Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Nightmares and emotion

What are the emotional characteristics of nightmares and what are their consequences?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Nightmares, also called bad dreams, are unpleasant dreams than can cause great feelings of distress, anger, anxiety, fear and/or sadness. Nightmares often occur during REM sleep (rapid eye movement sleep) and can last between 3 minutes in the early stages of sleep to roughly 45 minutes further into the night (Spoormaker, Schredl & Bout, 2006). Although nightmares are seemingly harmless, frequent nightmares can cause a range of problems and disruptions to everyday life such as insomnia and anxiety and can also elevate the severity of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Paul, Schredl & Alpers, 2015; Simor, Csóka & Bódizs, 2010). Problems with nightmares are experienced by a sizeable percentage of those who have experienced trauma in their lifetime and approximately 5% to 8% of the general population (Krakow & Zadra, 2006).

As neuroscience is still in the early stages of research and exploration, the understanding of nightmares and treatment of nightmares is limited. An understanding of the emotional characteristics experienced during nightmares, bad dreams and night terrors will contribute to minimising the effects of nightmares and treat different nightmare disorders effectively. Theories of emotion such as The Cannon-Bard Theory also contribute to recognising the signs of a nightmare and controlling one's own emotions to prevent the potential consequences of reoccurring bad dreams.

|

Focus questions:

|

What are nightmares and why do they occur?

[edit | edit source]Nightmares are often unsettling expressions of dreams conveying emotions of fear, sadness, anger and anxiety through disturbing imagery and events (Nielsen & Levin, 2007). Nightmares can occur as a response to the current anxieties or stressors in one's life, a symptom of PTSD, side effects to medication or symptoms of other mental health problems/illnesses. Nightmares are often more frequent in childhood, particularly between the ages of 5 to 10 yers but can also be prominent in adulthood as a response to existing trauma or anxiety (Schredl, Fricke-Oerkermann, Mitschke, Wiater & Lehmkuhl, 2009; Nielsen & Levin, 2007).

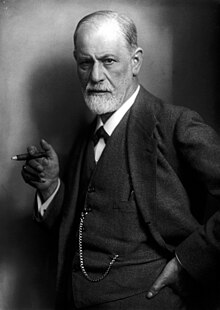

Freud's dream interpretation theory

[edit | edit source]

According to Freud's dream interpretation theory (1900), the content of dreams is derived from our experiences in real life. This includes stimuli from the external world, organic stimuli within the body, subjective experiences and mental activities during sleep. Freud suggested that the connections from our lived experiences and the content of our dreams is not random and is rather a reflection of one's unconscious desires, that dreaming is a form of 'wish fulfillment'. Bad dreams or nightmares, in Freud's theory, are referred to as 'disagreeable' dreams whilst neutral or positive dreams are referred to as 'pleasant' dreams. Freud theorised that dreams can conceal their true purpose as indirect wish fulfillment and as a result, identified two types of dreams; manifest dream and latent dream. Latent dream is considered the real dream with the goal of dream interpretation to reveal it (Zhang & Guo, 2018).

Nightmares in childhood

[edit | edit source]Nightmares are thought to be more common in early childhood due to new stressors and anxieties concerning school, family and social life. These life changes can pose new issues that the child has not previous experienced and therefore can cause great amount of distress that can become present in nightmares (Schredl, Fricke-Oerkermann, Mitschke, Wiater & Lehmkuhl, 2009). In a study investigating the relationship between nightmare frequency and both sleep and waking-life behaviour in children aged between 6 and 11 years, it was found that the occurrence of stressors such as school problems and parental divorce increased the likelihood of frequent nightmares (Schredl et al., 2000). As the child is exposed and adapts to everyday stressors, the frequency of nightmares decreases significantly, often around the age of 10 years (Schredl, Fricke-Oerkermann, Mitschke, Wiater & Lehmkuhl, 2009).

|

Buhler and Largo studied 320 Swiss children from ages 2 to 18 years and found that anxiety dreams were present in 60% of children aged 6 but decreased to 20% at the age of 10 and remains constant until the age of 14 (Schredl et al., 2000). |

Nightmare disorder

[edit | edit source]Nightmares may occur occasionally for the average individual but for those with nightmare disorder, they can occur much more frequently. The emotional characteristics of nightmare disorder are often much more severe than the occasional bad dream causing clinically significant distress that may interfere with day-to-day life. Nightmare disorder may develop due to a catastrophic life event such as the death of a close family member or a mental illness such as PTSD. Nightmare disorder can result in difficulty completing everyday tasks due to anxiety and lack of sleep, impairing social, occupation and other vital aspects of life (Aurora et al., 2010).

