Motivation and emotion/Book/2015/Exercise motivation in people living with dementia

How can motivation to exercise be developed in people living with dementia?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Felicity aged 94 was diagnosed with dementia three years ago. During her life she had enjoyed numerous activities including reading, playing the piano and card games. Felicity had been living in a mental adjustment unit for a period of two years. During this time staff experienced trouble interacting with her and she usually wanted to keep to herself. She was often upset when staff members tried to help her with daily activities. However, through interventions staff were able to focus upon her current abilities and interests and create a more enjoyable environment for Felicity and her carers. One type of intervention was exercise which also provided her with a number of physical health, cognitive, mental health benefits and social opportunities. This new approach to caring for Felicity improved her overall quality of life (Khoo, Schaik & McKenna, 2014; Teitelman, Raber & Watts, 2010).

Caring for individuals living with dementia can be a difficult task for both families and staff. Stories like Felicity's are common. The degenerative nature of the disease impacted greatly upon her feelings of independence. Participation in exercise is one type of intervention that can provide a number of positive outcomes for individuals with dementia and their carers. However, there are issues surrounding lack of motivation in individuals with this condition (Williams, 2005). Someone in your family may have been diagnosed with dementia, maybe you work in a setting caring for individuals with this condition or want to improve your own cognitive functioning. This chapter aims to answer the following questions:

- How can motivation to exercise be developed in people living with dementia?

- What are the benefits of exercise for people with this condition?

- What barriers can exist when attempting to motivate this exercise?

- Can exercise act as a protective factor regarding development of dementia?

What is dementia?

[edit | edit source]

Dementia is characterised by cognitive decline in individuals eventually leading to dependence regarding daily functioning (see Figure 1). Numerous types of dementia exist based on underlying factors causing the decline (Cunningham, McGuinness, Herron & Passmore, 2015). Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia make up the majority of diagnoses (Cunningham et al., 2015). Cognitive decline occurs across five domains: executive function, language, memory, visuospacial, behaviour and personality. In 2009 a prediction was made that by the year 2050 the number of Australian’s living with dementia would increase by four fold from 245,000 to 1.13 million (Brodaty & Cummings, 2010). The prevalence of dementia has been found to be even higher in Aboriginal Australians (Smith et al., 2008). The growing number of people with this condition is putting strain on health care systems and families involved (Brodaty & Cumming, 2010). The increasing number of diagnoses highlights the need for focus upon interventions to improve the functioning and lives of individuals with this condition.

Developing motivation to exercise

[edit | edit source]A number of theories exist relating to exercise motivation in people living with dementia. Focus will be placed upon two theories and one model regarding care (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of theories discussed throughout the chapter

| Theory | Description |

|---|---|

| Social learning theory | Focus on motivation through observational learning. |

| Self-efficacy | Increasing self-efficacy through challenging exercise, this in turn can motivate participation. |

| Person centred care | Creating motivation through humanising individuals with dementia. |

It is important to discuss these theories to gain a better understanding of how motivation to exercise can be developed in people living with dementia. The key components of these theories will be addressed along with research and practical applications.The theories discussed are all based on different principles however, overlap exists among the content covered. Rather than viewing them as separate attempt to understand how they work together and compliment one another.

Social learning theory

[edit | edit source]Social learning theory is applicable to developing motivation to exercise in people living with dementia. Due to the cognitive decline that occurs in individuals with this condition exercise motivation and participation must be undertaken using approaches that do not rely greatly on cognitive ability (Teri, Logsdon & McCurry, 2008). This statement may seem counter intuitive as Albert Bandura developed this theory to highlight the importance of cognition and its influence on behaviour (Grusec, 1992). However, Teri and colleagues (2008) employed elements of this theory during development of strategies to motivate exercise in people with dementia. The strategies developed by Teri et al. (2008) are known as the Seattle Protocols and were originally created to aid treating depression in people with dementia. The Seattle Protocols utilise a concept of social learning theory known as observational learning. Observational learning involves

four stages which can be applied to the current discussion:

- The individual with dementia needs to pay attention to a behaviour in this case exercise that is being modelled. Modeling involves another individual such as a staff or family member performing the exercise behaviour.

- As the individual with dementia is watching the exercise movements this information needs to be retained. This can be achieved through implicit learning, refer to box below.

- After viewing an exercise the individual with dementia can attempt to replicate it or a similar version of the movement.

