Social Victorians/People/Newcastle

Also Known As

[edit | edit source]

- Family name: Pelham-Clinton

- Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne

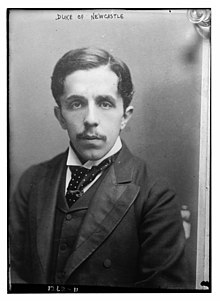

- Henry Pelham Archibald Douglas Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (22 February 1879 – 30 May 1928)[1]

- Henry Pelham Alexander Pelham-Clinton, 6th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (25 January 1834 – 22 February 1879)[2]

- Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (22 May 1811 – 18 October 1864)[3]

- Earl of Lincoln

Acquaintances, Friends and Enemies

[edit | edit source]Organizations

[edit | edit source]Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle

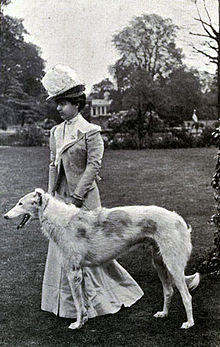

[edit | edit source]Kathleen Pelham-Clinton, Duchess of Newcastle

[edit | edit source]- Organizations for dog breeding: Fox Terriers (smooth and wire), Borzois, Whippets, Scottish Deerhounds, Clumber Spaniels

- Charles Henry Lane dedicated his 1902 Dog Shows and Doggy People to her, wrote about her in the book and included an image of her with one of her championship Borzois (right) as the frontispiece.[5]

Timeline

[edit | edit source]1889 February 20, Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle and Kathleen Florence May Candy married.[6]

1894, Cannadine says, "Lord Edward Pelham Clinton was brother of the sixth Duke of Newcastle, and was Master of the Household from 1894–1901."[7]:245

1897 June 28, Monday, according to the Morning Post, the Duke and Duchess of Newcastle were invited to the 28 June Queen's Garden Party, the official end of the Diamond Jubilee celebrations in London.[8]

1897 July 2, Friday, Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke and Kathleen, Duchess of Newcastle-under-Lyne attended the Duchess of Devonshire's fancy-dress ball at Devonshire House. (Kathleen Pelham-Clinton, Duchess of Newcastle is #150 on the list of people who attended; Henry Pelham-Clinton, Duke of Newcastle is #564.)

Costume at the Duchess of Devonshire's 2 July 1897 Fancy-dress Ball

[edit | edit source]

Kathleen, Duchess of Newcastle

[edit | edit source]At the Duchess of Devonshire's 2 July 1897 fancy-dress ball, Kathleen Pelham-Clinton, Duchess of Newcastle sat at Table 3[9]:p. 7, Col. 5a in the first seating for supper and was Princess Dashkova.

Esmé Collings' portrait of Kathleen Pelham-Clinton in costume (left) is photogravure #2 in the album presented to the Duchess of Devonshire and now in the National Portrait Gallery.[10] The printing on the portrait says, "The Duchess of Newcastle as Princess Dashkoss," with a Long S in Duchess and Princess.[11] (It may not actually say Dashkoss, because the flourish at the end of the word does not look like the other Long S; neither does it look like an f. The spelling Dashkoss is unusual in any event: it should be Princess Dashkova, although an 1905 exhibit of 18th and 19th Russian portraits spelled it Dashkoff,[12] which could have been a mispresentation of the Long S.)

The portrait of Comtesse Dashkova (right) is not a portrait of Princess Dashkova, and it is not the original, if one exists, of the costume worn by the Duchess of Newcastle, although the Duchess's costume has 19th-century elements similar to ones in the dress in this painting.

