Motivation and emotion/Textbook/Motivation/Paraphilias

| This page is part of the Motivation and emotion textbook. See also: Guidelines. |

Overview

[edit | edit source]- Learning objectives

In this chapter we will discuss:

- What is Paraphilia?

- What is the Diagnostic Criteria for Paraphilia?

- What is the Motivation Behind Paraphilia?

- What are the Treatments for Paraphilia?

Introduction

[edit | edit source]In the development of self-individuation, which takes place in childhood and adolescence, the young person becomes conscious of his or her sexual self and of the differences between themselves and the opposite sex. This is followed by sexual interests that are driven by biological needs and desires. Attraction to the another follows and the individual experiences his or her sexuality. This takes place not only because people are instinctually attracted to one another by desire but also because of a voluntary, purposeful choice to attain a psychosexual union. If you are like most people your sexual interest is towards other physically mature adults (or late adolescents) all of whom are capable of freely offering or withholding their consent. The above is the ‘normal process’ but what if you were sexually attracted to something or somebody other than another adult? For example, an animal such as a dog or horse or shoes? Or what if your only means of obtaining sexual satisfaction is to commit murder? Such patterns of sexual arousal and countless others exist in a large number of individuals. These disorders of sexual arousal are called paraphilias. Paraphilia is generally fetish-based in that both arousal and gratification is dependent on very specific objects, body parts and acts. It is when this fetish becomes the only method in which the person can find arousal and gratification that it becomes paraphilia. This chapter will focus specifically on the motivations behind paraphilia using theoretical models and evidence based research. The existing theories discussing the motivations behind paraphilia are biological explanations, psychoanalytic explanations and cognitive-behavioural and learning explanations.

Definition, Prevalence and Incidence

[edit | edit source]Definition

[edit | edit source]Definition:

|

Paraphilias has been recognised as a mental disorder since 1905. The definition of paraphilia is derived from the Greek “Para” (deviation) and “Philia” (attraction) (Seligman & Hardenburg, 2000). |

DSM IV: According to the revised fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), to diagnose a paraphilia, the patient must have recurring, intensely arousing fantasies, sexual urges or behaviors that involve nonhuman objects; that involve the suffering or humiliation of oneself, one's partner, children, or non-consenting others; and that occur over a period of at least 6 months (Criterion A). In addition, the behaviour, sexual urges, and fantasies must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (Criterion B).

Prevalence and Incidence

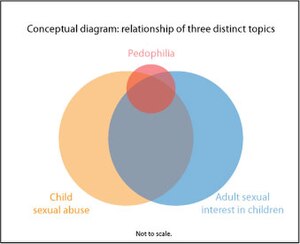

[edit | edit source]As a paraphilia offers pleasure, many individuals affected do not seek psychiatric treatment. Individuals who feel distressed may still avoid confiding in a doctor or psychiatrist out of shame (Raymond & Grant, 2008). Some paraphilias appear to be more common than others. Masochism, sadism and fetishism appear to be the most commonly encounter paraphilias.In comparison, within clinics that treat sex offenders who have criminal chargers, the most commonly encountered paraphilia are pedophilia, voyeurism and exhibitionism (Raymond & Grant, 2008). Given that the actually incidence of paraphilias involving non-consenting individuals or the number of paraphiliacs who fail to seek psychiatric help is not known, the incidence of any one of the paraphilias is underreported (Raymond & Grant, 2008). The prevalence of paraphilias is much higher in men than women. Abel and Osborne (2000) estimate the sex ratio of 30 to 1.

|

Types of Paraphilias: The DSM-IV defines the following paraphilias:

|

The Motivation Behind Paraphilia

[edit | edit source]Etiology

[edit | edit source]What is the motivation behind paraphilia? The etiology of the paraphilias is not precisely known. Theories have been proposed and researchers have conducted experiments to examine the differences in individuals with these disorders compared with controls. The existing theories for paraphilia are biological explanations, psychoanalytic explanations and cognitive-behavioural and conditioning explanations (Weiderman, 2003).

