Motivation and emotion/Book/2019/Psilocybin and emotion

What are the emotional effects of psilocybin?

Overview

[edit | edit source]This chapter focuses on psilocybin's effects on human emotion. Perceptive understanding with respect to neural structures involved in psilocybin use, together with detailed subjective accounts of experience within clinical settings, contributes to our understanding of emotional effects, exploring the historical context of psilocybin use, and recent therapeutic applications.

|

Focus

Relationship between psilocybin and emotion. Psychological theories of emotion relating to effects of psilocybin. Findings of modern research of psilocybin use. |

Emotion

Emotion is defined as a complicated state of feeling, resulting in psychological and physiological changes that influence thought and behaviour. (Studerus, Kometer, Hasler, & Vollenweider, 2011). See Figure 1.

Psilocybin

Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine), a naturally occurring serotonergic compound, is one of the main psychoactive compounds found in a group of hallucinogenic fungi of the genus psilocybe, often referred to as "magic mushrooms" (Studerus et al., 2011). See list of psilocybin mushroom species. These mushrooms belong to group of drugs called psychedelics, currently considered a controlled substance in most countries. See legal status of psilocybin mushrooms. In low doses, psilocybin dramatically alters a person's perception of reality in unpredictable ways, through cognition, mood, thoughts, emotion and sense of self. Effects typically last between 2 and 8 hours depending on dosage (Dinis-Oliveira, 2017).

History

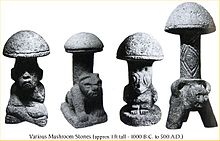

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin mushrooms (see Figure 2) have been used in human medicine, healing, and religious rituals in various cultures for centuries. See Table 1. Recently, psilocybin has been ultilised as a research tool for modelling psychosis, and scientifically studied for its therapeutic effects. Being a readily available natural hallucinogen, it is also popular amongst recreational users (Tylš et al., 2014).

Early use

[edit | edit source]

Table 1.

Examples of early psilocybin use

| Cultural representation | Type | Authors |

| Mesoamerican pre-Columbian societies

(Mazatec, Olmec, Zapotec, Maya, and Aztec cultures) See Figure 3. |

Ritual/Cultic use

Healing/religious and divinatory rituals |

Nichols (2016) |

| Bradshaw rock art - Kimberly region of Australia | Hallucinatory elements

Psilocybin-induced experiences |

Pettigrew (2011) |

| Sandawe rock art - Kolo region of Eastern Tanzania | Depictions of the mushroom head

Psilocybin use symbol |

Pettigrew (2011) |

Links to further information: psilocybin and history, Mesoamerican, Mazatec, Olmec, Zapotec, Maya, Aztec, Shamanism, Entheogen, Aztec use of entheogens, Bradshaw rock art.

Western science

[edit | edit source]

1950s

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin mushrooms were first introduced into western science by R. Gordon Wasson. Roger Heim later methodically ranked the mushrooms. It was then Albert Hofmann who identified psilocybin and synthesised it (Tylš et al., 2014). See Figure 4.

1960s

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin was used extensively in research of mental disorders and in psychotherapy, a rationale for use being it's promotion of emotional insight by lowering psychological defenses. At this time, psilocybin mushrooms became popular amongst the general public for recreational use (Carhart-Harris et al., 2012).

1970s

[edit | edit source]Given its widespread public use, psilocybin was classed as illegal, and scientific research using human subjects gradually declined (Studerus et al., 2011).

1990s to present

[edit | edit source]Scientific research was revived and remains an area of interest. Given psilocybin is relatively safe to use, well absorbed orally, with effects lasting for a moderately long duration, it has now become one of the most frequently used psychedelics in human studies (Tylš et al., 2014; Studerus et al., 2011).

Quiz 1

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answer and click "Submit".

Emotional effects and the brain

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin is an impressive modulator of serotonergic neurotransmission in various brain structures, which underlies its therapeutic potential. Of particular interest is its effects on emotional face processing, which is implicated in anxiety and affective disorders (Grimm, Kraehenmann, Preller, Seifritz, & Vollenweider, 2018).

