Motivation and emotion/Book/2022/Help-seeking among boys

What are the barriers and enablers of help-seeking in boys?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Help-seeking is an adaptive coping mechanism whereby people seek external assistance with mental health concerns (Rickwood and Thomas, 2012). A boy is a male child, or more generally, a male of any age (Norvig, 1989). The low prevalence of help-seeking amongst boys is a phenomenon widely recognised for more than two decades (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Clement et al., 2015; Lynch et al., 2018; Tudiver & Talbot, 1999). The barriers to boys' help-seeking are complex and lie within concepts of traditional masculinity, fatherlessness, the modern school environment, peer influence and a loss of purpose. Finding enablers to help-seeking among boys requires a concerted effort to improve social relationships and emotional intelligence and a reframing of help-seeking as a form of taking action. We begin by reflecting on why help-seeking for boys is important.

Many know a young man who is struggling: maybe he's disinterested in school, has emotional disturbances, doesn't socialize much, has few real friends or no female friends, or is a part of a gang; maybe he's addicted to drugs, in prison or highly unmotivated to improve personal circumstances. Perhaps he's a son, friend or relative, or you can even see yourself represented in Figure 1. Can boys really be in a crisis, or is it just that women's circumstances are improving while boys' remains the same? Over the past two decades, rates of boy's suicide (ABS, 2021; CDC, 2022), excessive pornography use (Kor et al., 2014), video gaming addiction (Brandt, 2008; Young, 2009), perpetration of domestic violence (AIHW, 2022; Office of National Statistics, 2020), delinquent behaviour (Breslow, 2014; Sampson & Laub, 2017) engagement with terrorism (AFP, 2022; Kangarlou, 2015; Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020), alcohol and drug use (AIWH, 2021; Britton et al., 2015), fatherlessness (Corneau, 2018; Farrell, 2018) and academic failure (Beyens et al., 2014; Gurian, 2010) have all increased. Globally, these issues affect both sexes and place significant costs on families, institutions and governments.

Domestic violence against women and their children costs billions of dollars (KPMG, 2016). Moreover, acts of terrorism including school shootings involve a high number of boys with absent fathers (Farrell, 2018; Kangarlou, 2015; Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020). Help-seeking for boys is important for both practical and theoretical reasons: as previously alluded to, whenever only one sex wins, both sexes lose. We are all driven by an internal process that gives our behaviour energy, direction, and persistence. Our needs, cognitions and emotions play an important role in our development (Reeve, 2018), and so if these processes disrupted, we must understand why. While many of the problems face by boys that boys, such as excessive pornography use and academic failure constitute reasons for requiring help, they do not necessarily represent barriers - the two are often confused.

|

Focus questions:

|

Barriers to help-seeking

[edit | edit source]

The soldier mentality

[edit | edit source]

The soldier mentality can be described as "pushing on in spite of suffering" because displaying emotions confers weakness. Soldiers enjoy a reputation of significant strength and mental toughness, characteristics that inspire (see Figure 2). Yearly commemorations reinforce that a man's death for country and the greater good is heroic. However, the environment is changing and boys are in a transition phase whereby old rules still apply (Zimbardo, 2015). Before and during the early 20th century, boys were often brought up with the purpose to serve - whether it was his family (father), community (worker) or country (soldier). For some, this involved menial tasks such as mowing the learn or fixing the car; for others, this purpose was fulfilled by joining the army. Responsibility helped boys develop autonomy and competency, and prepared them for raising children and establishing himself into the community (Thompson & Pleck, 1986).

Today, western societies often inculcate boys that they must serve by being responsible and proactive citizens who contribute to their community. Simultaneously, boys are often criticised for being 'too traditional' (Ahmed, 2022). This manifests as boys finding difficulty understanding the modern, more nuanced form of masculinity. For example, masculine dispositions such as competition or aggression are contemporarily labelled as symptomatic of 'toxic masculinity', as evidenced by Zimbardo (2015) who found that 63% of young male respondents believed that conflicting messages regarding masculinity from media and other institutions constituted a major contributor to struggles with motivation. Furthermore, The Men's Project & Flood (2018) found that 69% of young males believed that society endorsed males acting strong even if scared, despite only 47% of respondents personally endorsing such a belief. Thus, prejudicial attitudes of traditional masculinity can confer a barrier to help seeking: pre-conceived social structures, known as stigmas, can result in boys feeling as though their inherent dispositions suddenly represent deviant behaviour, which they would rather hide than treat.

