Motivation and emotion/Book/2021/Empathy-altruism hypothesis

What is the empathy-altruism hypothesis and how can it be applied?

Overview

[edit | edit source]A common trait that is seen and heard every day is altruism, whether it is a news story about a good Samaritan helping a person or animal from danger, a worker sharing their meal with a co-worker who forgot their lunch, or helping a loved one with a problem. There are many speculations and theories about why humans are altruistic, but one perspective that has been well researched is the empathy-altruism hypothesis (EAH). The EAH is an educated idea that the emotional state of empathy motivates altruism.

|

Focus questions:

|

The empathy-altruism hypothesis

[edit | edit source]

What is the empathy-altruism hypothesis?

[edit | edit source]The empathy-altruism hypothesis (EAH) is a motivational theory which investigates why humans can perform acts that are purely recognised as helping another reach a satisfying state of wellbeing. The EAH is often discussed by examining empathy and altruism separately. This is because the EAH is one of many theories of motivation, with similar theories such as the social exchange theory and empathic-joy hypothesis competing to explain why humans are compelled to help others when there is no obvious reward. It is vital to understanding the importance of the key terms of EAH and why it is regarded as a hypothesis and not a theory or fact.

Key terms

[edit | edit source]The EAH, as illustrated by Batson (1987) describes that “empathic concern produces altruistic motivation” (Batson et al., 2015, p. 1). The EAH is better understood by unpacking:

- what is meant by empathic concern and

- what is meant by altruistic motivation.

Empathy

[edit | edit source]

Empathy is a cognitively complex emotion that allows a person to understand another individual, usually from perspective taking and emotions such as compassion and tenderness (Batson et al, 2015 & Reeve, 2018). Modern researchers classify empathy into two parts; cognitive empathy and emotional empathy (Reeve, 2018). Cognitive empathy involves understanding another’s feelings by reducing one’s own perspective to account for the perspective of the other. Emotional empathy involves “other focused feelings” (Reeve, 2018, p. 358) such as compassion, concern, sympathy and tenderness (see Figure 1). Most people use both aspects of empathy and don’t usually use one more than the other (Reeve, 2018). Empathy is very similar to empathic concern, where in both cases, an individual can empathise with another, however, empathic concern involves an extra level of congruence and positive regard.

Altruism

[edit | edit source]Altruism at its core, is a behaviour where an individual acts selflessly with the ultimate goal of helping another and promoting their welfare (Batson et al., 2015; Greater Good, n.d.). Altruism is investigated heavily in social psychology as it is one of the few traits that displays selfless instead of selfish effects (Cherry, 2021). There are two forms of altruism; evolutionary altruism and psychological altruism. Evolutionary altruism examines the cost of oneself acting in a way that puts them at risk, but benefits the survival of others and giving them a better chance to pass on genes (Batson et al., 2015; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2013 & Taylor, 2010). Psychological altruism, in contrast, is the desire to reach an “ultimate goal of increasing another’s wellbeing” (Batson et al., 2015, p. 3) without thinking about self-interest (Taylor, 2010). However, altruism doesn’t have to be a method of complete selflessness. As Batson et al. (2015) explain, modern researchers class altruism as a form of egoism, with the goal of receiving an internal reward for helping another reach an appropriate state of wellbeing. (This will be discussed in more detail under Motivation and reward).

Hypothesis

[edit | edit source]Additionally, it is crucial to understand why it is a hypothesis, not a fact or theory. A hypothesis is a limited scientific idea or assumption that is used as a starting point for identifying or guessing scientific phenomena that is not yet proven (Bradford, 2017b; Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Hypotheses differ from facts, theories and laws as they do not attempt to explain certain factors or reasoning, but instead form a possible idea that can be tested, theorised and researched, which may lead to finding possible answers (Bradford, 2017b; Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

Why is the empathy-altruism hypothesis relevant?