Emotion processing networks

[edit | edit source]The amygdala, the centre for emotional processing in the brain lies within the limbic system. See Figure 5. The amygdala is a salience detector specifically linked to the immediate response to emotional face content, processing negative emotions, such as anxiety, fear and anger (Grimm et al., 2018). Psilocybin inhibits the processing of negative emotions in the amygdala, attenuates negative facial expression, and creates bias toward positive emotional responses to negative emotional and social/environmental stimuli, consequently reducing negative emotional responses (Kometer et al., 2012). These are important findings, as should amygdala activity become unbalanced (an indication of impaired emotional processing), psychological disorders may develop, such as depressive and/or anxiety disorders (Swanson, 2018). Psilocybin has shown effective in restoring balance in the amygdala through its antidepressant effects. Recent research demonstrates these antidepressant effects are mediated through modulatory properties on the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, including the amygdala (5-HT2A receptor agonist). See following section "Serotonin". In addition, psilocybin has been found to decrease connectivity between nodes such as the frontal pole or striatum, which are also associated with emotional processing (Grimm et al., 2018).

|

Modulator of major connectivity hubs of the amygdala

Grimm et al., conducted a study evaluating influence of psilocybin on emotional face discrimination. During angry face discrimination, connectivity was decreased between amygdala and striatum. During happy face discrimination, connectivity between amygdala and frontal pole was decreased. During fearful face discrimination, no effect was detected. These results identify psilocybin's effect as a modulator of major connectivity hubs of the amygdala, which is meaningful for future research and assisting to clarify whether such connectivity modifications could predict therapeutic effects in psychiatric patients. |

Serotonin

[edit | edit source]

Serotonin is a significant neurotransmitter within neural networks related to emotion processing, often referred to as the “happy chemical”. Psilocybin produces its effects by acting on neural pathways affected by serotonin. The central hallucinogenic compound of psilocybin acts as an agonist/partial agonist at the 5-hydroxytryptamine (chemical name for serotonin) neurotransmitter. It has especially high affinity for 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A serotonin receptors. Psychological effects of psilocybin are predominantly mediated by 5-HT2A receptor activation, and partially by 5-HT1A receptor modulations (Pokorny, Preller, Kometer, Dziobek, & Vollenweider, 2017). Activation of the 5-HT2A receptors is central in mood regulation and emotional face recognition (Kometer et al., 2012).

Serotonin impacts areas of the brain such as the thalamus relating to sensory perception. Similarly psilocybin acts at 5-HT2A receptors in the thalamus, decreasing thalamic performance, leading to hallucinations. Psilocybin and serotonin share similarities in structural resemblance, explaining the comparable impact on such brain regions. See Figures 6 and 7. These similarities are important in current research into psychological disorders such as depression and/or anxiety which cause abnormalities in sensory perception. Psilocybin is a promising treatment option (Ziabari & Treur, 2019). See following section "Modern uses of psilocybin and research".

Quiz 2

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answer and click "Submit".

Psychological theories of emotion

[edit | edit source]Both biological (emotion results from bodily responses) and cognitive (mental activity forms emotion) perspectives of emotion can help explain how psilocybin affects emotion.

James-Lange theory

[edit | edit source]James-Lange Theory postulates that bodily responses cause emotional experiences following an external stimulus. See Figure 8. This theory, established by psychologists William James and Carl Lange, who shared similar views on the origin of the feeling of emotion. From this perspective, emotion is derived from the perception of bodily states, and the intensity of an emotion experienced, is subject to an individual's awareness of their own bodily signals, described as ‘‘interoceptive awareness’’ and ‘‘visceral perception’’ (Pollatos, Kirsch & Schandry, 2005). This may be consistent with emotional effects of psilocybin, given psilocybin enhances an individual's perception of sense of self and external environment (Dinis-Oliveira, 2017). Psilocybin is a stimulus that causes a physiological response in the body which causes the feeling of emotion, increasing access to emotion and intensifying the feeling of emotion, broadening the overall range of emotions felt. This physiological perspective fits with effects psilocybin has on the body, brain and consequently, feeling of emotion (Swanson, 2018).

