Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Paedophilic motivation

Why are some people sexually attracted to minors?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Paedophilia is a clinical diagnosis made by a psychologist or psychiatrist and is not a criminal or legal term (Hall & Hall, 2007). Paedophilia is defined as persistent sexual interest in prepubescent children which is indicated by one's sexual urges, thoughts, fantasies, arousal patterns, or behaviour for at least six months.

Paedophilic motivation can be broken down into many categories, namely situational, preferential, non contact and female paedophiles. Some of these have subcategories which are discussed below. More controversial topics such as institutional paedophilia and recidivism rates of paedophilic behaviour is also discussed. Theorists are still researching possible physical and psychological reasoning for paedophilia.

Paedophile typologies

[edit | edit source]

Situational paedophiles

[edit | edit source]The offender's immediate environment affects behaviour and also actively shapes it (Leclerc, Wortley & Dowling, 2016). The immediate environment can, in effect, cause paedophiles to commit offences that were not initially being contemplated at the time. There are four types of precipitators constructed by an environment, specifically, provocations, pressures, prompts and permissions (Wortley, 2001). Firstly, a situational precipitator, such as stressful environment, can cause a paedophile to feel provoked to engage in deviant behaviour. These situational precipitators can provide or sometimes increase the motivation to offend (Leclerc at el., 2016). Second, social affiliations and obligations can cause paedophiles to feel pressured to offend (e.g. peer pressure). Thirdly, paedophiles can be prompted to commit these sexual acts when feelings and thoughts are brought forth by prompts in the immediate environment (e.g. bathing a child). Fourthly, when moral prohibitions have been weakened (e.g. blaming drugs or alcohol for sexual assault), paedophiles can justify their immoral and deviant behaviour as being “permitted” (Wortley, 2001). Situational paedophiles have no preferential interest in children but will molest if the opportunity arises when other sexual outlets are unavailable. This offender is also known to target elderly, disabled, or other victims (Miller, 2013).

The regressed paedophile

[edit | edit source]A regressed paedophile engages in sex with adults, but many also trend towards molesting children, frequently females (Cossins, 1999). This motivation is often a response to a threatened ego, such as sexual rejection from a partner, in which the paedophile is likely to regard the child as a “pseudo-adult” confirming the sexual act as morally acceptable to the offender.

The morally indiscriminate paedophile

[edit | edit source]

Morally indiscriminate paedophiles have sexual relations with adults as well as children. Morally indiscriminate paedophiles may coercively or forcefully abuse their child victims in attempts to heighten excitement by controlling victims that the offender views as helpless and vulnerable. Fantasises of bondage is a common trait in this style of offender (Miller, 2013). These paedophiles offend purely for the satisfaction of their sexual urge and victims are frequently strangers (Lanning, 1994). For such offenders the sexual abuse of children is part of a general pattern of abuse in their life. Prentky et al. (1991) found these paedophiles to have a history of antisocial and criminal behaviour, low social competence and poor interpersonal skills.

The sexually indiscriminate paedophile

[edit | edit source]The sexually indiscriminate paedophile has no particular predilection for children. This type of paedophile has an indiscriminate sexual pattern involving a wide variety of common and unusual sexual practices and partners, often including their own children or stepchildren (Miller, 2013). The sole motivation of this paedophile is the accomplishment of the desired sexual act. There is no intent to hurt the victim and any force used does not exceed the force needed to subdue the child (Burgess et al., 1978). The offender views the victim as an object for sexual relief, perceiving the child solely as an outlet for sexual gratification.

The naïve/inadequate paedophile

[edit | edit source]Naïve or inadequate paedophiles tend to suffer from a form of mental disability. This causes the paedophile to be unable to properly comprehend their impulses or sexual acts committed towards their victim as wrong. The offender abuses children because he is regarded as undesirable and strange by others and is therefore unable to obtain sexual relationships through usual social channels (Miller, 2013). Blanchard et al. (1999) found that paedophiles who offended against prepubescent children had lower IQ scores. This is supported by Murrey, Briggs, and Davis (1992) who found that sex offenders with mental disabilities are more likely to commit offences against children than sex offenders without any mental disability.