[edit | edit source]A common question about any theory, fact, law or hypothesis is ‘why is it relevant?’. There are reasons behind many physiological and psychological mechanisms regarding the human body, such as the sympathetic nervous system, which regulates the flight-or-fight response, or laughter, which helps to make and maintain social bonds. The EAH is relevant for a number of reasons, including a decrease in fickle help, decreased aggression and increased cooperation in conflicting situations.

Increase in sensitive help, decrease in fickle help

[edit | edit source]Studies investigating the EAH often find positive correlations between the level of empathy and the level of altruistic motivation involved. As Batson et al. (2015) explains, the more empathetic we are towards an individual, the more likely we are to help. Furthermore, experiments tested by Batson et al. (1981, 1988) found that people with lower signs of empathy expressed, resulting in a stronger mindset of egoism, were more likely to escape the situation (see Table 1 for a simple comparison) of seeing another in need of help, if the option of escape was easy (Batson et al.,2015).

Decrease in aggression and derogation

[edit | edit source]Aggression and acts of violence typically negatively affect another’s wellbeing, which can inflict fear and sadness onto the recipient. This conclusion, made by Batson et al. (2015) emphasises the importance of empathy-induced altruism as a means of not making another’s wellbeing any worse than what it already is, and therefore should reduce the inhibition of aggression. Numerous older studies investigated the effects of aggression and derogation towards specific minority groups. Significant studies performed by Melvin Lerner and William Ryan highlighted the rate of derogation towards certain minority groups (Batson et al., 2015). The rates, which were rather high, implied that it is common for people to unconsciously blame those individuals or groups of people for the discrimination that they receive. As Batson et al. (2015) explains however, the EAH as expected, somewhat counteracts derogative and aggressive behaviour through the use of perspective-taking and wanting to help the targeted individuals reach a desirable state where they aren’t to blame.

Increase in cooperation

[edit | edit source]When a conflict arises, no matter if it is a political debate, business argument or a financial dispute, the first action is for oneself to begin by using egoism in an effort of self-interest. This is a common path to take as no one wants to be left with a negative outcome. Thus, Batson et al. (2015) and numerous others (Batson & Moran, 1999; Klimecki, 2019) have conducted studies which identify the benefits of cooperation and strengthen the idea of empathic-inspired altruism as a key type of altruistic motivation in both theoretical and real situations. Results from these studies suggest that although the EAH does have a positive effect on cooperation, dispute resolution is not drastically improved. However, implementing empathic behaviours such as perspective-taking improves the probability of empathy helping participants reach a mutually beneficial outcome (Batson et al., 2015; Batson & Moran, 1999). Overall, there are numerous reasons as to why the EAH is relevant to humans in every day life. There is more depth to unpack, specifically the applications of the EAH.

|

Case Study- Segregating children based on eye colour On Friday April 5th 1968 (the day after Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated.), Jane Elliott, a North American primary school teacher performed an interesting experiment on her students. This experiment, known as the blue eyes/green eyes exercise, effectively taught her students how segregation worked. In this exercise, Elliott separated students with blue eyes and students with green or brown eyes. Elliott continued by saying “the brown-eyed people are better people in this room ... they are cleaner and they are smarter” (Bloom, 2005, para. 4) throughout the day. Elliott continued this kind of behaviour, driving a wedge between the blue-eyed and green/brown-eyed children. Green/brown-eyed children started to feel confident and began asserting their dominance over blue-eyed children, who began to withdraw from learning and social behaviour. (Bloom, 2005) The following week (Monday), Elliott reversed the experiment, saying that blue-eyed children are actually the superior ones and green/brown-eyed children were the ones with inferior faults and weaknesses. Elliott found that the blue-eyed children were nowhere near as harsh towards the green/brown-eyed children as they were to them the week prior. She concluded that a large aspect of this result was because the blue-eyed children knew how hurtful it was to be discriminated against, they could empathise with the pain of the green/brown-eyed children and didn’t need to be assertive or make them feel even worse. (Bland, 2018) Although this experiment was designed to teach young students about discrimination, it also highlights the power of empathy and perspective-taking, as understanding the thoughts and feelings of those who’s wellbeing was anything but satisfied led to more altruistic behaviours instead of egoistic ones. |

Applications of the empathy-altruism hypothesis

[edit | edit source]

Where and how is the empathy-altruism hypothesis applied?