For many boys, help-seeking is synonymous with a loss of control as a result of disclosing personal information (Vogel & Wester, 2003). Additionally, dependence on others and feelings of incompetency (Chan, 2013; Rickwood et al., 2007) confer additional barriers to help-seeking, fostered by stigmas that demonstrate a social identity which devalue their group within certain social contexts (Crocker et al., 1998), thereby reinforcing embarrassment, fear and shame for being a male (Hernan et al., 2010; Lynch et al., 2016). These barriers suggest that restrictive emotionality, a factor contained within the Male Role Norms Inventory—Revised (MRNI–R) (Levant et al., 2010), may play a role in helping boys maintain their toughness and preserving traditional masculine ideals. Mixed messaging about what it means to seek help is then complicated further without the appropriate male role models to show boys what expressing their emotions looks like.

Fatherlessness

[edit | edit source]The central theory of the life course, first proposed by Erikson (1950), posits that adolescence occurs before young adulthood - a period between late teens and the age of about 40. Historically, it was at the beginning of young adulthood that people married, but this time of life is now characterised by job changes and aspirations for post-secondary education, as the median age to marry increases. Simultaneously, premarital sex and cohabitation is more accepted by society and many view marriage as restrictive (Arnett, 2007), yet research shows that cohabiting couples are much more likely to break up and four times more likely to be unfaithful (Kaczor, 2022). Unfortunately, fathers spend far less time with their sons in recent years and thus struggle to provide support and guidance or aid in the development of intrinsic motivation - the act of participating in an activity to fulfil an internal desire for pleasure (Vallerand et al., 1992). The problem now is that, unlike the 20th century, fathers are with their sons much less and cannot provide them with this support or guidance.

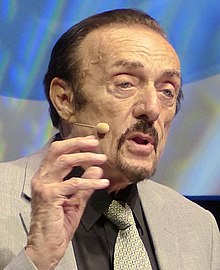

Indeed, record numbers of boys are growing up without a father figure (see Figure 3). The Australian Bureau of Statistics concludes that 15% of Australian households (more than 1 million) are single parent families, 80% of which are single mothers. Similarly, in the United States, 18.4 million children, or 1 in 4, live without a biological, step, or adoptive father at home (National Fatherhood Initiative, 2021). In 2019, the U.S. had the world’s highest rate of children living in single-parent households (Kramer, 2019). Single mothers in the UK account for approximately a quarter of families with dependent children, triple the 1971 figure (O'Grady, 2013). With such high percentages of children with single mothers, who exactly is nurturing these young, new mothers who raise these children? Psychologist Philip Zimbardo (2015) believes that fatherless boys in turn are less interested in long-term fatherhood (see Figure 4), noting that long-term relationships are now viewed as a loss of autonomy rather than a gain, and that they constitute a sacrificing of goals for something that is destined to end.

Father involvement is at least five times more important in preventing drug use than parent attachment, rules and trust, as well as strictness, a child's gender, ethnicity or social class (Pruett, 1989). Bryan Rodger of the Australian National University says that Australian studies with large samples have shown parental divorce to be a risk factor for several social and psychological problems in adolescence. These include poor academic achievement, low self-esteem, psychological distress, substance use and abuse, sexual precocity, adult criminal offending, depression, and suicidal behaviour (Rodgers, 1995). When boys suffer because of fatherlessness or a positive male role model in their lives, they might start to look for a male identity somewhere else such as in drugs and alcohol or among gangs.

Social cognitive theory suggests that an individual's knowledge can be acquired through observations of a model, to inform their future behaviours and its consequences (Bandura, 1986). In terms of fatherlessness, those without such a role model find it more difficult to trust and rely on others, and so help-seeking is more challenging (Zimbardo, 2015).