Preferential paedophiles

[edit | edit source]These paedophiles prefer children to adults as sexual partners.

The seductive paedophile

[edit | edit source]The seductive offender develops a consenting sexual relationship with the victim. This is often done by seducing their victims by courting them with affection, attention and gifts while gradually lowering their victim's sexual inhibitions over an extended period of time. This allows them to gain intimacy with the victim on a personal and sexual level (Canter, Hughes & Kirby, 1998). The sexual activity attempts to provide a more positive affect or ‘giving’ on the part of the offender by using behaviours such as hugging, kissing, fondling and oral sex performed on the victim.

While the victim is being groomed to the offensive behaviour, the offender will attempt to desensitise the victim. This method is often done through non-sexual physical contact such as tickling or playful wrestling can give way to sexual touching while the child is fully clothed. Over time this develops into genital fondling, which later can lead to shared masturbation and oral sex. Throughout this relationship the offender believes that the child enjoys the sexual aspects of the relationship and encourages the victim to keep the relationship secret (Canter et al., 1998).

The fixated paedophile

[edit | edit source]The fixated paedophile is sexuality fixated at a primitive stage of psychosexual development where children are sexually attractive because, psychologically speaking, the paedophile is essentially a child as well, often appearing emotionally immature and socially incompetent (Miller, 2013). This type of offender is not likely to physically harm victims and instead prefers a gradual process of seduction. Physical affection and intimacy with these children is often as important as the actual sex (Canter et al., 1998). This type of offender often abuses children simultaneously. The offender may travel in order to obtain victims and utilise the internet to seek out victims due to this motivation. Fixated offenders mostly abuse strangers or acquaintances.

Sadistic paedophile

[edit | edit source]Sadistic paedophiles are the most violent and dangerous type of paedophile. Much like the adult serial rapist or killer, the paedophile’s erotic gratification is based on the combination of sexual arousal and sadistic aggression. Paedophiles who act on their desires premeditate and ritualise their acts. This often involves stalking and abducting victims. This is often followed by torture, sexual assault and/or mutilation of their victim (Palermo, 2013) . This is when the offender gains maximum pleasure from the fear, pain, and terror of the victims which often results in the child’s death (Miller, 2013). This offender typically moves around to perpetrate their crimes.

Non contact paedophiles

[edit | edit source]

Paedophiles who commit contact sex offences often have more access to children than those who have greater access to the internet who often use child pornography (Stroebel et al., 2019). Online child pornography paedophiles tend to score lower on indicators of antisocial behaviour as they are more likely to have psychological barriers to sexual offending e.g. greater empathy for victims. Studies suggest that offenders who restrict their offending behaviour to online child pornography are different to contact offenders, often showing greater victim empathy and self-control (Elliott, Beech, & Mandeville-Norden, 2009). There is evidence that more than half of child pornography collectors have no known physical contact with children (Seto, Cantor, & Blanchard, 2006).

Female paedophiles

[edit | edit source]The prevalence of female sexual abuse of children is unknown (Strickland, 2008). While the average age of female paedophiles ranges from 26 to 36 years, like most paedophiles, there is a substantial age range for females (Faller, 1995). Currently there is no consensus as to whether male or female children are more vulnerable to sexual abuse by adult women, however there is a slight preference toward female victims at 68% (Grayston & De Luca, 1999; Christensen & Darling, 2019). In general, female sex offenders tend to use less physical force and rely more on seduction or coercion than male offenders. Female paedophiles tend to come from more deprived backgrounds, frequently suffering from extreme emotional, verbal, physical, and sexual abuse within their own families (Nathan & Ward, 2002).