[edit | edit source]There is a limited evidence that highlights the practical applications of the EAH, as people are often motivated by different things to reach a goal. It is also difficult to gather when the EAH takes effect in settings outside of experiments such as in a professional workplace, as these actions cannot be recorded (Batson et al., 2015). Instead, one way to find the potential benefits is to examine workplaces which require individuals to have and display empathy-induced altruism. Empathy-induced altruism is a specific type of altruism, as the result of altruistic behaviours derives from feelings of empathy more so than other feelings that lead to altruism such as pride, pity or egoism. Three examples of workplaces that enforce the use of empathy-directed altruism include workers in the healthcare industry, educators and people working in volunteer groups. Although other forms of motivation such as the desire for money, stability and enjoyment are also prevalent, some consistency of empathy-induced altruism is needed to be successful in these roles.

Healthcare workers

[edit | edit source]Communication is one of the most vital skills a healthcare professional needs (Moudatsou et al., 2020). When talking with patients or clients, a health care profession (HCP) must understand their feelings and opinions, before using that to help assess the patient’s or client’s needs. By using empathy-induced altruism, HCPs are able to first assess the wellbeing of their patient or client. Using empathy-related techniques, HCPs can gain insight into the other’s perspective, giving the HCP a better understanding of why they are feeling a particular way (i.e., nervous, angry, upset, etc.) and what they can do to relieve any negative feelings by trying to restore the patient/client’s wellbeing (Moudatsou, 2015).

Although there is an emphasis on empathy in the healthcare industry, some studies have shown a decrease in altruistic motivation in general. Empathy-induced care seems to differentiate between empathy-induced altruism as expressed by Feldman (2017), meaning that although medical staff are likely to be empathetic, decisions involving altruism have no significant effect on helping patients or clients. This is due to increased working hours and burnout, which are common causes for the decline in empathy-induced altruism.

| Reflective question:

Do you find yourself acting altruistically in your workplace or school? Is that altruism a result of self-oriented motivation (you do it because it makes you feel good) or other-oriented motivation (you do it because it makes others feel better). |

Educators

[edit | edit source]Education is a life-long experience, and is a crucial factor in how successful people are, not just in terms of financial success, but success in regards to wellbeing, needs, social success and self-actualisation (Michaela, 2015). Similar to healthcare workers, educators need some form of empathy-induced altruism to better reach out towards others. For example, as Fry and Runyan (2017) mention, teaching empathic concern in classrooms gives students the opportunity to understand its importance, and for them to use it in practical applications and experience the benefits for themselves. This reasoning, should encourage teachers to act as role models and to provide both the knowledge of empathic concern, and to enforce the practicality of empathy-derived altruism. This however, is not always the case.

Olitalia et al. (2013) performed an experiment on teachers in Jakarta to analyse where the altruism derived from, and the emotions and motivations behind altruism by the teachers. Olitalia et al. (2013) found that teachers were more altruistically driven by feelings of egoism and personal distress, rather than from empathic concern. Similar to healthcare workers, this concludes that egoistic-derived altruism appears to be favoured over empathy-derived altruism.

Volunteers

[edit | edit source]Volunteering is one of the most altruistic things a person can do. As a result, it is common for one to think that empathy-derived altruism would be at its peak for individuals heavily or somewhat involved in charity work and other similar prosocial experiences. Studies conducted by Davis et al. (1999) have identified that individuals with higher levels of empathic concern were more likely to perform altruistic behaviours such as volunteer work, which gave them direct experiences with those they were helping.