The modern school environment

[edit | edit source]Across the world, reading and writing skills are the best predictors of success (OECD, 2011). These are, however, the two areas where boys are failing the most. Results from the 2021 Australian National Assessment Program - Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) show that one in five teenage boys are semi-literate during high school, with boys twice as likely as girls to struggle with reading and writing at the age of 15 (Plibersek, 2021). School failure and dropout among boys is also more common, with boys being expelled from school three times as often as girls from an early age (Tyre, 2008). Failure and poor educational outcomes early in life means they are not are choosing to pursue high education, with many opting out of the workforce. In fact, of the 42 universities in Australia, 35 have more female than male students with two having more than 70% females in 2016 (Larkins, 2019). The data shows that men with no post-school qualifications are less likely to marry at every age (Heard & Dharmalingam, 2011) and this changes the way that some boys perceive their own futures because they see what is happening to the men around them.

In Australia in 2019, 71.7 per cent of teachers were females and only 28.3 per cent were males. Compared to 50 years ago, 58.7 per cent of teachers were female while 41.3 per cent were male (ABS, 2020). This is also a common trend in other western societies, such as the United States, Europe, and New Zealand (UNESCO, 2015). The lack of male teachers only exacerbates the aforementioned of fatherlessness and lack of people with whom boys can discuss mental health (Zimbardo, 2015).

Consequently, boys in this situation fail to develop mental health literacy, that is knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which support them to recognise risk factors, to manage or prevent mental health problems or acquire information (Jorm et al., 1997). Consequently, boys may implement maladaptive coping mechanisms for emotional and physical pain (Brooks, 2001; Oliffe et al., 2012), such as the use of alcohol and drugs and aggressive behavior (Lynch et al., 2016). This is especially problematic for boys who are members of groups that encourage excessive self-reliance and discourage display of emotions (Biddle et al., 2007; Cleary, 2012).

Negative social influence

[edit | edit source]Given that many boys lack the resources in order to help them seek help, some rely on those around them to provide them with emotional support. Research from Australia on young men suggests that 35% of boys rely on their romantic partner for support if feeling sad depressed. Seeking help from their mother was the next at 34%, while a male friend was the choice for approximately 31% (The Men's Project & Flood, 2018). Research suggests that previous negative experiences towards help-seeking may also be a barrier that prevents young boys from seeking help (Rickwood et sl., 2007). A negative experience may present itself if boys are pressured to conform to the group norms whereby those around them may place less of an emphasis on seeking help. Social Identity Theory would suggest that a young man’s self-concept is important for maintaining his perceived membership of a social group, which could be an important part of establishing pride and self-esteem, as well as a positive self-image (Lynch et al., 2016). Studies have suggested that young men often require a greater level of confidentiality (Gonzalez et al., 2005; Oliver et al., 2005), which may be provided to them by group norms of non-disclosure. From this perspective, young boys may find it more difficult to discuss their mental health with their peers as breaking group norms may suggest vulnerability and thus differentiation from the group. Furthermore, explaining one's position in a group from an "us" perspective, rather than an "I" perspective may make finding support more challenging because personal choices are sacrificed in an effort to conform to male group norms. Young boys may also learn from their peer group that help-seeking is a sign of weakness.

By being vulnerable, many could fear that help-seeking could result in rejection and being ridiculed (Lynch et al., 2016). This may also facilitate the development of self-stigma, which relates to the fear that by seeking help or using therapy, a person will reduce their self-regard, lose confidence in themselves, and that their overall value as boys will diminish (Vogel et al., 2006). This presents a difficult situation for young men, as many adolescents experience identity crises while also desiring the need to belong. It also appears that suicides increase as the pressures of the male role and hormones, such as testosterone, increase. Before puberty, the suicide rates among males and females are about equal in the US. However, between fifteen and nineteen, boys commit suicide at four times the rate of girls, and at the rate of five to six times that of females between twenty and twenty-four (Farrell, 2018). Additionally, Australia, 75% of suicides are male (ABS, 2021). This suggests that suicide is an important sign of an inability to seek help.

