Motivation and emotion/Book/2024/Inner talk in achieving high performance

How does inner dialogue influence motivation for high achievement?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

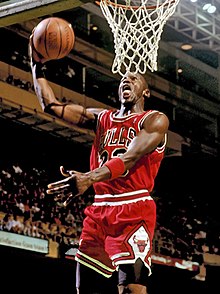

Few moments in sports history are as iconic as Michael Jordan "Flu Game" during the 1997 NBA Finals, where, despite severe illness, he used Intrapersonal communication to score 38 points, leading the Chicago Bulls to victory. As Jordan battled fever, fatigue, and dehydration, his inner dialogue became the driving force that transformed a moment of vulnerability into one of triumph. This extraordinary event prompts us to ask: What role does inner talk play in the pursuit of high achievement? How can the conversations we have with ourselves propel us to overcome challenges and reach new levels of performance? This chapter explores the intricate relationship between inner dialogue and motivation, examining how the thoughts we entertain and the words we silently speak to ourselves can shape our abilities, drive our actions, and ultimately determine our success in high-pressure situations. Just as Jordan's relentless self-talk fuelled his historic game, mastering inner dialogue can unlock the potential for peak performance in any aspect of life. |

According to Van Raalte et al. (2016), intrapersonal communication (self-talk/inner talk) refers to an individual's internal dialogue used to guide themselves through events. It influences self-regulation, motivation, and focus, and can be applied in various contexts, including high-pressure environments such as sports, academics, and professional settings. The challenge lies in the effects of positive and negative self-talk on motivation and performance. Positive self-talk enhances performance, while negative self-talk can be detrimental (Latinjak et al., 2019; Tod et al., 2017). Understanding how different forms of self-talk affect motivation and performance is crucial for optimising cognitive strategies for high achievement.

Different types of self-talk directly impact performance. For example, motivational self-talk, which involves encouraging self-statements, increases persistence and effort by boosting confidence. It is particularly effective in motivating individuals to overcome challenges, especially in high-pressure settings, by increasing self-efficacy (Theodorakis et al., 2000; Van Raalte et al., 2016). Positive self-talk also increases long-term motivation by regulating emotions and anxiety, building resilience (Hatzigeorgidis et al., 2011). In contrast, negative self-talk, such as "I am going to fail," leads to increased anxiety and decreased task engagement by fostering self-doubt and reducing motivation (Latinjak et al., 2019). Replacing negative self-talk with positive dialogue is essential for maintaining motivation and achieving high performance (Van Raalte et al., 2016).

Psychological research emphasises self-talk as a tool for maintaining motivational focus, moderated by self-efficacy and self-regulation. Self-regulation, the ability to manage thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, allows individuals to remain focused on goals even in high-pressure contexts (Van Raalte et al., 2016). Self-efficacy, or one’s belief in their ability to succeed, is key to motivation. Increasing self-efficacy and using positive self-talk boosts persistence and effort towards a goal. Those who engage in affirming self-talk are more likely to achieve high-performance outcomes through sustained motivation under challenging circumstances (Hatzgeorgiadis et al., 2011; Latinjak et al., 2019). Cognitive behavioural strategies and mindfulness techniques help individuals shift their self-talk from negative to positive, enhancing motivation and emotional regulation. By identifying their self-talk type, individuals can adjust it to promote higher performance (Beckmann & Kellmann, 2017; Rashid & Seligman, 2018).

This chapter explores key questions to understand the role of self-talk in motivation and performance in high-pressure environments. It examines types of self-talk, underlying psychological mechanisms, and strategies for fostering positive inner dialogue.

Quiz

Intrapersonal communication, or self-talk, is primarily used to:

a) Communicate with others

b) Guide oneself through events and regulate motivation and focus

c) Create a distraction during stressful tasks

d) Ignore emotions and decisions

Positive self-talk generally enhances performance, while negative self-talk can harm motivation and performance.

- True

- False

Disclaimer: The answers to these questions are provided at the end of the page.

|

The Theories

[edit | edit source]Self-talk is crucial in motivating individuals to achieve high performance across many contexts, from professional environments to sports. Several seminal theories, including goal-setting theory, dual-process theory, self-regulation theory, and self-efficacy theory, provide a framework in which inner dialogue plays a crucial role in motivating high performance.

