Motivation and emotion/Book/2020/Funerals and grief work

How do funerals facilitate grief work?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Grief is a universal emotion. Grief is characterised by pain and a range of physiological and psychological ailments (Averill, 1968). Whilst there are many reasons people grieve, such as a relationship breakdown, this chapter discusses grief as a reaction to the death of a loved one. Grief and mourning differ (Averill, 1968). Grief is a product of evolution, whilst mourning is a cultural expression of grief. Rituals around death, such as funerals, allow for the expression of grief in a culturally acceptable way (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). But do funerals offer long-term benefit to those working through grief? This chapter explores current grief work theories, the purpose of funerals, and how funerals facilitate grief work.

Case study

|

|

Focus questions:

|

Grief and grief work

[edit | edit source]Grief is a process of recognising the reality of a loss (Parkes, & Prigerson, 2010). Grief is the experience of a person who has suffered a loss, including thoughts, feelings, behaviours and physiological changes (Worden, 2018).

What is grief work?

[edit | edit source]

Normal grief and abnormal grief differ (Worden, 2018). Normal grief describes the thoughts, feelings, and physical and behavioural changes which are common after loss (Worden, 2018). Abnormal grief, also called pathological grief or complicated bereavement, does not progress through mourning to completion (Worden, 2019). It is characterised by being overwhelmed and resorting to maladaptive behaviour (Worden, 2018). Grief work involves progressing through mourning to completion, so that abnormal grief can be avoided or overcome.

The process of grief work differs by culture and background of the bereaved person (Nwoye, 2005).

History of grief work

[edit | edit source]Many of the concepts about grief work were proposed by Sigmund Freud (see Figure 1; Stroebe et al., 2005). Freud (1917) distinguished between two grief processes, mourning and melancholia. Mourning is a natural process that takes place in the conscious mind. Melancholia is a pathological process which takes place in the unconscious mind. Freud’s melancholia is associated with pathological grief which is generally regarded as the failure to complete grief work (Stroebe & Stroebe, 1991).

Components of grief work

[edit | edit source]There are many definitions and theories related to grief work. Stroebe and Stroebe (1991) describe grief work as generally involving:

- Cognitively confronting the reality of the loss

- Emphasising memories of the deceased

- Talking about the person’s death and events leading up to the death

- Working towards detachment from the deceased

|

Worden (2018) describes four ‘tasks of mourning’, which are:

|

Parkes and Prigerson (2010) detail four states of mourning which outline the pattern that grieving people will move through. They emphasise that these states overlap and blend into one another, and that they differ widely from person to person and across cultures. They describe the four states as:

|

;Dual process model of grief

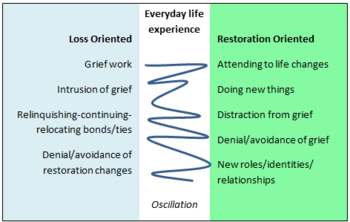

Stroebe and Schut (2010) proposed a dual process model for how people process grief in relation to bereavement (see Figure 2). The model differentiates between two different processes, loss-orientation and restoration orientation. Loss-orientation involves the traditional elements of grief work, such as confronting the reality of loss, going through the events before the death, focusing on memories and working towards detaching from the deceased. Restoration orientation focuses on the need to continue to live life after the loss. A bereaved person moves between these two orientations as they process their grief. |

Look back

[edit | edit source]

Funerals

[edit | edit source]In modern Western society, funerals are generally ceremonies organised by the family of the deceased and a funeral director (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019).

Purpose of a funeral

[edit | edit source]Funerals allow for the expression of loss-related emotions in a culturally acceptable way, and emphasises the person’s transition to death (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). Funerals have four main functions (O’Rourke et al., 2011):

- Maintaining social order

- Supporting religious and spiritual beliefs

- Assisting in the processing of grief

- Allow for the expression of love and respect for the deceased

Funerals across cultures and religions

[edit | edit source]Almost every culture on earth observes death with some kind of ritual, although what these rituals look like changes greatly depending on culture and religion (Hoy, 2013; Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). This section provides some examples of burial rituals in different cultures and religions.

Aboriginal Australian’s "sorry business"

[edit | edit source]"Sorry business" is a term used by Aboriginal Australian’s to describe different rituals associated with death (Carlson & Frazer, 2015). Rituals performed by Aboriginal Australians are diverse and can include ceremonies which last days, performances, and western-style funerals. (Carlson & Frazer, 2015). Across all Aboriginal Australian communities there is a need to participate in funeral rituals, and in some communities participation is mandated by law (Carlson & Frazer, 2015). Sorry business overrides almost all other responsibilities (Carlson & Frazer, 2015).

