Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Equanimity

What is equanimity and how can it be developed?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

The field of contemplative science is quickly emerging into a large topic for discussion, emerging from the course of history and Buddhist practice (Williams & Kabat-Zinn, 2011). Whilst mindfulness itself has already been proposed as a measurable outcome of contemplative practice, the concept encompasses many varied components, some of which have been considered to be better characterised under equanimity. Equanimity has not been discussed extensively in Western psychological theory, however, appears in linked concepts such as non-judgment, acceptance, non-reactivity and non-strivinge (Kang, 2019). Equanimity at this point can be defined as the even-minded, balanced (see figure 1), composed mental state or dispositional tendency consistent towards all objects and experiences, regardless of the origin or affective valence (neutral, pleasant or unpleasant) (Bernhard, 2013).

Many attempts to describe equanimity in modern psychological terms have been made, the most frequently cited being Jon Kabat-Zinn's "paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgementally" (Kabat-Zinn, 1990, p. 13). Equanimity, the grounding for wisdom, freedom, compassion and love, is considered as one of the four sublime emotions of the Buddhist practice (Fronsdal & Pandita, 2005). A mind filled with Equanimity has been described by the Buddha as exalted, abundant, without hostility, immeasurable, and without ill-will (Fronsdal & Pandita, 2005).

Mindfulness-based meditation and equanimity have a powerful effect across a variety of psychological outcomes, some of which include changes in relationship issues, emotionality, consistent attention and health (Orme-Johnson & Dillbeck, 2014). A variety of psychological and neurological mechanisms which underlie these outcomes have since been identified (Gu, 2015). Through a Buddhism perspective, mindfulness meditation is an effective way to achieve an emotional, attentional and cognitive balance of the mind (Ekman & Davidson, 2005). Many recent authors have suggested utilising equanimity as a general outcome in contemplative research, however pre-existing mindfulness scales do not take this suggestion into account (Desbordes & Negi, 2013). Although clinical and scientific interpretations of mindfulness are not entirely aligned with Buddhist tradition, several components of the practice have continued interest in modern psychology today.

|

Focus questions:

|

What is equanimity?

[edit | edit source]Equanimity in Theravadan Buddhist literature refers to "neutral feeling", a mental experience that is neither unpleasant nor pleasant, involving neither dampening nor intensifying mental states (Desbordes & Negi, 2013).

| “ | As a solid mass of rock is not stirred by the wind, so a sage is not moved by praise and blame. As a deep lake is clear and undisturbed, so a sage becomes clear upon hearing the Dharma. Virtuous people always let go. They don’t prattle about pleasures and desires. Touched by happiness and then by suffering, the sage shows no sign of being elated or depressed - The Buddha (Dhammapada) |

” |

The Buddhist practice explains equanimity as an even mind which is to remain this way in the face of every experience, regardless of whether pleasure or pain are present or not (Ekkman & Davidson, 2005). The Western translation of this message is to consider equanimity a mental state that will not be swayed by preferences or biases, and balances (see figure 1) reactions to both misery and joy, protecting oneself from emotional agitation (Desbordes & Negi, 2013).

Equanimity is considered an important, implicit concept within the psychoanalytical approach to psychology. Psychoanalysis's believe it is of importance for emotions to be viewed through an even-minded attitude and free association by approaching each emotion with free-floating attention (Paris, 2017). Sigmund Freud (see figure 2) advised psychoanalysts to have patients report their internal perceptions, whether that be feelings, memories or thoughts, without avoiding proposed unacceptable, repressed or suppressed feelings (Freud, 1964). Whilst early psychoanalysts did not necessarily promote equanimity practice or meditation, the concept that all types of emotions should be carried into conscious awareness through an overarching attitude of acceptance is considered the grounding foundation of psychoanalytic theory and equanimity today.

|

Test your knowledge

Choose the correct answer and click "Submit":

|

What does equanimity feel like?