Maria Louise Ermigna Descemet's 1847–1848 recreation of a 1780s head-and-shoulders portrait by Dmitry Levitsky (1735–1822)[13] imagines the dress, the flowers, the dog, the fan, the seated figure on a chair and the background.[14] Descemet's painting is not of the Princess Dashkova who was Catherine II's confidante, as the woman who sat for this was Comtesse Catherine Alexeyevna Worontzoff (1761–1784), a composer and harpsichordist who lived only into her early 20s.[15] The Comtesse was also briefly at the court of Catherine II, as a maid of honor.[14]

Princess Dashkova would have been in her 40s in the 1780s, when Levitsky painted this portrait.[16] Kathleen, Duchess of Newcastle was about 25 at the time of the ball. We cannot know whether the Duchess of Newcastle saw this portrait and, if she did, if she knew of any doubts about the identity of the sitter. A copy of Descemet's portrait was published in a magazine in 1870 and 1871: "In 1870 and 1871, the magazine 'Russian Antiquity' published the most famous, but riddled with errors, list of ladies-in-waiting of the 18th century, compiled by P. F. Karabanov" [translation by Google Translate].[17]

The Historical Princess Dashkova

[edit | edit source]Princess Dashkova was Yekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova (1743–1810), politically active friend of Catherine II of Russia.[18] With a very long list of intellectual achievements, she repeatedly broke new ground for women in Russia, including founding the Russian Academy and then being its president and being invited by Benjamin Franklin to be the first woman member of the American Philosophical Society.[18] She also asked to be a colonel of the Imperial Guards, which Catherine denied.

It can be difficult even now to identify which of the possible options was the Princess Dashkova the Duchess of Newcastle was thinking of because her name has been anglicized so many ways over time. The Princess Dashkova described here has been identified and has authority files in a number of places (e.g., FAST, ISNI, and VIAF, as well as a number in the authority files of many countries). But who exactly the Duchess of Newcastle was thinking of and which account of her life, if any, is impossible to be certain about.

The 9th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, which would have been available to the Duchess of Newcastle or her costumier, has an article on Katherine R. W. Dashkoff. From the article on Princess Catherina Dashkoff:

DASHKOFF, CATHERINA ROMANOFNA WORONZOFF, PRINCESS (1744–1810), was the third daugliter of Count Roman Woronzoff, a member of the Russian senate, distinguished for his intellectual gifts. She received an exceptionally good education, having displayed from a very early age the masculine ability and masculine tastes which made her whole career so singular. She was well versed in mathematics, which she studied at the university of Moscow, and in general literature her favourite authors were Bayle, Montesquieu, Boileau, Voltaire, and Helvetius. While still a girl she was connected with the Russian court, and became one of the leaders of the party that attached itself to the Grand Duchess (afterwards Empress) Catherme. Before she was sixteen she married Prince Dashkoff, a prominent Russian nobleman, and went to reside with him / at Moscow. In 1762 she was at St Petersburg and took a leading part, according to her own account the leading part, in the coup d'état by which Catherine was raised to the throne. (See Catnerine II., vol v. p. 233). Another course of events would probably have resulted in the elevation of the Princess Dashkoff’s elder sister, Elizabeth, who was the imbecile and unfortunate emperor’s mistress, and in whose favour he made no secret of his intention to depose Catherine; but this fact, by inflaming the princess’s jealousy, rather impelled her to the action she took than deterred her from it. Her relations with the new empress were not of a cordial nature, though she continued devotedly loyal. Her blunt manners, her unconcealed scorn of the male favourites that disgraced the court, and perhaps also her sense of unrequited merit, produced an estrangement between her and the empress, which ended in her asking permission to travel abroad. The cause of the final breach was said to have been the refusal of her request to be appointed colonel of the imperial guards. Her husband having meanwhile died, she set out in 1768 on an extended tour through Europe. She was received with great consideration at foreign courts, and her literary and scientific reputation procured her the entrée to the society of the learned in most of the capitals of Europe. In Paris she secured the warm friendship and admiration of Diderot and Voltaire. She showed in various ways a strong liking for England and the English. She corresponded with Garrick, Dr Blair, and Principal Robertson; and when in Edinburgh, where she was very well received, she arranged to intrust the education of her son to Principal Robertson. In 1782 she returned to the Russian capital, and was at once taken into favour by the empress, who strongly sympathized with her in her literary tastes, and specially in her desire to elevate Russ [sic] to a place among the literary languages of Europe. Immediately after her return the princess was appointed “directeur” of the St Petersburg Academy of Arts and Sciences; and in 1784 she was named the first president of the Russian Academy, which had been founded at her suggestion. In both positions she acquitted herself with marked ability. She projected the Russian dictionary of the Academy, arranged its plan, and executed a part of the work herself. She edited a monthly magazine; and wrote at least two dramatic works, The Marriage of Fabian, and a comedy entitled Toissiokoff. Shortly before Catherine’s death the friends quarrelled over a tragedy which the princess had allowed to find a place in the publications of the Academy, though it contained revolutionary principles, according to the empress. A partial reconciliation was effected, but the princess soon afterwards retired from court. On the accession of the Emperor Paul in 1796 she was deprived of all her offices, and ordered to retire to a miserable village in the government of Novgorod, “to meditate on the events of 1762.” After a time the sentence was partially recalled on the petition of her friends, and she was permitted to pass the closing years of her life on her own estate near Moscow, where she died on the 4th January 1810.

