Motivation and emotion/Book/2011/Anger

Understanding and managing anger

Overview

[edit | edit source]

We have all seen and experienced the effects of anger at some point in our lives, We have all been angry at others, ourselves, or had people angry at us. At times, we may have felt driven or empowered by our anger (Berkowitz & Harmon-Jones, 2004); conversely it may have led to consequences that later made us feel regretful, embarrassed or despondent. Anger is a powerful emotion often associated with fury, conflict and aggression and being on the receiving end of it at times can be confronting and frightening. For these reasons, anger is often seen as a “negative emotion”, however this is an over simplification (Izard, 1982), as anger is an essential emotion for dealing with physical and social changes in our environment (Keltner & Gross, 1999), such as potential threats (Reeve, 2009), and can be a useful drive for enforcing social norms and for informing people when their behaviour is not okay (Reeve, 2009; Wright, Day & Howells, 2009).

With that said, anger can also be problematic when it is poorly or not managed (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002; Wright, Day & Howells, 2009) and in such circumstances, it is a contributor to physical health problems such as coronary heart disease (Glazer, Ruiz & Gallo, 2004) and high blood pressure (Everson, 1998), as well as social problems such as aggression (Cornell, Peterson & Richards, 1999), family violence (Wolf and Vangie, 2003), violent crime (Smith & Thomas, 2000)and substance abuse (Eftekhari, Turner & Larimer, 2004).

Focus

[edit | edit source]It will be the focus of this textbook chapter to discuss some psychological theories as to the cause of anger, the effects anger causes on the body, ways in which we can measure and understand anger, and finally, discuss techniques in which anger can be managed based on psychological research.

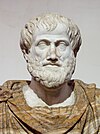

| “ |

Anybody can become angry - that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way - that is not within everybody's power and is not easy.

|

” |

Definitions

[edit | edit source]Aggression: Aggression is a motor behaviour that is expressed as a physical action intended to hurt or harm another person, or to destroy a property (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002).

Anger: An emotion usually triggered in response to situations that are perceived as threatening, harmful, unjust (Keltner & Gross, 1999) or an obstacle (Reeve, 2009), eliciting behaviours that are seen as destructive such as biting or hitting (Reeve,2009).

Cortisol: is an adrenal hormone produced in response to stress (Elseiver, 2005).

Rumination: is denoted by uncontrollable repetitive thoughts in regards to a distressing occurrence (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009).

Self-focused rumination: is when the result of a distressing situation gets an individual to focus inwards, and evaluate their current situation with their personal standards, when a discrepancy arises and the individual is unable to reduce it, it results in negative feelings (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009).

Provocation-focused rumination: occurs when an individual repeats an anger inducing incident in their mind, focusing on the angry feelings from the event with thoughts of revenge (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009).

|}

Why we get angry - Theory meets science[edit | edit source]Like many things, it is difficult to understand something complex by looking at it on a single level, the cause of Anger, its effects on the body and its expression is no different. Many theories on the causes of Emotions such as anger, and the stages in which it occurs exist. These theories can be better understood by dividing them into two types: these are Cognitive explanations, which state that cognition is the first step to experiencing emotion and Biological explanations which dictate that biology occurs before Cognition. It will be the focus of this part of the textbook chapter to explain broadly a few of these different theories and the criticisms associated with them. These explanations will be used to provide you with an understanding of the different ways we can experience Anger so that later in the chapter we can build on these theories to provide useful techniques in its management. Biological explanations[edit | edit source]With the biological explanation for emotions, it is claimed that the physiological effects of an emotion are experienced before cognition. One example of a biological theory for emotion is Facial Feedback Hypothesis. Facial Feedback Hypothesis[edit | edit source]Facial Feedback Hypothesis can be understood in four steps:

Criticisms[edit | edit source]