[edit | edit source]There have been many proposed factors involved in describing what equanimity feels like. Bishop et al. (2004) proposed a two-component model of mindfulness (equanimity), with the first factor being self-regulated attention. The purpose of self-regulation is to maintain attention on present-moment experience and the second factor being an attitude of openness and acceptance. Shapiro et al. (2006) later proposed a three-component model which further separate attention on intention and purpose, whilst also including attitude as the third component. Baer et al. (2008) proposed a five-factor model of mindfulness including two factors of “non-judging of inner experience” and “non-reactivity to inner experience.” Each of these definitions, the original Buddhist definition and many others surrounding mindfulness and equanimity scales share the common overarching themes of an "attitude of openness and acceptance", "remaining balanced in all experiences" and "remaining constant".

Attitude of openness and acceptance

[edit | edit source]Equanimity is heavily considered to revolve around acceptance, being neutral with feelings and accepting all feelings. The Buddhist practice of equanimity suggests mindful acceptance to be about allowing oneself to feel whatever should arise in any given moment, without discomfort (Fronsdal & Pandita, 2005). Various recent Western definitions of mindfulness highlight the common component of equanimity as an "attitude of openness and acceptance". Baer, Smith and Lykins (2006) define this factor as ‘‘a state of being in which individuals bring their attention to the experiences occurring in the present moment, in a non-judgmental or accepting way’’ (p. 27).

Remaining balanced across all experiences

[edit | edit source]Equanimity manifests a balanced reaction to all experiences, that being both the joys and miseries of each experience that protect the mind from emotional agitation, which highlights its significance in emotional regulation. To remain balanced is to welcome all experiences, without turning away from painful emotions or situations. However, it has been highlighted that this simultaneously does not mean getting stuck in the emotion or situation of each experience, but to embrace each emotion (Fronsdal & Pandita, 2005). By remaining centred through observing and understanding each emotion, fuelling the emotion you're already feeling (Kang, 2019).

Remaining constant

[edit | edit source]Equanimity creates constancy across inconsistent events, remaining at the state of mental composure and calmness in all situations. Remaining even-tempered and non-reactive when something abrupt or upsetting occurs (Kang, 2019). Equanimity is based around non-attachment and impermanence. Whether a situation is good or bad, remain unattached, unbothered and undisturbed as you approach all situations consistently in a calm and neutral way (Kang, 2019).

|

Sarah is a 21-year-old university student who studies full-time, trains as a full-time soccer athlete and on top of this she also tries to fit in working 2 casual jobs. Whilst Sarah is aware of her busy schedule, she usually enjoys having a full plate. Except recently, Sarah has become more aware that this business has caused her to become easily irritated. She has been snapping back at her teachers, coaches, friends and family in situations which she later doesn't deem necessary. Her temper, quick emotion infused reactions and negative mindset seem to have heightened, and she is beginning to notice this taking a toll on her happiness, daily achievements and relationships. What should Sarah aim to try and implement into her everyday life? |

Religious frameworks

[edit | edit source]The virtues and values behind equanimity are an important part of multiple major religions and are advocated by a number of particularly interesting ancient philosophies.

Table 1

Religious frameworks connected to equanimity

| Hinduism | Buddhism | Yoga | Islam | Baha'i |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - The term for equanimity is समत्व samatvam in Hinduism (Agrawal, 2013).

- The initial syllable sama translates to "even" or "equal" (Agrawal, 2013). - The following syllable sāmya translates to "equal consideration towards all human beings" (Agrawal, 2013). |

- Equanimity is considered one of the four sublime attitudes.

- Thought of as neither a thought or emotion, rather a steady consciousness and realisation of transcience (see figure 3) (Bernhard, 2013). - Buddhists consider equanimity as "the ground for wisdom and freedom, the protector of compassion and love" (Bernhard, 2013). |

- The term for equanimity is Upeksha and is considered one of the four sublime attitudes (Feuerstein, 2011).