Brain Imaging and Neuropsychological Testing

[edit | edit source]What effect does the brain have on perverse sexual behaviour? Can paraphilia be attributed to brain illness or damage? Research in this field has associated brain damage and hormonal problems to the motivation behind paraphilia (Kafka & Hennen, 1999). Clinicians have observed that after brain damage, whether it was due to an accident, surgery, epilepsy, or toxic substances, paraphilias may emerge (Briken, Habermann, Berner & Hill, 2005). Investigators have further observed a link between sexually abnormal behavior and temporal lobe impairment (Kafka & Hennen, 1999). Different theories have been proposed to explain what the connection might be between brain abnormalities and paraphilias. They include the idea that a brain abnormality reduces the individual's control over paraphiliac impulses, that it releases sexual motivations otherwise repressed, and that it leads to paraphiliac motivations (Briken, Habermann, Berner & Hill, 2005). Studies have examined brain differences in sex offenders based on the idea that the temporal lobes of sex offenders have some abnormalities. Kafka and Hennen (1999) examined 41 pedophiles using CT scanning and found that left temporal parietal pathology was distinguished more often in pedophiles than in controls. In another study Kafka and Hennen (1999) compared CT scans of 51 men who had sexually assaulted females with 36 nonviolent non-sex offenders and found that right-sided temporal horn dilatation took place significantly more often in the sadists than in the controls. Wright, Nobrega, Langevin and Wortzman (1990) conducted CT scans of three groups of paraphiliacs sex offenders and one group of controls and found that the brains of paraphiliac sex offenders were moderately smaller in the left hemisphere compared with those of the controls. However, a number of studies have failed to show consistent imaging or neuropsychological differences. Wright et al. (1990) examined 160 extra-familial child sexual abusers, 123 incest perpetrators, 108 sexual aggressors against adult females, and 36 nonviolent nonsex offender controls with CT scans and the Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological Test Battery and found no difference in memory or imaging outcome variables in the groups of sex offenders compared with controls. Wright et al. (1990) further examined 36 nonviolent non-sex offenders and 91 incest perpetrators and found no difference in abnormalities on CT scan. Altogether, these results are mixed, with some studies finding neuropsychological and brain-imaging abnormalities in individuals with a history of child molestation and/or paraphilias compared with controls and some not.

The Monoamine Hypothesis

[edit | edit source]The monoamine hypothesis argues that the motivation behind paraphilias may derive from abnormal brain development leading to problems in neurological function (Kafka, 1997). Consequently, this leads to problems in the operation of the neurotransmitters (or monoamines) such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine (Kafka). In relation to the functions of these monoamines, evidence suggests that norepinephrine is important in the continuation of alertness, drive, and motivation whilst dopamine is vital for the experience of pleasure and reward and serotonin is involved in arousal, attention, and mood (Kafka, 1997). These monoamines act as neuromodulators mediating attention, learning, physiological function, affective states, goal motivated and motor behaviour, as well as appetitive states such as sleep, sex, thirst and appetite (Kafka). Furthermore, Kafka uggests that the attraction system in humans is related with high levels of dopamine, norepinephrine and decreased levels of serotonin. Additionally, Kafka argues that the motivation behind paraphilia is due to problems with serotonin levels.

Kafka (1997) conducted an experiment using male rats to examine the motivation behind male paraphilia. The results indicated that decreased levels of serotonin may increase appetitive sexual behaviour. Enhancing serotonin was found to inhibit or reduce the sexual appetitive behaviour in male rats (Kafka, 1997). Results further identified that an increase in noreadrenergic postsynaptic activity enhances sexual behaviour whilst certain noreadrenergic antagonists can have an inhibitory effect on sexual arousal. The results further found that a decrease in dopamine decreased the mammal's motivated behaviour, which included male sexual behaviour (Kafka, 1997). Therefore, the findings reported by Kafka illustrate how neurobiology can impact the motivation behind paraphilas sexual behaviour. For example, it is also suggested that for some individuals the motivation system can be adjusted by undermined neurotransmitter mechanisms. This may lower the threshold for sexually aggressive behavior by increasing the strength, salience, and duration of sexual goals, and desires, and weakening the action selection and control systems (Kafka). Therefore, the presence of extremely intense sexual feelings might over-ride an individual’s ability to control his sexual behaviour. Kafka states that the high incidence of depression, anxiety, impulsivity, compulsiveness, and aggression in paraphiliacs, and the reduction in serotonin levels are linked to all of these behavior abnormalities. Kafka further notes that alterations in norepinephrine have been reported in sensation-seeking individuals.