Role of the Autonomic Nervous System[edit | edit source]Some theorists believe that the Autonomic Nervous System may play a role in triggering emotions in response to environmental events that pose a threat to a person or organism (Levenson, 1988). The Autonomic Nervous System, responsible for the monitoring and functioning of circulation, respiration, digestion, metabolism, secretions, body temperature and reproduction (Lundy-Ekman, p.169, 2007), has been thought to have distinctive patterns of activity associated with certain emotions considered beneficial for survival (Levenson, 1988; Reeve, 2009; Sinha, 1996).  Blue = parasympathetic Red = sympathetic. Recent research suggests this may be the case for certain core emotions such as fear, disgust, sadness and anger (Reeve, 2009), though not all emotions have such distinctive ANS activity. In the case of anger eliciting situations or events, heart rate is recorded to significantly increase (Sinha, 1996) as well as systolic blood pressure (Sinha, 1996). It is hypothesised that this increase in blood pressure boosts isometric muscle strength and the accuracy of sensory intake which in turn helps prepare the body for physical altercation (Schwartz, 1981 cited in: Sinha, 1996). Criticisms:[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Explanations[edit | edit source]Appraisal Theory is used to explain emotions that may occur due to cognitions. Appraisals are a form of judgment made in regards to a situation or event that occurs, this event may be seen as either 'good' or 'bad'. In order for a judgment to be formed the event must have some sort of significance to the individual, such as implications for their well-being (Reeve, 2009). According to Reeve (2009) cognitive emotion theorist agree that:

Example of an Appraisal: A co-worker has accused you of using a mobile phone during work hours. Your boss has already made it clear to all employees that this interferes with your job role and therefore is not allowed. You are shocked to receive an email from your boss warning you that if you continue to use your phone during office hours you will have to find a new job. Upon receiving the email the following happens:

|

Measuring problematic anger[edit | edit source]Unlike anxiety and depression disorders, Anger related problems are under-researched and under-defined (DiGiuseppe & Tafrate, 2003), this makes it difficult to diagnose problematic anger, as it may take on many forms. Nevertheless, the purpose of this part of the textbook chapter will be to give a brief summary of the ways in which anger can be measured, in order to help you become more aware of your anger and to judge yourself, whether or not your anger is problematic. Duration and rumination[edit | edit source]Rumination is characterised by uncontrollable repetitive thoughts towards a distressing event or situation (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009) and is considered a form of coping style which serves to increase the length (or duration) of time in which we experience Anger (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009). Anger rumination can be understood by looking at the focus of Anger. As Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen (2009) see it, two potential such focuses exist, these are Self-focused rumination and 'Provocation-focused rumination'. Self-focused rumination is described to occur when an a distressing situation gets an individual to turn their anger inwards and focus on the self, which in turn is thought to increase self-awareness. It is hypothesised by self-awareness theory, that this causes individuals to initiate a process where they compare their current state with their personal standards (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009). When an inconsistency arises and the individual is unable to reduce it, this results in negative feelings and thoughts (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009). On the other hand, people may also ruminate Angry thoughts towards events or people that have made them angry, this is know as Provocation-focused rumination and is usually accompanied by thoughts of blame towards those that are seen to have made us angry (Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell & Pedersen, 2009).

Findings of Anger Rumination[edit | edit source]In a study by Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell and Pedersen (2009) those who used Self-focused rumination as style of coping where found to have higher cortisol levels (a hormone typically linked to stress (Elseiver, 2005)) at the end of the study than those who where told to perform distracting tasks after being provoked. It was also found that those in the Provactation-focused rumination condition had higher levels than those in the distraction condition, however this seemed to be dependent on the processing style of the individuals. At the end of the provocation stage of the experiment, participants in where told to write an essay where their attention was either directed to the experimenter who had provoked them (Provocation-focused rumination condition)or towards how they felt they had gone in the test (Self-focused rumination condition). Those in the distraction condition where told to visualise and write about their post office. All essays where then appropriately analysed. It was found that those in the Provocation-focused condition did not all have higher cortisol levels than those in the distraction condition. The discrepancy found in the participants of the Provocation-focused condition was attributed to the processing style of the individuals in writing the essay. Analysis on the essays revealed that those who used more distanced descriptions of the experimenter and the process involved where found to have similar cortisol levels to those in the distraction condition, whereas those who were more emotionally reactive in the provocation-focused condition had higher levels of cortisol. Implications of Rumination research[edit | edit source]The experiment by Denson, Fabiansson, Creswell and Pedersen (2009) indicates the following:

Frequency[edit | edit source]In understanding Anger it is also important to understand how frequently Anger occurs. Whilst some people may experience Anger quite frequently, in many different situations and circumstances, others will not (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002). One way to understand the frequency in which Anger occurs is to look for common situations or factors that occur when we get Angry. These common influences are typically called 'Triggers' (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002). Intensity and disproportion[edit | edit source]In order to understand problematic Anger it is important to measure the intensity of Anger. The intensity of Anger can be measured as mild to strong (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002), and depend on several factors. Those who experience strong intense levels of Anger may do so due to distorting cognitions. For example they may personalise feedback to see it in a perspective that serves to invigorate that Anger (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002). For this reason, it is important to become aware of thoughts and cognitions that may increase levels of anger. This will be covered in the textbook chapter under Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.