Facial feedback hypothesis

[edit | edit source]Facial feedback hypothesis asserts emotion results from facial expressions, suggesting facial expressions provide feedback from the face muscles, which may modulate the subjective experience of emotion (e.g. the act of smiling may bring about joy and happiness). Psilocybin use generally triggers uncontrollable smiling and laughter. This forced facial movement may influence positive emotions and an overall enjoyable experience, consistent with facial feedback hypothesis (Buck, 1980). See Table 2.

Table 2.

Illustration of the process of facial feedback hypothesis

| Event | → | Facial changes | → | Emotion |

Cognitive-mediational theory

[edit | edit source]Cognitive-mediational theory proposed by Richard Lazarus, states that emotion results from appraisal (personal evaluations/interpretations/explanations) of a stimulus, further suggesting emotional responses are mediated by immediate conscious or unconscious appraisals. Appraisal guides cognitive identification of the situation, simultaneously stimulating physiological arousal and emotional experience. Thus, an individual's interpretation of a stimulus (internal or external) will affect emotional response (Lazarus,1993). Psilocybin may have an effect on how people evaluate certain stimuli, specifically intensification of feelings and bodily responses. An individual may evaluate external stimuli in a positive manner, and be more inclined to experience positive emotions, such as increased energy, joy, euphoria, and giddiness. In contrast, if the experience is evaluated as negative, a negative emotional experience could occur (Swanson, 2018). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Illustration of the process of Lazarus' cognitive-mediational theory

| Stimulus | → | Appraisal | → | Physiological arousal

Emotional experience |

Broaden and build theory of positive emotions

[edit | edit source]Broaden and build theory illustrates the form and function of positive emotions. It assumes an individual’s momentary thought–action repertoire is broadened by positive emotions (e.g. interest sparks the urge to explore). In contrast, negative emotions narrow an individual's mindset (e.g. specific action tendencies). Additionally, it is concerned with the consequences of broadened mindsets, thought to result in building personal resources. For example, interest resulting in the urge to explore, results in the individual taking in new information and experiences, ultimately resulting in an expanded version of self (Fredrickson, 2004). This theory is congruent with the emotional effects of psilocybin, a positive experience may begin with feelings of joy and happiness which intensify into euphoria. Similarly, positive emotions such as wonder, catharsis and interest may be experienced, resulting in further exploration of the mind/emotional experience, subsequently building on an individual's sense of self and personal resources. Importantly, a negative experience on psilocybin, eliciting negative emotions such as extreme anxiety, could amplify into an acute psychotic episode (Swanson, 2018).

|

Broaden and build theory/corresponding research indicate positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2004):

Broaden attention and thinking→loosen enduring negative emotional arousal→incite psychological resilience→build consequential personal resources→generate upward spirals towards greater well-being in the future→seed human flourishing. |

Quiz 3

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answer and click "Submit".

Short-term and long-term effects

[edit | edit source]There are many effects associated with the use of psilocybin in clinical and recreational settings.

Short-term effects

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin generates intense feelings and increased access to emotions, broadening the overall spectrum of emotional experience (Swanson, 2018). Subjective effects described include feelings of relaxation, uncontrollable laughter, energy, joy, euphoria, giddiness, visual enhancement (brighter colours), visual disturbances (moving surfaces/waves), and unintentional delusions, including altered perception of reality, faces/images, or vivid hallucinations. See Figure 9. Importantly, subjective effects vary immensely from one use to the next. Research indicates that interpersonal support may affect the experience of the participant. In particular, less adverse psychological effects (e.g. fewer panic reactions/paranoid episodes) are reported when interpersonal support is available. In these circumstances, subjective reports of positive experiences are increased (Van Amsterdam et al., 2011).

Effects of a "bad trip"

A "bad trip" results from a seriously negative experience on psilocybin, which could include severe agitation, confusion, extreme anxiousness, disorientation, and impaired concentration/judgement. The cause of a negative experience is unknown, however many factors are considered contributors, such as quality of the set/setting including, social-cultural environment, psychiatric history/medication, drug sensitivity, substances taken in combination with psilocybin (e.g., alcohol), dosage consumed, method of consumption (orally/intravenously), previous experiences, present state of mind/expectations, and personality (Swanson, 2018). See Table 4. In severe cases, acute psychotic episodes are possible, including strange/frightening images, complete loss of reality/paranoia, possibly leading to serious accidents/injury and potential suicide attempts. Chronic psychotic states may be experienced, in some cases provoking underlying personality disorders and psychosis. Subsequent effects of a bad trip may persist for months, including feelings of faintness, sadness and depression, as well as paranoia (Van Amsterdam et al., 2011).