Goal-setting theory

[edit | edit source]Locke & Latham (2002) highlight self-talk as a motivational tool that helps individuals stay committed to clear, specific and challenging goals that result in higher performance. Further, they state that self-talk is a motivational tool that helps individuals persist in their goals when obstacles, fatigue or adversity arise. Latham and Locke (2019) highlight that a professional working on a long-term project uses goal setting to break down goals into manageable steps; further, the professional uses positive self-talk to complete the smaller goals and reinforce their completion to maintain motivation under pressure.

One form of self-talk highlighted by Locke and Latham (2019) is goal-directed self-talk. This self-talk reminds individuals of their commitment to a goal, achievement and performance. Top corporate executives like Ken Chenault, the CEO of American Express, use goal-directed self-talk to remain focused during long-term strategies. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, Chenault employed positive and motivational self-talk to maintain his self-efficacy and lead the company through turmoil. Chenault stated that "the role of a leader is to define reality and give hope" (General Catalyst, 2020); further, Chenault used self-talk to reinforce his ability to stay focussed on long-term strategies, manage his emotions and maintain confidence in himself under a high-pressure situation, to which he ultimately persevered.

Dual-process Theory

[edit | edit source]Kahneman’s (2011) dual-process theory explains that humans think in two ways: system one (automatic, fast, prone to errors) and system two (deliberate, accurate). Self-talk helps transition from instinctual, emotional responses (system one) to goal-oriented thinking (system two), particularly in high-pressure environments. For example, Tom Brady’s self-talk during the 2017 Super Bowl comeback helped him stay focused and execute plays with precision, leading to victory (Boston Magazine, 2017)

Croskerry (2009) states that Emergency Room (ER) workers must often balance intuitive and automatic thinking with reflective and deliberate thinking. System One thinking allows staff to quickly assess routine cases, while System 2 becomes crucial in complex situations to make safe decisions and avoid errors. Physicians can use self-talk to engage different ways of thinking and respond to each stimulus accordingly. For example, physicians may utilise dialogue to slow their thinking and question any assumptions before reacting to a case presented in the ER. The transition between an instinctual response, facilitated by self-talk, is essential to delivering optimal patient outcomes (Croskerry, 2009).

Self-regulation Theory

[edit | edit source]Zimmerman (2000) suggests that self-talk allows individuals to control their behaviour, emotions, and thoughts to pursue personal goals. Self-talk allows individuals to stay focused, manage stress, and overcome adversity that could hinder their performance. It is an efficacious tool of self-regulation, allowing individuals to sustain motivation by reinforcing goal-directed behaviour and emotional control (De La Fuente et al., 2020).

Self-regulating self-talk can be divided into two categories: instructional self-talk, which helps individuals maintain focus on technical aspects of a task, pay attention to detail, and improve execution; and motivational self-talk, which encourages persistence and maintained effort reinforced by self-efficacy and determination (Zimmerman, 2000).

For example, surgeons performing complex operations under immense amounts of pressure often use instructional self-talk to remind themselves to stay on task or follow a system effectively while maintaining emotional control and concentration (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2012). Similarly, air traffic controllers managing crises must exercise great emotional regulation to focus on critical procedures. Further, they can manage their emotions through instructional self-talk, helping them maintain decision-making capabilities under pressure. In contrast, athletes can use motivational self-talk to push through fatigue and maintain effort during high-pressure events or physically demanding efforts (Hatzigeordiafis et al., 2011).

Self-Efficacy Theory

[edit | edit source]Bandura (1977) explains that self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to succeed in a task. High self-efficacy individuals persevere through challenges. Positive self-talk, linked to high self-efficacy, counters negative thoughts and reinforces confidence, boosting motivation and performance (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020).

Simone Biles is one of the greatest gymnasts of all time and often speaks of how she uses self-talk to manage her mental state during competition. She reinforces her belief in her abilities ahead of major events by using affirmations like "you've done this before, you can do this again." The positive inner dialogue enhances her self-efficacy, helping her perform under high-pressure situations, like the Tokyo Olympics (Daza, 2021).

Quiz

Multiple Choice: Which theory highlights using self-talk to stay committed to clear, specific, and challenging goals?

a) Dual-Process Theory

b) Goal-Setting Theory

c) Self-Regulation Theory

d) Self-Efficacy Theory

Drop-Down: According to Kahneman's Dual-Process Theory, which type of thinking is deliberate and more accurate?