Offences against strangers are rare with the majority of offences being incestuous in nature, often having a maternal or continuing relationship with the victim (Strickland, 2008). When a perpetrator is a biological parent, the offender is over four and a half times more likely to be female. This is supported by a study revealing female paedophiles are more likely to be listed as the victim’s parent (77.8%) than males (31.3%) (Christensen & Darling, 2019). The majority of incestuously abused children are preschool and school aged (Grayston & De Luca, 1999). Female teachers are more likely to commit offences against older students aged 13 or compared to male teachers who are more likely to abuse students aged 12 or under (Ratliff and Watson, 2014). The majority of women who victimise children do so in conjunction with a male perpetrator and less frequently initiate incidents on their own (Grayston & DeLuca, 1999). Active offenders participate directly in the abuse of children (Green & Kaplan, 1994). Passive female offenders, however, may procure victims for their male partner and often witness the sexual abuse and fail to intervene.

Paedophile offences in institutions

[edit | edit source]Organisational sexual assault appears to be relatively prevalent. Organisational abuse is emotional, physical, or sexual abuse perpetrated by an adult on a child in a paid or voluntary work environment (Gallagher, 2000). One efficient way for a paedophile to gain access to victims is through employment that involves children. It has been suggested that some male offenders specifically pursue employment in an institutional context to sexually abuse children (Christensen & Darling, 2019). Sullivan and Beech (2004) conducted a study of 41 male paedophiles who sexually abused children in institutional settings across religious, teaching, and child care settings and found about 90% of paedophiles admitted they were sexually interested in children by age 21 and almost 57% indicated that their motivation to pursue their profession was to gain access to children.

Paedophiles working with children have exhibited similar grooming strategies to intra-familial paedophiles, often using emotional manipulation or their authority to keep their victims from disclosing the abuse (Leclerc et al., 2016). According to the John Jay College of Criminal Justice (2004), in the United States, it is estimated that 4% of the total number of Catholic priests, consisting of over four thousand priests, may have sexually assaulted over 10,000 children during the past 52 years. The majority of these acts consisted of touching and fondling teenage boys. In a nationwide survey across the United States of America, 10% of almost 4.5 million students reported some type of educator sexual misconduct from students aged 13 to 17 years (Shakeshaft, 2004). Gallagher (2000) explored institutional abuse through child protection records throughout English and Welsh authorities and found that the largest occupational group of sexual abusers were teachers (29%). An English and Welsh Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (2017) supported the Gallagher study when the inquiry found that 22% of victims reported sexual abuse by teachers or educational staff, supporting that this is the largest perpetrator group in an organisational setting. The 2017 Australian Royal Commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse also found that 20.4% of victims reported being abused by a teacher in Australia.

Recidivism rates

[edit | edit source]

Recidivism rates for sex offenders are universally lower than any other criminal offenders. There is a recidivism rate of 11% for any type of offence with the most common re-offence being parole violation, which consists of at least half of the re-offences (Vess & Skelton, 2010). High-risk sex offenders often lose their risk of recidivism over time. Hanson and Morton-Bourgon (2004) studied an aggregated sample of 7,740 sex offenders. The 5-year sexual recidivism rate was 22%, but among high-risk sex offenders who did not re-offend in the first 5 years, the re-offence rate dropped to 4.2% after 10 years. After 10 years, the rate of re-offence continued to decrease.

Studies consistently find that the proportion of child pornography offenders who re-offend with a contact sex offence is lower than the rates typically observed for other paedophiles (Seto, Hanson, & Babchishin, 2011). They found approximately 1% of official recidivism rates for contact sexual offences and a 3% recidivism rate for child pornography offences after a follow-up of up to 6 years.

Some studies have reported that certain sexual orientations of paedophiles such as homosexual and paedophiles who target non-related victims, have the highest rate for repeated offending compared to heterosexual offenders (Barbaree, Langton & Peacock, 2006). Incestuous paedophiles generally have the lowest rate of recidivism (Bartosh, Garby, Lewis & Gray, 2003).

|

Paedophile interviews Louis Theroux's documentary A Place for Paedophiles interviews hospitalised paedophiles at Coalinga State Hospital in 2009 |

|

Quiz time!

|

Theories of paedophilia

[edit | edit source]

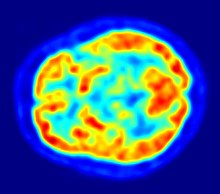

Neuropsychology

[edit | edit source]Paedophiles show pathological personality traits such as anxiousness, inhibited personality, lack of assertiveness and impaired neuro-cognitive functioning (Black, 2000; Cohen et al., 2002). Dennison, Stough, and Birgden (2001) found paedophiles had significantly higher neuroticism and significantly lower extraversion and conscientiousness when compared to non paedophiles. Paedophiles assessed with neuropsychological batteries (e.g., the Halstead-Reitan and Luria-Nebraska Batteries) show greater impairments largely in verbal and visual-spatial abilities than other nonsexual offenders, or those who commit sexual crimes against adults (Langevin, Wortzman, Wright, & Handy, 1989).