Sensation seeking has been suggested as a personality characteristic influencing the motivation behind paraphilias (Kafka & Hennen, 1999). Sensation seekers have low levels of monoamine oxidase (MAO) which is equivalent to individuals with paraphilia. MAO is a limbic system enzyme involved in breaking down brain neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin (Kafka, 1997). Dopamine contributes to the experiences of reward and therefore facilitates approach behaviours (Kafka, 1997). Serotonin contributes to a biological inhibition, and to the brains physiological “stop” system, which therefore inhibits approach behaviours (Kafka, 1997). In addition, Kafka (1997) conducted an experiment using animals to examine the association between sensation seeking behaviours in paraphiliacs and decrease in serotonin levels. The results illustrated that reduced serotonin positively correlates with sensation seeking characteristics in paraphiliacs. Sensation seekers tend to have high levels of dopamine, hence their biochemistry favours approach over inhibition (Kafka, 1997). They also tend to have relatively low levels of serotonin, hence their biochemistry fails to inhibit them from risks and new experiences. Furthermore, Gonadial hormones in males are related to sensation seeking and would also account for the sex differences in sensation seeking. Consequently, this can also suggest the sex differences in paraphiliacs, as paraphiliacs are predominately male.

|

Psychoanalytic Theory

[edit | edit source]Psychoanalytic theory considers the causes of paraphilias or “perversion” to early childhood (Guay, 2009). Freud (1856-1939) highlighted the idea that perversion could be a regression to perverse sexuality, which is an early state of sensual gratification (Wiederman, 2003). Psychoanalysts state that early perverse sexual experiences are common in patients with paraphilia and that they appear to be symbolically or actually re-enacted in the perverse fantasy (Wiederman, 2003). For example, the transvestic fetishist sometimes gives a record in which his mother dressed him in girls' clothes when he was a child, and the sadist gives a history that he was beaten. Among those paraphilias that constitute sexual abuse, as much as 30 percent of the paraphiliacs may themselves have been victims of sexual abuse before they were 18 years of age (Abel & Osborn, 2000). The method by which a victim becomes an abuser is understood as identification with the aggressor which is reliving a trauma by placing themselves in the power position (Wiederman, 2003). Psychoanalytic explanations rely on the concept of castration anxiety arose when a young boy first discovered that his mother did not have a penis (and therefore the young boy has the potential to lose his). The fetish object is then seen as an unconsious substitute for the mothers’ “lost” penis (Wiederman, 2003). Through fixating on the fetish item and perhaps involving sexual partners to wear or associate themselves with the items, the individual with the fetish maintains the unconscious fantasy that his partner has a penis (Wiederman, 2003). The psychoanalytic theory suggests that certain fetish items are chosen by paraphiliacs as the fetish relates to the last moment before the individual with the fetish, learnt of his mother’s castrated state (Wiederman, 2003).

Psychoanalytic theorists also explain the motivation behind paraphilia through their focus on object relations and possible problematic childhood attachment (Wiederman, 2003). The suggestion that individuals with paraphilia experienced childhood sexual abuse or trauma is based on an object relations perspective (Wiederman, 2003). The theory states that such abuse in real relationships with caregivers manifests itself as subsequent problems in the ability to establish and maintain healthy intimate relationships. Instead, the individual is motivated to satisfy sexual urges through nonrelationshal means (such as by reliance on a fetish object), pseudorelationships (eg, exhibitionism, voyeurism, or frotteurism), or relationships with partners that are based on disproportionate power (eg sexual masochism).