- To continue exercise there must be motivation for the individual. This can be provided through feedback, goal setting, self-monitoring, reinforcement or implicit learning. The exercise must be made fun and interesting so that individuals want to continue to participate (Grusec, 1992; Teri et al., 2008).

The Seattle Protocols involve breaking exercise down into steps and once an individual has mastered a movement they move onto the next one. The person instructing may use music or sing songs to cue behaviour. Eventually the exercise can become a chain of behaviours and individuals may have the ability to remember exercise movements and their order (Khoo et al., 2014). This again reflects implicit learning, individuals with dementia may not recall previous sessions of exercise but can have the ability to form procedural memories (Khoo et al., 2014).

|

Implicit learning Implicit learning may contribute to the ability of individuals with dementia to remember exercise routines. This process may also act as a reinforcer, further increasing the likelihood of exercise occurring in the future. Yao et al. (2008) used a positive emotion-motivated Tai Chi (refer to Figure 2) intervention to explore program adherence. This intervention was based on the knowledge that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease can have the ability to create new implicit memories (Budson & Price, 2005). This means that the ability to unconsciously retain procedural memories such as Tai Chi movements may exist and improvement could be possible (Khoo et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2008). Yao et al. (2008) add that emotional stimulation may act as a positive reinforcer for implicit learning and motivate individuals to participate. Researchers conducted a survey to investigate what activities participants enjoyed most. Results indicated they enjoyed spending time with family over other activities. Family participation in the Tai Chi sessions was then implemented as a reward. Results indicated it was possible to motivate some individuals with dementia to exercise and continue over a 16-week period. This study shows that although individuals diagnosed with dementia may experience cognitive decline their remaining cognitive abilities can be utilised. |

Does observational learning develop motivation?

[edit | edit source]Seattle Protocols are based around observational learning which falls under Bandura's social learning theory. Research has been conducted to assess the efficacy of these protocols across a number of areas. A randomised controlled trial conducted by Kukull et al. (2003) included 153 community residing individuals with a diagnosis of dementia. Participants were randomly assigned to either an exercise condition based on the Seattle Protocols or a routine medical care condition. Participants attended sessions once a week for a period of 24 months. Results indicated that those in the exercise condition had significantly better scores for physical functioning. Compared with baseline scores those in the exercise condition displayed significant improvement on depression scores. This study demonstrates that interventions involving observational learning can motivate exercise.

Test yourself!

|

Self-efficacy theory

[edit | edit source]Self-efficacy theory can also be applied to the development of exercise motivation in people living with dementia. Self-efficacy as defined by Bandura 1997 (as cited in Olsen, Telenius, Engedal & Bergland, 2015) is an individuals views regarding their ability to master behaviours, high self-efficacy is related to feelings of control and empowerment. Bandura's interest in self-efficacy originated during investigations into how participant modeling impacted upon recovery from phobic disorders. It became apparent to Bandura that an individuals beliefs regarding their own abilities was formed through changes in their behaviour (Grusec, 1992). This relates back to the original case study which highlighted the diminished sense of independence which can occur in individuals with dementia. Self-efficacy is formed through four sources of feedback:

- Mastery experiences in one's own life, this could be achieved through performing an exercise movement

- Vicarious experiences, such as watching another individual with dementia perform exercise

- Verbal persuasion from others, words of encouragement from staff or family members. This video provides an excellent example of how carers can provide verbal persuasion.

- physiological and affective states, exercise may make individuals feel stronger or more vital (Olsen et al., 2015).

Self-efficacy and motivation

[edit | edit source]Research conducted by Olsen et al. (2015) used qualitative methods to investigate exercise motivation and self-efficacy in people living with dementia. The study involved eight older adults who had been diagnosed with mild-to-moderate dementia. Over a ten week period the participants took part in a high-intensity exercise program and data was collected through semi-structured interviews. The data was then analysed in relation to Bandura's self-efficacy theory. Results from the study indicated that exercise may facilitate an increase in self-efficacy. Participants found the exercise gave them feelings of achievement, this links back to mastery experiences. Bandura 1977 (as cited in Olsen et al., 2015) indicated that mastery experiences have the most impact on an individual's self-efficacy. Although the exercise was high-intensity it was not too difficult and the participants noted that the challenges made the exercise more enjoyable. An achievable level of challenge is crucial to participants having mastery experiences (Olsen et al., 2015).