A purpose void

[edit | edit source]It is well documented that gaming and other online activities stimulate dopaminergic pathways (Chen et al., 2018; see Figure 5), which may entice boys to isolate themselves in a 'safe space' in which purpose can be explored free of rejection (Zimbardo, 2015) and they can engage in escapism and distraction. Some feel that is a right to refrain from work or completing chores and thus view this misconstrued independence as an accomplishment (Zimbardo, 2015). When an individual is neither intrinsically nor extrinsically motivated, they are said to be amotivated. Such individuals perceive their behaviours as controlled by outside forces when shrouded by fears of incompetence (Vallerand et al., 1992). Problems with interpreting and communicating distress can result in young boys getting stuck in a cycle of avoidance (Biddle et al., 2007). Accordingly, some lack a deficiency-oriented motive to avoid social deprivation, which could be argued is a form of learned helplessness whereby the boy feels powerless to control his circumstances and so becomes a slave to his desire for isolation. This learned helplessness due to amotivation represents a significant barrier to help-seeking behaviour.

Enablers of help-seeking

[edit | edit source]

Mentoring

[edit | edit source]Providing young men with mentors can be an important way to help fill the wisdom gap created by fatherlessness and a lack of positive role models. Mentoring creates space for the boy to believe in himself - it allows 'dreaming big' so the boy can continue to try until he experiences success (Bancroft, 2018). By connecting with older men through families, schools and workplaces, young men can access advice and rely on another for support, particularly during the raft of changes experience during adolescence. Maggie Dent, author of From Boys to Men, says mentors can be seen as a lighthouse: something that is strong and reliable and shines a light towards a safe passage, helping boys to navigate uncertain waters (Dent, 2020). This can help steer the conversation from what young boys are doing wrong, instead focusing on the potential that they have.

The positive youth development (PYD) perspective provides a framework in which mentors can support young boys. The PYD focuses on a group of attributes, also called The Five C's (Lerner, 2009), which have been associated with positive outcomes in youth development programs (Lerner, 2011). The Five C's are:

| Definitions of the Five C's of Positive Youth Development (adapted from DuBois & Karcher, 2013). | |

|---|---|

| "C" | Definition |

| Competence | A positive view of a boy's own actions in certain domains of his life, including social, academic, cognitive, health and vocational |

| Confidence | Providing a boys with an internal sense of positive self-worth and self-efficacy. |

| Connection | Positive bonds among other people and institutions that reflect in exchanges between a boys and his peers, family, school, and community in which there is a mutual effort for maintaining the relationship. |

| Character | Building a boy's understanding of societal and cultural norms, keeping of standards for appropriate behaviours, a sense of morality and integrity. |

| Caring/Compassion | A sense of sympathy and empathy for others where he may express the ability imagine one's self in another's place. |

Family dinners

[edit | edit source]Boys who experience frequent family dinners are generally less likely to engage in drug and alcohol consumption and other risky behaviours (Skeer & Ballard, 2013). Furthermore, in a study on 26,069 adolescents (11 to 15 years-old), frequency of family dinners was positively correlated with the easing of parent–adolescent communication and improved emotional well-being, prosocial behavior, and life satisfaction (Elgar et al., 2013). Family social support is an important part of enabling help-seeking among black African American boys (Lindsey et al., 2010) and American political scientist, activist, and author, Warren Farrell argues that family dinner nights (FDN) allows boys to experience emotional safety so he can express himself (Farrell, 2018). He provides a blueprint that families can use to encourage help-seeking:

- Timing - FDNs should occur every night, but twice a week is minimal. Each dinner should last between an hour and ninety minutes.

- No electronics or TV - If technology is brought out during dinner, they should be taken away for the rest of the evening.

- Rotation of moderator - Each FDN there is a moderator who decides to choses the topic for the dinner. This can range from school life and friendships to family plans and sports.

- Check-ins and discussions about taboos - Before discussing the nights topic, the moderator must check in with each family member for at least three minutes and ask them how they are doing. If someone has a problem, it takes priority.

- Everyone' story and no one's judgment - Each person comes with their own perspective. Each person should listen respectfully and hear what others have to say (Farrell, 2018).