Cognitive-Behavioural and Learning Explanations

[edit | edit source]Cognitive behavioural and learning explanations also highlight the importance of early sexual experiences in relation to motivation behind paraphilia, although the significance is on their following thoughts and behaviours and their consequences (Marshall, 2007). For example a classical conditioning explanation of paraphilia is based on the principle that whatever stimuli were present during an initial sexual experience becomes paired with the sexual arousal and orgasm (Marshall, 2007). An example can be portrayed through using a Pavlovian paradigm where a conditioned stimulus (CS) is paired with an unconditioned stimulus (US) of genital stimulation and the unconditioned response (UR) of sexual pleasure (Atkins, 2004). As a result, in the future CS will produce the conditioned response (CR) of sexual arousal (Atkins, 2004). Foot fetishism can be used as an example. The sight and feeling of a foot, which touches the penis, can become a CS, the resulting erection (or orgasm) the US. Additionally, O'Donohue and Plaud (1994) conducted a conditioning model of sexual fetishism by pairing a visual stimulus of a pair of black boots with visual stimuli of attractive, nude women. The subjects in this study were three adult male psychologists. O’Donohue and Plaud (1994) measured sexual arousal by penile plethysmography. O’Donohue and Plaud (1994) defined a conditioned response as five successive penile responses to the conditioned stimulus (black boots). O’Donohue and Plaud (1994) also assessed stimulus generalization after criterion responding to the CS by presenting stimuli of other types of boots and shoes. The results found by O’Donohue and Plaud (1994) found that all three subjects showed criterion-conditioned responding, extinction of conditioned responding, and stimulus generalization. Another example of how the motivation behind parahilias is learned is when an individual looks into someone’s open window and witnesses’ nudity or sexual activity may become sexually aroused. If the individual continues to look and begins to masturbate or replays the experience for sexual satisfaction, voyeurism has now been assciated with sexual arousal and pleasure (Wiederman, 2003). The experience of orgasm reinforcers the voyeuristic behaviour or fantasy, more likely to happen again in the furture (operant conditioning). Each time the individual returns to voyeuristic behaviour or imagery during episodes of sexual arousal and orgasm, the association is strengthened (classical conditioning) (Wiederman, 2003).

Why do some individuals with a particular early sexual experience elaborate that experience into a paraphiliac interest whereas others do not? This could be due to biological predispositions toward being more motivated by sexual risk taking versus inhibition or to experiencing the initial sexual experiences during certain critical developmental periods (Wiederman, 2003). Additionally, it could be due to whether that sexual experience was perceived as positive or negative by the individual. Using voyeurism as another example, if the boy noticed the nudity or sexual activity and experienced embarrassment, he may have been motivated to look away and not think of the incident again (Wiederman, 2003). These combinations of factors illustrates why males are predominately more likely than females to develop paraphilia. In contrast to girls, boys have few prohibitions regarding sexuality, and having a penis and erections in comparison to a vagina and lubrication entails boys to be more conscious of their sexual arousal (Wiederman, 2003).

Social Learning Theory

[edit | edit source]Social learning theory suggests that an offender has somehow learned the paraphilia from his or her environment (Seligman & Hardenburg, 2000). This theory also incorporates "modeling", which suggests that the offender learned the behaviour from watching someone else behave in a similar fashion, or even by their own sexual abuse (Bradford, Bowlet and Pawlak, 1992). Social learning theory suggests that deviant sexual behaviours are learned in the same manner by which normative sexual behaviours and expressions are learned. Two surveys of sexual behaviour were conducted by Kinsey and Laumann (2003) the results concluded that aside from anatomy, most other aspects of human sexual behaviour were the product of learning and conditioning. Operant conditioning is a term used to describe behaviour which has been reinforced by reward or discouraged through punishment (Seligman & Hardenburg, 2000). Furthermore, Seligman and Hardenburg (2000) conducted a study using subjects between the ages of 21 and 43 years to test the hypothesis that sexual reinforcement increased penile responding. The researchers used sexually explicit scripts and neutral scripts which were read by the subjects. Each subject read six pages of sexually explicit material, during six sessions over a 2-week period. At the end of each session the experimental subjects were allowed to ejaculate (defined as the sexual reinforcement), while control subjects were required to read nonpornographic material until their tumescence decreased to within 25% of baseline. The researchers found that penile responding continued to increase over trials when the sexually explicit scripts were followed by sexual reinforcement. The control subjects demonstrated decreased responding over trials. The results of this study illustrate how positive reinforcement such as the ejaculation in the previous study increases a certain behaviour, in the previous instance, penile responding. However, this study can be related to the operant conditioning within paraphilias. A good example of reinforcement is the work of B.F Skinner and his work on operant conditioning. For example if a pedophile has a high sexual desire and need for sexual satisfaction, and by touching and abusing young children he is able to satisfy his sexual desires then this action (touching and abusing young children) is reinforced because it has satisfied a biological drive which was in a state of arousal. Therefore whenever we do something which is successful in satisfying a biological drive that behaviour is likely to become reinforced and so we will repeat it time and time again. This further can be related to the drive reduction theory.

