplace mental health: developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-14-131

Mcdaid, D., Park, A.-L., & Wahlbeck, K.. (2019). The economic case for the prevention of mental illness. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013629

Posluns, K., & Gall, T. L.. (2020). Dear mental health practitioners, take care of yourselves: A literature review on self-care. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 42(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-019-09382-w

Sauter, S., Lim, S., & Murphy, L. (1996). Organizational health: A new paradigm for occupational stress research at NIOSH. Japanese Journal of Occupational Mental Health, 4, 248-254

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.5

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., Dunn, T. J., Singh, N. N., & Griffiths, M. D.. (2014). Meditation awareness training (MAT) for work-related wellbeing and job performance: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12(6), 806–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-014-9513-2

Steinfort, P. J. (2015). Tough teammates: Training grit and optimism together improves performance in professional footballers. Scholarly Commons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mapp_capstone/79/

External links

[edit | edit source]- 5 ways to improve employee mental health (American Psychological Association)

- Economic analysis of workplace mental health promotion and mental disorder prevention programmes and of their potential contribution to EU health, social and economic policy objectives

- Guide to promoting health and wellbeing in the workplace. (ACT Government)

- Mental Health at the Workplace (European network for workplace health promotion)

- Why it’s more important than ever for workplaces to have staff well-being plans (The World Economic Forum)