Exercise is also related to the release of endorphins, which can improve mood and are related to source four, physiological states. Participants also reported events of vicarious experience and verbal persuasion. These findings related back to the story of Felicity, these results demonstrate how exercise may improve motivation, social interaction and feelings of independence. Participant statements in the box below provide an example of how psychological theory can help individuals lead more effective motivational lives. See the last paragraph of self-efficacy for an example of research which demonstrated that high self-efficacy is not always related to exercise motivation. This research highlights the importance of optimally challenging activities to maintain motivation (Olsen et al., 2015).

|

Participant statements “It feels good to exert yourself. Maybe I should have pushed myself even harder. We who are old may not be used to it. There is no harm in exerting oneself. Maybe it is more fun that way. It will lead to more energy and optimism." “I thought that the exercises were challenging. I was somewhat proud of myself for making it. Obviously, you should be motivated and experience capability. We got the feeling: we can do this." “I felt more like a normal person. I was happier. I had more energy to engage in conversations and I also became more positive towards other people.” (Olsen et al., 2015) |

Qualitative research

[edit | edit source]Qualitative research such as the study by Olsen et al. (2015) does not provide causal links however, it has become more common when conducting investigations involving people diagnosed with dementia. Researchers note this method provides validation to the participants (Olsen et al., 2015). There is debate surrounding the quality of data provided by individuals with cognitive decline. Vingerhoets, Baalen, Sixma and Lange (2011) conducted a literature review focused on including individuals with dementia in research. The authors concluded that individuals with mild-to-moderate dementia who had language skills can provide clear and insightful information about their experiences. This is one reason participant quotes are included in this chapter, it highlights that their experiences are important.

Test yourself!

|

Person centred care

[edit | edit source]Person centred care (PCC) was developed by Tom Kitwood (1997). This model was created as a reaction to the depersonalisation of individuals with a disability. The main focus of the theory is to bring humanisation into caring for those living with dementia (Kitwood, 1997). PCC aims to motivate individuals through the reversal of detrimental messages regarding their functioning. Research conducted by Teitelman et al. (2010) used the principles of PCC to create motivating social environments for individuals living with dementia. Researchers found that using PCC was linked to motivation to participate in activities while lack of PCC was related to poor involvement. These findings could be applied to improving motivation to participate in an exercise program. This study was limited by its small sample size of eight participants. It also employed qualitative methods which provide a good basis for research however, later studies should attempt to conduct randomised controlled trials to further investigate the efficacy of PPC compared with other approaches. Future investigations should also aim to include individuals who are living at home to increase generalisability.

Benefits of exercise

[edit | edit source]A number of positive outcomes exist for individuals living with dementia who participate in exercise. These outcomes reflect the importance of developing motivation to exercise in people living with dementia.

Physical health

[edit | edit source]

Increase in physical health is one positive outcome that can occur from participating in exercise, this is an important aspect of symptom management. Research conducted by Henwood and colleagues (2015) involved participation of those with dementia in aquatic based exercise.

A significant improvement was found in the participant’s handgrip strength. Heyn and colleagues (2004) conducted a meta-analysis which included 30 randomised controlled trials. The results indicated that 1142 of the participants had significantly improved combined outcomes in physical functioning compared with the 1119 controls. Specific areas of improvement included flexibility, strength, cardiovascular and physical function. These studies show that improved physical functioning can be an outcome of exercise in older adults with dementia. However, Henwood et al. (2015) noted that decline in program participation needs to be addressed. This could be done through implementing aspects of the theories discussed into exercise programs to maintain motivation.

Cognitive function

[edit | edit source]Participation in exercise can also enhance cognition in people living with dementia. Farina, Rusted and Tabet (2014) conducted a meta-analysis of six studies which used randomised controlled trials. The authors found overall exercise could decrease the speed of cognitive decline.

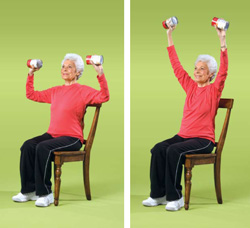

Mental health

[edit | edit source]Psychological well-being is another outcome that exercise may improve. Khoo and collegues (2014) created the Happy Antics program as part of research aimed at investigating the psychological impact of exercise on people with dementia. The program was one 45-minute session per week over a period of six weeks. Activities combined exercise with aspects of yoga, meditation, dance and mindfulness. The program was constructed around movements that could be done while in a chair (see Figure 3) with optional short duration standing. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect qualitative data about the sessions from patients and caregivers. Themes that arose included: relaxation, fun, learning, social opportunities, reduced pain and staying active. Individuals involved in the program made the following statements:

|

Participant statements “It's making me do something I wouldn't do at home, and carry out movements I can manage,” Mary, person with dementia. “I am not normally a sociable person but I like this group and the people in it. I can socialize and talk about my memory problems. I feel good,” Jon, person with dementia. (Khoo et al., 2014) |

Results indicated numerous positive outcomes such as mastery experiences. Khoo et al. (2014) acknowledge a limitation regarding their sample size of six. However, the study provides promising preliminary results and the program could be administered to larger groups in the future. Later research could collect quantitative measures to further understand the benefits. Measures could cover physical and psychological well-being, improvements in cognition and levels of motivation to participate.