Table 4.

Interactions and toxicology

| Interactions | Authors | Toxicology | Authors |

| Avoid medications that alter serotonin levels, given psilocybin is a strong serotonin agonist | Passie, Seifert, Schneider, & Emrich (2002) | Low in toxicity, overdose risk and physical/psychological dependence | Studerus et al., 2011 |

| Avoid use of other controlled substances simultaneously/poly drug use | Van Amsterdam et al (2011) | Amongst the safest psychoactive compounds available | Studerus et al., 2011 |

| Alcohol and nicotine are thought to enhance negative effects | Van Amsterdam et al (2011) |

Links to further information: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antidepressants, poly drug use, dimethyltriptamines (DMT's) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAO's), toxicity.

Long-term effects

[edit | edit source]Although there is increasing knowledge of the neural structures involved in acute effects of psilocybin use, long term effects on the human brain are largely unknown. Recent research revealed long term use of psilocybin may result in structural changes in the brain (e.g., anterior cingulate cortex and posterior cingulate cortex) associated with emotion (Polito & Stevenson, 2019). These changes displayed through 5-HT2A agonists, stimulating factors in the brain linked to synaptic plasticity (Nichols, 2016).

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, associated with flashbacks, has been linked to psilocybin use (although more frequently reported after Lysergic acid diethylamide use). This disorder can persist for years after hallucinogen use (Nichols, 2016).

|

Take home message

Psilocybin effects are unpredictable for each individual on any given occasion. Many factors must be considered prior to use. The “set” (individual contributors) and “setting” (social-cultural environment) are important considerations to minimise the risk of a negative experience. Potential short-term and long-term effects of psilocybin use could be unpleasant and serious. Further research must address these effects. |

Quiz 4

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answer and click "Submit".

Modern uses and research

[edit | edit source]Conventional treatment methods involving psychedelics are gaining scientific and medical interest. There has been a resurgence in research pertaining to psychedelics in psychiatry treatment settings during the first two decades of the 21st century. See Figure 10. Treatment methods often combine dosing sessions with some form of psychotherapy (Watts, Day, Krzanowski, Nutt, & Carhart-Harris 2017).

Microdosing

[edit | edit source]Frequent ingestion of modest amounts of psilocybin (0.1-0.5 gm dried mushrooms) is termed 'Microdosing', a contemporary concept gaining popularity both in research and recreationally. People practicing microdosing report minimal adverse effects, whilst detailing benefits to general health and well-being, combined with increased psychological functioning on dosing days with reduced stress and depression levels. Below are participants' comments from a recent study (Polito & Stevenson, 2019).

|

Comments demonstrating experiences of intense emotions

“Microdosing has a significant impact on my ability to get in touch with what is going on deep inside. Although this is not always a pleasant experience, I have a strong feeling that psilocybin helps to reveal what I need to see in myself and the world.” [COMMENT L2] “I was surprised to find myself crying a lot throughout the study despite the fact that I wasn't going through anything typically difficult”. [COMMENT L3] |

Emotional empathy

[edit | edit source]

Emotional empathy has shown to increase from psilocybin effects. Deficits in emotional/affective empathy form part of many psychological disorders (e.g. major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and psychopathy) (Pokorny et al. 2017). Pokorny et al. examined acute effects of psilocybin in healthy individuals on features of empathy and moral decision-making. Implicit and explicit emotional empathy significantly increased in comparison to placebo. These findings are promising in treating mood disorders or psychopathy (by targeting 5-HT2A/1A brain receptors).

