Motivation and emotion/Book/2023/Singing and emotion

What is the relation between singing and emotion?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Music is a powerful tool for influencing emotional responses (Abeles & Chung, 1996), an effect which is suggested by some researchers to be bolstered through the act of singing (see Figure 1; Unwin et al., 2002). People are likely to have been singing long before recorded history (Morley, 2013), and today singing is considered by many to be an important component of emotional expression (Gorzelańczyk & Podlipniak, 2011).

There are a variety of moderators on the relationship between singing and emotion. This chapter considers the multidirectional relationship between singing and emotion, including the emotional basis for why humans sing, the effects of emotion on singing production and communication, and the emotional responses which occur as a result of singing.

|

Focus questions:

|

Understanding emotional responses to singing

[edit | edit source]People have been singing for a very long time, yet it is difficult for researchers to determine when exactly the practice began. Vocal music, unlike instrumental music, does not leave remains and artefacts to be discovered. The earliest recording of musical instruments appears to be around 40,000 years ago (Killin, 2018), however, due to the nature of singing and the lack of physical remains, it is difficult to identify exactly when humans began singing.

Today, singing is found across all human cultures (Unwin et al., 2002), and is considered by some to be a defining feature of human nature (Clift et al., 2008). While there are some common aspects of singing (see Table 1), it can have great variety across cultures, from Tuvan throat singing, to Slavic white voice, to South Indian Konnakol.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Vocal range | The number of pitches a person can sing |

| Vocal type | The classifications of voices based on vocal range, such as soprano, alto and bass |

| Pitch | The audio frequency of a sound; what makes a noise sound higher or lower |

| Intonation | Pitch accuracy; whether someone is ‘singing in tune' |

| Tempo | The speed of a piece of music, often measured in beats per minute |

| Rhythm | Beat patterns and flow within a piece of music |

| Key | The scale which forms the foundation of a piece of music, generally either a major (happy) or minor (sad) key |

| Dynamics | The variation of volume between notes and within a piece of music |

| Consonance and dissonance | Whether simultaneous notes sound pleasant or clashing |

| Lyrics | The words used by singers within a piece of music |

| Melody | The main tune or line within a piece of music; think 'Happy Birthday' |

| Harmony | The supporting tune or line within a piece of music, providing greater depth of sound |

| Timbre | The ‘colour’ or ‘quality’ of a musical sound or voice |

It has been widely demonstrated that music has the capacity to incite strong emotional responses within people (Abeles & Chung, 1996). Yet much of the research has been directed towards emotional responses generated through receptive and passive music listening (Clark & Harding, 2012), rather than through active participation in singing. Unwin et al. (2002) identified that while listening to music altered mood states, the effect was more robust when participants engaged in active singing. Similar results have been demonstrated by other researchers (Clark & Harding, 2012; Grebosz-Haring & Thun-Hohenstein, 2018).

Singing as a method of emotional communication

[edit | edit source]Welch (2005, p. 17) stated that “to sing is to communicate”. While singing is often thought of as primarily an artistic practice, Gorzelańczyk and Podlipniak (2011) suggest that the core function of singing is communicating emotion. While emotions can also be expressed through music more broadly, a singer's emotional experience activates similar emotions in listeners more often than when listening to emotions conveyed through instruments (Gorzelańczyk & Podlipniak, 2011).

Singing allows for both intrapersonal communication as a method of regulating internal representations, self-image and mood, and interpersonal communication with those around us (Welch, 2005). People tend to be able to identify core emotions expressed through song with relative consistency (Schmidt & Trainor, 2010), even from a young age (Trainor & Trehub, 1992). There appears to be some common singing patterns when expressing particular emotions, such as high dynamics when expressing anger, and low dynamics and lack of vibrato when expressing sadness (Scherer, 2017).

While lyrics play a role in the communication of emotion while singing, it may not be as significant to emotional communication as one would expect. In Barradas and Sakka’s (2021) study on the effect of lyrics on emotions in Portuguese and Swedish participants, the presence of lyrics did not affect detections of joy, and only increased detections of sadness in Portuguese participants. This suggests that the presence of lyrics on emotional communication may be mediated by cultural factors. And while Brattico et al. (2011) considered the effect of listening to music rather than the effect of singing, they determined that happy music without lyrics had a stronger positive emotional effect than happy music without lyrics.

|

|

Physiological response to singing

[edit | edit source]Singing has been suggested to have broad physiological effects across multiple systems within the body. This includes lowering blood pressure and heart rate, increasing oxygen saturation levels, and assisting with pain management (Hendry et al., 2022). Singing can reduce physical tension within the body (Clift et al., 2008), and improve both respiratory symptoms and breathing patterns (Clift & Hancox, 2010). It has also been suggested that the well documented emotional benefits of physical exercise could be generated through singing (Clark & Harding, 2012). Specifically, this chapter will consider the hormonal response to singing, the involvement of brain regions and neural pathways, and the influence on facial movements and expression through singing on emotion.

