Motivation and emotion/Book/2021/Morality as a psychological need

What is morality and what are its implications as a psychological need?

Overview

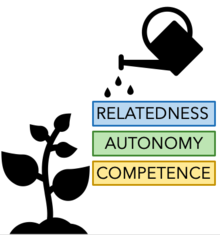

[edit | edit source]Autonomy, competence, and relatedness are the three components of psychological needs. These needs outline the essential psychological conditions within organisms that provide well-being, growth, and life. However, has the scope of psychological needs been too narrow?

This chapter explores morality, as well as its implications of being a psychological need. This exploration will be achieved by addressing the following questions:

1. What is morality?

2. What are psychological needs?

3. What are the implications of morality as a psychological need?

Philipa Foot’s “Trolley dilemma” is a simple yet effective introduction to morality (seen in fig. 1). Imagine that a train is heading towards five railway workers that are soon to be run over. However, before the five workers, is a divergent track in which a single worker is present. You are placed at a switch that can divert the train from the five workers, therefore, killing the single worker. Would you pull the switch?

What is morality?

[edit | edit source]Morality has been present since the origins of humankind. Subsequently, like the species it resides in, morality has changed throughout time. “What is morality?” is a question that can be answered by analysing its development. This section will provide brief overviews of morality’s evolutionary origins, ancient moral theory, morality’s shift from philosophy, and moral psychology.

Evolutionary origins

[edit | edit source]

The origin of morality extends well into the past. As a result, evolutionary psychology has played a vital role in understanding the fundamental basis of morality. Although it may sound paradoxical, self-interest, or individual intentionality, is believed to be the source of human morality. Individual intentionality means to only be concerned for one’s own well-being, and can be observed in many animal species, most notably through the activity of food gathering. After many thousands of years, individual intentionality evolved into joint intentionality (seen in fig. 2). Cooperation became a necessity for early human ancestors as they began hunting larger, and therefore, more challenging sources of food. This cooperation leads to a new moral perspective of disregarding one’s self-interest for the sake of a common goal. Then again, many years later, human morality began to shift with the development of culture. Joint intentionality led to collective intentionality as tribes became distinguishable through their conventions and norms. These conventions and norms became internalised by tribe members, and subsequently created a sense of right and wrong.

Ancient moral theory

[edit | edit source]The next notable stage of morality’s development is in ancient philosophy. Ancient philosophy displays humankind’s initial attempt to understand morality. However, the scope of work done during this time was narrow, and equated morality to being about the soul, happiness, and virtue. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, were philosophers that provided substantial contributions to the area.

Morality's shift from philosophy to psychology

[edit | edit source]Morality remains, to this day, a prevalent topic within Philosophy; however, an additional exploration of the concept was created by the field of psychology. Frank Chapman Sharp conceived the idea of empirically studying morality and, as a result, the line between philosophical morality and psychological morality became more distinct. For example, within philosophy, ethics and morality are commonly seen as interchangeable terms. However, psychology quickly stressed the importance of their separation. Psychology defined ethics as one’s sense of right and wrong in accordance with an outside group. This is in contrast to morality, which is one’s sense of right and wrong in accordance with the self.

Moral psychology

[edit | edit source]Today’s view of moral psychology emerged due to increasing empirical research surrounding the concept. Research began to empirically explore, and subsequently theorize the many aspects of morality. Such aspects include moral reasoning, moral development, moral behaviour, moral identity, and so on. A commonly known example within this field is Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development (1958). Inspired by, and building on, Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development (1936), Kohlberg outlined cognitive developmental levels in which morality is developed.

What are psychological needs?

[edit | edit source]

Psychological needs are a concept drawn from the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which attempts to theorise human motivation. SDT dissects motivation into intrinsic and extrinsic categories; furthermore, the theory outlines motivation’s effect on both social and cognitive development. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness, are theorised to be the three areas that determine one’s motivation (seen in fig. 3). These three areas are commonly referred to as psychological needs. When one’s psychological needs are satisfied, their motivation will be high in quality; however, motivation can also lessen in quality if one’s psychological needs are not satisfied.

Implications of morality as a psychological need

[edit | edit source]As research of morality has progressed, implications of it being a psychological need have appeared. This chapter explores the implications of morality as a psychological need by analysing how morality satisfies the established psychological needs criteria, SDT and morality’s intersections, and morality as an important human motive and trait.

Criteria for establishing a psychological need

[edit | edit source]Baumeister and Leary (1995), created a criteria for establishing a psychological need. In essence, the criteria deconstructs the defining aspects of autonomy, competence, and relatedness into a checklist and; as a result, nine core characteristics were created. By utilising the checklist, researchers can systematically test whether suspected concepts fundamentally match that of a psychological need. A study by Sheldon et al. (2001), provided a simple outline of the logic behind the criteria. The outline consisted of two parts, the first being that peak experiences will equate to the most satisfying needs. This logic can be restated to say that events are satisfying as a result of satisfied psychological needs. The second part is that well-being is promoted through need satisfaction. Therefore, when these two parts are combined, when a tested concept promotes well-being and provides satisfaction from events, it passes the criteria.