Night terrors

[edit | edit source]Night terrors, also called sleep terrors, are not to be confused with nightmares. Night terrors are a sleep disorder that occur in the first hours of REM sleep, lasting approximately between 1 to 10 minutes and cause great feelings of panic or dread (Murray, 1991). A person who experiences night terrors will endure episodes of extreme terror and panic, often taking place during the early phases of sleep and out of a deep sleep. Night terrors occur during sleep stages 3 and 4, dissimilar to nightmares which occur during REM sleep, and exhibit an EEG pattern similar to to waking consciousness. Night terrors are usually more frequent in childhood and can decrease with age, often reducing around the age of 10 years (Murray, 1991). Factors that can influence night terrors consist of lack of sleep, particular medications, stress and fevers (Murray, 1991).

What emotions are associated with nightmares?

[edit | edit source]Emotions are states associated with the nervous system that depict our actions, behaviours, state of mind and reactions to stimuli. The ability to understand and interpret our own and other's emotions is necessary to function in society and interact with others. Emotions can be reflected in countless ways and are particularly intensified during episodes of nightmares and night terrors (Satpute et al., 2016; Tousignant, Glass & Fireman, 2018).

Emotions in nightmares

[edit | edit source]Nightmares are characterised by strong negative feelings, often so prominent they will cause the sleeper to wake as a response to avoid these emotions (Levin & Nielsen, 2009). The emotions that are most commonly expressed during nightmares include fear, dread, anger, sadness, and anxiety. Feelings of grief can also be expressed during nightmares, often in response to the passing of a close friend or family member (Spoormaker, Schredl & Bout, 2006). Unlike night terrors, these emotions are accompanied by vivid imagery, that often triggers these emotions possibly through traumatic or distressing memories or frightening imaginary scenarios (Levin & Nielsen, 2009).

Anxiety and nightmares

[edit | edit source]The content of nightmares is greatly affected by our experiences in waking consciousness, particularly for those who experience regular anxiety (Hasler & Germain, 2009). According to Freud's dream interpretation theory, emotions experienced throughout day-to-day life are often present in our dreams and nightmares and, as a result, the anxieties we experience throughout waking consciousness are also prominent in our dreams (Sikka et al., 2018). In a study to identify the relationship between state of wellbeing and nightmare frequency, 147 participants were asked to report the frequency of their nightmares, log the content of their dreams and rank each dream on a scale of pleasant to unpleasant. Anxiety, depression and neuroticism were found to have strong correlations with nightmare distress (distress experienced in waking-life as a result from frequent nightmares) and frequency of unpleasant dreams (Blagrove et al., 2004). This study not only revealed that anxiety was a key cause of frequent nightmares but was also a reaction to frequent nightmares causing nightmare distress in waking consciousness.

The physiological response to nightmares

[edit | edit source]

Nightmares can also result in physiological responses depending on the severity of the nightmare. Those who experience nightmares can also experience sweating, shortness of breath and periodic leg movements during REM sleep (Gieselmann et al., 2019). The Cannon-Bard theory suggests that the body produces a set of physiological responses to certain emotions. The theory suggests that emotions result when the thalamus sends a message to the brain in response to a stimulus, provoking a physiological reaction. According to this theory, these physical symptoms expressed during nightmares could occur as a reaction to the distressing stimulus present during bad dreams (Dror, 2013).

|

Brain activity during nightmares

In a study to assess whether frequent nightmares relate to a general increase in emotional reactivity or arousal during sleep, the brain activity of 11 healthy sleepers and 11 individuals with nightmare disorder was recorded and observed. In this study, the HEM activity of participants with nightmares was compared to a control group with normal dream activity. The HEM amplitude is increased during high states of emotional arousal and motivation and decreased in periods of depression. It was shown that those who experienced nightmares showed higher HEM amplitude than the control group (Perogamvros et al., 2019). |

Consequences of nightmares

[edit | edit source]Nightmares can cause severe disruptions to everyday life for those living with nightmare disorder or experiencing frequent night terrors. The consequences of nightmares can range from short-term physical symptoms such as sweating or increased heart-rate to the more severe effects such as resurfacing traumatic memories and insomnia (Khazaie, Ghadami & Masoudi, 2016).