The Memoirs of the Princess Dashkoff written by herself were published in 1840 in London in two volumes. They were edited by Mrs W. Bradford, who, as Miss Wilmot, had resided with the Princess between 1803 and 1808, and had suggested their preparation.[19]

Catherine became regent of Russia with the help of Princess Dashkoff and others:

The ambition of Catherine would probably have been satisfied with the prospect of governing Russia through her husband, but he was too wayward a person to be an obedient instrument; and he soon publicly insulted her beyond forgiveness by compelling her to decorate his mistress, the Countess Woronzoff [Elizabeth, sister of Caterina, Princess Dashkoff], with the order of St Catherine. This and other matters, and the growing alienation of a long and distasteful married life, brought on a crisis. It became clear that they could not live together; and Catherine began to adopt precautionary measures in self-defence. She had little difficulty in doing so most effectively. The Orloffs, influential persons in the Russian guards, were devoted to her; the eldest, Gregory, was her lover. Those men, with the help of the Princess Dashkoff, Count Panin (the tutor of her son Paul), and others, planned the overthrow of Peter. Early on the morning of the 9th July (1762), Catherine was awakened at the palace of Peterhof by Alexis Orloff with the injunction to act immediately; they had been betrayed. Accordingly, she set out for the capital, and finding Gregory Orloff on the spot, appealed to the guards, who were easily induced to raise the standard of revolt. In the church, the priests anointed her regent in the name of her son, while, outside, the Orloffs had her proclaimed empress in her own right.[20]

Newspaper Reports

[edit | edit source]No newspaper description of the Duchess of Newcastle's costume exists at this time.

- Kathleen, Duchess of Newcastle was one of the Ladies and Gentlemen of the Court of Catherine II of Russia.[21]:p. 12, Col. 1b [9]:p. 7, Col. 5b

- In the suite of Catherine II of Russia: "Lady Raincliffe took the part of Catherine II. of Russia in a dress of white satin. ... In her suite were Lady Margaret Spicer as Countess Soltykoff, the Duchess of Marlborough in a superbly-handsome dress of the same period; the Duchess of Newcastle; Lady Henry Bentinck; the Countess of Yarborough; Lady Mildred Denison; and the Hon. Mrs. Erskine and her daughter."[22]

Commentary on the Duchess of Newcastle's Costume

[edit | edit source]Because Lafayette did not take the Duchess's photograph (Esmé Collings did), high-resolution copies we can look at more closely and different views do not exist. We have a lot of uncertainty about elements of this costume.

The 18th-century coat of arms of the Russian Empire (right), which is prominent on the costume of Viscountess Raincliffe as Catherine II of Russia, appears on the Duchess of Newcastle's costume as well, on the cloak.