Buddhist funerals in Tibet

[edit | edit source]Buddhist rituals after death in Tibet are complicated. They focus on ensuring the spiritual well-being of the deceased and preparing the deceased for rebirth (Gouin, 2010). For Tibetan Buddhists, death does not occur once external breathing ceases, rather the body cannot be disturbed until internal breathing has ceased – usually three to four days (Gouin, 2010). There are multiple ways bodies are disposed of in Tibet, including burial, immersion, cremation and exposure which correspond with the elements of earth, water, fire and air (See Figure 3; Gouin, 2010). Each of these methods have their own rituals including prayer, washing the body, and placement of the body (Gouin, 2010).

Cameroon death celebrations

[edit | edit source]Death celebrations link the living and the dead for the people of the Anglophone Northwest Province of Cameroon (Jindra, 2011). They can be held months or even years after the person’s death (Jindra, 2011). They are a social event with families investing all of their financial resources into days of festivities which can include dance performances, gun firings, and feasting (Jindra, 2011). Death celebrations have evolved into a social event which includes people of all ages and religious backgrounds. Christian rituals are often included (Jindra, 2011).

Look back

[edit | edit source]

Funerals and grief work

[edit | edit source]Funerals are a fundamental process in mourning practices (Burrell & Selman, 2020). Funerals facilitate the processing of emotions related to death, and help family and friends of the deceased come to terms with the person’s death (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). They allow bereaved individuals to accept social support and an opportunity for them to show their love and respect for the deceased (Burrell & Selman, 2020).

Benefits of funerals for grief work

[edit | edit source]Researchers have identified several benefits of funerals in relation to grief work:

- Highlighting social supports - Funerals facilitate grief work through highlighting available social support for the bereaved (Gamino et al., 2000).

- Finding meaning in death - By allowing religious rituals to be performed, funerals may allow for death to be contextualised within a religious framework. This allows for the bereaved to take solace in concepts such as an afterlife (Gamino et al., 2000).

- Acknowledging death - Funerals may serve an important function in facilitating separation functions – or the acknowledgement that death has occurred and the deceased will not be returning (Gamino et al., 2000).

- Reducing death-related distress - The tendency to positively eulogise the dead is a behaviour which functions to reduce distress and death-related concern felt by individuals after somebody has died (Hayes, 2016).

Limitation of funerals for grief work

[edit | edit source]A common criticism of funerals in relation to grief work is that they occur too soon after the loss to have positive psychological effects (Worden, 2018). Bereaved people experience the strongest grief emotions between three months and two years after their loss, long after funeral rituals usually take place (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). Whilst attendance at a funeral which the subject rated positively had a short-term impact on positive affect, there was no significant relationship with long-term grief reactions (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019).

Many of the current models of grief work view grief as a long-term process rather than a singular emotional event (O’Rourke et al., 2011). As such, although funerals may be an essential part of cultural mourning practices, the evidence that they contribute significantly to grief work is limited (O’Rourke et al., 2011).

Outcomes associated with negative funeral experiences

[edit | edit source]Bereaved people who found funeral services comforting reported significantly lower levels of grief misery compared to those who attended funerals where adverse events occurred (Gamino et al., 2000). Adverse events included problems with the funeral home or minister, financial issues, and family conflicts (Gamino et al., 2000). These results suggest that funerals may have a positive impact on grief, but only when the funeral is seen to be comforting by the bereaved (Gamino et al., 2000).

Funerals and the grief work models

[edit | edit source]Table 1 summarises the function of funerals in four models of grief work.

Table 1.

How funerals fit into four models of grief work

| Model | Where do funerals fit in? |

|---|---|

| Kübler-Ross model | This model is not linear and is not experienced in the same way by all people experiencing grief (Kübler-Ross, 1969 as cited in Corr, 2019), as such there is no one stage that funerals fit into. |

| Worden’s four tasks of mourning | Worden (2018) describes funerals as being an important part of the first task of mourning – accepting the reality of loss in that it helps emphasise the reality of the death that has occurred. |

| Parkes & Progerson’s states of mourning | Parkes & Prigso (2010) highlighted that for many widows the funeral is where the reality of death becomes real. Until that point, many reported feeling "numb". Numbeness is the first state of mourning (Parkes & Prigson, 2010) |

| Dual process model of coping | This model looks at long-term grief processes (Stroebe & Schut, 2010). Individual differences mean that people may be more loss-orientated or restoration oriented (Stroebe & Schut, 2010), and there is no set point at which people attend a funeral. |

Does the type of funeral matter?