De-stigmatisation

[edit | edit source]Peer group social norms about help-seeking and reciprocity among young male are effective enablers of help-seeking (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Mahalik et al., 2007). The Australian National Rugby League has previously pursued the de-stigmatization mental health by providing a new perspective on help-seeking using professional athletes. For example, the Canberra Raiders have partnered with MensLink, a counselling and mentoring service provided to young boys who may be going through hard times, and have launched a "Silence is Deadly" campaign to encourage young boys to seek help. Given that many boys fear seeking support due to of stereotypes and stigmas (Gulliver et al., 2010), these campaigns temper stereotypes and help portray help-seeking behaviour as socially acceptable. Indeed, Beyond Blue Australia suggests a tailored approach is needed involving this kind of de-stigmatisation. They do this by reframing the stigmas as shown below:

| De-stigmatising help-seeking behaviour among boys (adapted from Beyond Blue, 2014) | |

|---|---|

| Current Frame | New Frame |

| I can handle by mental health problems | No-one is bulletproof |

| Depression and anxiety only happen to weak people | "x" amount of people will experience depression and anxiety in their lifetime |

| Help-seeking is a sign of failure and weakness | Taking actions means you're taking control, protecting yourself is protecting others |

| Help-seeking is only needed when something goes wrong | Early action is the best |

| Drugs are the only way to treat mental illness | There are many treatments available and treatments can be tailored to you |

Building emotional intelligence

[edit | edit source]Research suggests that low emotional intelligence may reduce the likelihood of help-seeking (Ciarrochi et al., 2003) and so building emotional intelligence and mental health literacy can remove this barrier. Teaching boys how to tame rather than suppress emotions, when to express themselves, how to be assertive but not angry and how to listen to others helps to equip them with the necessary tools to self-regulate and seek help if required (Farrell, 2018). Rickwood and Colleagues (2005) formulated a model positing that help-seeking begins first and foremost with the individual's developing an awareness of the problem and then expressing the problem and a need for help to others. This is obviously difficult to achieve for people who lack awareness of their own emotions. Similarly, the health belief model (HBM) also consists of dimensions which explain how an individual views their health and begins with the individual’s perception on the extent to which they may or may not be susceptible to a particular condition or illness (O'Connor et al., 2014). This idea could be utilised by schools to better educate boys regarding mental health and emotion regulation.

Establishing boy mental health communities

[edit | edit source]Research has demonstrated positive outcomes associated with communities of men coming together in spirit of supporting one another. Enabling help-seeking through social connection may play an important role in allowing boys to connect, communicate and confess problems they may find hard to express in other mediums. Some have suggested the utilisation of chat forums, apps and targeted marketing (Beyond Blue, 2014), while others have provided offline interventions such as activity, exercise and sports interventions (Dowell et al., 2021). This also allows boys to learn of ways to support their friends and those around them. By doing this, young boys can re-build a culture of help-seeking that encourages discussion and ways of addressing mental health.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The barriers to help-seeking for boys lie in an historical context where the traditional male role is being transformed and changes in a boy's social relationships have shown to play an important role in their mental health. The metaphor of a soldier mentality reveals underlying barriers to help-seeking that involve the maintenance of traditional male norms in the absence of solutions towards more progressive masculine ideals. Fatherlessness has played a significant negative role in boys socialisation and access to advice and a positive role model and consequently boys willingness to seek help or understanding of mental health challenges. The problem of fatherlessness is exacerbated by the lack of male teachers in schools and a schooling system that sees boys falling behind, perpetuating feelings of inadequacy and failure. Consequently, many boys seek an isolated environment and choose not to partake in work or higher education, or to seek fulfilling relationships. In order to enable help-seeking behaviour, boys need to be instilled with purpose and meaning, which can be achieved through initiatives such as mentoring or even well-run family dinners. Education through de-stigmatisation of mental health concerns through organisations such as Menslink and Beyond Blue and allies such as the National Rugby League as well as teaching boys emotional intelligence further promote help-seeking behaviour and allow boys to help each other. The addressing of barriers and promotion of enablers allows us to progress from the traditional, stereotype soldier whose bravery is demonstrated through suppression of pain to a young man who knows when help is required and recognises the associated benefits.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Boredom and technology addiction (Book chapter, 2020)

- Coping and emotion (Book chapter, 2020)

- Guilt and shame (Book chapter, 2018)

- Jordan Peterson (Wikipedia)

- Mental health help-seeking motivation (Book chapter, 2016)

- Overcoming social stigmas (Book chapter, 2016)

- Sexting motivation (Book chapter, 2018)

- Warren Farrell (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.5.

