Motivation and emotion/Book/2015/Leaving violent relationship motivation for women

What motivates women to leave violent relationships?

Overview

[edit | edit source]What is domestic violence? Is it physical abuse? Is it just between partners?

Domestic violence (DV) is as any violent or abusive behaviour that occurs between people in an intimate relationship. It is predominantly between spouses or partners but can also be within other intimate or familial relationships. Domestic violence is not just physical abuse, it can also be sexual, emotional, financial and social abuse. Most importantly, the crucial underlying feature is control and violence is perpetrated across these domains to maintain control over the other person (Chang et al., 2010). Data from an Australian Bureau of Statistics survey in 2005 (Domestic Violence Prevention Centre, 2015) revealed that 37.8% of women had experienced a DV episode in the 12 months prior to the questionnaire (see box below for more statistics). Given the history and predominance of violence towards women and the systemic inequality that produces it (Anderson, 1997), this chapter focuses on women. However it is acknowledged that men can also be the victims of domestic violence. There are many complex social and cultural factors that help to determine whether women will leave a violent relationship. These factors include access to safe housing, social support, how the courts and police respond, economic security, cultural background, religious background and the level of violence being perpetrated (Phillips & Vandenbroek, 2014). However psychological and internal barriers also mediate decisions to leave a violent relationship (Shurman & Rodriguez, 2006).

- APPROXIMATELY ONE WOMAN IN AUSTRALIA DIES PER WEEK BECAUSE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

- 58% OF WOMEN WHO HAD EXPERIENCED A VIOLENT INCIDENT IN THE PAST YEAR HAD NOT REPORTED IT TO THE POLICE

- OF THE PHYSICALLY VIOLENT INCIDENTS REPORTED, 62% of WOMEN HAD EXPERIENCED THE LAST ASSAULT AT HOME (Domestic Violence Resource Centre, 2015)

Domestic Violence statistics

- 37.8% of women experienced physical assault in the 12 months before being surveyed.

- The perpetrator was a current or previous male partner. 34.4% said the perpetrator was a male family member or friend.

- 33.3% of women had experienced physical violence since the age of 15.

- 19.1% of women had experienced sexual violence since the age of 15.

- 73.7% of men who said they had experienced physical violence in the 12 months before the survey said that the perpetrator was a male (ABA, 2005).

GLOBAL STATISTICS REVEAL THAT ONE IN THREE WOMEN WORLDWIDE EXPERIENCE VIOLENCE FROM A PARTNER (DVRC, 2015)

But first why is domestic violence so prevalent? The history of gender inequality puts this into context

History

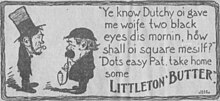

[edit | edit source]The "rule of thumb" is a common saying in Western culture that is thought to have had its origins in a ruling made in 1782 in England, allowing a man to beat his wife with a stick as long as it is was no thicker than his thumb (see Figure 1). The origins of the saying have been disputed more recently (Davidson, 1977). However, British common law did state that men were able to chastise a woman as you might chastise a child or a servant. Legally women were seen as a single entity with their husband and as such were completely subsumed by the husband's identity. This gave the husband a right, and in some cases duty, to discipline his wife, as her actions were a reflection on him. Although laws regarding violence against women have changed in Western cultures more recently, residual beliefs and practices continue in part because violence towards women has been a normalised and legally condoned practice for centuries (Davidson, 1977).

During most of the twentieth century, up until the 1970s, psychological explanations for women being in violent relationships were explained by Freudian theory. Women were seen as masochistic and to derive both pleasure and a need for punishment from the violence they were receiving (Anderson & Saunders, 2003). This was the prevailing psychological perspective and it highlights some of the entrenched nature of blaming the victim instead of the perpetrator (Caplan, 1993). In 1987, masochistic personality disorder was proposed as a disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM), third edition. Many psychologists objected to its inclusion and the disorder did not make it into the DSM. The objection was made on two grounds: firstly that there was no research evidence to support the notion that people enjoyed or needed misery and suffering and secondly that the diagnosis could be used to justify victim blaming of women for their own circumstances, including domestic violence perpetrated against them (Caplan, 1993). These objections were part of a broader feminist movement questioning women's societal position in general.