|

Drive Reduction Theory

[edit | edit source]According to the theorist Clark Hull (1884-1952) humans have internal biological needs which motivate us to perform a certain way. These needs, or drives, are defined by Hull as internal states of arousal or tension which must be reduced (Bradford et al. 1992). According to this theory, we are driven to reduce these drives so that we may maintain a sense of internal calmness (Bradford, et al., 1992). Drive reduction theory states that when we do something which reduces the tension associated with a biological drive (that is in a state of arousal) then that action is reinforced (Bradford et al. 1992). As a result, drive reduction theory states that our biological drives play a big way in how we learn (Bradford et al, 1992). Furthermore, similar to the operant conditioning learning paradigm, the motivation behind paraphilias can be associated within the drive reduction theory. For example, in relation to an individual with exhibitionism their biological drive and arousal is produced by exposure of the genitals to an unknown woman or girl (Bradford, et al., 1992). When exhibitionists experience their biological drive or irresistible impulse, they consequently expose their genitals which, as a result, reduces the tension associated with that biological drive. Therefore, as it reduces the tension, the action of exposing ones’ genitals is reinforced.

Courtship Disorder Theory

[edit | edit source]Freund suggested the concept of “courtship disorder” to explain the motivation behind paraphilias (Freund, Scher & Hucker, 1983). The theory of courtship disorder suggests voyeurism, exhibitionism, frotteurism, and preferential rape are expressions of a common underlying disturbance. Freund et al. (1983) state that courtship is characterised by a set of preferences for a sequence of erotic sensory stimuli and erotic activities and suggests that in paraphiliacs this has been disrupted (Freund et al., 1983). Freund et al., (1983) described an idealided sequence of courtship behaviours as involving four phases:

- Location of a potential partner (Finding phase, if a patient were “trapped” in this phase, he would become a voyeur)

- Pretactile Interaction (An affiliative phase, verbal and nonverbal communications with a prospective partner; with deviancy resulting in exhibitionism)

- Tactile Interaction (in which physical contact is made; with a deviation resulting in frotteurism)

- Effecting genital union (in which sexual intercourse occurs; with a deviancy resulting in rape).

Case Study[edit | edit source]A Victim of a Paraphiliac Crime A white female aged 34 years with shoulder length brown hair, had just placed her 9-year-old son in bed. An intruder broke into her back bedroom window and surprised her in the living room. He placed a large hunting knife next to her throat and told her to do as he said and not to scream or fight him or he would kill her and her child. Fearing for her life and for the life of her son, the victim complied with all his commands. The perpetrator, a white male aged 25 to 30 years of age, ordered her to take off all articles of clothing, which she did. He then handed her a white piece of cloth, possibly a tee shirt and told her to place it around her eyes. The cloth served as a blindfold. Once the blindfold was in place, he handed her a bra and panties and ordered her to put them on. He ordered her to remain still as he slowly cut the bra and panties from her body. He then took her by the arm and led her into the bathroom, where he made her bend over the sink. He penetrated her vaginally from the rear with his penis. As he raped her, he began cutting her hair with his knife. The victim reported that the perpetrator appeared to become more sexually aroused as he cut her hair at which time he ejaculated. When the perpetrator finished, he told her to remain bent over the sink for 5 min or he would kill her and her child. When she was reasonably sure that he had left the premises, she stood upright and immediately ran into her son’s bedroom to find him unharmed. She went back into the bathroom where she looked in the mirror. The perpetrator had cut large chunks of her hair, yet only a few strands of hair lay on the bathroom floor. The perpetrator had taken the hair with him. He had also taken the undergarments he had cut off her, as well as the blindfold. Analysing the Case Study:[edit | edit source]

her to remove all her clothes. The act of having her remove her own clothing may have been sexually arousing to the perpetrator, what type of paraphilia may this be?