Similar to roles in teaching and healthcare, volunteer workers can be motivated egoistically just as much as they can be from empathetic concern. Researchers examining the applications of altruism thus turn to using terms that can be achieved through either self-oriented or other-oriented motivations such as helping behaviours or prosocial behaviours (Einolf, 2008). This is designed to find the significance of altruism that derives from either empathic concern, egoism or both. Einolf (2008) further explains that although the applications of empathy-derived altruism can be difficult to conclude since other applications deriving from self-oriented behaviours may be present, there is a significant correlation between the level of empathic concern an individual has, and the amount of volunteering that they perform or would like to perform. This shows that there is some application of the EAH in regards to volunteering.

Practicality of the empathy-altruism hypothesis

[edit | edit source]The EAH also has practical applications in how people deal with obstacles. Similar to where and how the EAH is applied, the best way for examining the practicality is to look at empathy-derived altruism and empathic concern. This is because empathy-derived altruism and empathic concern can be identified as real-world behaviours, which can therefore be tested and better understood.

Empathic concern can be used in everyday life, as well as in professional settings as mentioned before. The best examples stem from social interactions which can be fixed or relieved through empathic concern. Results found by Depow et al. (2021) suggests, as seen in Figure 2, that people find it easier to empathise with positive emotions such as joy and happiness, over negative emotions like sadness or distress. This highlights that empathic concern regarding fixing the wellbeing of others is considerably harder than empathic concern regarding an individual who is already at a positive state of wellbeing. It is important at this point to ask yourself, do you feel that you would empathise more with your co-worker who is having a bad day at work, or with your best friend who landed their dream job? Batson et al. (2015) however, suggests that it is easier to empathise with someone who is currently in a situation that you have experienced already or currently. So, although studies have explored that people may empathise more with their best friend getting their dream job, it is just as likely that individuals may feel motivated to help those that are experiencing similar negative experiences that they have once experienced such as a bad day at work, therefore leading towards an empathy-derived type of altruism.

|

Quiz 1

|

|

Quiz 2

|

Motivation and reward- Why are people motivated to help, what is the benefit?

[edit | edit source]The EAH examines the possibility of empathic concern as the key determinant that leads to altruistic motivation. This hypothesis does not include forms of selfishness or egoism, but instead looks at selfless qualities as the driving force behind altruistic behaviour (Batson et al., 2015). The EAH does not neglect or disprove other key determinants of altruism such as personal distress or social rewards, but instead tries to focus on a single aspect. However, if the ultimate goal of empathy-derived altruism is to help the recipient improve their state of wellbeing, is it enough to drive individuals to making more altruistic acts?

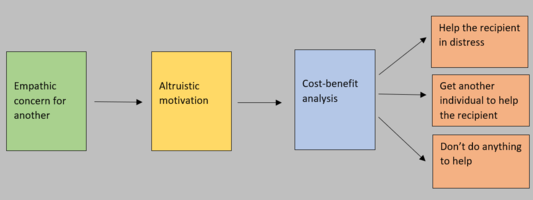

It can feel good

[edit | edit source]In most cases, helping others makes one feel good. It can give the actor a sense of accomplishment and reinforce positive feelings. As Lahvis (2016) mentions, feeling good is a consequence of empathetic-altruism, it is not the goal. Other forms of altruism such as the empathic-joy hypothesis or social-exchange theory states that feeling good can be the ultimate goal of helping another individual (Batson et al., 1991). The EAH also establishes a cost-benefit analysis, as seen in Figure 3, but instead of weighing up the rewards for performing altruistic actions such as the social-exchange theory, the EAH differentiates the best choice between:

- helping the recipient

- getting another individual to help the recipient or

- to do nothing at all (Batson et al., 2015).