[edit | edit source]Birrell et al. (2000) examined whether the type of ceremony or service offered impacted on long-term grief outcomes. They found no major differences in grief outcomes for those who had attended a minimalistic funeral service compared to an elaborate one.

Gamino et al. (2000) suggested that it is not the type of funeral which matters, but the experience of the funeral, with adverse events at funerals being linked to higher levels of grief misery.

Digital funerals

[edit | edit source]Many Western funeral homes offer live-streaming of funeral services (Walter et al., 2012). Interestingly, online funerals can also be held for those whose social relationships are mostly online (Walter et al., 2012). Walter et al. (2012) described an instance of a 13-year-old girl who played an online game as a fighter pilot. Her gamer friends enacted a virtual fly-past as a tribute. There is little academic evidence examining whether digital attendance at funerals has a differing impact on grief or grief work compared to traditional face-to-face attendance, although some qualitative observations have been positive (Burrell & Selman, 2020).

| COVID-19 and funeral restrictions

The Australian Government (and many Governments around the world) have placed restrictions on numbers of mourners at funerals in order to limit opportunities for the spread of infection. In addition, travel restriction across state borders and internationally has impacted people's abilities to attend funerals. Burrell and Selman (2020) highlighted that, in addition to people not being able to attend at all, those attending a funeral are not able to express comfort physically, through hugs and handshakes, do not have the opportunity to see the extent of social support from friends and family and may feel that they are unable to say their farewells. Restrictions can also have an impact on cultural funeral rituals, such as washing the deceased’s body, which is an important in Islam, Judaism, and Sikhism, and which has been banned or severely restricted through COVID-19 restrictions around the world (Burrell & Selman, 2020). Given what we have learnt regarding the importance of funerals for grief work, what are the potential impacts of these restrictions? |

Look back

[edit | edit source]

Assessing the impact of funerals on grief work

[edit | edit source]As funerals or death rituals are universal, and most grieving people attend a funeral service of some kind, it can be difficult to investigate the relationship between funerals and grief work (Hoy, 2013; Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). This section outlines different methodologies in this field of study.

Quantitative vs qualitative data

[edit | edit source]Burrell and Selman's (2020) review of the effect of funeral practices on the mental health and grief of bereaved family and friends found that studies using qualitative data showed more evidence of positive effects of funeral practices than quantitative data. One reason for this is that a quantitative experimental study with manipulated variables would be unethical in this context (Burrell & Selman, 2020). Qualitative studies were able to indicate that funeral practices were beneficial only when the bereaved were able to shape the ritual in a meaningful way, and when the funeral was able to provide social support for the bereaved (Burrell & Selman, 2020).

Evaluation of the funeral service

[edit | edit source]Mitima-Verloop et al. (2019) suggested that the perception and experience of a funeral may impact grief reactions in those attending. Their longitudinal study examined the relationship between evaluations of a funeral service, other post-funeral grief rituals, and bereavement outcomes. Most participants evaluated the funeral positively and believed that the funeral positively contributed to processing their loss (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). Whilst the study found a small positive association between the funeral evaluation and positive affect shortly after the funeral, the evaluation was not significantly associated with long-term grief reactions or general functioning (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). The evaluation of funeral perception was based on a new scale which requires further testing (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019).

Grief adjustment

[edit | edit source]Research has used grief adjustment as an indicator of how funeral practices have impacted grief work (Bolton & Camp, 1987). Bolton and Camp (1987) used an affect-balance scale and an attitude inventory scale as a measure of grief adjustment. Their results did not find a significant relationship between the amount of rituals practiced and overall grief adjustment (Bolton & Camp, 1987). However, all the widows used in the study participated in funeral rituals so no comparison could be made between funeral participation and overall grief adjustment (Bolton & Camp, 1987).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Grief is a universal emotion which is expressed in different ways depending on the bereaved person’s culture (Averill, 1968). Grief work refers to the processes involved in progressing through mourning to completion, so that abnormal grief can be avoided or overcome (Stroebe et al., 2005). There are several models which describe how people move through this grief process, including the Kübler-Ross model, Worden’s four tasks of mourning, Parkes and Prigerson’s states of mourning, and the dual process model of grief (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010; Stroebe & Schut, 2010; Worden, 2018). There is limited research examining how funeral rituals impact on these grief models.