When paedophiles are compared with non criminal community control groups or with men convicted of non sexual crimes, convicted paedophiles typically score lower in intelligence and also have lower immediate and delayed memory performance (Blanchard et al., 2007). Cognitive deficits in paedophiles can be seen to be mediated by the prefrontal cortex, which may account for their behavioural disinhibition, disinhibition of automatic motor responses, working memory deficits, and impairment of cognitive flexibility (Joyal, Black, & Dassylva, 2007).

Evolutionary psychology

[edit | edit source]Biological significant stimuli is processed with increased priority to maximise the efficiency of reacting. Before biological stimuli can be perceived consciously, early attentional processes allow for a high level of processing (Compton, 2003). Krupp (2008) suggests that threat stimuli is similar to sexual stimuli. The information processing approach assumes that sexually relevant features of a stimulus are pre-attentively selected and automatically induce focal attention to these sexually relevant aspects. Focal attention on sexually relevant stimulus induces conscious appraisal of these stimulus aspects (Jordan et al.,2016). If stimuli is in accordance with sexual scripts of a explicit memory, the individual classifies the stimulus as sexually relevant. This induces a conscious experience of sexual arousal. When considering the automatic and controlled processing of sexual stimuli, it is understandable that the processing of sexual features which are presented with a cognitive task will likely interfere with the cognitive processing especially when considering evolutionary theory.

|

Evolutionary example When a male decides to settle down and devote himself to his family, he wants to be sure it is, in fact, his family. One way to do this is to choose the youngest females because younger women are more likely to be healthy and less likely to have borne or to be carrying another male's offspring. In as much as virginity guarantees paternity, the younger the girl, the more likely she is to be the exclusive carrier of the prospective husband's genes (Miller, 2013). |

Cognitive model

[edit | edit source]According to conditioning theories of the aetiology of paedophilia, early sexual experiences with other children are a first introduction to interpersonal sexuality. Some studies suggest early sexual behaviour experiences with minors can influence their cognitions concerning children as sexual beings (Houtepen, Sijtsema & Bogaerts, 2016). During these early sexual experiences, individuals become aware of their sexual preferences and the conditioning attraction to particular childlike physical appearances. These characteristics are then never properly adjusted to older individuals (Seto, 2004). Although it is not clear what mechanism underlies this developmental stagnation, conditioning theories suggest that in most paedophiles, the sexual attraction is developed through experience. However, Houtepen et al., (2016) found that some paedophiles did not engage in sexual contact before puberty.

Paedophile offender treatment programs rely on cognitive or behavioural interventions to reduce the risk of recidivism. Cognitive behavioural therapies are intended to change internal processes such as thoughts, beliefs, emotions and physiological arousal, alongside changing overt behaviour, such as social skills or coping behaviour (Ryan, Baerwald & McGlone, 2008). Cognitive distortions are believed to be one of the primary factors in the initiation and maintenance of sexual abusive behaviours. Some paedophiles who rely on interpersonal relationships as a way to manage difficulties and stressors may be more susceptible to impaired functioning of cognitive mediation (Ryan et al., 2008). These individuals will experience distress or impaired judgment when interpersonal interactions are not available or are not fulfilling. Ryan et al. (2008) suggests that many paedophiles show poorer meditational abilities, falling in the mild to pathologically impaired range of functioning.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Paedophiles are either distressed about their sexual urges and experience interpersonal difficulties as a result or act on their urges due to a comfortability in their fantasies (Hall & Hall, 2007). To suggest that people with paedophilia cannot change implies that their sexual interests cannot change, however paedophilic behaviours are not persistent. Early recognition of risk factors and early interventions are crucial in preventing offending. Furthermore, results suggest the risk for offending can be decreased by creating more openness about paedophilia and by providing social support and control to paedophiles (Houtepen et al., 2016).