PTSD and nightmares

[edit | edit source]Nightmares are often triggered by a traumatic event or experience and the severity of these nightmares can depend on the perceived traumatic magnitude of the experience. For those living with PTSD, frequent nightmares surrounding the trauma can prevent the individual from recovering from the event and can exacerbate the effect of the memory. The individual, although they may be able to control and contain distressing emotions related to their trauma in waking consciousness, may not experience the same sense of control during sleep and as a result, is unable to avoid the resurfacing of painful memories. Nightmares may prolong the recovery process for the individual and may worsen the individual's experience with trauma (Nappi, Drummond & Hall, 2012). In 2006, a study of patients referred to doctors with complains of nightmares, Gupta and Chen found that approximately 32% of patients were living with a form of PTSD (Khazaie, Ghadami & Masoudi, 2016).

|

Case Study - Anne

Anne, 16, is a victim of sexual assault and as a result of the experience has developed post traumatic stress disorder in which she experiences frequent, vivid nightmares that cause her great distress. Anne has undergone treatment purposed to treat her PTSD and panic attacks that she also experiences. Following this treatment, Anne continues to report several nightmares each week. Anne was then provided treatment directly related to addressing the nightmares she experiences through three sessions of cognitive behavioural treatment involving relaxation procedures, exposure to nightmare content and rescripting the nightmare. Following a three-month check up, Anne reported a decrease in the frequency and intensity of her nightmares (Davis et al., 2003). |

Insomnia

[edit | edit source]Particularly for those living with nightmare disorder, insomnia can develop as a means to prevent or minimise the frequency of nightmares. Insomnia is the chronic dissatisfaction with sleep associated with difficulty falling asleep. As a natural response to prevent significantly distressing emotions during sleep, an individual with frequent nightmares may develop difficulties with falling asleep intentionally or unintentionally. An individual with insomnia may also experience frequent awakenings during the night or waking from sleep earlier than desired. The effects and consequences of insomnia are commonly lower mood, irritability, memory loss, fatigue and decrease in energy. Long-term health effects of insomnia include hypertension, diabetes, depression, heart attack, stroke and obesity (Bonnet, 2009).

Treatment of nightmare disorder

[edit | edit source]Due to the lack of current research into the behaviour and causes of nightmares, there are few treatment options that can guarantee recovery. Medications are solely offered to address PTSD associated nightmares and not idiopathic nightmares or drug-induced nightmares. Despite the lack of pharmacological options for treating nightmares, there are a number of behavioural therapies to address the frequency and effects of recurrent nightmares such as:

Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for those with PTSD associated nightmares

[edit | edit source]Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a form of therapy that focuses on distorted throughs, behaviours and emotions through a goal-orientated procedure. CBT is broad term for a number of different methods to address distortions of cognition and behaviour in an individual (Aurora et al., 2010).

In a study assessing 71 patients with PTSD and frequent nightmares as a result of their trauma, 77% of participants reported that they did no longer experience nightmares following CBT. Reported nightmares were reduced after conducting imaginal exposure and continued to decline until the study concluded (Levrier et al., 2016).

Progressive Deep Muscle Relaxation Training for those with idiopathic nightmares

[edit | edit source]Progressive deep muscle relaxation training (PDMR) involves tensing and relaxing the muscles of one part of the body at a time and has shown to relieve stress and anxiety and provide a physical sensation of deep relaxation. PDMR aims to address the emotive causes of nightmares such as anxiety. In a study of 32 female participants with persistent nightmares, PDMR training reduced the frequency of nightmares by 80% in 20-21 participants, 12 of whom reported no longer experiencing issues with nightmares at all. PDMR is a relatively new form of treatment for nightmare disorders and therefore, requires further testing and analysis to demonstrate its effect.