In the 1970s, the feminist movement challenged psychodynamic notions, arguing that social conditions and economic constraints prevented women from leaving violent relationships. Institutionalised sexism and legal inequality became the site for the struggle to address domestic violence (Anderson, 1997; Anderson & Saunders, 2003). The women’s liberation movement set up the first women’s refuge in Australia for women and children escaping DV. Elsie Women's Refuge was established in Glebe in 1974 and this gave women and children somewhere to go that was safe from violence (NSW Women's Refuge Movement).

Although the social, structural and legal obstacles facing women escaping DV began to change, women continue to remain in unsafe situations. There are certainly not enough support services to deal with all the women who need assistance (Phillips & Vandenbroek, 2014), but this is not enough to explain why, when two women with very similar backgrounds and relationship history are faced with a choice of leaving a violent situation, one does and one does not. Research has begun to look at not only the social barriers facing women, but some of the internal barriers. Motivational psychological theory has been used to explore these internal barriers and what might motivate someone to stay or to leave a violent relationship.

What motivates one woman to leave a violent relationship and another to stay?

Motivational Theories

[edit | edit source]Motivational theories are explanations for behaviour. Why do we do the things we do? What propels us to act or feel or need certain things? Motivation can be physiological but there are a range of other behaviours humans perform that are not necessary for survival. What makes one person motivated towards a particular goal and not another? (Reeve, 2015). In context of this chapter what motivates some women to leave a violent relationship but not others? Motivational theories such as learned helplessness and the Transtheoretical Model (TM) help to explain why this discrepancy in motivation to leave a violent relationship may exist.

Learned Helplessness

[edit | edit source]Learned helplessness theory is based on Seligman's (1976) lab experiments with dogs. The dogs were faced with a series of electric shocks with nowhere to escape and after a number of experiences in this condition the dogs were given the opportunity to escape from the shock. The majority didn't, leading to the the assumption that the dogs believed that whatever action they took it would not impact on the situation. The dogs experienced what Seligman and Maier (1976) termed learned helplessness, a lack of perceived control over uncontrollable circumstances that led to helplessness and a reduced ability to act (Seligman & Maier, 1976).

This theory has been applied to behaviour observed in humans. Learned helplessness has been used to explain why some people who have no control in initially uncontrollable circumstances will develop an inability to act in, or attempt to change, future situations. This helplessness can also be generalised to other situations. Three deficits have been identified as resulting from having no perceived control in these conditions; motivational, cognitive and emotional (Abramason, Seligman & Teasedale,1978).

- Motivational: Voluntary responses become suppressed if outcomes are seen as uncontrollable

- Cognitive: A person expects that outcomes are uncontrollable

- Emotional: Depression ensues if a person learns that outcomes are uncontrollable

|

"Eventually, I withdrew and kept everything to myself and I even started to get depressed, at one time I didn’t know who I was anymore" Sallie's story (DCRCV, 2015). "… The more I stayed with him the more it destroyed my self esteem. I convinced myself that I was useless, I was dumb, I was a bitch, whatever he had been calling me. With that sort of brainwashing I became very dependent on him, thinking that there’s no way I would survive without him. I thought that only he would take me because I am such a horrible person". Donna's Story (DCRCV, 2015). |

When traumatic events occur over time with a sense of uncontrollability, learned helplessness can eventuate. Theorists have linked the learned helplessness phenomenon with domestic violence situations, as these are generally situations with prolonged exposure to trauma and little perceived or actual immediate control (Walker, 2009). It has been argued that women in DV situations will try a number of times to effect change, but when this has little or no effect on the situation and the violence continues, learned helplessness may result (Walker, 2009). Women may experience a suppression of voluntary responses and feel unable to leave a violent situation (motivational deficit), expect that outcomes are uncontrollable and that they have no choice but to remain in the situation (cognitive deficit) and suffer from depression which can consolidate helplessness (emotional deficit). Clearly this has implications for whether women are motivated or not to leave a violent relationship. The experience of learned helplessness and the associated depression may also play a role in movement through the stages of the Transtheoretical Model.