Hormonal and immune response

[edit | edit source]There is a well established relationship between singing and oxytocin. Singing has been shown to increase levels of oxytocin, leading to increased feelings of happiness (Kang et al., 2018). Some studies even suggest oxytocin represents the key physiological link between singing and positive psychological effects (Chanda & Levitin, 2013; Kreutz, 2014). While some recent research suggests this increases in oxytocin may only occur during group, not solo, singing (Good & Russo, 2021), salivary oxytocin has been found to be significantly elevated following singing with others compared to speaking with others (Bowling et al., 2022), suggests some mediating factor of singing on oxytocin production.

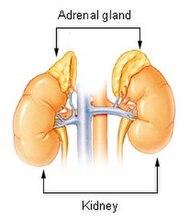

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), is a tropic hormone which stimulates the synthesis and release of cortisol from the adrenal glands (see Figure 2; Grossman et al., 1982), thus likely having an effect on emotional states due to cortisol’s association with stress (Lonsdale & Day 2020). Keeler et al. (2015) found a reduction in ACTH levels in participants following group singing. This finding was bolstered by more recent research; Grebosz-Haring and Thun-Hohenstein (2018) found that participants in an active singing condition had a significantly larger drop in cortisol than participants in a music listening condition, and a significantly higher positive change in feelings of calmness. A reduction in cortisol levels has been found in both group and solo singing conditions (Good & Russo, 2021).

There also appears to be an association between singing and the body’s immune response. A 2018 review of the physiological effects of singing identified an increase in secretory immunoglobulin A (S-IgA) levels as being linked to feelings of more positive emotions (Kang et al., 2018). Singing has been shown to drastically increase S-IgA levels, as much as 240% (Beck et al., 2000). However, a systematic review has suggested that this heightened immune response identified within the literature may not occur as a result of singing, but as a result of being in close proximity to others while breathing energetically and the subsequent increased risk of respiratory infection (Clift et al., 2008).

Neurological involvement

[edit | edit source]Much of the research regarding the neural activation associated with music and emotion relates to passive listening to music, rather than active singing. Despite this, some patterns emerge within the literature. Imaging studies have identified joint activation in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula during experiences of emotions (Morita et al., 2014). Within the context of singing, the ACC and insula have also been associated with emotional vocal control (Grebosz-Haring & Thun-Hohenstein, 2018; Zarate, 2013). Kleber et al. (2007) found there was particularly intense activation in the ACC and the insula during singing, alongside other areas involved with emotional processing such as the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala.

The periaqueductal grey (PAG) is considered to be responsible for the control of emotionally motivated sounds (Unwin et al 2002; Zarate, 2013), with Simonyan and Horwitz (2011) demonstrating that damage to the PAG lead to a loss of emotional pitching in speech. This suggests the PAG may also play a role in emotional singing.

Facial movement

[edit | edit source]A significant aspect of singing involves the movement of facial muscles and the resulting expressions. Singing can involve a variety of facial movements and bodily gestures which create an overall effective experience (Thompson & Quinto, 2011). Welch (2005) even suggests that the visual and facial cues which communicate emotion is the core component of singing. However, it is not simply that the emotion expressed through song can alter facial expressions. The facial feedback hypothesis suggests that the physical experience and sensory feedback of a facial expression influences our emotional experience; smiling makes you happier, while a frown makes you angrier (Soderkvist et al., 2018). This has been supported by a 2019 meta analysis considering over 130 studies of the facial feedback hypothesis, however it noted that the effects tended to be small (Coles et al., 2019).

|

Quiz yourself!

|

Effect of group vs solo singing

[edit | edit source]

Active singing has been shown to elicit a greater emotional response than passive listening to music. But how does singing with others compare to singing by yourself? And what are the resulting emotional effects? Singing with other people can occur over a number of contexts, ranging from group singing around the campfire or at a celebration, to more structured and formal settings such as within a choir.

Choral singing (see Figure 3) is a popular form of singing with others. Choral singing is shown to both increase positive emotions and facilitate emotional expression (Hendry et al., 2022). Choral singing is suggested to produce stronger emotional benefits compared to solo singing (Clark & Harding, 2012; Good & Russo, 2021). Notably, choral singing is suggested to also have greater social bonding and emotional benefits over comparable non-musical group activities (Bowling et al., 2022).