- System 1

- System 2

The answers to these questions are provided at the end of the page.

Self-Talk Research

[edit | edit source]Self-talk is a mental strategy that helps individuals regulate their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, enabling them to stay motivated and perform well under pressure (Van Raalte et al., 2016). Studies indicate that the impact of self-talk on motivation varies, depending on both the type of self-talk and how it is applied (Latinjak et al., 2019). Maintaining motivation in high-pressure situations is key to excelling in different areas, though much of the research has primarily focused on sports performance. This highlights the need for further studies in non-sporting contexts, such as education and professional settings (Beckmann & Kellmann, 2017).

Table 1. The main types of self talk identified in the research

| Type of Self-Talk | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Self-Talk | Encouraging and affirming statements that focus on strengths and potential. | "I can handle this challenge," "I’ve prepared well," "I am capable." |

| Negative Self-Talk | Critical, self-defeating, or pessimistic thoughts that focus on weaknesses or failures. | "I’m not good enough," "I always mess things up," "This is too hard for me." |

| Instructional Self-Talk | Self-directed speech that provides specific instructions or cues to guide behavior. | "Keep your eye on the ball," "Breathe deeply and stay calm," "Focus on your form." |

| Motivational Self-Talk | Statements aimed at increasing energy, effort, and persistence toward a goal. | "Keep pushing, you’re almost there," "You’ve got this," "Stay strong and finish." |

| Neutral Self-Talk | Objective, fact-based internal dialogue that lacks emotional content. | "The meeting is at 3 PM," "I missed that shot," "I need to submit the report by Friday." |

| Self-Reflective Self-Talk | Thoughtful, introspective dialogue that involves evaluating past experiences or contemplating future actions. | "What can I learn from this experience?" "How can I improve next time?" "What are my goals for the future?" |

Types of Self Talk

[edit | edit source]Refer to the figures in the Figures section for a table of self-talk types.

Positive self-talk

[edit | edit source]Through reinforcing self-efficacy and helping to regulate emotion, positive self-talk has consistently been shown to enhance performance and motivation (Beckmann & Kellman, 2017; Hatzigeorgiadis et al., 2011). For example, Beckmann and Kellman (2017) conducted an experiment that divided 62 athletes into a self-talk intervention that received training on self-talk strategies and a control group that did not. The athletes were given a "high-pressure task", usually endurance-based and in their specific sport. Moreover, the results indicated that the self-talk group showed a 15% performance under pressure; for example, timed athletes saw faster completion times.

Negative self-talk

[edit | edit source]In contrast, negative self-talk has been shown to have detrimental effects on motivation and performance. In a sporting-based study using 80 competitive athletes, Latinjak et al. (2019) explored the relationship between negative self-talk and athletic performance. Researchers established athletes' base level of self-talk (negative or positive) and, during the study, found that athletes who reported higher levels of negative self-talk exhibited up to a 20% decrease in performance compared to those with neutral or positive self-talk. Latinjak et al. (2019) reported that negative self-talk interrupts cognitive processing and undermines an individual's ability to engage in strategic thinking processes, leading to decreased performance.

Motivational Self Talk

[edit | edit source]Theodroakis et al. (2000) state that motivational self-talk consists of statements that increase effort and persistence, particularly during challenging tasks. Examples of motivational self-talk are phrases such as "I can do this". A study of 72 physical education students assessing the effect of motivational self-talk on their endurance-based motor skills found that the self-talk group performed 13% better than the control group, showing that this type of talk can increase performance and resilience to perseverance and performance through challenges.

Instructional Self Talk

[edit | edit source]Instructional self-talk involves task-specific instructions that help individuals maintain focus and engagement on the technical aspects of their task. Zimmerman & Schunk (2012) found that students who use instructional self-talk during complex problem-solving tasks improve their accuracy by up to 17% compared to those who don't engage in self-talk. Instructional self-talk involves guiding phrases like "First, I need to multiply" that reaffirm focus and engagement with the task while also helping the individual through it.

Neutral Selk Talk

[edit | edit source]According to Van Raalte et al. (2016), Neutral self-talk refers to the fact-based and objective internal dialogue that neither negatively nor positively impacts emotions. Further, they state that neutral self-talk, involving neutral statements like "today was not my day" or "next step is to reattempt", enables individuals to approach decision-making with a balanced and more objective approach, potentially decreasing the influence emotion can have on decision making.