Batson et al. (2015) also mention that these choices depend on specific circumstances and other forms of motivation present. Choosing to do nothing or getting another individual to aid the recipient does not imply that the EAH was not in effect, but instead shows that the cost-benefit analysis proved that the worst choice to make for that particular situation is to help, either because the risks of harm were too high, or harm could be brought out in another (Batson et al., 2015). In order for empathy-derived altruism to make one feel good, the cost-benefit analysis should sway towards the first two options, as doing something makes one feel good about improving another’s wellbeing in some way (Batson et al., 2015). There are however, more benefits to empathic-derived altruism besides feeling good.

Other motivating benefits

[edit | edit source]Other benefits that can derive from altruistic behaviours include social and extrinsic rewards. One idea suggests that empathic-altruism might be the initial motivation of helping another, however, an extrinsic reward placed afterwards may shift one’s motivation. A study conducted by Warneken and Tomasello (2014) investigated the altruistic tendencies of infants aged 20 months before and after they received an extrinsic reward. Extrinsic rewards appeared to reduce the likeliness of future altruistic behaviours. Warneken and Tomasello (2014) demonstrated that humans are altruistic by nature, meaning that they are most likely empathy-derived, but prosocial rewards can deeply affect the likeliness of altruistic behaviours, either by reducing the tendency to help, or by changing one’s mindset to help as it benefits oneself with a reward. Additionally, Lahvis (2016) highlights that altruistic efforts might be a result of the camaraderie effect, which incorporates feelings of empathy with social motivation. The camaraderie effect combines parts of the EAH, with the desire to socialise with others as a leading factor for wanting to help the wellbeing of another. To summarise, altruistic behaviours driven from empathy may be the initial reason for helping another’s wellbeing, however, other factors can steer individuals away from altruistic behaviour or adjust their motivations behind it.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The EAH theory attempts to explain if and how people perform altruism purely to improve the wellbeing of another. It is important to understand the foundations of the key words involved in the theory, specifically empathy and altruism. The EAH continues to gain and lose support as more experiments are conducted. This is because there are numerous other forms of motivation and goals that shift the reasoning of performing altruistic actions.

The EAH can be implemented in all workplaces, but the most likely places to find empathy-derived altruism comes from individuals whose jobs require a lot of empathy to succeed, such as healthcare workers, educators and volunteers. While altruistic behaviours may begin from an empathic emotion, other forms of motivation and rewards can change one’s reason for choosing to be altruistic or not. This includes personal distress branching from egoism and extrinsic rewards stemming from social recognition and social motivation.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Altruism (Wikipedia)

- Altruism and empathy (Book chapter, 2014)

- Compassion and empathy (Book chapter, 2014)

- Egoism (Wikipedia)

- Empathic concern (Wikipedia)

- Empathy (Wikipedia)

- Empathy (Book chapter, 2011)

- Empathy and emotional wellbeing (Book chapter, 2015)

- Guilt and empathy (Book chapter, 2018)

- Hypothesis (Wikipedia)

- Social exchange theory (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Batson, C. D. (1987). Prosocial Motivation: Is it ever Truly Altruistic? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 65–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065- 2601(08)60412-8

Batson, C. D., Batson, J. G., Slingsby, J. K., Harrell, K. L., Peekna, H. M., & Todd, R. M. (1991). Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.413

Batson, C. D., Lishner, D. A., & Stocks, E. L. (2015). The Empathy–Altruism Hypothesis. The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior, 1–27.

