Motivation and emotion/Book/2022/Work and flow

What characteristics of work can produce flow and how can flow at work be fostered?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

You will likely relate to both of the following experiences and if not, try to apply them to similar situations:

- You have an assignment due soon and you feel overwhelmed with the task at hand. You set aside a time to do it but find yourself switching between writing a few sentences and mindlessly scrolling on your phone. This lasts for hours on end and any progress you make is slow and unmotivated.

- You click start on your important end-of-semester exam. Though you've studied in the weeks leading up to it, you feel nervous and wired. Before you know it, the two-hour exam has flown by without you even "stopping to think". You emerge from the experience amazed at how "in-the-zone" you became.

The second scenario, emphasising your sense of focus, motivation, and enjoyment, is coined by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (see Figure 1) as the psychological state of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Csikszentmihalyi was a key figure for positive psychology and his flow theory holds practical usefulness in understanding motivation, achievement, and satisfaction across many situations (Beard, 2015).

The main purpose of this chapter is to explore the relationship between flow and work-based activities. This chapter investigates activities that are intellectually-based such as activities existing in workplace and academic settings. Specifically, this chapter aims to explore research surrounding what can produce a flow state during work-based activities.

|

Focus questions:

|

Defining flow

[edit | edit source]Flow is the sensation of optimal experience, produced when engaging in an activity with deep concentration and holistic enjoyment (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). A positive psychology perspective, Csikszentmihalyi (1990) suggests that flow's ability to absorb an individual into the present moment, makes it the answer to living a fulfilling life.

|

Fun fact: When explaining flow, Csikszentmihalyi (1990) warned people not to define flow too specifically, as this could impact the dynamic spirit of flow. |

What are the core elements of flow?

[edit | edit source]Importantly, Csikszentmihalyi (1990) does not describe flow as an uncontrollable sensation and instead, suggests that the experience of flow is accompanied by a list of nine characteristics that can be used to try and promote it (see Table 1). Although these components are commonly present, they are not all essential for flow to occur (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Table 1.

Nine Characteristics of Flow

| Characteristic | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Challenge-skill balance | The task holds an optimal level of challenge |

| 2. | Concentration | Concentration on the task is effortless |

| 3. | Goals | The task has clear and specific goals |

| 4. | Feedback | The task can provide immediate feedback |

| 5. | Engagement | Engagement in the task feels seamless |

| 6. | Control | There is a sense of control over actions |

| 7. | Lack of self-awareness | There is a detachment from any self-awareness |

| 8. | Lack of time perception | Perception of time is weakened |

| 9. | Autotelic experience | There is an autotelic experience |

Note. Adapted from Csikszentmihalyi (1990).

Autotelic experience

[edit | edit source]An autotelic experience is produced from the experience of flow and is seen as the enjoyment component of flow itself (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Therefore, it acts as the intrinsically motivating characteristics of flow that leaves behind a sensation of fulfilment (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). In addition to an autotelic experience, Csikszentmihalyi proposed that an autotelic personality exists, which predisposes an individual to seeking and experiencing states of flow (Baumann, 2021).

How is flow beneficial?

[edit | edit source]Across all activity types, flow is powerful for its capacity to intrinsically motivate an individual, and its typical description of a feeling of enjoyment makes it commonly reported by individuals engaging in leisurely or hobby-related activities (Rheinberg & Engeser, 2018). Click here for more information on flow and leisure.

In line with flow providing a strong motivation for creative activities, Csikszentmihalyi’s initial research surrounded the experience of flow for chess players, rock climbers, and dancers (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009). Csikszentmihalyi (1990) held a strong interest in what motivates an individual to be deeply absorbed in an activity, and this has since evolved into a practical focus on how flow can enhance performance (Harris et al., 2021).

To explore flow’s relationship with performance, Harris et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis, finding a reliable relationship between flow and an increased performance. Despite this, the meta-analysis revealed inconsistencies around the direction of this relationship. Previous flow studies have provided evidence for flow producing increased performance, for increased performance producing the state of flow, and for a two-way relationship existing (Harris et al., 2021). Whilst a relationship appears to exist between flow and increased performance, Harris et al. (2021) highlight the lack of understanding surrounding the relationship’s direction and the mechanisms that impact it. They explain that this is due to the several methodological challenges associated with accurately measuring flow (Harris et al., 2021).

Flow and work-based activities

[edit | edit source]Although the majority of flow experiences have been recorded from hobbies and leisurely activities, flow also occurs in work settings and this is an important area of flow research due to the potential for enhanced performance (Rheinberg & Engeser, 2018). Interestingly, some research even suggests that flow is easier to experience during work-based activities, rather than leisurely-based, due to the structured and goal-based nature of work-based tasks (Ceja & Navarro, 2011).