Treatment of anxiety and depression disorders

[edit | edit source]Psychedelic therapy has seen a resurgence, the psychedelic experience itself (e.g., mystical-type experience), establishing long-term psychological changes (Griffiths et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016). Watts et al (2017) recently conducted a qualitative study using psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Results revealed change processes, namely connectedness and acceptance of emotion. See participant comments of experiences below. Interestingly, patients reported psilocybin treatment to be more effective than other medications and therapeutic techniques.

|

Psilocybin treatment as bringing connection

[During the dose] "It was like a holiday away from the prison of my brain, I was a ball of energy bouncing around the planet, I felt free, carefree, re-energised". (P8) "I had a clear mind, it lifted the fog of depression. I could see my life, like a light in the tunnel". (P7) |

|

Psilocybin treatment bringing acceptance of emotions

"The blissful feeling got more intense, really overwhelming, the glow grew until I was just that feeling, I had become bliss". (P15) "The beauty and the sadness, I was terrified by the depth of emotions". (P7) "I took away from the experience that I used to get angry about having anxiety, now I think I can have the anxiety, I can just feel it and it will go, I don’t have to have the fear or run away". (P2) "I had lost my ability to grieve and cry. [During the dosing session] I cried and that was a cathartic experience for me, a very welcoming sweet experience". (P19) |

Treatment of anxiety and depression in cancer patients

[edit | edit source]Clinical symptoms of anxiety/depression are often experienced by cancer patients, along with reduced quality of life. Research suggests that psilocybin may reduce symptoms, increasing quality of life (Ross et al., 2016). Griffiths et al. investigated effects of low placebo dose versus high psilocybin dose (randomised/double-blind/cross-over study), 6 month follow up period. Participant moods, attitudes and behaviours were observed (community observers/staff/participants). Results revealed high psilocybin dose generated substantial decreases in depressed mood, anxiety/death anxiety, also increases in quality of life/life meaning, and optimism. Changes were sustained at 6 month follow up, with 80% of participants continuing to display clinically significant decreases in anxiety/depressed mood, together with subjective improvements in attitude towards life and self, mood, relationships and spirituality. 80% of participants experienced greater life satisfaction and overall well-being. Similar studies demonstrate comparable results, suggesting single administration of high psilocybin dose combined with psychotherapy, result in considerable and enduring decreases in depression/anxiety, together with spiritual well-being and overall quality of life. These substantial results are encouraging for future research in establishing generalisation of psilocybin as a safe treatment for psychological distress experienced by people with life-threatening cancer (Griffiths et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016).

Treatment of nicotine addiction or alcoholism

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin has shown to reduce consumption levels of tobacco and alcohol use. Recent research established treatment combining 2 to 3 high doses of psilocybin with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) effective for smoking cessation (Johnson, Garcia-Romeu, & Griffiths, 2017). Johnson et al., observed higher abstinence rates at sic month follow up, when compared to other drug treatments/CBT alone. At 12 month follow up, 67% of participants were smoking abstinent, and 86.7% rated psilocybin experiences as "one of the greatest personally meaningful and spiritually significant experiences of their lives". Research suggests psilocybin combined treatment programs may be successful in advocating long-term smoking abstinence.

Psilocybin treatment for alcohol dependence is in its infancy. Bogenschutz et al., 2015, conducted single-group proof-of-concept study to establish the basis for clinical trials for treatment effects of psilocybin in alcohol-dependent participants. Participants received psilocybin orally in conjunction with motivational enhancement therapy. Abstinence effects were significant (p < 0.05), following psilocybin administration in week 4. Effects persisted at 36 week follow up, and additionally predicted decreased craving/abstinence self efficacy.

Quiz 5

[edit | edit source]Choose the correct answer and click "Submit".