Transtheoretical Model

[edit | edit source]The Transtheoretical Model (TM) was proposed by Procheska and DiClemente (1984) and is a model for intentional behavioural change. It is a biopsychosocial model that has been applied to a variety of issues such as smoking and weight loss and posits that people move through behavioural change in stages. The TM model has five stages as follows:

- Pre-contemplation: At this stage the person is unaware that there is a problem

- Contemplation: The person begins to contemplate change and an intention is formed

- Preparation: At this stage the intention to act is imminent

- Action: The person takes action

- Maintenance: The person works hard to prevent relapse and maintain the changed behaviour

Although conceptualised as a linear process people can go back and forth in the stages of the TM (Procheska & DiClemente, 1984).

Central to the TM is self-efficacy. This is a person's belief in their ability to effect the change they are desiring to make. This includes the beginnings of managing a new behaviour, the degree of effort a person will be able to put in to coping, and the persistence of the desired behaviour, despite setbacks and hardships (Bandura, 1977). According to Prochaska and DiClemente (1984) in the early stages of the TM self-efficacy tends to be lower as a person's behaviour fluctuates and can return to the older entrenched behaviours. In the later stages such as the action and maintenance stages, self efficacy increases as the person sees the gains they have made. This increases the chances of the behaviour being modified successfully, which in turn increases self-efficacy.

Transtheoretical Model and the Motivation to Leave a Violent Relationship

[edit | edit source]The TM has been utilised by theorists examining women's motivation to leave a violent relationship. Burke, Gielen, McDonnell, O'Campo and Maman (2001) propose that the TM is a useful framework to understand the process women go through when thinking about and leaving domestic violence. Research found that the stages of the TM model fit well with the stages that women who had left DV relationships were reporting.

- During the pre-contemplation stage the woman may not be aware that the abuse is a problem.

- As the woman enters the contemplation stage she becomes aware that there is a problem. This is usually brought about by a specific event that allows the woman to name the abuse for what it is.

- The move from the contemplation stage to the preparation stage involves the evaluation of the benefits and losses of leaving or staying in the relationship, including safety and financial concerns and children's needs.

- The action stage is characterised by women performing actions to stop the violence such as going to a women's refuge, going to the police, or trying to secure a Domestic Violence Order.

- During the maintenance stage the woman is striving to stay away from the abusive relationship and start a new life.

(Burke et al., 2001).

Knowledge of these stages is useful for refuge workers, counsellors and clinicians who work with women leaving violent relationships, as they can select interventions for the various different stages of the process. It is clear that an intervention may be appropriate at one stage of the process but not at another (Shurman & Rodriguez, 2006).

Shurman and Rodriguez (2006) maintain that the ability to move through the five stages of change are predicted by certain affective and cognitive components.

Cognitive

[edit | edit source]The two cognitive variables predicting movement through the five stages of the TM are:

Attribution style

Attribution style refers to the way in which the woman perceives and explains why and how the violence and abuse is happening. Based on attributional theory, causes and outcomes are perceived as either stable or unstable, external or internal, and controllable or uncontrollable (Wiener, 1985). According to some research looking at DV and attribution style, a woman may need an external attributional style in relation to the abusive partner to have the impetus to leave the relationship. The blame for the violence needs to be placed onto the abusive partner rather than onto herself. This is particularly important in the movement between the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages and may also be necessary for maintenance of the behavioural change (Shurman & Rodriguez, 2006).

This perspective is at odds with other research in the area that argues that women tend to need an internal attribution style to leave a violent relationship. According to Kim and Gray's study (2008), women who stay in domestic violent situations are more likely to have an external attribution style. The authors found that women who were in non-abusive relationships tended to have a higher internal attribution style generally, whereas women in abusive relationships had an external attribution style. Women with a higher internal attribution style who found themselves in an abusive relationship, were more likely to leave because of this psychological factor. This result was consistent with prior studies examined by Kim and Gray (2008). In Clements, Sabourin and Spiby's (2004) research, the authors found that high perceived control and self-blame were factors that may contribute separately to dissatisfaction with a violent relationship. It is conceivable then that someone may have an internal attribution style without blaming themself for the abuse that is happening.