- Upeksha Yoga practice considers equanimity as the single most important aspect of yoga (Agrawal, 2013). - Equanimity is said to be attained through regular meditative practices, regular practice of asanas and pranayama and mental disciplines. |

- The word “Islam” itself comes from the Arabic word 'aslama', a word which denotes the peace that comes from total and complete acceptance and surrender (Agrawal, 2013).

- A Muslim would typically behold that everything happening is meant to be, and stems from the ultimate wisdom of God; hence, being a Muslim can therefore be understood to mean that one is in a state of equanimity (Agrawal, 2013). |

- Writings of the Baha'i faith are filled with references to divine attributes, of which equanimity is one (Prabhupada, 1990).

- Similar in intent and more frequently used than "equanimity" in the Baha'i writings are "detachment" and "selflessness" disposing human beings to free themselves from inordinate reactions to the changes and chances of the world (Agrawal, 2013). |

|

Test your knowledge

Choose the correct answer and click "Submit":

|

How to develop equanimity

[edit | edit source]Whilst many mindfulness researchers and psychologists have identified various concepts as a guide towards cultivating equanimity, the development journey is extremely individualised. Five common areas of mindfulness have been consistently identified as crucial aspects for cultivating equanimity through recent mindfulness research and psychological application (Shapiro et al., 2006). Having a "clear objective", "cultivating and practicing mindfulness first", "starting with small events", "incorporating equanimity into meditation practices" and "knowing the difference between equanimity and indifference" have thus far been considered consistently essential in the development of equanimity.

Clear objective

[edit | edit source]The goal is not to aim for 100% equanimity at all times, but to train the mind to be less reactive and attached to situations (Yang, 2019). It will help to get stronger emotionally and allow for better solutions when dealing with unforeseen and difficult circumstances. The more practice, the easier it will become, and more simple to return to the state of equanimity in various situations (Bernhard, 2013).

Cultivate and practice mindfulness first

[edit | edit source]Equanimity and mindfulness go hand in hand. Without being mindful, there is no way to tell if one is balanced or not. Knowing how to become centred will allow for clarity when you are off-centre (Yang, 2019). If one is attached to a situation, mindfulness will remind them of where their centre is and how the situation has moved them off-centre. With this awareness, one can then choose whether to be enticed into the situation, or to release the attachment to cultivate equanimity once more (Yang, 2019).

Start with small events

[edit | edit source]Consider starting with smaller events in life.

|

Example

Consider the question's "am I able to stay calm and composed during this circumstance? Am I about to lose my balance?" (Yang, 2019). |

Once able to remain calm during these situations, the next step is to move onto larger events.

Incorporate equanimity into meditation practices

[edit | edit source]To cultivate equanimity, incorporating it into your daily meditation practices can be a good first step.

|

Example

During meditation bring yourself to a situation that makes you uncomfortable, or that you don't like. Feel the emotions this floods you with, then let them go. Next, bring an event to mind that you enjoy or like, feel those emotions then also let them go. Alternate between good and bad until you are non-reactive to them (Yang, 2019). By flipping between the good and bad, you will gain emotional stability and strength for all scenarios. |

Know the difference between equanimity and indifference

[edit | edit source]Equanimity focusses on opening your heart, whilst indifference focusses on closing your heart. Equanimity does not mean not caring about anything or have no emotions towards anything, that is more so indifferent and apathetic. Indifference includes numbing oneself so that unwanted emotions are no longer felt, this is aversion of a situation, not the acceptance found in equanimity (Yang, 2019). Equanimity is about being emotionally aware, but not being overly enticed by them.