The Duchess's costume looks very French, suggesting the widespread French influence among the aristocracy in Russia at this time. If the Duchess did not see any images of Russian aristocrats, then perhaps she or her costumier looked at images of French women from the mid to late 18th century. Also, perhaps they saw the portrait of Comtesse Catherine Vorontsova (above, right).

- The Duchess of Newcastle appears to be wearing a wig (a clear line at the hairline plus little curls to cover the front edge of the wig). Other photographs of the Duchess show her hair to be dark and straight. The curly, wavy wig is light, but it does not look powdered.

- The Prince of Wales's plumes in her hair are attached to the back of her head, perhaps; some kind of ornament is on the wig as well. We can see ringlets, which might have been only on the sides but could also have gone around the back of the neck, covering the bottom of the wig.

- The jewelry at the Duchess's neck is a choker of at least 3 strands of pearls or jewels with another strand or necklace below it. This jewelry looks very rich and is probably the Duchess's own.

- The elements of this unusual bodice are the straps, the bow, the under-bodice, and the revers.

- Her bodice is unusual in that it has narrow straps that might be open work or jeweled braid, in that her shoulders are bare and in that it is asymetrical at the top of the revers. If they are open work, the straps may match the bow at the top center of the bodice.

- The bow at her bust may be a piece of jewelry rather than braid. French style at the time the costume is purportedly set included rows of bows of graduated size down the front of the bodice. The Duchess of Newcastle's single bow is reminiscent of this French style because of its location and size.

- A fitted under-bodice that is encrusted with jewels shows beneath the folded edge of the more loosely fitted outer-bodice, which actually may be revers that form a stitched V below the waist. The structure of the late-Victorian corset supports the V and holds it in place.

- The bottom of the bodice (in this case, a double-V) meets the upside-down V made by edges of the overskirt, a design far more popular in the Victorian age than the 18th century.

- What looks like revers may be an over-bodice that goes around her sides to the back of the dress.

- The revers may be jacquard woven or translucent over the heavily decorated under-bodice.

- A long loop of pearls is attached to one of the ornaments at the top of the revers, likely the one at the strap. Oddly, the pearls disappear on her right side, suggesting that the photograph was retouched to make her waist look smaller, which might also explain the rough outside edge of the right rever and the uneven line of the skirt where the pearls intersect it.

- The sleeves are not set into the straps but are set into the bodice under her arms. These complex sleeves are made of multiple puffs as well as ruffles from the elbow up to the top, near the shoulder. It is possible that elastic separates the puffs and ruffles and keeps the top of the sleeve in place.

- She is holding a large closed folding fan in her right hand. Is she holding something in her left hand?

- The satin overskirt has a band of embroidery only on the front edges, not at the bottom or decorating the rest of the skirt.

- The band of embroidery has some kind of trim, perhaps ribbon loops or pleats, on the skirt side.

- Like the bodice and the edges of the overskirt, pearls and jewels on the underskirt make the embroidery more three-dimensional. The ornate embroidery on the underskirt just comes up to the knees.

- What is probably a voluminous cloak is draped on the chair behind and beside the Duchess. Made of satin, but probably not the same color as the dress, the cloak features the double-headed black eagle coat of arms of the Russian Empire, in a version from the 18th-century.

Questions about the Duchess of Newcastle's Costume

[edit | edit source]- Were all the women in the court of Catherine II costumed in white satin?

- Did they all use the double-headed black eagle as well?

- Is any of the jewelry here extant now? Are there images showing it from the 19th or early 20th century?

Henry, Duke of Newcastle

[edit | edit source]Henry Pelham-Clinton, Duke of Newcastle was also present at the ball.[21]:p. 12, Col. 4b We know nothing about his costume.