Self Reflective Self-talk

[edit | edit source]In his seminal literature, Bandura (2019) states that self-reflective self-talk involves evaluating one's emotions, decisions and behaviour (Bandura, 2019). Further, he positions that individuals who can reflect on and learn from their experiences can become more self-aware and more capable of making informed decisions under pressure. This kind of self-talk encourages individuals to learn from their reflections on themselves and their experiences to critically assess their actions and refine strategies, which is essential for performing under pressure (Morin, 2011). By continuously engaging in reflective dialogue, individuals can adjust their behaviour and stay motivated through challenging events or periods (Bandura, 2019; Morin, 2011).

Evaluation of Self-Talk Research

[edit | edit source]Numerous studies highlight the benefits of different types of self-talk in sports. However, there needs to be more in understanding how it applies to other high-pressure contexts, like academia and professional environments. For example, Beckmann and Kellmann (2017) found that positive self-talk enhances resilience in athletes. However, these results do not necessarily translate into different performative contexts as people naturally utilise different types of self-talk for different tasks or events. The most critical aspect of the current research is its focus on physical performance under pressure and not cognitive.

Implications of Self-Talk Research

[edit | edit source]In its different forms, self-talk is multifaceted in enhancing motivation and performance across many contexts, if used appropriately. Positive and instructional self-talk has been shown to boost performance by reinforcing self-efficacy and also increasing focus as well as engagement while providing task-specific guidance (Beckmann & Kellmann, 2017; Hatzigeorgiadis et al., 2011; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2012), while negative self-talk can undermine motivation and cognitive processes required to perform under high pressure (Latinjak el al., 2019). Further, neutral and self-reflective self-talk offer unique benefits, particularly in environments where strategic reflection and emotional regulation are required to maintain motivation and performance (Morin, 2011; Van Raalte et al., 2016). The research highlights the positive utility of further research and using self-talk to increase motivation and achieve high performance. However, the lack of contextual diversity in the research makes it challenging to understand which types of self-talk should be utilised in which situations.

Quiz

Multiple Choice: According to research, negative self-talk tends to:

a) Increase performance under pressure

b) Diminish self-efficacy and hinder task engagement

c) Have no impact on performance

d) Improve cognitive flexibility

Yes/No: Is most research on self-talk currently focused on sports performance rather than other high-pressure contexts like professional or academic settings?

- Yes

- No

The answers to these questions are provided at the end of the page.

Integration of Theory and Research

[edit | edit source]

Developing and Enhancing Positive Self-Talk

[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Restructuring

[edit | edit source]Cognitive restructuring is a tool used in self-regulation theory in which individuals are asked to identify negative or unhelpful self-talk and beliefs and consciously replace them with affirming thoughts and statements (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2012). Beckmann & Kellmann (2017) demonstrated the influence of self-talk in their athlete study. Participants who received cognitive restructuring training showed increased resilience and motivation during high-pressure endurance tasks. In day-to-day life, this might mean replacing negative thought patterns about a high stakes presentation with more positive ones, as well as questi0oning the validity of the thought; for example, "I am going to fail" might be replaced with "I have faced challenges before, and I can handle this too", after inquiring about the evidence for the thought. The utility of cognitive restructuring is well demonstrated and documented in high-performance contexts for managing stress, maintaining focus and increasing self-efficacy (Turner et al., 2016). However, more research should be done to assess its influence in another context, such as professional environments, where cognitive demands and emotional stressors differ from those in an athletic setting.

Self-Coaching

[edit | edit source]Self-Coaching is rooted in self-efficacy theory and involves setting specific, achievable goals and using positive self-talk to reinforce one's belief in their ability to achieve them (Bandura, 1997). By setting goals and using affirming statements pertaining to the goals, self-coaching is highly effective in performance contexts; for example, Birrer and Morgan (2010) found that athletes instructed to set specific and actional goals prior to performance saw improved competitive performance. For individuals looking to apply this to other performative contexts, like a deadline in a professional environment, it may involve setting small and manageable goals while using affirming statements to reward the completion of these smaller goals. By doing this, one can progress, maintain motivation throughout a task, and increase self-efficacy throughout the task. The self-efficacy theory supports the effectiveness of self-coaching; however, it suggests that regular reinforcement must be used to maintain motivation, especially when immediate success is not as acquirable (Birrer & Morgan, 2010).