Hypnosis for PTSD associated nightmares

[edit | edit source]Hypnosis or hypnotherapy involves inducing a relaxed and disassociated state of mind in the patient through the use of directive language and a relaxed environment. The patient enters a trance-like state and will experience a feeling of deep relaxation, often calming one's thoughts and emotions. Hypnosis allows the mind to concentrate on specific pieces of information such as memories, thoughts, feelings, emotions, or sensations by temporarily diminishing all feelings of anxiety or concern. For a patient experiencing PTSD, consistent sessions of hypnosis can assist in reducing stress and anxiety and as a result, simultaneously reduce the amount of nightmares the patient may experience in their sleep (Aurora et al., 2010).

In a study involving 10 patients who experienced frequent nightmares, 71% showed signs of improvement or no longer experienced nightmares after 18 months of hypnotherapy. In another study involving three patients with frequent nightmares, between 1 - 5 hypnotic therapy sessions proved to be beneficial for the patients in reducing repetitive nightmares (Aurora et al., 2010).

Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing

[edit | edit source]Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy treats the direct cause of nightmares in patients with PTSD by addressing the patient's experience and associations with trauma (Aurora et al., 2010). The purpose of EMDR in treating nightmares is to enhance information processing and implement new associations between the traumatic memory of the patient and more adaptive memories or information by facilitating the accessing of the traumatic memory network. This procedure involves exposing the patient to 'emotionally disturbing material' whilst also focusing on an external stimulus, most often the eye movement but can also include hand tapping and audio stimulation (Woo, 2014).

Imagery Rehearsal Therapy

[edit | edit source]There are two key components of Image Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) in treating frequent nightmares, both of which target a specific problem within the individual. The first component of IRT addresses 'nightmares as a learned sleep disorder' and the second component addresses 'nightmares as the symptom of a damaged imagery system'. This form of treatment includes four 2-hour sessions equating to approximately 8-9 hours of therapy in total (Krakow & Zadra, 2006).

The first two sessions focus on assisting the patient in recognising the impact of their nightmares by demonstrating how nightmares can cause the patient to develop insomnia. The final two sessions focus on monitoring and managing the connections between daytime imagery and dreams. Although both these components are evident throughout all four sessions, the first two sessions are centred around learned sleep disorders whilst the final two sessions circulate around imagery work (Krakow & Zadra, 2006).

Treatment using IRT has been shown to reduce daytime distress, showing the direct treatment of nightmares can improve quality of life in waking consciousness as well as quality of sleep (Krakow & Zadra, 2006).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Nightmares are unpleasant experiences that can vary in severity and therefore vary in emotional arousal and consequence. These bad dreams are often reflections to the emotions and events that take place in waking consciousness and can cause great stress and anxiety. These nightmares exist as a response to high levels of stress or trauma and are experienced by a large percentage of the population. Although there are a large number of emotional characteristics of nightmares, all characteristics cause great distress in the sleeper, leading to a number of physiological and psychological consequences. The effects of bad dreams are dependent on the severity of the nightmare itself and can often exacerbate the experience of PTSD as well as prolong the recovery process for a trauma victim. Despite this, there are a number of treatment options to address a number of different causes of frequent nightmares. As a newly investigated area of psychology, the cause, characteristics, consequences and treatments for nightmares and nightmare disorder is an ongoing area of research, leaving many questions unanswered.

See also

[edit | edit source]Coping and emotion (Book chapter, 2020)

Emotion regulation and ageing (Book chapter, 2020)

Sleep paralysis (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Blagrove, M., Farmer, L., & Williams, E. (2004). The relationship of nightmare frequency and nightmare distress to well-being. Journal Of Sleep Research, 13(2), 129-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00394.x

Bonnet, M. (2009). Evidence for the Pathophysiology of Insomnia. Sleep, 32(4), 441-442. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/32.4.441

Davis, J., De Arellano, M., Falsetti, S., & Resnick, H. (2003). Treatment of Nightmares Related to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Rape Victim. Clinical Case Studies, 2(4), 283-294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650103256289

Dror, O. (2013). The Cannon–Bard thalamic theory of emotions: A brief genealogy and reappraisal. Emotion Review, 6(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913494898