Ahmed, T. (2020, April 5). Self-Reliance, Youth, And the Task of Character. Institute of Public Affairs. Retrieved October 16, 2022, from IPA. https://ipa.org.au/publications-ipa/research-papers/self-reliance-youth-and-the-task-of-character.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021, October 12). Labor force status of families. Retrieved 15 October, 2022, from ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-status-families/latest-release#:~:text=1.1%20million%20(15.0%25)%20were,age%20siblings)%20(Table%201.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021, September 29). Causes of Death, Australia. Retrieved October 11, from ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/2020#intentional-self-harm-deaths-suicide-in-australia.

Australian Federal Police. (2022, October 16). Extremist recruitment reaching young Australian gamers. Retrieved October 15, 2022, from AFP. https://www.afp.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/extremist-recruitment-reaching-young-australian-gamers.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022, June 30). Australia's youth: Alcohol, tobacco and other drugs. Retrieved October 16, 2022, from AIWH. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/alcohol-tobacco-and-other-drugs.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022, June 30). Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia. Retrieved October 15, from AIWH. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-data/contents/about.

Australian War Memorial. (2021, January 6). Boy Soldiers. Retrieved October 16, 2022, from AWM. https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/boysoldiers.

Bancroft, J., Bashir, M., McMullen, J., Peppercorn, D., Kirby-Parsons, D., Bancroft, B., Manning, N., Isemonger, G., Miller, R., Hutchison, A., Abbatangelo, B., Trindorfer, J., Paul, V., Stone, Y., Caldwell, H., Raj, S., & Mashiloane, K. (2018). Mentoring: The key to a fairer world. Hardie Grant Books: Melbourne.

Bandura, A., & National Inst of Mental Health. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Beyens, I., Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Early adolescent boys’ exposure to Internet pornography: Relationships to pubertal timing, sensation seeking, and academic performance. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(8), 1045-1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614548069.

Beyond Blue (2014). Men’s Help Seeking Behaviour. Hall & Partners. http://manup.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Mens-Help-Seeking-Behaviour.pdf.

Biddle, L., Donovan, J., Sharp, D., & Gunnell, D. (2007). Explaining non-help-seeking amongst young adults with mental distress: A dynamic interpretive model of illness behaviour. Sociology of Health & Illness, 29(7), 983–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01030.x.

Brandt, M. (2008, February 4). Video games activate reward regions of brain in men more than women, Stanford study finds. Retrieved October 15, from Stanford Medicine. https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2008/02/video-games-activate-reward-regions-of-brain-in-men-more-than-women-stanford-study-finds.html.

Breslow, J. (2014, May 1). New Report Slams “Unprecedented” Growth in US Prisons. Retrieved October 13, from Frontline. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/new-report-slams-unprecedented-growth-in-us-prisons/.

Britton, A., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Benzeval, M., Kuh, D., & Bell, S. (2015). Life course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC medicine, 13(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0273-z.

Brooks, G. R. (2001). Masculinity and men's mental health. Journal of American College Health, 49(6), 285-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480109596315.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, July 25). Facts about Suicide. Retrieved October 14, from CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html.

Chan, M. E. (2013). Antecedents of instrumental interpersonal help‐seeking: An integrative review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 62(4), 571–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00496.x

Chen, K. H., Oliffe, J. L., & Kelly, M. T. (2018). Internet gaming disorder: an emergent health issue for men. American journal of men's health, 12(4), 1151-1159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318766950.

Ciarrochi, J., Wilson, C. J., Deane, F. P., & Rickwood, D. (2003). Do difficulties with emotions inhibit help-seeking in adolescence? The role of age and emotional competence in predicting help-seeking intentions. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 16(2), 103-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951507031000152632.

Cleary, A. (2012). Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 498–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.002

Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., Morgan, C., Rüsch, N., Brown, J. S. L., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129.

Corneau, G. (2018). Absent fathers, lost sons: The search for masculine identity. Shambhala Publications.

Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96(4), 608–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.608.

Dent, M. (2020). From boys to men: guiding our teen boys to grow into happy, healthy men. Pan MacMillan: Australia.

Dowell, T. L., Waters, A. M., Usher, W., Farrell, L. J., Donovan, C. L., Modecki, K. L., ... & Hinchey, J. (2021). Tackling mental health in youth sporting programs: a pilot study of a holistic program. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52(1), 15-29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00984-9.

DuBois, D. L., & Karcher, M. J. (Eds.). (2013). ''Handbook of youth mentoring''. Sage Publications.