Workplace settings

[edit | edit source]

Ceja and Navarro (2011) define flow as an essential component for workplace wellbeing, healthy functioning, and high achievement (see Figure 2). Employee wellbeing is a highly researched area, forming interest around the growing research suggesting that flow increases employees' happiness, motivation, and performance levels (van Oortmerssen et al., 2020).

A systematic review by Yan and Donaldson (2022) investigated whether differences exist between the related concepts of workplace engagement and the experience of flow. Their findings suggest that in the workplace, flow interventions can produce greater results than general workplace engagement interventions (Yan & Donaldson, 2022). Alongside these findings, Yan and Donaldson (2022) criticise workplace flow research for focussing on the outcomes, rather using evidence-based processes to explore the experience of it.

| Case study:

Chloe has a really important proposal to present at her work meeting. Although she has been practicing for a fortnight, she feels nervous as she recognises the pressure for her boss to accept her idea. As she begins presenting, she finds herself deeply present and focussed whilst also feeling distant from any unrelated thoughts. Chloe experiences a state of workplace flow, with many of Csikszentmihalyi’s nine elements present. Can you list which ones? |

Academic settings

[edit | edit source]

Li et al. (2022) explain that it is highly desirable for students to enter a flow state while learning to improve their concentration and their sense of control (see Figure 3). In addition, it can lead to improved motivation levels and greater academic performance (Li et al., 2022).

Tarling (2016) highlights that this is because being in a flow state is a natural part of the learning process, allowing students to challenge themselves whilst feeling enjoyment and fulfilment. This can be linked to the 1978 learning theory of the zone of proximal development, arguing a similar concept to flow’s challenge-skill balance for providing the best environment for students to learn in (Tarling, 2016). Importantly, a study by Ro et al. (2018) that likewise supports that flow improves students’ learning experiences, also highlights that it is difficult to define any direct links due to the dynamic nature of flow and of learning environments.

|

Test yourself

Choose the correct answer and click "Submit":

|

What characteristics of work can produce flow?

[edit | edit source]Research has shown that the experience of flow itself is described consistently across socioeconomic class, gender, age, culture, and activity type, however, that the conditions producing flow can vary strongly across individuals (Ullen et al., 2012). Despite evidence for differences across individuals, Csikszentmihalyi’s nine characteristics of flow can be broken up into general antecedents, sub-dimensions, and consequences (Li et al., 2022). From these dimensions, the general antecedents of flow are said to be (Li et al., 2022):

- A challenge-skill balance

- Having clear goals

- Having access to clear feedback

Workplace settings

[edit | edit source]Ceja and Navarro (2011) conducted a study to assess workplace flow over time. Their findings support that variability exists amongst flow-producing factors, arguing that flow in the workplace is unpredictable over time due to changes in employees’ optimal work experiences (Ceja & Navarro, 2011).

Fortunately, their findings do illustrate the ability to increase flow experiences through small interventions, such as clarifying the task’s objectives, providing daily social support, ensuring skill variety, and linking the importance of work tasks to non-work tasks (Ceja & Navarro, 2011). In addition to specific interventions, Ceja and Navarro’s (2011) findings also suggest the role of employee’s work structure. Specifically, individuals with a full-time job contract and structured working schedule (having set workdays and hours) seem to experience a flow-promoting environment (Ceja & Navarro, 2011).

From these findings, Ceja and Navarro’s (2011) main argument is that workplace flow is still healthy and beneficial when experienced dynamically over time and therefore interventions to promote long-term flow should be continually reassessed across each individual and situation.

To further explore flow antecedents, a study by Rheinberg and Engeser (2018) revealed both supportive and unsupportive factors of workplace flow.

From these findings, supportive factors included:

1. Being given complicated or new tasks

2. Using the computer

3. Learning new knowledge

(Rheinberg & Engeser, 2018).

Whereas unsupportive factors included dealing with (see Figure 4):

1. Constant interruptions

2. Restrictive deadlines

3. A negative environment

(Rheinberg & Engeser, 2018).

Further contributing to workplace flow research, Kawalya et al. (2019) looked at nurses working in a Ugandan hospital. Their results suggest that a match between employees’ assigned work and their individual strengths is the essential antecedent for flow (Kawalya et al., 2019). This aligns with Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) challenge-skill balance antecedent, and this flow dimension will be further explored below. Encouragingly, Kawalya et al. (2019) also found a significant and positive relationship between flow experience and workplace happiness.

|

Test yourself

Choose the correct answer and click "Submit":

|

Academic settings

[edit | edit source]A study by Joo et al. (2012) investigated the flow-promoting factors during e-learning, revealing the role of an individual’s self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and perceived usefulness of the learning task. Of these characteristics, perceived usefulness is the only external factor which can be influenced (Joo et al., 2012). This suggests that within academic settings, learning tasks can be created to be relevant and valuable to the students and therefore, increase the likelihood of students entering a flow learning state (Joo et al., 2012). Suggesting similar controllable factors as Joo et al. (2012), a study by Tarling (2016) indicates that students experience flow when they are engaged in goal-focussed and practical tasks that reflect real-life situations.