Attachment style

Attachment style is based on Bowlby's attachment theory, but uses the extended theory of adult attachment developed by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991). Four styles of attachment are identified in adults: secure, preoccupied, dismissing, and fearful (Batholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Of these four styles Shurman and Rodriguez (2006) maintain that the preoccupied and fearful attachment styles are prevalent in the attachment styles of women in violent relationships (see box below for more information on these styles). In a sample of 63 women who had left violent relationships recently, Henderson, Bartholomew and Dutton (1997) found that these attachment styles were two to three times higher than in the general population. The preoccupied attachment style accounted for 53% of the women sampled and the fearful style accounted for 35%.

In the context of the TM, the preoccupied attachment style has been found to be detrimental to women in the first three stages, as they cycle back and forth between feelings of neediness for, and rejection of, the relationship. However the preoccupied attachment style was also found to be a strong predictor of a woman staying away from a violent relationship during the maintenance stage of the TM. The preoccupation with the abusive ex-partner was suggested to be a strong predictor as it allowed for ongoing cognitive appraisal of the abuse and violence. This process enabled the woman to strengthen her decision to stay away from the relationship (Shurman & Rodriguez, 2006).

The most frequently seen attachment style in women in abusive relationships is the preoccupied style. This style requires high levels of approval from partners and significant others and the person is dependent on these attachments for self esteem and identity. The style is characterised by a negative view of the self and a positive view of others, hence the dependence on others for validation (Anderson et al., 1997; Shurman & Rodriguez, 2006).

The second most frequent attachment style reported in abusive relationships is the fearful style. This style is avoidant of relationships and fears rejection from partners and significant others. The style is characterised by a negative view of the self and a negative view of others. This style was found to have less impact on a woman's readiness to leave a violent relationship than a preoccupied style (Anderson et al., 1997: Shurman & Rodriguez, 2006).

Affect

[edit | edit source]The four affective variables, based on prior studies (Burke et al. 2001) and discussed by Shurman and Rodriguez (2006), as helping to predict movement through the five stages of the TM are:

- Depression: depression is negatively correlated with the confidence to leave a violent relationship and positively correlated with remaining in the situation

- Hopelessness: hopelessness is negatively correlated with the confidence to leave a violent relationship positively correlated with remaining in the situation

- Anxiety: Generalised Anxiety Disorder is found to be three times higher in women in DV relationships, however it could be that the abuse causes the depression itself

- Anger: anger has been found to motivate change and move women forward toward the goal of leaving a violent relationship

Shurman and Rodriguez"s study (2006) found that these four emotions predicted movement through the five TM stages, however it was overall emotional arousal (combined with a preoccupied attachment style) rather than one specific emotion that determined readiness to leave a violent situation. Motivation was dependent on experiencing internalising emotions, such as depression and anxiety, as well as the externalising emotion of anger to stimulate change. In the process of initiating leaving and staying away from a violent relationship, internalising and externalising emotional experiences were found to be compatible.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]External social conditions such as resources, support, and attitudes, all have an effect on the possibilities, expectations and beliefs in a woman's motivation and readiness to leave a violent relationship. However, this motivation will be mediated by individual psychological factors. The two are interrelated{. The social services and support available will mediate whether a woman develops learned helplessness: if adequate housing, and economic and emotional support exist, there is a greater possibility of having a sense of psychological control over what seems to be an uncontrollable circumstance. Conversely, learned helplessness, attribution, and attachment style, may complicate motivational impetus or attempts to leave a violent relationship, even if services and support are available. Both external and internal barriers need to be understood when working with women in violent relationships.

When considering motivational theories such as learned helplessness and the transtheoretical model, there are clear implications for practitioners working with women in domestic violent relationships. Intervening appropriately in the various stages of the TM is important as a woman may not be ready for certain information or strategies that may be entirely necessary and appropriate at a later stage. This means tailoring interventions to suit particular stages. An awareness of learned helplessness also allows practitioners to understand firstly, why a woman may not be able to leave a situation immediately and secondly, how interventions can be structured to counteract the negative impact of learned helplessness. Contextualising depression as a potential result of learned helplessness, rather than a biological issue, also prevents women being pathologised as the problem to be fixed in the violent relationship.This broadens the understanding that individual experience is tied inextricably to external situations and social experience.