Prentice et al. (2018), rigorously tested whether morality satisfied the criteria for establishing a psychological need. The test consisted of four studies; within these studies, participants were questioned about recent negative and positive events. Participant’s need satisfaction and morality’s satisfying/thwarting dynamic, during these events, was assessed. Proceeding this step, the assessed dynamic was compared with a quantified responsiveness to each need. Furthermore, the prolific, affective, and productive criteria, is approached by examining the well-being consequences of moral need satisfaction.

Although the first two studies measured the same variable, they differed in the category of participants; study 1a. Amazon’s mechanical turk, and study 1b. students. The first measure of the test was recent peak life events, which was determined by four experiences participants considered the most meaningful, pleasurable, satisfying, and unsatisfying. The second measure of the test was psychological needs. Psychological needs were measured by participants rating the satisfaction of autonomy, relatedness, security, self-esteem, and competence in relation to the four events. In addition, five items assessing moral need were included. The final measure, well-being and satisfaction, was conducted by the means of a flourishing scale.

The results across the two studies obtained identical findings. When compared to the five measured psychological needs, morality was never lower, and was commonly more satisfied during the events. The first implication from the results is that the participants used morality to identify peak life events. The second implication was the appropriateness of comparison between morality and the psychological needs. Lastly, implications of morality’s impact on well-being were outlined.

The final two studies reflected the same differentiation of categories of participants. However, the last two studies measured five variables. The first measure was a moral trait scale completed by participants. The second measure reflected the first two studies of the five events chosen by participants; although, for each event, participants had to choose two events of each category based on whether they had acted at their worst, and best. The third measure was psychological needs, and consisted of ten needs which added money, self-acceptance/meaning, pleasure, physical thriving/meaning, and power, to the initial two study’s list of measured needs. The fourth measure was participants' well-being during the event. The final measure was participants' current well-being.

The results of the study displayed morality’s performance as consistently equal to, or greater than the psychological needs. To elaborate, morality was experienced more than any other need when participants were at their best; additionally, morality was seen as being thwarted during unsatisfying events. Morality had also drawn implications for the well-being of participants both during and out of the events.

All four studies gathered results implying morality’s satisfaction of establishing a psychological need criteria. It was demonstrated that morality directs cognitive processing, has affective consequences, is distinctive from other needs, and can support relevant research within the area, for example, beneficence as a psychological need. This research serves as a foundation in which moral research can be built on.

Self-determination theory and morality's intersections

[edit | edit source]Although moral research has implied its presence within SDT, the areas remain distinct. However, evidence outlining intersections between SDT and morality continue to grow. These intersections arise due to SDT’s inability to be dissected into a few basic principles. Rather, the theory is a framework composed of a potentially endless amount of mini-theories. Today, the six-mini theories that are recognised are Organismic Integration Theory, Cognitive-Evaluation Theory, Causality-Orientations Theory, Goal Contents Theory, Relationship Motivation Theory, and Basic Psychological Needs Theory. Although the mini-theories share the same fundamental ideas, they differ in the phenomena they attempt to explain.

Basic psychological needs theory and morality

[edit | edit source]The first mini-theory that intersects with morality is the Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT). BPNT is focused on explaining the link between psychological needs and psychological health and well-being. Furthermore, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, can be used to predict one’s psychological health and well-being. This prediction is based on whether the needs are being either satisfied or thwarted.

The intersection of BPNT and morality revolve around the finding that satisfaction of the psychological needs is essential to well-being (Chirkov et al, 2005). Although, the satisfaction of psychological needs cannot be attained without achieving moral understanding, capabilities, and virtue (Curren, 2013; Ryan et al., 2013). For example, self-endorsed moral motivation can greatly impact autonomy. In addition, in the context of learning, moral motivation is more self-sustaining compared to mastery motivation (Weinstein & Ryan, 2010).

Organismic integration theory and morality

[edit | edit source]The second mini-theory that intersects with morality is the Organismic Integration Theory (OIT). OIT focuses on theorising extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation consists of multiple instrumental subtypes which fall upon an internalisation continuum. The extent of internalisation of an extrinsic motive equals the extent of autonomy experienced by the person. Furthermore, OIT attempts to explore what it is that causes internalisation.

The intersection of OIT and morality occurs within the context of internalisation. It is widely believed that autonomous moral motivation is learned through life; however, there is research to suggest that this is incorrect. Infants have been shown to offer spontaneous help to others without being asked and without being offered a reward (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006); this finding implies the possibility of morality being innate (seen in fig. 4). In addition, infants at the age of 15 months prefer equal over unequal allocation of resources (Sommerville & Ziv, 2018); these studies display that autonomous motivation for moral action is not all-or-nothing (Krettenauer & Curren, 2020).

Morality as an important human motive, and trait

[edit | edit source]Morality as an important human motive has experienced a recent rise in popularity with empirical testing. Read et al.’s (2010) study, forced participants to sort 161 motives into groups. An analysis of results provided broad clusters of motives, these being relatedness, religion, self-enhancement/self-knowledge, avoidance, and morality. This analysis displays the cognitive importance of morality in terms of human motives.