|

Sarah's first step into making a change is by looking into practicing mindfulness, and more specifically, equanimity. Sarah's high temper and negative mindset have allowed her to identify cultivating equanimity as a specific, relevant goal to her current situation. Sarah begins by understanding that it will be a long process, that she will not find herself utilising equanimity 100% perfectly all the time, but wants to do her best nonetheless. Sarah begins practicing mindfulness, allowing herself to be consistently aware of her feelings, emotions, surroundings and thoughts. In situations where Sarah becomes mindful of her rising temperament, she asks herself "can I stay calm right now, why, why not?". Sarah is enjoying practicing mindfulness, and introducing equanimity practice into specific situations, and is looking forward to cultivating the consistent neutral feeling she is striving for. As a result of her time practicing mindfulness and equanimity, Sarah is beginning to find herself able to process situations where she would typically feel uncomfortable and frustrated, and without reacting negatively, has been able to assess the more appropriate way to respond. Although a small step in Sarah's journey, Sarah is already seeing the benefits of equanimity practice. |

Measuring equanimity

[edit | edit source]When trying to cultivate equanimity, it can be difficult to determine personal growth, progress and development without adequate forms of measurement. Measuring equanimity whether objectively or subjectively, has recently presented with many challenges and areas for improvement. Various studies have used a variety of physiological, psychological and neuro-imaging techniques to assess equanimity and emotional response through longitudinal studies with beginners, and experienced meditational practitioners. Various researchers have proposed self-report scales targeting numerous areas around equanimity, but not equanimity itself, and physiological measures associated with the overall concept of mindfulness, rather than equanimity specifically (Gu, 2015). Most research scales have shown to lack strong theoretical framework and disclose a lack of a common consensus around the concepts of equanimity, or have proposed findings opening room for further research.

Self-report

[edit | edit source]Various researchers have proposed that self-report scales on equanimity lack suitable theoretical framework, revealing a lack of a common agreement around the constructs of equanimity. Some earlier developed self-report scales include Büssing et al. (2006) questionnaire measuring distinct expressions of spirituality with equanimity being one of seven factors, comprised of "trying to practice equanimity,” “trying to achieve a calm spirit,” and “meditate”. It was found this scale measured a subject's efforts towards equanimity, rather equanimity directly. Lundman et al. (2007) conceptualised equanimity as a factor of resilience, defining equanimity through questions such as, “I take things 1 day at a time" and “I do not dwell on things that I can’t do anything about". This scale was found to conflate multiple constructs and struggle to differentiate apathy and equanimity. More recent scales have developed assessment of other constructs closely related to equanimity, such as Sahdra et al. (2010) Nonattachment Scale (NAS) and The Experience Questionnaire (2010) founded by Teasdale, Segal, and Williams assessing decentering and rumination. A single scale is yet to be identified and favoured for measuring equanimity, with many of these preexisting self-report measures measuring the constructs around equanimity, rather than equanimity itself. Other issues these measures have shown are consistent with that of mindfulness questionnaires, including a lack of theoretical framework, no single consensus on what the construct is, interpretation of items within a scale, discrepancies between reality and self-report.

|

Test your knowledge

Choose the correct answer and click "Submit":

|

Physiological measures

[edit | edit source]Physiological measures that have been suggested to objectively measure equanimity include endocrine, autonomic and inflammatory markers. Autonomic function has been utilised for decades in psychophysiology to assess how emotions are manifested throughout the body, including skin conductance, respiratory rate, heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV), one example being the fight-or-flight response (Cannon, 1915). It has recently been proposed that these indices may be useful in assessing equanimity. One recent study utilised HRV to measure emotional equanimity and motivational orientation towards academic performance in university students (Gramzow et al. 2008). Emotional equanimity was defined as “keeping a cool head when thinking about academic performance and a “calm and composed state”. Other markers relevant to emotion include immune markers and stress hormones like cortisol and inflammatory cytokines (Sternberg, 2000). These markers can be measured during an emotional challenge, such as the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) where the subject, in front of an audience, performs a challenging mental arithmetic task increasing cortisol and inflammatory cytokines (Kirschbaum et al. 1993). Another potential measure of equanimity is the activation of facial muscles involved in expression (Ekman & Davidson, 2005). While physiological measurements provide objective assessment, it has been suggested that self-reports could be used in combination with physiological measures to help distinguish equanimity from other forms of emotional regulation.