Elgar, F. J., Craig, W., & Trites, S. J. (2013). Family dinners, communication, and mental health in Canadian adolescents. Journal of adolescent health, 52(4), 433-438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.012.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Growth and crises of the "healthy personality." In M. J. E. Senn (Ed.), Symposium on the healthy personality (pp. 91–146). Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation.

Farrell, W., & Gray, J. (2018). The boy crisis: Why our boys are struggling and what we can do about it. BenBella Books.

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry, 10(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113.

Gurian, M. (2010). The minds of boys: Saving our sons from falling behind in school and life. John Wiley & Sons.

Heard, G., & Dharmalingam, A. (2011). Socioeconomic differences in family formation: Recent Australian trends. New Zealand Population Review, 37, 125-143.

Hernan, A., Philpot, B., Edmonds, A., & Reddy, P. (2010). Healthy minds for country youth: Help‐seeking for depression among rural adolescents. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 18(3), 118-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01136.x .

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). Mental health literacy: a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical journal of Australia, 166(4), 182-186. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x.

Kaczor, C. (2022). The Ethics of Cohabitation. In The Palgrave Handbook of Sexual Ethics (pp. 177-190). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Kangarlou, T. (2015, March 10). Imprisoned IS members open up to Lebanese social workers. Retrieved October 15, from Al-Monitor. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2015/03/terrorism-social-work-jihadist-profile-roumieh-prison.html.

Kor, A., Zilcha-Mano, S., Fogel, Y. A., Mikulincer, M., Reid, R. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). Psychometric development of the problematic pornography use scale. Addictive behaviors, 39(5), 861-868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.027.

KPMG. (2016, May 3). The cost of violence against women and their children in Australia. KPMG.

Kramer, S. (2019, December 12). U.S. has world’s highest rate of children living in single-parent households. Retrieved October 16, 2022, from Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/12/12/u-s-children-more-likely-than-children-in-other-countries-to-live-with-just-one-parent/#:~:text=Almost%20a%20quarter%20of%20U.S.,who%20do%20so%20(7%25).

Larkins, E. (2019). Gender and Citizenship Factors Strongly Influence Discipline Course Choices for Postgraduates at Australian Universities. Retrieved on 17 October, 2022, from University of Melbourne. https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/3764764/gender-disciplines-and-postgraduates.pdf.

Lerner, J. V., Phelps, E., Forman, Y., & Bowers, E. P. (2009). Positive youth development. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Lewin-Bizan, S., Bowers, E. P., Boyd, M. J., Mueller, M. K., ... & Napolitano, C. M. (2011). Positive youth development: Processes, programs, and problematics. Journal of Youth Development, 6(3), 38-62. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2011.174.

Levant, R. F., Hall, R. J., & Rankin, T. J. (2013). Male Role Norms Inventory–Short Form (MRNI-SF): Development, confirmatory factor analytic investigation of structure, and measurement invariance across gender. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031545.

Lindsey, M. A., Joe, S., & Nebbitt, V. (2010). Family matters: The role of mental health stigma and social support on depressive symptoms and subsequent help seeking among African American boys. Journal of Black Psychology, 36(4), 458-482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798409355796.

Lynch, L., Long, M., & Moorhead, A. (2018). Young men, help-seeking, and mental health services: Exploring barriers and solutions. American Journal of Men's Health, 12(1), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315619469.

Mahalik, J. R., Burns, S. M., & Syzdek, M. (2007). Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men's health behaviors. Social science & medicine, 64(11), 2201-2209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035.

National Fatherhood Initiative. (2021). The Statistics Don't Lie: Fathers Matter. Retrieved October 16, 2022, from National Fatherhood Initiative. https://www.fatherhood.org/father-absence-statistic.

Norvig, P. (1989). Marker passing as a weak method for text inferencing. Cognitive science, 13(4), 569-620. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1304_4 .

O'Connor, P. J., Martin, B., Weeks, C. S., & Ong, L. (2014). Factors that influence young people's mental health help‐seeking behaviour: A study based on the Health Belief Model. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(11), 2577–2587. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12423.

O’Grady, S. (2013, March 8). Rise of the Single-parent Family. Retrieved 16 October, 2022, from Express. https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/382706/Rise-of-the-single-parent-family.