Gieselmann, A., Ait Aoudia, M., Carr, M., Germain, A., Gorzka, R., & Holzinger, B. et al. (2019). Aetiology and treatment of nightmare disorder: State of the art and future perspectives. Journal Of Sleep Research, 28(4), e12820. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12820

Hasler, B., & Germain, A. (2009). Correlates and Treatments of Nightmares in Adults. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 4(4), 507-517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.07.012

Khazaie, H., Ghadami, M., & Masoudi, M. (2016). Sleep disturbances in veterans with chronic war-induced PTSD. Journal Of Injury And Violence Research, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v8i2.808

Krakow, B., & Zadra, A. (2006). Clinical Management of Chronic Nightmares: Imagery Rehearsal Therapy. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 4(1), 45-70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0401_4

Levin, R., & Nielsen, T. (2009). Nightmares, Bad Dreams, and Emotion Dysregulation. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 18(2), 84-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01614.x

Levrier, K., Marchand, A., Belleville, G., Dominic, B., & Guay, S. (2016). Nightmare Frequency, Nightmare Distress and the Efficiency of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Archives Of Trauma Research, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.5812/atr.33051

Murray, J. (1991). Psychophysiological aspects of nightmares, night Terrors, and sleepwalking. The Journal Of General Psychology, 118(2), 113-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1991.9711137

Nappi, C., Drummond, S., & Hall, J. (2012). Treating nightmares and insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of current evidence. Neuropharmacology, 62(2), 576-585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.029

Nielsen, T., & Levin, R. (2007). Nightmares: A new neurocognitive model. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11(4), 295-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.004

Paul, F., Schredl, M., & Alpers, G. (2015). Nightmares affect the experience of sleep quality but not sleep architecture: an ambulatory polysomnographic study. Borderline Personality Disorder And Emotion Dysregulation, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-014-0023-4

Perogamvros, L., Park, H., Bayer, L., Perrault, A., Blanke, O., & Schwartz, S. (2019). Increased heartbeat-evoked potential during REM sleep in nightmare disorder. Neuroimage: Clinical, 22, 101701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101701

Satpute, A., Nook, E., Narayanan, S., Shu, J., Weber, J., & Ochsner, K. (2016). Emotions in “black and white” or shades of gray? how we think about emotion shapes our perception and neural representation of emotion. Psychological Science, 27(11), 1428-1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616661555

Schredl, M., Fricke-Oerkermann, L., Mitschke, A., Wiater, A., & Lehmkuhl, G. (2009). Longitudinal study of nightmares in children: stability and effect of emotional symptoms. Child Psychiatry And Human Development, 40(3), 439-449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-009-0136-y

Schredl, M., Blomeyer, D., & Görlinger, M. (2000). Nightmares in children: Influencing factors. Somnologie - Schlafforschung Und Schlafmedizin, 4(3), 145-149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-000-0007-z

Sheaves, B., Holmes, E., Rek, S., Taylor, K., Nickless, A., & Waite, F. et al. (2019). Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Nightmares for Patients with Persecutory Delusions (Nites): An Assessor-Blind, Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. The Canadian Journal Of Psychiatry, 070674371984742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719847422

Sikka, P., Pesonen, H., & Revonsuo, A. (2018). Peace of mind and anxiety in the waking state are related to the affective content of dreams. Scientific Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30721-1

Simor, P., Csóka, S., & Bódizs, R. (2010). Nightmares and bad dreams in patients with borderline personality disorder: fantasy as a coping skill?. The European Journal Of Psychiatry, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.4321/s0213-61632010000100004

Spoormaker, V., Schredl, M., & Bout, J. (2006). Nightmares: from anxiety symptom to sleep disorder. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10(1), 19-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2005.06.001

Tousignant, O., Glass, D., & Fireman, G. (2018). 0936 Emotion regulation function of bad dreams and nightmares. Sleep, 41(suppl_1), 347. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy061.935

Woo, M. (2014). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Treatment of Nightmares: A Case Report. Journal Of EMDR Practice And Research, 8(3), 129-134. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.8.3.129

Zhang, W., & Guo, B. (2018). Freud's Dream Interpretation: A Different Perspective Based on the Self-Organization Theory of Dreaming. Frontiers In Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01553

External links

[edit | edit source]Nightmares and the brain (Harvard Medical School)

Understanding post-traumatic nightmares (University of Melbourne)