Mastery Experiences

[edit | edit source]A vital aspect of the self-efficacy theory is Mastery Experiences, in which individuals can build confidence by completing tasks (Bandura, 1986). Luthans et al. (2016) found that those in organisational and athletic settings that reflect on past successes enhanced self-efficacy and motivation. Further, individuals improved their confidence and resilience when facing future challenges. For example, after the successful completion of a project or event, individuals should affirm themselves of their success and reflect on their performance while highlighting any strengths in their performance. Research on this theory shows that it has promising utility. However, it stresses an overreliance on success and lacks an emphasis on resilience, which could make it harder to cope with failure (Bandura, 1986; Luthans et al., 2016).

Visualisation and Mental Rehearsal

[edit | edit source]Dual process theory and self-efficacy theory both emphasise visualisation and mental rehearsal as cognitive tools that are beneficial for helping individuals with performance and motivation when paired with positive self-talk (Bandura, 1997; Kahneman, 2011). Visualisation is the cognitive process in which individuals mentally rehearse a task prior to doing it, while mental rehearsal includes not only visualising the task but going through both the cognitive and motor patterns associated with the event (Feltz & Landers, 1983; Guillet & Collet, 2010). Theodorakis et al. (2000) found athletes who practised visualisation before an event experienced a greater sense of control and readiness, leading to better performance. In an applied sense, if an individual has a challenging work presentation, they could envision themselves speaking confidently, engaging with the audience and receiving positive feedback.

Maintaining Positive Self-Talk

[edit | edit source]Positive self-talk supports self-regulation and improves performance (Burnette et al., 2013). Self-reflective self-talk, grounded in self-efficacy and self-regulation theories, helps individuals adjust their thinking patterns. Journaling promotes self-awareness by allowing individuals to replace negative thoughts with more empowering ones (Morin, 2011).

Overcoming Low Motivation, Stress and Challenges

[edit | edit source]Maintaining self-talk is vital; however, overcoming low motivation, stress or facing challenges relating to high performance requires additional strategies. In the social cognitive theory, Bandura (1986) highlights the role of external factors, like social feedback and support, in enabling self-belief. In support of this, Hatzigeorgiadis et al. (2011) showed that athletes who utilised motivational self-talk in conjunction with constructive feedback improved their performance and motivation. This emphasises the value of productive feedback and social elements in motivation and performance to bolster positive self-talk.

For managing stress, Khaneman (2011) explains that instructional self-talk helps individuals shift from emotionally driven thoughts (system one) to deliberate thoughts (system two). Moreover, Zimmerman and Schunk (2012) found that by breaking larger tasks into smaller goals (steps) and using instructional self-talk to guide individuals through the tasks, the participants experienced increased resilience and focus under pressure.

Quiz

Multiple Choice: Which strategy involves identifying negative thoughts and consciously replacing them with positive, affirming statements?

a) Self-coaching

b) Cognitive restructuring

c) Goal-directed self-talk

d) Visualisation

Which of the following strategies is an example of cognitive restructuring as used in self-regulation theory?

a) Reflecting on past successes to build confidence.

b) Mentally rehearsing a task before performing it.

c) Replacing the thought "I am going to fail" with "I have faced challenges before and can handle this too."

d) Setting small, manageable goals and using affirming statements after completing each goal.

Disclaimer: The answers to these questions are provided at the end of the page.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Self-talk (or intrapersonal communication) profoundly impacts self-regulation, motivation, and performance, and it also plays a crucial role in guiding individuals through demanding events (Van Raalte et al., 2016). Research has consistently shown that negative self-talk diminishes focus and motivation, while positive self-talk can increase self-efficacy and emotional regulation (Latinjak et al., 2019; Tod et al., 2017). Different types of self-talk provide contextual benefits, particularly in high-pressure settings; for example, instructional self-talk helps individuals systematically work through a process, while motivational self-talk helps individuals increase their resilience during a performance (Theodorakis et al., 2000; Hatzigeorgiadis., 2011).