Barriers to performing exercise

[edit | edit source]A number of barriers exist in relation to older adults with dementia participating in exercise.

- Falls are an important consideration when exercise is initiated in people living with dementia. In aged care facilities it is estimated 50% of individuals suffer a fall during 12 months, this figure rises to 70-80% in people diagnosed with dementia (Haralambous et al., 2010). Falls can be addressed through conducting exercise from a sitting position. Exercise can also be conducted successfully in a swimming pool with people that have dementia (Henwood et al., 2015).

- It is common for individuals with dementia to feel insecure (James, Blomberg & Kihlgren, 2014). Olsen et al. (2015) demonstrated that interaction with staff during exercise can ease insecurities. Participants reacted well when their instructor displayed knowledge regarding the abilities of older adults and altered the program to suit their needs. This also relates back to the motivational aspect of observational learning.

- Individuals with dementia living in care are often not involved in activities that utilised their abilities (Wood, Womack & Hooper, 2009). Olsen et al. (2015) discuss environments that do not provide encouragement and opportunity for participation in exercise as a barrier. The authors add this could have a detrimental impact on self-efficacy whereas an environment that provides opportunities may have a positive impact.

- Olsen et al. (2015) highlight that dependence on staff or family should not been seen as a barrier towards older adults participating in exercise. A need for help does not necessarily relate to lower levels of self-efficacy.

Exercise as a protective factor

[edit | edit source]Exercise throughout life may act as a protective factor against dementia in older age. Graff-Radford (2011) conducted a literature review reasoning that, in order to improve later life, investigations should be aimed at exploring factors related to decreased cognition. The authors reviewed many different types of research including correlational, randomised controlled trials and animal studies. Findings indicated aerobic exercise may act as a protective factor. However, Graff-Radford (2011) highlights the need for prospective blinded investigations to provide further evidence.

Longitudinal research by Andel et al. (2008) aimed to investigate the relationship between midlife exercise and dementia in later life. Results indicated that light to moderate exercise was related to reduced instances of a dementia diagnosis when other variables such as sex and education were controlled for. Interestingly the same impact was not seen in those who participated in more intense exercise. A limitation of this study is the use of self-report. Researchers suggest that objective measures over time could be used to address this in a similar study. The current body of research suggests that light to moderate aerobic exercise may be the most effective for improving cognition and may act as a protective factor against cognitive decline. It is important to note this is a relatively new area of research and there is still much more to discover. This TEDx Talk by Wendy Suzuki describes the benefits of aerobic exercise as a protective factor and relates it to neuroplasticity and creativity.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The aim of this chapter was to increase understanding of how motivation to exercise can be developed in individuals living with dementia. The key concepts of observational learning, self-efficacy theory and PCC were described. The two theories and PCC were then related to relevant research which demonstrated their ability to motivate exercise in individuals with dementia. Additionally this research included a number of other positive outcomes which were elaborated upon through discussion of exercise benefits. Practical applications of the research were provided through linking information back to the initial case study. A number of barriers specific to individuals with this condition were also addressed. The chapter finished with information regarding the ability of exercise to act as a protective factor against cognitive decline.

Take home message

- Numerous interventions exist based on theory and research which promote exercise and fun for individuals with dementia.

- People with this condition can provide valid insight into their experiences and preference for activities. Focus should more often be placed upon what they can achieve.

- Individuals with dementia can lead active and healthy lifestyles. Exercise in these individuals means a lot more than just increasing fitness.

- A number of barriers can exist when attempting to implement an exercise program. Many of these can be addressed through increased support.