Funeral rituals are one way people express grief (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). Evidence about how funeral practices impact grief is mixed (Burrell & Selman, 2020). Some evidence indicates that funeral rituals can have positive impacts on grief when the rituals are meaningful and when the funeral provides social support to the bereaved (Burrell & Selman, 2020). On the other hand, there is limited quantitative evidence demonstrating a link between funeral attendance and long-term grief outcomes (Mitima-Verloop et al., 2019). Grief work may be negatively impacted when a negative event happens at a funeral (Gamino et al., 2000). Current models of grief work show grief as a process, rather than a single emotional event (O’Rourke et al., 2011).

The COVID-19 pandemic is impacting the way funerals are attended and experienced across the globe (Burrell & Selman, 2020). The long-term effects of these restrictions may have on the bereaved is unknown and warrants more research.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Bereavement and emotion (Book chapter, 2018)

- Death and emotion (Book chapter, 2014)

- Funerals (Wikipedia)

- Grief (Wikipedia)

- Grief and health (Book chapter, 2015)

- Grief: What it is and how to manage it (Book chapter, 2011)

- Mourning (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Birrell, J., Schut, H., Stroebe, M., Anadria, D., Newsom, C., Woodthorpe, K., Rumble, H., Corden, A., & Smith, Y. (2020). Cremation and grief: Are ways of commemorating the dead related to adjustment over time? Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 81(3), 370–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820919253

Bolton, C., & Camp, D. J. (1987). Funeral rituals and the facilitation of grief work. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 17(4), 343-352. https://doi.org/10.2190/VDHT-MFRC-LY7L-EMN7

Burrell, A., & Selman, L. E. (2020). How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives' mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820941296

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2015). “It’s like going to a cemetery and lighting a candle”: Aboriginal Australians, sorry business and social media. AlterNative: an International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 11(3), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011501100301

Corr, C. (2019). The “five stages” in coping with dying and bereavement: strengths, weaknesses and some alternatives. Mortality, 24(4), 405–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2018.1527826

Freud, S. (1917). Trauer und Melancholie [Mourning and melancholia]. Internationale Zeitschrift für ärztliche Psychoanalyse, 4, 288–301.

Gamino, L. A., Easterling, L. W., Stirman, L. S., & Sewell, K. W. (2000). Grief adjustment as influenced by funeral participation and occurrence of adverse funeral events. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 41(2), 79-92. https://doi.org/10.2190/qmv2-3nt5-bkd5-6aav

Gouin, M. (2010). Tibetan rituals of death: Buddhist funerary practices. Routledge.

Hayes, J. (2016). Praising the dead: On the motivational tendency and psychological function of eulogizing the deceased. Motivation and Emotion, 40(3), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9545-y

Hoy, W. G. (2013). Do funerals matter?: The purposes and practices of death rituals in global perspective. Routledge.

Jindra, M. (2011). The rise of “death celebrations” in the Cameroon grassfields. In M. Jindra & J. Noret (Eds.), Funerals in Africa : Explorations of a social phenomenon (pp. 109-129). Berghahn Books.

Mitima-Verloop, H. B., Mooren, T. T., & Boelen, P. A. (2019). Facilitating grief: An exploration of the function of funerals and rituals in relation to grief reactions. Death Studies, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1686090

Nwoye, A. (2005). Memory healing processes and community intervention in grief work in Africa. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 26(3), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1467-8438.2005.tb00662.x

O'Rourke, T., Spitzberg, B. H., & Hannawa, A. F. (2011). The good funeral: Toward an understanding of funeral participation and satisfaction. ‘’Death Studies’’, 35(8), 729-750. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.553309

Parkes, C., & Prigerson, H. (2010). ‘’Bereavement: studies of grief in adult life’’. Routledge.

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 61(4), 273-289. https://doi.org/10.2190/om.61.4.b

Stroebe, W., Schut, H., & Stroebe, M. (2005). Grief work, disclosure and counselling: Do they help the bereaved? Clinical Psychology Review, 25(4), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.004

Stroebe, M., & Stroebe, W. (1991). Does “Grief Work” Work? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 479–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.3.479

Walter, T., Hourizi, R., Moncur, W., & Pitsillides, S. (2012). Does the internet change how we die and mourn? Overview and analysis. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 64(4), 275-302. https://doi.org/10.2190/om.64.4.a

Worden, J. (2018). Grief counseling and grief therapy : a handbook for the mental health practitioner (5th ed.). Springer Publishing Company, LLC.

External links

[edit | edit source]Australia

[edit | edit source]- Grief and loss (Beyond Blue)

- Griefline

Canada

[edit | edit source]New Zealand

[edit | edit source]United Kingdom

[edit | edit source]United States

[edit | edit source]- Coping with grief and loss (HelpGuide)

- Grief and loss (Harvard Medical Center)