Self-talk is supported by many theories, like goal-setting theory, self-regulation theory, self-efficacy theory and dual process theory, as deliberate intrapersonal communication can improve performance. andmtovation by incresing confidence and focus (bandura, 2017; Kahneman, 2011; Locke & Latham, 2002; Zimmerman, 2000). However, a large part of the research has focussed on high performance in athletes, so further research is required to extend self-talk practices to other high-pressure contexts (Beckmann & Kellmann, 2017).

Understanding, improving and maintaining positive self-talk through well-documented strategies like cognitive restructuring and self-coaching can help individuals overcome challenges, stay motivated and achieve high performance in various settings (Beckmann & Kellmann, 2017; Turner et al., 2016).

Quiz

What is a crucial takeaway regarding the role of self-talk in high-pressure environments?

a) It only works in athletic contexts

b) Positive self-talk helps regulate emotions and enhances performance

c) Negative self-talk has no effect

d) Self-talk is only helpful for short-term tasks

Theories such as Goal-Setting Theory, Self-Regulation Theory, and Self-Efficacy Theory all support the positive impact of self-talk on motivation and performance.

- True

- False

The answers to these questions are provided at the end of the page.

Quiz Answers

[edit | edit source]Overview:

- b)

- True

Theories:

- b)

- System 2

Self-Talk Research:

- b)

- Yes

Integration of Theory and Research:

- b)

- (5)

Conclusions:

- b)

- True

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Psycnet.apa.org. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000

Bandura, A. (2019). Applying theory for human betterment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(1), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618815165

Birrer, D., & Morgan, G. (2010). Psychological skills training as a way to enhance an athlete’s performance in high-intensity sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20(s2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01188.x

Burnette, J. L., O’Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029531

ChatGPT. (2024, October 21). Table content [Table generated by ChatGPT]. OpenAI.

Clauss, K. S. (2017, February 13). In a secret Montana cabin, Tom Brady says he feels no pain. Boston Magazine. https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2017/02/13/tom-brady-super-bowl-comeback/

Croskerry, P. (2009). A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Academic Medicine, 84(8), 1022–1028.

Daza, P. (2021). Simone Biles: World class gymnast and mental health advocate. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mind-matters-menninger/202107/simone-biles-world-class-gymnast-and-mental-health-advocate

de la Fuente, J., Amate, J., González-Torres, M. C., Artuch, R., García-Torrecillas, J. M., & Fadda, S. (2020). Effects of levels of self-regulation and regulatory teaching on strategies for coping with academic stress in undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00022

Feltz, D. L., & Landers, D. M. (1983). The effects of mental practice on motor skill learning and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport Psychology, 5(1), 25–57. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.5.1.25

Guillot, A., Tolleron, C., & Collet, C. (2010). Does motor imagery enhance stretching and flexibility? Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903473828

Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Zourbanos, N., Galanis, E., & Theodorakis, Y. (2011). Self-talk and sports performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(4), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611413136

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kellmann, M., & Beckmann, J. (2017). Sport, Recovery, and Performance. Taylor & Francis Group.

Latinjak, A. T., & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (2020). Self-talk in sport. Applied Network Science, 4(40). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429460623

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half-century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000127

Luthans, K. W., Luthans, B. C., & Palmer, N. F. (2016). A positive approach to management education. Journal of Management Development, 35(9), 1098–1118. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmd-06-2015-0091

Morin, A. (2004). A neurocognitive and socioecological model of self-awareness. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 130(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.3200/mono.130.3.197-224

Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Self-efficacy and human motivation. Advances in Motivation Science, 8(1), 153–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2020.10.001

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. (2011). Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203839010

Tayyab Rashid, & Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). Positive Psychotherapy: Clinician manual. Oxford University Press.

Theodorakis, Y., Weinberg, R., Natsis, P., Douma, I., & Kazakas, P. (2000). The effects of motivational versus instructional self-talk on improving motor performance. The Sport Psychologist, 14(3), 254. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.3.253

Tod, D., Hardy, J., & Oliver, E. (2011). Effects of self-talk: A systematic review. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(5), 666–687. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.5.666

Turner, J. A., Anderson, M. L., Balderson, B. H., Cook, A. J., Sherman, K. J., & Cherkin, D. C. (2016). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic low back pain. PAIN, 157(11), 2434–2444. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000635

Van Raalte, J. L., Vincent, A., & Brewer, B. W. (2016). Self-talk: Review and sport-specific model. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.004

Zimmerman, B. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.