To further explore external and controllable factors for academic flow, Ro et al. (2018) found that increased flow experiences led to higher academic results. To induce flow, Ro et al. (2018) suggest the importance of creating an overall positive learning environment, as well as the specific incorporation of:

1. Concept-oriented games

2. Real-life simulations

3. Competitive games

4. Learning projects

Importantly, flow-restricting factors were also highlighted within the research. Tarling's (2016) findings revealed that only 50% of students had been able to experience flow in a classroom environment, due to the distracting nature of a classroom. In addition, in line with findings by Joo et al. (2012), a study by Wagner et al. (2020) similarly emphasised the role of fixed personality traits for producing academic flow. Specifically, that academic flow is more easily fostered by those with personality traits of creativity, judgement, love of learning, zest, hope, self-regulation, and perseverance (Wagner et al., 2020).

Research suggesting the challenge-skill balance

[edit | edit source]

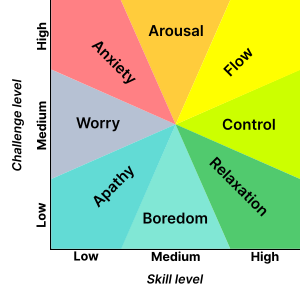

Fong et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis on flow research and argued that the central flow antecedent is the challenge-skill balance. As seen in Figure 5, a flow state can occur when there is a match between a high-challenge task, and a highly-skilled individual (Fong et al., 2015). This makes sense, as a key component of flow is that the individual feels optimally challenged and simultaneously, confident in their abilities (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Fong et al. (2015) emphasise the challenge-skill element for its practicality and thus its potential links to increasing work-based performance.

Importantly, Fong et al. (2015) highlight that separate factors can play a moderating role in this relationship between the challenge-skill balance and flow being produced. For example, age, culture, individual differences in achievement motivation, high ability, high talent, and having an autotelic personality (Fong et al., 2015).

Whilst their meta-analysis does suggest that the challenge-skill balance is the most important element, Fong et al. (2015) additionally cite research that has shown a relationship between the challenge-skill balance and flow, as low as a 2-4% impact. This is further emphasising issues with moderating factors, as well as variability across individuals and situations (Fong et al., 2015).

| Case study:

Josh has worked as a retail assistant for six months and has grown confident handling a variety of phone-call issues. Normally, he is told to pass considerably difficult complaints over to his boss. Today, an angry customer calls to complain and Josh is challenged by his boss to resolve the issue by himself. Although Josh is highly challenged by the customer’s concerns, this is balanced with his extensive product knowledge and his strong confidence for communicating with customers via the phone. Josh experiences a challenge-skill balance and excels on the phone call. |

Critical analysis and future research

[edit | edit source]As this chapter has explored there are several limitations surrounding antecedents of flow research within work-based settings, and these limitations go beyond Ceja and Navarro’s (2011) concerns of high variability amongst and within individuals.

Fong et al. (2015) highlight issues with boredom and lack of engagement that exist in both workplace and academic settings. In addition, the compulsory nature of activities in workplace and academic settings is mismatched against the intrinsically motivating nature of flow (Fong et al., 2015). Further, Li et al. (2022) highlight the issues surrounding successfully measuring flow and isolating other potentially contributing factors.

Future research directions

[edit | edit source]In addition to highlighting a need for more general research around flow antecedents across different contexts and populations, the research offers some specific suggestions:

1. Ceja and Navarro (2011) suggest the need for further study surrounding the impacts of job contracts (e.g., full-time versus part-time), amount of flexibility in working schedule, age, and job tenure in producing a state of workplace flow.

2. Ceja and Navarro (2011) found that successfully experiencing flow in the workplace has high variability over time, suggesting that future research explores participants’ flow patterns across time.

3. Tarling (2016) emphasises the opportunity that flow provides for improving school curriculums and suggests investigation into the effects of educating students on both what a flow state is and its potential benefits.

4. van Oortmerssen et al. (2020) stress the need for future studies to utilise experimental designs that can strengthen our ability to define causal relationships.

5. Yan and Donaldson (2022) highlight that whilst research promotes the use of workplace flow interventions to increase performance and wellbeing, that this should be studied against participants with an already high level of work engagement to see if it can be further increased.

Interesting new research

[edit | edit source]Whilst it is established that general further research is needed, Li et al. (2022) raise concerns around whether studies are adequately measuring flow. Specifically, due to flow mainly being measured through self-report methods (Li et al., 2022).