Paedophilic interest is not illegal but acting on non-consensual interests, including sex with children is. Situational paedophilic offenders are less likely to re-offend when compared to preferential paedophilic offenders. This highlights there are different motivations for sexually assaulting children. Risk assessments are vital to accurately identify important decisions about paedophilic offenders, from sentencing and treatment. Further validation of risk measures could guide treatment planning which could lead to important contributions to the rehabilitation of an offender (Seto & Eke, 2015).

See also

[edit | edit source]- Child sexual exploitation access motivation (Book chapter, 2015)

- Motivation (Wikiversity)

- Paraphilias (Book chapter, 2017)

- Paedophilia (Wikipedia)

- Sex offender motivation (Book chapter, 2010)

- Sexual violence motivation (Book chapter, 2014)

References

[edit | edit source]Bartosh, D. L., Garby, T., Lewis, D., & Gray, S. (2003). Differences in the predictive validity of actuarial risk assessments in relation to sex offender type. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 47(4), 422-438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X03253850

Blanchard, R., Kolla, N. J., Cantor, J. M., Klassen, P. E., Dickey, R., Kuban, M. E., & Blak, T. (2007). IQ, handedness, and pedophilia in adult male patients stratified by referral source. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 19(3), 285–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320701900307

Blanchard, R., Watson, M. S., Choy, A., Dickey, R., Klassen, P., Kuban, M., et al. (1999). Pedophiles: Mental retardation, maternal age, and sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018754004962

Burgess, A. W., Groth, A. N., Holmstrom, L. L. and Sgroi, S. M. (1978). Sexual Assault of Children and Adolescents. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Canter, D., Hughes, D., & Kirby, S. (1998). Paedophilia: Pathology, criminality, or both? The development of a multivariate model of offence behaviour in child sexual abuse. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 9(3), 532-555. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585189808405372

Christensen, L., & Darling, A. (2019). Sexual abuse by educators: a comparison between male and female teachers who sexually abuse students. The Journal of Sexual Aggression, 26(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2019.1616119

Compton, R. J. (2003). The interface between emotion and attention: A review of evidence from psychology and neuroscience. Behavioral and cognitive neuroscience reviews, 2(2), 115-129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582303002002003

Cossins, A. (1999). A Reply to the NSW Royal Commission Inquiry into Paedophilia: Victim Report Studies and Child Sex Offender Profiles — A Bad Match? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 32(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/000486589903200105

Elliott, I., Beech, A., Mandeville-Norden, R., & Hayes, E. (2009). Psychological Profiles of Internet Sexual Offenders: Comparisons With Contact Sexual Offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 21(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063208326929

Faller, K. (1996). A Clinical Sample of Women Who Have Sexually Abused Children. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 4(3), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v04n03_02

Gallagher, B. (2000). The extent and nature of known cases of institutional child sexual abuse. The British Journal of Social Work, 30(6), 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/30.6.795

Grayston, A. D., & De Luca, R. V. (1999). Female perpetrators of child sexual abuse: A review of the clinical and empirical literature. Aggression and violent behavior, 4(1), 93-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00014-7

Green, A. H., & Kaplan, M. S. (1994). Psychiatric impairment and childhood victimization experiences in female child molesters. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(7), 954-961. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199409000-00004

Hanson, R. K. & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: a meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 73(6), 1154. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154

Houtepen, J., Sijtsema, J., & Bogaerts, S. (2016). Being Sexually Attracted to Minors: Sexual Development, Coping With Forbidden Feelings, and Relieving Sexual Arousal in Self-Identified Pedophiles. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 42(1), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1061077

Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. (2017). Victim and survivor voices from the truth project (June 2016-June 2017). Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. https://www.iicsa.org.uk/document/victim-and-survivor-voices-truth-project