Demographics

[edit | edit source]Residences

[edit | edit source]Family

[edit | edit source]- Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (22 May 1811 – 18 October 1864)[3]

- Lady Susan Harriet Catherine Hamilton (9 June 1814 – 28 November 1889)[23]

- Henry Pelham Alexander Pelham-Clinton, 6th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (25 January 1834 – 22 February 1879)

- Lord Sir Edward William Pelham-Clinton (11 August 1836 – 9 July 1907)

- Lady Susan Charlotte Catherine Pelham-Clinton (7 April 1839 – 6 September 1875)

- Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton (23 June 1840 – 18 June 1870)

- Lord Albert Sidney Pelham-Clinton (22 December 1845 – 1 March 1884)

- Lord Sir Edward William Pelham-Clinton (11 August 1836 – 9 July 1907)[24]

- Matilda Jane Cradock-Hartopp ( – 23 October 1892)[25]

- Henrietta Adela Hope (1843[26]–)

- Henry Pelham Alexander Pelham-Clinton, 6th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (25 January 1834 – 22 February 1879)

- Thomas Theobald Hohler ()[26]

- Lady Beatrice Adeline Pelham-Clinton (1862–1935)[2]

- Lady Emily Augusta Mary Pelham-Clinton (1863–1919)[2]

- Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (1864–1928)[1]

- Francis Pelham-Clinton-Hope, 8th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (1866–1941)[2]

- Lady Florence Josephine Pelham-Clinton (1868–1935)[2]

- Henry Pelham Archibald Douglas Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne (28 September 1864 – 30 May 1928)[1]

- Kathleen Florence May Candy (1872 – 1 June 1955)[5]

Relations

[edit | edit source]- Susan Pelham-Clinton?

Questions and Notes

[edit | edit source]- Which one was Susan Pelham-Clinton? (on the list of the mistresses of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales)

- Henrietta Hope was born in 1843, and her parents Henry Thomas Hope and Anne Adele Bichat married in 1851.[26]

- The Hope Diamond was part of the estate inherited by Henry Thomas Hope, Henrietta Hope's father.[26]

- How was the Duke of Newcastle dressed?

Footnotes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Henry Pelham Archibald Douglas Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne." "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-11. https://www.thepeerage.com/p6173.htm#i61730.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Henry Pelham-Clinton, 6th Duke of Newcastle". Wikipedia. 2022-09-27. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Henry_Pelham-Clinton,_6th_Duke_of_Newcastle&oldid=1112660881. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Pelham-Clinton,_6th_Duke_of_Newcastle.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Henry Pelham Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne." "Person Page: 109903." The Peerage: A Genealogical Survey of the Peerage of Britain as well as the Royal Families of Europe https://www.thepeerage.com/p10991.htm#i109903 (accessed November 2022).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle". Wikipedia. 2019-07-13. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Henry_Pelham-Clinton,_7th_Duke_of_Newcastle&oldid=906091587.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Kathleen Pelham-Clinton, Duchess of Newcastle". Wikipedia. 2020-08-11. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kathleen_Pelham-Clinton,_Duchess_of_Newcastle&oldid=972269334.

- ↑ "Kathleen Florence May Candy." "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 2020-11-11. https://www.thepeerage.com/p6174.htm#i61731.

- ↑ Cannadine, David. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. New York: Yale University Press, 1990.

- ↑ “The Queen’s Garden Party.” Morning Post 29 June 1897, Tuesday: 4 [of 12], Cols. 1a–7c [of 7] and 5, Col. 1a–c. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000174/18970629/032/0004 and https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000174/18970629/032/0005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Fancy Dress Ball at Devonshire House." Morning Post Saturday 3 July 1897: 7 [of 12], Col. 4a–8 Col. 2b. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000174/18970703/054/0007.

- ↑ "Devonshire House Fancy Dress Ball (1897): photogravures by Walker & Boutall after various photographers." 1899. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait-list.php?set=515.