|

Dealing with anger[edit | edit source]The Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Approach[edit | edit source]The aim of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is to provide people with both Cognitive and Behavioural Strategies to deal with maladaptive thinking and behaviours . This approach has been especially successful with Anger problems (Beck & Fernandez, 1998; DiGiuseppe, Tafrate, 2003), with some researchers arguing that the rates of success are higher than those seen in depression (Beck & Fernandez, 1998). Cognitive behavioural therapy uses a variety of methods to deal with problematic behaviours such as relaxation techniques, cognitive re-structuring, problem-solving and stress inoculation, using principles of learning theory and information processing to achieve its means (Beck & Fernandez, 1998). One particular form of CBT that has been particularly successful with anger is that of Stress Inoculation Training (SIT) (Beck & Fernandez, 1998). This platform originally developed for anxiety uses three phases to deal with problematic behaviours (Meichenbaum, 1975 as cited in: Beck & Fernandez, 1998). These phases are cognitive preparation, skill acquisition and application training (Beck & Fernandez, 1998). It will therefore be the purpose of this part of the textbook chapter to give a brief overview of these phases and draw on the research covered to give it an application to problematic Anger. Cognitive Preparation[edit | edit source]

Skill Acquisition[edit | edit source]According to Beck & Fernandez (1998) in the skill acquisition stage people can be taught relaxation skills which in turn can then be coupled with their self statements.

Application Training[edit | edit source]In this final stage, the new skills acquired from the two initial stages are tested by exposing individuals to their anger triggers through role-play (Beck & Fernandez,1998).

|

Quiz[edit | edit source]This section will offer a quick quiz in order to aid recall and retainment of chapter information on Anger.

|

See also[edit | edit source]These links redirect to sites within the Motivation and Emotion book or within Wikipedia which are relevant to the content on this page.

References[edit | edit source]Beck, R., & Fernandez, E. (1998). Cognitive-behavioural therapy in the treatment of anger: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, (1), 63-74. Berkowitz, L., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2004). Toward an understanding of the determinants of anger. Emotion, 4(2), 107-130. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.107 Cornell, D. G., Peterson, C. S., & Richards, H. (1999). Anger as a predictor of aggression among incarcerated adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 108-115. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.108 Del Vecchio, T., & O'Leary, K. D. (2004). Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), 15-34. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.006 Denson, ThomasFabiansson, EmmaCreswell,J.Pedersen, William. (2009). Experimental effects of rumination styles on salivary cortisol responses. Motivation & Emotion, 33(1), 42-48. doi:10.1007/s11031-008-9114-0 DiGiuseppe, R., & Tafrate, R. C. (2003). Anger treatment for adults: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(1), 70-84. doi:10.1093/clipsy.10.1.70 Eftekhari, A., Turner, A. P., & Larimer, M. E. (2004). Anger expression, coping, and substance use in adolescent offenders. Addictive Behaviors, 29(5), 1001-1008. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.050 Elsevier. (2005). TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved November 09, 2001 from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/cortisol Everson, S. A. (1998). Anger expression and incident hypertension. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60(6), 730. Keltner, D & Gross, J. (1999). Functional Accounts of Emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 5(13), 467-580. Lundy-Ekman, L. (2007). Neuroscience Fundamentals for Rehabilitation. Hillsboro, Oregon: Saunders. Levenson, R. W. (1992). Autonomic nervous systems differences among emotions. Psychological Science (Wiley-Blackwell), 3(1), 23-27. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=8561132&site=ehost-live Martin, L., Stepper, S., & Strack, F. (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: A nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 768-777. Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding motivation and emotion. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. Smith, H.,Sandra P. (2000). Violent and nonviolent girls: Contrasting perceptions of anger experiences, school, and relationships. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 21(5), 547-575. doi:10.1080/01612840050044285 Smith, Timothy W.Glazer, KellyRuiz, John M.Gallo,Linda C. (2004). Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: An interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1217-1270. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x Wolf, K. A. F.,Vangie A. (2003). Family violence, anger expression styles, and adolescent dating violence. Journal of Family Violence, 18(6), 309-316. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pbh&AN=11185532&site=ehost-live External links[edit | edit source]

|