Answers[edit | edit source]1: voyeurism 2: Sexual Arousal 3: Sadistic Sadism 4: Yes |

Treatment

[edit | edit source]The same theoretical models which explained the motivation behind paraphilia, psychoanalytic, biological and cognitive-behavioural domains, also help suggest adequate treatment for paraphilia. Biological treatment approaches entail controlling sexual drive and decreasing compulsivity (Wiederman, 2003). Cognitive-behavioural approaches engage in breaking the association between inappropriate stimuli and sexual arousal, reinforcing more appropriate sexual stimuli, and relapse prevention (Wiederman, 2003).

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy

[edit | edit source]The behavioural therapies aim to teach patients techniques that they can use to decrease deviant sexual drives and to maintain control of their behaviours (Wiederman, 2003). These include olfactory aversion, covert sensitisation, various masturbatory reconditioning techniques, modified aversive behavioural rehearsal, and imaginal desensitisation training. Furthermore, behavioural treatment is to “unlearn” the association between the inappropriate stimulus and sexual arousal (Wiederman, 2003). Normally, the deviant association has been strengthened over time and over situations. The term satiation is used to involve pairing the stimulus with lack of arousal (Wiederman, 2003). Satiation involves the individual to masturbate to the preferred stimulus or fantasy images, then to continue after orgasm (Wiederman, 2003). After orgasm, the paraphilic interest and the additional physical stimulation will hardly hold the attraction they did prior to orgasm. Marshall (2000) performed two single-case experiments using satiation therapy to reduce deviant sexual arousal. The first involved a 33-year old male pedophile with arousal patterns to shoes and underwear as well as to female children, while the second involved a 36 year old male pedophile with strong adult homosexual interests. The subjects were each instructed to fantasise about a targeted stimulus for 1 hr while continuously masturbating and reporting the fantasies aloud. If the subjects ejaculated, they were instructed to reinitiate masturbation immediately. Marshall concluded that results indicated that the satiation technique in both cases significantly decreased deviant arousal patterns. These results could be due to the fact that the satiation served as a causative mechanism of behavioural change (Wiederman, 2003).

The behavioural treatment involving pairing the inappropriate stimulus with an aversive experience is called covert sensitisation (Wiederman, 2003. Covert sensitisation involves mentally pairing the preferred stimulus with negative imagery. Wiederman (2003) illustrated an example, when a man fantasises about a woman in high-heeled shoes walking on his chest and becomes aware that he is beginning to have such fantasies, he is to switch to aversive imagery, such as the woman vomiting first, followed by his vomiting. Aversion training involves the more direct association of the inappropriate stimulus and an actual negative experience, such as electric shock or an aversive odour (Wiederman, 2003). A study conducted by Abel and Osborn (2000) studied six males (exhibitionists with histories of voyeurism, 2 transvestites, and 1 masochist) between 21 and 31 years of age. Five of the subjects were randomly assigned to a contingent shock condition, and one subject to a non-contingent schedule. The researchers found that penile responding to the deviant tape was suppressed up to the 18-week follow-up period as well as to deviant tapes that were not used in treatment (Abel & Osborn, 2000).

Biological Treatments

[edit | edit source]Biological approaches involve suppressing sexual drive and decreasing compulsivity (Wiederman, 2003). The antiandrogens cyproterone acetate (CPA) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) are the most commonly prescribed biological treatments for the control of paraphilia (Wiederman, 2003). Common side effects of antiandrogens include weight gain, fatigue, hypertension, headaches, hyperglycemia, leg cramps and diminished spermatogenesis (Wiederman, 2003.

MPA lowers testosterone by reducing the production of testosterone, and by significantly increasing its metabolic rate by interfering with the binding of testosterone to sex-hormone binding globulin (Wiederman, 2003). CPA inhibits testosterone directly at androgen receptor sites and also exhibits antigonadotrophic effects (Wiederman, 2003). Hormones such as MPA and CPA decrease the level of circulating testosterone thus reducing sex drive and aggression. These hormones result in reduction of frequency of erections, sexual fantasies and initiations of sexual behaviours including masturbation and intercourse(Wiederman, 2003). Hormones are typically used together with behavioural and cognitive treatments.