- ↑ "The Duchess of Newcastle as Princess Dashkoss." Devonshire House Fancy Dress Ball Album. National Portrait Gallery https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw126430/Kathleen-Florence-May-ne-Candy-Duchess-of-Newcastle-as-Princess-Dashkova.

- ↑ "Княгиня Екатерина Романовна Дашкова (1743-1810) [La Princesse Catherine Romanowna Dachkoff (1743-1810)]." Russian portraits of the 18th and 19th centuries: Edition of Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich of Russia. 1905-1909. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RusPortraits_v2-203_La_Princesse_Catherine_Romanowna_Dachkoff.jpg.

- ↑ "Dmitry Levitzky". Wikipedia. 2023-10-10. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Dmitry_Levitzky&oldid=1179461785. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitry_Levitzky.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The Portrait of Catherine Vorontsova - Louise Descemet . Подробное описание экспоната, аудиогид, интересные факты. Официальный сайт Artefact". ar.culture.ru. Retrieved 2023-11-27. Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. https://ar.culture.ru/en/subject/portret-ekateriny-alekseevny-voroncovoy.

- ↑ "Yekaterina Sinyavina". Wikipedia. 2023-10-29. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Yekaterina_Sinyavina&oldid=1182498457. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yekaterina_Sinyavina.

- ↑ Дессеме, Луиза (1848), Графиня Е.А.Воронцова, видоизмененная копия с оригинала Левицкого, retrieved 2022-01-19. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catherine_Vorontsova_(Senyavina)2.jpg.

- ↑ "Список фрейлин российского императорского двора". Википедия. 2023-10-13. https://ru.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%D0%A1%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%BA_%D1%84%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B9%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%BD_%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_%D0%B4%D0%B2%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0&oldid=133583883. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A1%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%BA_%D1%84%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B9%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%BD_%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_%D0%B4%D0%B2%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Yekaterina Vorontsova-Dashkova". Wikipedia. 2022-01-17. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Yekaterina_Vorontsova-Dashkova&oldid=1066311115. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yekaterina_Vorontsova-Dashkova.

- ↑ "DASHKOFF, CATHERINA ROMANOFNA WORONZOFF, PRINCESS." The Encyclopaedia Britannica https://archive.org/details/encyclopaedia-britannica-9ed-1875/Vol%206%20%28CLI-DAY%29%20193819109.23/page/830/mode/2up.

- ↑ "CATHERINE II." Vol. V: 233, Col. 2c. https://archive.org/details/encyclopaedia-britannica-9ed-1875/Vol%205%20%28Canon-Cleves%29%20193323019.23/page/232/mode/2up.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Ball at Devonshire House." The Times Saturday 3 July 1897: 12, Cols. 1a–4c The Times Digital Archive. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ "Duchess of Devonshire's Fancy-Dress Ball. Brilliant Spectacle." The Guernsey Star 6 July 1897, Tuesday: 1 [of 4], Col. 1–2. British Newspaper Archive https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000184/18970706/003/0001.

- ↑ "Lady Susan Harriet Catherine Hamilton." "Person Page 109902." The Peerage: A Genealogical Survey of the Peerage of Britain as well as the Royal Families of Europe https://www.thepeerage.com/p10991.htm#i109902 (accessed November 2022).

- ↑ "Lord Sir Edward William Pelham-Clinton." "Person Page 61800." The Peerage: A Genealogical Survey of the Peerage of Britain as well as the Royal Families of Europe https://www.thepeerage.com/p6180.htm#i61800 (accessed November 2022).

- ↑ "Matilda Jane Cradock-Hartopp." "Person Page 61801." The Peerage: A Genealogical Survey of the Peerage of Britain as well as the Royal Families of Europe https://www.thepeerage.com/p6181.htm#i61801 (accessed November 2022).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "Henry Thomas Hope". Wikipedia. 2023-06-12. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Henry_Thomas_Hope&oldid=1159770565. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Thomas_Hope.