Batson, C. D., & Moran, T. (1999). Empathy-induced altruism in a prisoner’s dilemma. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(7), 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199911)29:7<909::AID-EJSP965>3.0.CO;2-L

Bloom, S. G. (2005, September 1). Lesson of a Lifetime. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/lesson-of-a-lifetime-72754306/

Bradford, A. (2017a, July 26). What Is a Scientific Hypothesis? | Definition of Hypothesis. Livescience.Com. https://www.livescience.com/21490-what-is-a-scientific-hypothesis-definition-of-hypothesis.html

Bradford, A. (2017b, July 29). What Is a Law in Science? Livescience.Com. https://www.livescience.com/21457-what-is-a-law-in-science-definition-of-scientific-law.html

Burks, D. J., Youll, L. K., & Durtschi, J. P. (2012). The Empathy-Altruism Association and Its Relevance to Health Care Professions. Social Behavior and Personality. An International Journal, 40(3), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.3.395

Cherry, K. (2021, April 14). Why We Risk Our Own Well-Being to Help Others. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-altruism-2794828

Davis, M. H., Mitchell, K. V., Hall, J. A., Lothert, J., Snapp, T., & Meyer, M. (1999). Empathy, expectations, and situational preferences: Personality influences on the decision to participate in volunteer helping behaviors. Journal of Personality, 67(3), 469–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00062

Depow, G. J., Francis, Z., & Inzlicht, M. (2021). The experience of empathy in everyday life. Psychological Science, 32(8), 1198–1213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797621995202

de Waal, F. B. (2008). Putting the Altruism Back into Altruism: The Evolution of Empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093625

Einolf, C. J. (2008). Empathic concern and prosocial behaviors: A test of experimental results using survey data. Social Science Research, 37(4), 1267–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.06.003

Feldman, M. D. (2017). Altruism and medical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(7), 719–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4067-1

Fry, B. N., & Runyan, J. D. (2017). Teaching empathic concern and altruism in the smartphone age. Journal of Moral Education, 47(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2017.1374932

Greater Good. (n.d.). Altruism Definition | What Is Altruism. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/topic/altruism/definition

Jonason, P. K., & Middleton, J. P. (2015). Dark Triad: The “Dark Side” of Human Personality. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 671–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.25051-4

Karina Bland, The Arizona Republic. (2018, May 30). Blue eyes, brown eyes: What Jane Elliott’s famous experiment says about race 50 years on. The Republic | Azcentral.

Klimecki, O. M. (2019). The Role of Empathy and Compassion in Conflict Resolution. Emotion Review, 11(4), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919838609

Lahvis, G. P. (2016). Social Reward and Empathy as Proximal Contributions to Altruism: The Camaraderie Effect. Social Behavior from Rodents to Humans, 30, 127– 157. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2016_449

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Hypothesis. The Merriam-Webster.Com Dictionary. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hypothesis

Michaela, N. (2015). Educational motivation meets Maslow: Self-actualisation as contextual driver. Journal of Student Engagement: Education Matters, 5(1), 18–27. https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=jseem

Moudatsou, M., Stavropoulou, A., Philalithis, A., & Koukouli, S. (2020). The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare, 8(1), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010026

Olitalia, R., Wijaya, E., Almakiyah, K., & Saraswati, L. (2013). Altruism among teachers. The Asian Conference on Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences 2013 Official Conference Proceedings, 302–310. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271520337_Altruism_among_Teacher

Reeve, J. (2018). Understanding Motivation and Emotion (7th ed.) [E-book]. Wiley.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2013, July 21). Biological altruism. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/altruism-biological/

Taylor, K. (2010, June 11). Psychological vs. Biological Altruism. Philosophy Talk. https://www.philosophytalk.org/blog/psychological-vs-biological-altruism

Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2014). Supplemental material for extrinsic rewards undermine altruistic tendencies in 20-Month-Olds. Motivation Science, 1, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/2333-8113.1.s.43.supp

External links

[edit | edit source]- Aggression vs. altruism: crash course psychology (YouTube, 2015)

- Helping and prosocial behaviour (noba project.com, 2021)

- Introduction to social exchange theory in social work (Online MSW Programs.com)

- Jane Elliott's blue eyes brown eyes experiment (YouTube, 2020)

- The power of empathy (Tedx, 2013)

- What is empathy? (YouTube, 2014)