|

Peng, an experienced Buddhist monk is part of a small experiment comparing startle response during meditation and distraction. Peng's electrical activity of the muscles around the eye (controlling blinking) are measured through both different types of meditation and distraction, as a loud noise happens. When the loud noise happens during his meditative state of equanimity known as "Open Awareness", Peng shows a small startle response. In comparison to his startle response during other forms of meditation, such as "Focussed Concentration" and during distraction. Peng's experience suggests that, not only can external physiological measures measure equanimity, but also the different levels of equanimity, as suggested by the different meditation practices and reactions. |

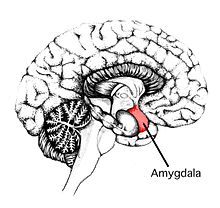

Neuro-imaging

[edit | edit source]A few recent neuro-imaging studies have disclosed possible neural mechanisms underlying mindfulness, and potentially equanimity, through various emotional challenges, such as pain. These studies were not designed to investigate equanimity, but offer particular insight into how equanimity could display in the brain. These recent neuro-imaging studies have investigated neural correlations between emotional regulation and the brain, particularly in the context of meditation. Many of these studies have highlighted the complex role of the amygdala (see figure 4), particularly in orienting attention towards emotionally significant stimuli (Cannon, 1915). Findings have suggested that emotional regulation strategies, such as reappraisal, promote decreased amygdala activation (Beauregard et al. 2001). Several other neuro-imaging studies around meditation have found meditators to react less intensely to emotional stimuli during a state of mindfulness, then during rest (Desbordes & Negi, 2013). Whilst no studies have investigated the application of neuro-imaging on equanimity and the brain, the mentioned mindfulness studies and the like have demonstrated a promising field for future research.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Equanimity is the even-mindedness, balanced, composed mental state which remains consistent towards all experiences, objects and people, regardless of the origin or affective valence (neutral, pleasant or unpleasant). Equanimity is the grounding wisdom for freedom, compassion and love and is considered to be one of the most sublime emotions of Buddhist practice (Fronsdal & Pandita, 2005). Mindfulness-based meditation, paired with equanimity, has a positive effect across a variety of psychological outcomes, including emotionality, health and relationships (Sedlmeier et al., 2012).

Equanimity, as a psychological concept, has been difficult to define as many people look at it in different ways. This has made measuring equanimity difficult. Recent studies have used a variety of physiological, psychological and neuro-imaging techniques to assess equanimity including through longitudinal studies with beginning and experienced meditational practitioners. Self-report scales target numerous concepts similar to equanimity, but not equanimity itself, and physiological measures associated with the overall concept of mindfulness, rather than equanimity specifically (Büssing et al. 2006). Most research scales lack a strong theoretical framework and consensus about the concepts of equanimity, leaving many areas for future research.

Although a newly popularised concept, equanimity is a lifestyle that can be cultivated by anyone. Being closely related to various ancient religious practices of meditation and mindfulness, the overarching beliefs and factors originated many years ago, but can now be seen as a common phenomenon to strive towards. Whilst there are still many approaches, perspectives and interpretations around the same idea of equanimity, the progression in conceptualisation over recent years suggests room for a large shift in orientation and accordance in coming years.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Equanimity (Wikipedia)

- Buddhism (Wikipedia)

- Hinduism (Wikipedia)

- Yoga (Wikipedia)

- Islam (Wikipedia)

- Baha'i (Wikipedia)

- Four sublime attitudes (Wikipedia)

- Mindfulness (Book chapter, 2013)

- Mindfulness (Book chapter, 2011)

- Emotional regulation through meditation (Book chapter, 2014)

- Mindfulness, meditation and happiness (Book chapter, 2015)

References

[edit | edit source]Beauregard, M., Lévesque, J., & Bourgouin, P. Neural correlates of conscious self-regulation of emotion. J Neurosci, 21(18), 165

Baer, R., Smith, G., & Lykins, E. (2008). Construct Validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Meditating and Nonmeditating Samples. Sage Journals, 15(3), 329-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003

Bernhard, T. (2013). How to wake up: a Buddhist-inspired guide to navigating joy and sorrow. Wisdom Publications.