Although the transtheoretical model and the learned helplessness model do not fully explain the complexity of of the motivation for women to leave a violent relationship, they do contribute important knowledge of the barriers and potential pathways for women to lead a life free from domestic violence.

See Also

[edit | edit source]Depression and Motivation (2010)

Learned Helplessness (2010)

Perceived Control and Emotion (2014)

Attributions and Motivation (2014)

References

[edit | edit source]Anderson, D.K. & Saunders, D.G. (2003). Leaving an Abusive partner: An Empirical Review of Predictors, the Process of Leaving, and Psychological Well-Being. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,4 (2), 163-191. doi: 10.1177/1524838002250769.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioural Change. Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191-215.

Bartholomew, K. & Horowitz, L.M. (1991). Attachment Styles Among Adults: A Test of a Four-Category Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 (2), 226-244.

Burke, J. G.; Denison, J. A.; Gielen, A. C., McDonnell, K.A. & O'Campo, P. (2004). Ending Intimate Partner Violence: An Application of the Transtheoretical Model. American Journal of Health behaviour, 28 (2), 122-133.

Caplan, P.J. (2005). The Myth of Women’s Masochism. Lincoln, NE.: iUniverse Inc.

Chang, J. C. Dado, D. Hawker, L. Cluss, P. A. Buranosky, R. Slagel, L. McNeil, M. & Hudson Scholle, S. (2010). Understanding Turning Points in Intimate Partner Violence: Factors and Circumstances Leading Women Victims Toward Change. Journal of Women's Health, 19(2), 251-259. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1568.

Clements, C. M., Sabourin, C. M. & Spiby, L. (2004). Dysphoria and Hopelessness Following Battering: The Role of Perceived Control, Coping, and Self-Esteem, Journal of Family Violence, 19(1), 25-36.

Davidson, T. (1977). Wife Beating: A Recurring Phenomenon throughout History. In Maria Roy (ed.), Battered Women: A Psychosociological Study of Domestic violence. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

NSW Women's Refuge Movement. Retrieved from Domestic Violence NSW web site: http://www.dvnsw.org.au/

Domestic Violence Prevention Centre Gold Coast Inc. (2015). Domestic violence statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.domesticviolence.com.au/pages/domestic-violence-statistics.php.

Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria. Facts on Family Violence 2015. Living in fear. Retrieved from: http://www.dvrcv.org.au/knowlege-centre/our-publications/poster/facts-family-violence-2015.

Henderson, A. J. Z., Bartholomew K., & Dutton, D. G. (1997). He Loves Me; He Loves Me Not: Attachment and Separation Resolution of Abused Women. Journal of Family Violence, 12 (2), 169-191.

Kim, J. & Gray, K. A. (2009) Leave or Stay? Battered Women’s Decision After Intimate Partner Violence. The University of South Carolina Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23 (10), 1465-1482.

Phillips, J. & Vandenbroek, P. (2014). Domestic, family and sexual violence in Australia: an overview of the issues (Research Paper Series 2014-2015). Canberra, ACT: Parliamentary Library.

Prochaska, J.O. & DiClemente, C.C. (2003). The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing the Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Homeward, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Reeve, J. (2015). Understanding motivation and emotion (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Seligman, M. E. & Maier, S. F. (1976). Learned Helplessness: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology 105 (1), 3-46. http://dx.doi.org?10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3

Shurman, L.A. & Rodriguez, C. M. (2006). Cognitive-Affective predictors of Women’s Readiness to End Domestic Violence relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21 (11), 1417-1439.

Walker, L. (2009). The Battered Women's Syndrome. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Wiener, B. (1985). An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion Psychological Review, 92 (4), 548-573.

External Links

[edit | edit source]VIDEO: TED talk on domestic violence (Leslie Morgan Steiner)

VIDEO: TED talk on violence against women as a men's issue (Jackson Katz)

VIDEO: Description of Learned Helplessness (video from 1952 series "Talking Sense")