- Current research suggests that aerobic exercise throughout the lifespan may act as a protective factor against cognitive decline.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Alzheimer's and motivation

- Motivating the elderly to exercise

- Exercise motivation

- Dementia care motivation

References

[edit | edit source]Brodaty, H., & Cumming, A. (2010). Dementia services in Australia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25, 887-895. doi:10.1002/gps.2587

Budson, A. E., & Price, B. H. (2005). Memory dysfunction. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(7), 692-699. doi: 10.1002/9781444344110

Cunningham, E. L., McGuinness, B., Herron, B., & Passmore, A. P. (2015). dementia. The Ulster Medical Journal, 84(2), 79-87. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4488926/

Farina, N., Rusted, J., & Tabet, N. (2014). The effect of exercise interventions on cognitive outcome in alzheimer's disease: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(1), 9-18. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001385

Graff-Radford, N. R. (2011). Can aerobic exercise protect against dementia? Alzheimer's Research and Therapy, 3(1), 6-6. doi:10.1186/alzrt65

Grusec, J. E. (1992). Social learning theory and developmental psychology: The legacies of robert sears and albert bandura. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 776-786. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.776

Haralambous, B., Haines, T. P., Hill, K., Moore, K., Nitz, J., & Robinson, A. (2010). A protocol for an individualised, facilitated and sustainable approach to implementing current evidence in preventing falls in residential aged care facilities. BMC Geriatrics, 10(1), 8-8. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-10-8

Henwood, T., Neville, C., Baguley, C., Clifton, K., & Beattie, E. (2015). Physical and functional implications of aquatic exercise for nursing home residents with dementia. Geriatric Nursing, 36(1), 35-39. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.10.009

Heyn, P., Abreu, B. C., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2004). The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: A meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85, 1694-1704. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.019

James, I., Blomberg, K., & Kihlgren, A. (2014). A meaningful daily life in nursing homes - a place of shelter and a space of freedom: A participatory appreciative action reflection study. BMC Nursing, 13(1), 19-19. doi:10.1186/1472-6955-13-19

Khoo, Y. J., van Schaik, P., & McKenna, J. (2014). The happy antics programme: Holistic exercise for people with dementia. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 18, 553-558. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.02.008

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. In J. Katz, S. Peace & S. Spur (Eds.), Adult lives: A life course perspective (89-99) Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9yxM5Q0BGGoC&oi=fnd&pg=PA89&dq=Dementia+reconsidered:+The+person+comes+first&ots=_I-0NHtprv&sig=SMk8Lzzk7_dG5iMHU0haRoKdGXk#v=onepage&q=Dementia%20reconsidered%3A%20The%20person%20comes%20first&f=false

Kukull, W. A., Larson, E. B., McCormick, W., Teri, L., Buchner, D. M., Logsdon, R. G.. . Barlow, W. E. (2003). Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. Jama, 290, 2015-2022. doi:10.1001/jama.290.15.2015

Olsen, C. F., Telenius, E. W., Engedal, K., & Bergland, A. (2015). Increased self-efficacy: The experience of high-intensity exercise of nursing home residents with dementia - a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 379. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1041-7

Smith, K., Flicker, L., Lautenschlager, N. T., Almeida, O. P., Atkinson, D., Dwyer, A., & Logiudice, D. (2008). High prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment in Indigenous Australians. Neurology, 71, 1470-1473. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000320508.11013.4f

Teitelman, J., Raber, C., & Watts, J. (2010). The power of the social environment in motivating persons with dementia to engage in occupation: Qualitative findings. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 28, 321-333. doi:10.3109/02703181.2010.532582

Teri, L., Logsdon, R. G., & McCurry, S. M. (2008). Exercise interventions for dementia and cognitive impairment: The seattle protocols. The Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging, 12, 391-394. doi:10.1007/BF02982672

Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., Baalen, A. v., Sixma, H. J., & Lange, J. d. (2011). How to evaluate quality of care from the perspective of people with dementia: An overview of the literature. Dementia. The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 10(1), 112-137. doi:10.1177/1471301210369320

Williams, A. K. (2005). Motivation and dementia.(lack of motivation, apathy frequent problems in the rehabilitation of persons with dementia). Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 21, 123. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=106505578

Wood, W., Womack, J., & Hooper, B. (2009). Dying of boredom: An exploratory case study of time use, apparent affect, and routine activity situations on two alzheimer's special care units. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 337-350. doi:10.5014/ajot.63.3.337

Yao, L., Giordani, B., & Alexander, N. B. (2008). Developing a positive emotion-motivated tai chi (PEM-TC) exercise program for older adults with dementia. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 22, 241-255. doi: 10.1891/0889-7182.22.4.241