Considering Social Identity Theory, positive emotional effects following choral singing may be due to an increase in self-esteem and positive social identity occurring from participating as a group member. Some research supports this theory within the context of choral singing, with Dingle et al. (2013) demonstrating that choral singing could evoke positive emotions in marginalised populations due to strengthening of a social identity.

Additionally, Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which suggests that autonomy, competence and relatedness drive motivation, has been used by researchers to understand the emotional effects of group singing compared to solo singing. Stewart and Lonsdale (2016) used SDT to assess satisfaction in choral and solo singers, and despite finding similar self-reported scores for competence and relatedness, choral singers reported significantly lower experiences of autonomy. Stewart and Lonsdale (2016) suggested this may occur as a result of choral singers forgoing their need for autonomy when joining a choir, however still remaining satisfied despite this deficit due to the emotional and psychological benefits of belonging to a cohesive group.

|

|

Research applications

[edit | edit source]Researchers have identified that there is a lack of theoretical frameworks (Clift & Hancox, 2010) and empirical research (Clift et al., 2008) within the literature on the relationship between emotion and singing. This is particularly concerning considering the identified potential emotional benefits of singing. In fact, in a systematic review conducted by Clark and Harding (2012), limited support for clinical trials of active singing interventions was found considering the low quality and methodological limitations of the research.

That’s not to say there are no practical applications, as more recent research has identified multiple groups which may receive emotional benefits from group singing interventions. In a group singing intervention for adolescents with mental disorders has been shown to have a positive hormonal and immune response, suggesting emotional benefits (Grebosz-Haring & Thun-Hohenstein, 2018). Perkins et al. (2018) examined the emotional effects of group singing on mothers with newborns, and found enhanced positive emotions following participation, alongside facilitating a sense of achievement. There may also be applications for group singing within marginalised populations such as the elderly or migrants, as choral singing has been shown to evoke positive emotions within these groups (Dingle et al., 2013).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The relationship between singing and emotion is complex; nothing so simple as “if I do x singing technique, I will produce y emotion”. Communication is one of the core functions of singing, with people being able to identify expressed emotion through song from a very young age. Physiologically, explanations for emotional responses to singing focus particularly on oxytocin, cortisol and activation within the ACC. As singing is an act that involves the full body, the facial feedback hypothesis may explain some component of emotional responses to singing. While researchers have criticised the lack of theoretical frameworks available to help understand the implications of emotion and singing, there is some suggestion that group singing interventions may have a positive effect, particularly on those lacking relatedness or a strong social identity.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Music and emotion (Book chapter, 2011)

- Emotion classification (Wikipedia)

- Sad music and emotion (Book chapter, 2017)

- Music and emotion (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Barradas, G. T., & Sakka, L. S. (2022). When words matter: A cross-cultural perspective on lyrics and their relationship to musical emotions. Psychology of Music, 50(2), 650–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211013390

Beck, R. J., Cesario, T. C., Yousefi, A., & Enamoto, H. (2000). Choral singing, performance perception, and immune system changes in salivary immunoglobulin A and cortisol. Music perception, 18(1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.2307/40285902

Bowling, D. L., Gahr, J., Ancochea, P. G., Hoeschele, M., Canoine, V., Fusani, L., & Fitch, W. T. (2022). Endogenous oxytocin, cortisol, and testosterone in response to group singing. Hormones and Behaviour, 139, 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2021.105105

Brattico, E., Alluri, V., Bogert, B., Jacobsen, T., Vartiainen, N., Nieminen, S., & Tervaniemi, M. (2011). A functional MRI study of happy and sad emotions in music with and without lyrics. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(308). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00308

Chanda M. L., & Levitin D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007

Clark, I., & Harding, H. (2012). Psychosocial outcomes of active singing interventions for therapeutic purposes: a systematic review of the literature. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 12(1), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2010.545136

Clift, S., & Hancox, G. (2010). The significance of choral singing for sustaining psychological wellbeing: findings from a survey of choristers in England, Australia and Germany. Music and Health, 3(1), 79–96.

Clift, S., Hancox, G., Morrison, I., Hess, B., Kreutz, G., & Stewart , D. (2010). Choral singing and psychological wellbeing: Quantitative and qualitative findings from English choirs in a cross-national survey. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 1(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.1.1.19/1

Clift, S., Hancox, G., Staricoff, R., & Whitmore, C. (2008). Singing and health: Summary of a systematic mapping and review of non-clinical research. Research Centre for Arts and Health, 1–136.