Research data using mammals to examine the correlation between sexual behavior and monoamine neurotransmitters suggest that decreased serotonin and increased dopamine neurotransmission may promote sexual behavior and, conversely, enhancing serotonin activity or inhibiting dopamine receptors in the brain may inhibit sexual behavior in some mammalian species (Kafka, 1997). Furthermore, Kafka (1997) reported a case-study of an exhibitionist treated with fluoxetine hydrochloride, which had a reduction in paraphilic fantasy. Three case-reports involving a pedophile, an exhibitionist, and a voyeur were also reported as successfully treated with fluoxetine. Kafka (1997) reported on three cases of paraphilia, two of which were considerably improved over a 3 month follow-up period.

Chapter Summary

[edit | edit source]Paraphilia is recurring, intensely arousing fantasies, sexual urges or behaviours that involve nonhuman objects, that involve the suffering or humiliation of oneself, one's partner, children, or non-consenting others, and that occur over a period of at least sex months (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The motivation behind paraphilia has been demonstrated using biological, psychoanalytic, cognitive-behavioural and learning explanations. Biological explanations have included the idea that paraphilia is motivated by hormones and brain abnormalities. However, there has been mixed research evidence regarding the biological theory. Psychoanalytic explanations date back to Freud, and were focused primarily on the development of fetishes. This theory relied on the idea of castration anxiety and problematic childhood attachment. Cognitive behavioural and learning explanations also emphasised early childhood sexual experiences. The emphasis was on thoughts and behaviours and their consequences (operant and classical conditioning).

The treatment of paraphilia is also based on these theoretical frame-works. Biological approaches involve suppressing sexual drive and decreasing compulsivity. Cognitive-behavioural approaches involve breaking the association between unacceptable stimuli and sexual stimuli. However the most effective treatment combines biological and cognitive-behavioural interventions.

References

[edit | edit source]References: Abel,G.G., & Osborn, C. (1992). The paraphilias. The extent and nature of sexually deviant and criminal behaviour. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15, 675-687.

Akins, C.K. (2004). The role of pavlovian conditioning in sexual behaviour: A comparative analysis of human and nonhuman animals. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 17, 241-262.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., DSM-IV). Washington, DC: Author.

Bradford, J.M., Boulet, J., & Pawlak, A. (1992). The paraphilias: A multiplicity of deviant behaviours. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 104-108.

Briken, P., Habermann, N., Berner, W. & Hill, A. (2005). The influence of brain abnormalities on psychosocial development, criminal history and paraphilias in sexual murderers. Journal of Forensic Science, 50, 1204-8.

Freund, K., Scher, H., & Hucker, S. (1983). The courtship disorders. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 12, 369-379.

Guay, D. R.P. (2009). Drug treatment of paraphilic and nonparaphilic sexual disorders. Clinical Therapeutics, 31, 1-31.

Kafka, M. P( 1997). Hypersexual desire in males: An operational definition and implications for males with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 26, 505-526.

Kafka, M.P. & Hennen, J. (1999). The paraphilia-related disorders: An empirical investigation of nonparaphilic hypersexuality disorders in outpatient males. Journal of Sex Marital Therapy, 25, 305-319.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W.R., & Martin, C.E. (2003). Sexual behaviour in the human male. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 894-898.

Marshall, W.L. (2007). Diagnostic issues, multiple paraphilias, and comorbid disorders in sexual offenders: Their incidence and treatment. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 12, 16-35.

O'Donohue, W., & Plaud, J. (1994). The conditioning of human sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 23, 321-344.

Rahman, Q., & Symeonides, D.J. (2007). Neurodevelopmental correlates of paraphilic sexual interests in men. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 37, 166-172.

Raymond, N.C., & Grant, J.E. (2008). Sexual disorders: Dysfunction, gender identity, and paraphilias. The Medical Basis of Psychiatry, 1, 267-283.

Seligman, L., & Hardenburg, S.A. (2000). Assessment and treatment of paraphilias. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78, 107-113.

Wiederman, M.W. (2003). Paraphilia and fetishism. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 11, 315-321.