Implications of morality within self-affirmation have also been discovered. Self-affirmation is a process which occurs in order to restore one’s self-perception. When the perceived integrity of the self is threatened, rationalisation, explanation, and/or action occur to achieve restoration. Research by Steele (1988) proposed that the process of self-affirmation occurred to maintain a morally and adaptive adequate self-conception.

Morality has additionally been seen to impact Religiosity. Zhong & Liljenquist’s ‘Washing Away Your Sins’ (2006), focused on the practise of physical cleansing in religious ceremonies (seen in fig. 5). The practice infers a psychological association between moral purity and bodily purity. Subsequently, the study explored cleanliness in response to moral impurity. Results showed that moral impurity caused an increased desire in cleansing products, and greater mental accessibility of cleansing-related concepts. In addition, physical cleansing reduces upsetting consequences of immoral behaviour, and alleviates threats to one’s moral self-image.

Finally, research has also explored morality as a human trait. Zeinoun et al. (2017) reduced personality traits down to 167 items. Following this, 806 participants sorted the traits into categories. Results displayed five top level categories, these being dominance, conscientiousness, emotional stability, agreeableness/righteousness, positive emotionality, and morality. This study implies that morality may extend beyond the area of motivation, and could additionally serve as a trait.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Morality is a concept extending well into humanity’s past; however, a recent empirical shift has drastically improved our knowledge of the concept. As our knowledge continues to grow, implications of morality have become present in relevant fields of research, such as, psychological needs. These implications arise as morality has displayed the capacity to satisfy the establishing a psychological need criteria, intersections between SDT and morality have surfaced, and morality’s significant impact in the fields of human motives, and traits has been discovered. These findings not only help us define the concept of morality, but serve as an important foundation for its implication as a psychological need.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Basic psychological need theory (Book chapter, 2020)

- Beneficence as a psychological need (Book chapter, 2021)

- Dark triad and personality (Book chapter, 2021)

- Frustration of basic psychological needs (Book, chapter, 2021)

- Morality and emotion (Book, chapter, 2020)

- Religiosity and coping (Book chapter, 2022)

- Self-determination theory (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological bulletin, 117(3), 497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Chirkov, V. I., Ryan, R. M., & Willness, C. (2005). Cultural context and psychological needs in Canada and Brazil: Testing a self-determination approach to the internalization of cultural practices, identity, and well-being. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 423-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275960

Curren, R. (2013). Aristotelian necessities. The good society, 22(2), 247-263. https://doi.org/10.5325/goodsociety.22.2.0247

Krettenauer, T., & Curren, R. (2020). Self-determination theory, morality, and education: introduction to special issue. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2020.1794173

Prentice, M., Jayawickreme, E., Hawkins, A., Hartley, A., Furr, R. M., & Fleeson, W. (2019). Morality as a basic psychological need. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(4), 449-460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618772011

Read, S. J., Talevich, J., Walsh, D. A., Chopra, G., & Iyer, R. (2010, September). A comprehensive taxonomy of human motives: A principled basis for the motives of intelligent agents. In International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents (pp. 35-41). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15892-6_4

Ryan, R. M., Curren, R. R., & Deci, E. L. (2013). What humans need: Flourishing in Aristotelian philosophy and self-determination theory. https://doi.org/10.1037/14092-004

Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Kim, Y., & Kasser, T. (2001). What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.325

Sommerville, J. A., & Ziv, T. (2018). The developmental origins of infants’ distributive fairness concerns. Atlas of moral psychology, 420-429. Retrieved from: https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=qrk8DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA420&dq=The+development+of+origins+of+infants%E2%80%99+distributive+fairness+concerns&ots=MOfqR7zHPG&sig=mhXVcEdu0NrTC07EFuvUbXxTurk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=The%20development%20of%20origins%20of%20infants%E2%80%99%20distributive%20fairness%20concerns&f=false

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 261-302). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60229-4

Tomasello, M (2018). The Origins of Morality. ScientificAmerican. Retrieved from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/index.cfm/_api/render/file/?method=inline&fileID=B6F43AF2-ECFB-4378-BDBD06B32335474F

Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science, 311(5765), 1301–1303. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1121448

Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016984

YI, X. M., & ZHAO, J. B. (2006). Subjects in Morality Internalization. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences), 5. Retrieved from: https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-BJSF200605014.htm

Zeinoun, P., Daouk‐Öyry, L., Choueiri, L., & van de Vijver, F. J. (2018). Arab‐levantine personality structure: A psycholexical study of modern standard Arabic in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and the West Bank. Journal of personality, 86(3), 397-421. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12324

Zhong, C. B., & Liljenquist, K. (2006). Washing away your sins: Threatened morality and physical cleansing. Science, 313(5792), 1451-1452. 10.1126/science.1130726

External links

[edit | edit source]- Monkeys and morality (Crash Course Psychology #19, YouTube)

- Science can answer moral questions | Sam Harris (TED, YouTube)

- The Problem of Evil (Crash Course Philosophy #13, YouTube)

- Would you sacrifice one person to save five? - Eleanor Nelsen (TED-Ed, YouTube)