Fortunately, Li et al. (2022) then describe more recent research around flow's connection to neural pathways. This stimulates exciting further research avenues which could help to further define the state of flow, whilst exploring whether flow can be stimulated through nervous system activation. Li et al. (2022) have established their own research in this area and conducted a flow-recording experiment based upon participants’ heart rate variability data (see Figure 6).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) flow theory provides valuable insight for intrinsic motivation, wellbeing, achievement, and satisfaction, making it highly relevant for work-based activities. Flow theory is comprised of nine core elements, three of which are proposed by Csikszentmihalyi (1990) to act as antecedents for the experience of flow: challenge-skill balance, clear goals, and clear feedback. Due to flow holding practical implications for fostering both work-based wellbeing and increased performance, flow research has continued to develop. This has raised important questions around how flow can be produced, and research continues to develop specific strategies for workplace and academic environments based on Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) three antecedents. Of these, there is evidence that the leading antecedent is the challenge-skill balance (Fong et al., 2015). Alongside these advances in understanding how to foster flow, research importantly highlights several challenges surrounding adequately measuring flow across time, individuals, and contexts, isolating other potentially contributing factors, and the role that fixed personality traits may play.

| Three take home messages:

1. Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) nine characteristics suggest three flow antecedents: a challenge-skill balance, clear goals, and access to clear feedback. 2. Developing research around work-based flow is suggesting specific flow-producing factors for both workplace and academic contexts. These factors are based on Csikszentmihalyi's (1990) three antecedents and the challenge-skill balance is most commonly emphasised. 3. A mutual consensus exists across studies that more research is needed to continue refining our knowledge around consistently producing work-based flow across time, individuals, and contexts. |

See also

[edit | edit source]- The autotelic personality (Book chapter, 2019)

- Flow (Book chapter, 2011)

- Leisure and flow (Book chapter, 2019)

- Mastery and flow (Book chapter, 2015)

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Beard, K. S. (2015). Theoretically speaking: An interview with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi on flow theory development and its usefulness in addressing contemporary challenges in education. Educational Psychology Review, 27, 353–364. https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1007/s10648-014-9291-1

Ceja, L., & Navarro, J. (2011). Dynamic patterns of flow in the workplace: Characterizing within-individual variability using a complexity science approach. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(4), 627–651. https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1002/job.747

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper and Row.

Fong, C. J., Zaleski, D. J., & Leach, J. K. (2015). The challenge-skill balance and antecedents of flow: A meta-analytic investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.967799

Harris, D. J., Allen, K. L., Vine, S. J., & Wilson, M. R. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between flow states and performance. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1929402

Joo, Y. J., Yon, L. K., & Mi, K. S. (2012). A model for predicting learning flow and achievement in corporate e-learning. Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 313–325.

Kawalya, C., Munene, J. C., Ntayi, J., Kagaari, J., Mafabi, S., & Kasekende, F. (2019). Psychological capital and happiness at the workplace: The mediating role of flow experience. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1685060

Li, M. X., Nadj, M., Maedche, A., Ifenthaler, D., & Wohler, J. (2022). Towards a physiological computing infrastructure for researching students’ flow in remote learning. Technology, Knowledge, and Learning, 27, 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-021-09569-4

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. In C. R. Synder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 195–206). Oxford University Press.

Rheinberg, F., & Engeser, S. (2018). Intrinsic motivation and flow. Motivation and Action, 579–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65094-4_14

Ro, Y. K., Guo, Y. M., & Klein, B. D. (2018). The case of learning and flow revisited. Journal of Education for Business, 93(3), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2017.1417229

Tarling, J. (2016). Could flow psychology change the way we think about vocational learning and stem the tide of poor wellbeing affecting our students? Ask the students, they’ll tell you. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 21(3), 302–305. https://doi-org.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/10.1080/13596748.2016.1195171

Ullen, F., Manzano, O. D., Almeida, R., Magnusson, P. K. E., Pederson, N. L., Nakamura, J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Madison, G. (2012). Proneness for psychological flow in everyday life: Associations with personality and intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.003

van Oortmerssen, L. A., Caniels, M. C. J., & van Assen, M. F. (2020). Coping with work stressors and paving the way for flow: Challenge and hindrance demands, humor, and cynicism. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 2257–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00177-9

Wagner, L., Holenstein, M., Wepf, H., & Ruch, W. (2020). Character strengths are related to students’ achievement, flow experiences, and enjoyment in teacher-centered learning, individual, and group work beyond cognitive ability. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01324

Yan, Q., & Donaldson, S. I. (2022). What are the differences between flow and work engagement? A systematic review of positive intervention research. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2036798

External links

[edit | edit source]- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Claremont Graduate University)

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi: Flow, the secret to happiness (YouTube)

- What is Flow Theory? What does this mean for our students? (YouTube)