Bishop, S., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N., Carmody, J., & Segal, Z. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Bussing, A., Foller-Mancini, A., Gidley, J., & Heusser, P. (2006). Aspects of spirituality in adolescents. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 15(1), 25-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13644360903565524

Cannon, W. B. (1915). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage: An account of recent researches into the function of emotional excitement. D Appleton & Company, 1(3), 1-15 https://doi.org/10.1037/10013-000

Desbordes, G., & Negi, L. (2013). A new era for mind studies: training investigators in both scientific and contemplative methods of inquiry. Mindfulness, 7(1), 741-749, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00741

Ekman, P., & Davidson, R. (2005). Buddhist and Psychological Perspectives on Emotions and Well-Being. Mindfulness, 14(2), 59-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00335.x

Feuerstein, G. (2011). The encyclopedia of yoga and tantra. Shambhala.

Freud, S. (1964). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Macmillan.

Fronsdal, G., & Pandita, S. (2005). A Perfect Balance. The Buddhist Review, 15(2), 12-14. Retrieved from: https://tricycle.org/magazine/perfect-balance/

Gramzow, R., Willard, G., & Mendes, B. (2008). Big tales and cool heads: academic exaggeration is related to cardiac vagal reactivity. Emotion, 8(1), 138-44. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F1528-3542.8.1.138

Gu, J. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Mindfulness, 37(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Delacorte

Kang, Y. (2019). How to cultivate equanimity and be emotionally strong. Finding Inner Peace, 6(1), 113-119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717692306

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K., & Hellhammer, D. (1993). The 'Trier Social Stress Test'--a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1), 76-81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000119004

King, W. (1963) Buddhism and Christianity: some bridges of understanding. Routledge

Kornfield, J. (1996). Still Forest Pool. Quest Books.

Liebenson, N. (1999). Cultivating equanimity. Barre Centre for Buddhist Studies, 19(2), 1-3. Retrieved from: https://www.buddhistinquiry.org/article/cultivating-equanimity-2/

Lundman, B., Strandberg, G., Eisemann, M., Gustafson, Y., & Brulin, C. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the resilience scale. Scand J Caring Sciences, 21(2), 229-237. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230818879_B_Lundman_Strandberg_G_Eisemann_M_Gustafson_Y_Brulin_C_Psychometric_properties_of_the_Swedish_version_of_the_resilience_scale_Scand_J_Caring_Sciences_212_229-237_2007

Mulla, Z. R., & Krishnan, V. R. (2014) Karma-Yoga: The Indian model of moral development. J Bus Ethics, 123, 339-351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1842-8

Nikaya, D. (1987). The long discourses of the Buddha: a translation of the Digha Nikaya. Wisdom Puplications

Orme-Johnson, D., & Dillbeck, M. (2014). Methodological concerns for meta-analyses of meditation. Journal of Psychological Science, 140(2), 610–616. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035074

Paris J. (2017). Is psychoanalysis still relevant to psychiatry? Canadian journal of psychiatry, 62(5), 308–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717692306

Prabhupada, A. (1990). Bhagavad-Gita As It Is. Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Radwan, J. (2018). Leadership and communication in the Bhagavad Gita: unity, duty and equanimity. Journal of Bhagavad Gita, 97(8), 319-321. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99611-0_5

Sahdra, B., Shaver, P., & Brown, K. (2010). A Scale to Measure Nonattachment: A Buddhist Complement to Western Research on Attachment and Adaptive Functioning. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(2), 116-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890903425960

Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Astin, J., & Freedman, B (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol, 62(3), 373-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237

Sternberg, E. (2000) The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. Freeman & Company.

Williams, J., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2011). Mindfulness: disverse perspectives on its meaning, origins, and multiple applications at the intersection of science and dharma. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564811