OECD. (2011). How do girls compare to boys in mathematics skills? in PISA 2009 at a Glance, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264095250-8-en.

Office of National Statistics. (2020, November 25). Domestic abuse in England and Wales overview: November 2020. Retrieved October 10, from Office of National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwalesoverview/november2020.

Oliffe, J. L., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Bottorff, J. L., Johnson, J. L., & Hoyak, K. (2012). “You feel like you can’t live anymore”: Suicide from the perspectives of Canadian men who experience depression. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 506 -514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.057.

Plibersek, A. (Host). (2021, December 15). Digital Broadcast interview with Alan Jones [Television Broadcast]. In Alan Jones. Sky News. https://www.tanyaplibersek.com/media/transcripts/transcript-tanya-plibersek-digital-broadcast-interview-alan-jones-wednesday-15-december-2021/.

Pruett, K. D. (1989). The nurturing male: A longitudinal study of primary nurturing fathers.

Reeve, J. (2018). Understanding motivation and emotion. John Wiley & Sons.

Richardson, N., Clarke, N., & Fowler, C. (2013). A report on the all-Ireland young men and suicide project. Men’s Health Forum in Ireland.

Rickwood D., Deane F. P., Wilson C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia, 187, 35-39. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x .

Rickwood, D., & Thomas, K. (2012). Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychology research and behavior management, 5, 173-183. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s38707 .

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Australian e-journal for the Advancement of Mental health, 4(3), 218-251. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218.

Rodger, B. (1996). Social and Psychological Wellbeing of Children from Divorced Families: Australian Research Findings. Australian Psychologist, 31(3), 174-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050069608260203.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2017). Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys followed to age 70. In Developmental and life-course criminological theories (pp. 37-74). Routledge.

Skeer, M. R., & Ballard, E. L. (2013). Are family meals as good for youth as we think they are? A review of the literature on family meals as they pertain to adolescent risk prevention. Journal of youth and adolescence, 42(7), 943-963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9963-z.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. D. (2020). ISIS in their own words. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(1), 82-127. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.13.1.1791 .

The Men’s Project & Flood, M. (2018). The Man Box: A Study on Being a Young Man in Australia. Jesuit Social Services: Melbourne.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2015). Education For All 2000-2005: Achievements and Challenges. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2015/education-all-2000-2015-achievements-and-challenges#sthash.7OCMNv7R.dpbs.

Thompson Jr, E. H., & Pleck, J. H. (1986). The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29(5), 531-543. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276486029005003.

Tudiver, F., & Talbot, Y. (1999). Why don't men seek help? Family physicians' perspectives on help-seeking behavior in men. The Journal of Family Practice, 48(1), 47–52.

Tyre, P. (2008). The trouble with boys: A surprising report card on our sons, their problems at school, and what parents and educators must do. Harmony.

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Brière, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The Academic Motivation Scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025.

Vogel, D. L., & Wester, S. R. (2003). To seek help or not to seek help: The risks of self-disclosure. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(3), 351–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.3.351

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Haake, S. (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325.

Young, K. (2009). Understanding online gaming addiction and treatment issues for adolescents. The American journal of family therapy, 37(5), 355-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180902942191.

Zimbardo, P., & Coulombe, N. D. (2015). Man Disconnected: How technology has sabotaged what it means to be male. Random House.

External links

[edit | edit source]- Chance UK (Charity)

- INVISIBLE MEN: engaging more men in social projects by Aman Johal, Anton Shelupanov & Will Norman (The Young Foundation, UK)

- Man (Dis)connected: How The Digital Age is Changing Young Men Forever by Philip Zimbardo (Book).

- Man Up Campaign with Australian Triple M's Gus Worland

- Mentoring: The key to a fairer world by Jack Manning Bancroft (Book)

- Respect: Campaign to stop Violence Against Women (Australian Government)

- Self-Reliance, Youth and the Task of Character by Dr. Tanveer Ahmed (Institute of Public Affairs)

- The Boy Crisis (Website for The Boy Crisis).

- The Boy Crisis: A Sobering look at the State of our Boys | Warren Farrell Ph.D. | TEDxMarin (Youtube).

- The Current Crisis of Masculinity with Ben Shapiro and Jordan Peterson (Youtube)