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Psilocybin is a mind altering hallucinogen affecting people’s state of emotion. It brings about intense feelings and increased access to emotions, broadening the overall spectrum of emotional experience, which can be positive (e.g., joy/wonder/interest) or negative (e.g., fear/extreme anxiousness). The complex interaction between psilocybin and emotion was established through its use in ancient cultures. Western science then benefited from its effects in the modelling of psychosis and practice of psychotherapy for depressed patients. More recently, knowledge of the neural structures involved in the effects of psilocybin, and structural changes associated with emotional processing, is of measurable interest for the establishment of treatment regimes for an array of psychological disorders and addictive behaviours. It is however, important to consider potential negative emotional effects of psilocybin use, and minimise the risk of a negative experience. Both biological and cognitive perspectives of emotion can help explain how psilocybin affects emotion, and assist in informing future research.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Emotional effects of psychedelics: What are the emotional effects of psychedelic drugs? (Book chapter, 2019)

- Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and emotion: What is the interaction between LSD and our emotions? (Book chapter, 2017)

- Psilocin (Wikipedia)

- Psychedelic drug (Wikipedia)

- Serotonergic psychedelic (Wikipedia)

- Timothy Leary (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Buck, R. (1980). Nonverbal behavior and the theory of emotion: the facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 38(5), 811.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Leech, R., Williams, T. M., Erritzoe, D., Abbasi, N., Bargiotas, T., ... & Wise, R. G. (2012). Implications for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging study with psilocybin. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 238-244. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103309

Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2017). Metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin: clinical and forensic toxicological relevance. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 49, 84-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03602532.2016.1278228

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359 (1449), 1367-1377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Carducci, M. A., Umbricht, A., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., ... & Klinedinst, M. A. (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1181-1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116675513

Grimm, O., Kraehenmann, R., Preller, K. H., Seifritz, E., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2018). Psilocybin modulates functional connectivity of the amygdala during emotional face discrimination. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(6), 691-700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.03.016

Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 43(1), 55-60. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

Kometer, M., Schmidt, A., Bachmann, R., Studerus, E., Seifritz, E., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2012). Psilocybin Biases Facial Recognition, Goal-Directed Behavior, and Mood State Toward Positive Relative to Negative Emotions Through Different Serotonergic Subreceptors. Society of Biological Psychiatry, 72, 898 –906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.005

Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual review of psychology, 44(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245

Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68, 264–355. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

Passie, T., Seifert, J., Schneider, U., & Emrich, H. M. (2002). The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addiction Biology, 7(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355621021000005937

Pettigrew, J. (2011). Iconography in Bradshawb rock art: breaking the circularity. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 94, 403.417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1444-0938.2011.00648.x

Pokorny, T., Preller, K. H., Kometer, M., Dziobek, I., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2017). Effect of psilocybin on empathy and moral decision-making. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 20 (9), 747-757. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx047

Polito, V., & Stevenson, R. J. (2019). A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. PloS one, 14(2), e0211023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211023

Pollatos, O., Kirsch, W., & Schandry, R. (2005). On the relationship between interoceptive awareness, emotional experience, and brain processes. Cognitive Brain Research, 25 (3), 948-962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.09.019

Ross, S., Bossis, A., Guss, J., Agin-Liebes, G., Malone, T., Cohen, B., ... & Su, Z. (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1165-1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116675512

Studerus, E., Kometer, M., Hasler, F., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2011). Acute, subacute and long-term subjective effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a pooled analysis of experimental studies. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25, 1434–1452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881110382466

Swanson, R. (2018). Unifying Theories of Psychedelic Drug Effects. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, 172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00172

Tylš, F., Páleníček, T., & Horáček, J. (2014). Psilocybin–summary of knowledge and new perspectives. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(3), 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006

Van Amsterdam, J., Opperhuizen, A., & van den Brink, W. (2011). Harm potential of magic mushroom use: a review. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology, 59(3), 423-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006

Watts, R., Day, C., Krzanowski, J., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2017). Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Journal of humanistic psychology, 57(5), 520-564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817709585

Ziabari, S. S. M., & Treur, J. (2019). An Adaptive Cognitive Temporal-Causal Model for Extreme Emotion Extinction Using Psilocybin. In Proc. of the 3rd International Conference on Computational Methods in Systems and Software, CoMeSySo'19.

External links

[edit | edit source]- Can magic mushrooms unlock depression? (TEDx Talks)

- The hidden world of underground psychedelic psychotherapy in Australia (ABC News Article)

- The science of psilocybin and its use to relieve suffering. (TEDMED)

Motivation and emotion/Book/2019 Motivation and emotion/Book/Drugs/Psilocybin