Jordan, K., Fromberger, P., von Herder, J., Steinkrauss, H., Nemetschek, R., Witzel, J., & Müller, J. (2016). Impaired Attentional Control in Pedophiles in a Sexual Distractor Task. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, 193–. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00193

Joyal, C., Black, D., & Dassylva, B. (2007). The Neuropsychology and Neurology of Sexual Deviance: A Review and Pilot Study. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 19(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320701900206

Krupp, D. (2008). Through Evolution’s Eyes: Extracting Mate Preferences by Linking Visual Attention to Adaptive Design. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9273-1

Langevin, R., Wortzman, G., Wright, P., & Handy, L. (1989). Studies of brain damage and dysfunction in sex offenders. Annals of Sex Research, 2(2), 163-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00851321

Lanning, K. V. (1994). Child molesters: a behavioural analysis. School Safety, 12-17.

Leclerc, B., Wortley, R., & Dowling, C. (2016). Situational Precipitators and Interactive Forces in Sexual Crime Events Involving Adult Offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 43(11), 1600–1618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816660144

Miller, L. (2013). Sexual offenses against children: Patterns and motives. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 18(5), 506–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.006

Murrey, G. J., Briggs, D., & Davis, C. (1992). Psychopathic disordered, mentally ill, and mentally handicapped sex offenders: a comparative study. Medicine, Science and the law, 32(4), 331-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580249203200408

Nathan, P., & Ward, T. (2002). Female sex offenders: Clinical and demographic features. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 8(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600208413329

Palermo, G. (2013). The Various Faces of Sadism. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 57(4), 399–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X13480125

Prentky, R., Knight, R., Burgess, A., Ressler, R., Campbell, J., & Lanning, K. (1991). Child Molesters Who Abduct. Violence and Victims, 6(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.6.3.213

Ratliff, L., & Watson, J. (2014). A Descriptive Analysis of Public School Educators Arrested for Sex Offenses. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(2), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.870275

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. (2017). Final information update. Australia. https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_information_update.pdf

Ryan, G., Baerwald, J., & McGlone, G. (2008). Cognitive mediational deficits and the role of coping styles in pedophile and ephebophile Roman Catholic clergy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20428

Seto, M. (2004). Pedophilia and Sexual Offenses against Children. Annual Review of Sex Research, 15(1), 321–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.2004.10559823

Seto, M., Cantor, J., & Blanchard, R. (2006). Child Pornography Offenses Are a Valid Diagnostic Indicator of Pedophilia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology (1965), 115(3), 610–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.610

Seto, M. C., & Eke, A. W. (2015). Predicting recidivism among adult male child pornography offenders: Development of the Child Pornography Offender Risk Tool (CPORT). Law and Human Behavior, 39(4), 416–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000128

Seto, M., Hanson, R., & Babchishin, K. (2011). Contact Sexual Offending by Men With Online Sexual Offenses. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(1), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210369013

Shakeshaft, C. (2004). Educator sexual misconduct: A synthesis of existing literature. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Spiering, M., & Everaerd, W. (2007). The sexual unconscious. In Kinsey Institute Conference, 1st, Jul, 2003, Bloomington, IN, US; This work was presented at the aforementioned conference. Indiana University Press.

Stroebel, S., O’Keefe, S., Griffee, K., Harper-Dorton, K., Beard, K., Young, D., Swindell, S., Stroupe, W., Steele, K., Lawhon, M., & Kuo, S. (2019). Effects of the sex of the perpetrator on victims’ subsequent sexual behaviors and adulthood sexual orientations. Cogent Psychology, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1564424

Sullivan, J., & Beech, A. (2004). A comparative study of demographic data relating to intra- and extra-familial child sexual abusers and professional perpetrators. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 10(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600410001667788

Theroux, L. (2009). A Place for Paedophiles [Film].

Vess, J., & Skelton, A. (2010). Sexual and violent recidivism by offender type and actuarial risk: Reoffending rates for rapists, child molesters and mixed-victim offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law. 16(7), 541-554. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802612908

Wortley, R. (2001). A classification of techniques for controlling situational precipitators of crime. Security Journal, 14(4), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.sj.8340098

External links

[edit | edit source]- PedoHelp (pedo.help)