Coles, N. A., Larsen, J. T., & Lench, H. C. (2019). A meta-analysis of the facial feedback literature: Effects of facial feedback on emotional experience are small and variable. Psychological bulletin, 145(6), 610–651. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000194

Dingle G. A., Brander C., Ballantyne J., & Baker F. A. (2013). ‘To be heard’: The social and mental health benefits of choir singing for disadvantaged adults. Psychology of Music, 41(4), 405–421. https://doi-org/10.1177/0305735611430081

Good, A., & Russo, F. A. (2022). Changes in mood, oxytocin, and cortisol following group and individual singing: A pilot study. Psychology of Music, 50(4), 1340-1347. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211042668

Gorzelańczyk, E. J., & Podlipniak, P. (2011). Human singing as a form of bio-communication. Bio-algorithms and med-systems, 7(2), 79–83.

Grebosz-Haring, K., & Thun-Hohenstein, L. (2018). Effects of group singing versus group music listening on hospitalized children and adolescents with mental disorders: A pilot study. Heliyon, 4(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01014

Grossman, A., Perry, L., Schally, A. V., Rees, L., Kruseman, A. N., & Tomlin, S. (1982). New hypothalamic hormone, corticotropin-releasing factor, specifically stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol in man. Lancet, 319, 921–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91929-8

Hendry, N., Lynam, S., & Lafarge, C. (2022). Singing for Wellbeing: Formulating a Model for Community Group Singing Interventions. Qualitative Health Research, 32(8). https://doi-org/10.1177/10497323221104

Hogle, L. A. (2021). Fostering singing agency through emotional differentiation in an inclusive singing environment. Research studies in music education, 43(2), 179-194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X20930426

Kang, J., Scholp, A., & Jiang, J. J. (2018). A review of the physiological effects and mechanisms of singing. Journal of Voice, 32(4), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.07.008

Keeler, J. R., Roth, E. A., Neuser, B. L., Spitsbergen, J. M., Waters, D. J. M., Vianney, J. (2015). The neurochemistry and social flow of singing: bonding and oxytocin Front. Hum. Neurosci, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00518

Killin, A. (2018). The origins of music: Evidence, theory, and prospects. Music & Science, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059204317751971

Kleber, B., Birbaumer, N., Veit, R., Trevorrow, T., & Lotze, M. (2007). Overt and imagined singing of an Italian aria. Neuroimage, 36, 889–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.053

Koopman, J. (1999). A brief history of singing. Lawrence University.

Kreutz G. (2014). Does singing facilitate social bonding? Music Med 6(2), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.47513/mmd.v6i2.180

Lonsdale, A., & Day, E. (2020). Are the psychological benefits of choral singing unique to choirs? A comparison of six activity groups. Society for Education, Music and Psychological Research, 49(5). https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735620940019

Montagu, J. (2017). How music and instruments began: A brief overview of the origin and entire development of music, from its earliest stages. Evolutionary Sociology and Biosociology, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2017.00008

Morley, I. (2013). The prehistory of music: Human evolution, archaeology, & the origins of musicality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Perkins, R., Yorke, S., & Fancourt, D. (2018). How group singing facilitates recovery from the symptoms of postnatal depression: a comparative qualitative study. BMC psychology, 6(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0253-0

Scherer, K. R., Sundberg, J., Fantini, B., Trznadel, S., & Eyben, F. (2017). The expression of emotion in the singing voice: Acoustic patterns in vocal performance. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 142, 1805–1815. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.5002886

Schmidt, L. A., & Trainor, L. J. (2001). Frontal brain electrical activity (EEG) distinguishes valence and intensity of musical emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 15(4), 487–500, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930126048

Simonyan K., & Horwitz B. (2011). Laryngeal motor cortex and control of speech in humans. Neuroscientist, 17, 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858410386727

Söderkvist, S., Ohlén, K., & Dimberg, U. (2018). How the experience of emotion is modulated by facial feedback. Journal of nonverbal behavior, 42, 129-151.

Stewart N. A. J., Lonsdale A. J. (2016). It’s better together: The psychological benefits of singing in a choir. Psychology of Music, 44, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735615624976

Thompson, W. F., & Quinto, L. (2011). Music and emotion: Psychological considerations. The aesthetic mind: Philosophy and psychology, 357-375.

Trainor, L. J., & Trehub, S. E. (1992). A comparison of infants' and adults' sensitivity to Western musical structure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(2), 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.18.2.394

Unwin, M., Kenny, D., & Davis, P. (2002). The Effects of Group Singing on Mood. Society for Education, Music and Psychological Research, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735602302004

Welch, G. (2005). Singing as communication. Musical Communication. 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198529361.003.0011

Zarate, J. M. (2013). The neural control of singing. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 7, 237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00237

External links

[edit | edit source]- Singing in the brain: neural responses to vocal music (Psychology Today)

- How music affects your baby

- ’s brain (UNICEF)

- Music, emotion, and well-being (Psychology Today)

- How music works: What happens to your brain when you sing (ABC Classic)