Motivation and emotion/Book/2019/Abortion and emotion

What are the emotional effects of abortion?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Induced abortion or termination of pregnancy (TOP) is the deliberate cessation of a pregnancy resulting in embryonic or foetal death via either a surgical procedure (see figure 1) or the use of medication to induce miscarriage (Pedersen, 2008). There are many circumstances in which a woman would not want to continue a pregnancy and may seek an abortion. Some situations include but are not limited to:

- maternal or foetal health conditions

- not wanting/feeling ready for a child

- not having the financial means

- having an insufficient network of support

(Chor, Lyman, Tusken, Patel, & Gilliam, 2016).

When carried out by trained practitioners following correct procedure, abortions are considered very safe procedures (Grimes et al., 2006). However, if the method utilised is unsafe, abortions can be extremely dangerous or even fatal (Grimes et al., 2006). Abortions performed by untrained individuals, using unsafe or unsanitary equipment, are responsible for a concerning 13% of maternal fatalities (Culwell, Vekemans, de Silva, Hurwitz, & Crane, 2010). The majority of these fatalities occur in developing countries, and countries where abortions are not legal (Grimes et al., 2006). Abortion law varies around the world, currently, 40% of the world provides access to abortion without restriction to reason (Culwell et al., 2010). However, in some countries abortion is only legally available if pregnancy is the result of rape, or it poses a significant threat to the health of the woman, and in a small portion of countries abortion is illegal with no exceptions. In such regions, women who have abortions and any individuals who aid them in doing so may face legal punishment (Boland & Katzive, 2008). See abortion law for more information.

|

Case study

Anna, 22, is a university student completing a Bachelor of Commerce in Canberra, Australia. She and her partner of four years Tom, who is also completing a university degree, have just moved into their first apartment. They are also both working full time jobs to support themselves. After noticing her period was over two weeks late, Anna took a pregnancy test which confirmed she was pregnant. After a discussion, Anna and Tom decided that they were not ready to have a baby, however, Tom assured he would support Anna in whatever decision she made. Anna does not come from a religious family, her mother and father were supportive of Anna's decision to have an abortion. As abortion is legal and has limited restrictions in Canberra, Anna was able to book an appointment at a termination clinic with ease. In the week preceding the appointment, Anna was anxious about the procedure as she was worried it may hurt, however, her friends assured her she had nothing to worry about. Her partner Tom took her to the appointment where Anna had a pain free, uncomplicated experience. She expressed to Tom on the way home that "the nurses were incredibly nice and supportive, one even held my hand when I became anxious". In the weeks following, Anna felt little sadness over the experience and her overwhelming feeling was that of relief. In the years following, Anna rarely thought of the experience. |

|

Focus questions

|

Abortion and emotion

[edit | edit source]Termination of pregnancy (TOP) can affect the emotions of the individual seeking one and those involved, both before and after the procedure. However, in contrast to common belief, the emotions experienced in reaction to abortion are not all negative, or intense as may be assumed. In fact, emotional responses to abortion are complex, unpredictable, and dependant on a multitude of personal and external factors (Freeman, Porat, Rojansky, Elami-Suzin, Winograd, & Ben-Meir, 2016).

It is important to consider emotional response to abortion as twofold:

Emotion prior to an abortion

[edit | edit source]Emotions prior to an abortion are somewhat more predictable than those experienced afterwards. It has been shown that women who anticipates having an abortion experience higher levels of distress and a lower sense of overall well-being compared to the population's average (Bradshaw & Slade, 2003). If a woman is planning on having a surgical abortion, she has a greater likelihood of experiencing anxiety in relation to anticipating the procedure than those who opt for a medical abortion. The more that a woman anticipates discomfort, pain, or complications during the experience, the greater the level of anxiety she will feel prior to the procedure. Social support can mediate this anxiety response, if individuals anticipate the presence of support during the procedure, they are less likely to feel anxiety about the experience (Bradshaw & Slade, 2003).

Emotion following an abortion

[edit | edit source]Women who have undergone an abortion may have positive and (or) negative emotional reactions to the experience, these reactions may be experienced in the short term and (or) the long term (Freeman et al., 2016).

Short-term emotional effects

[edit | edit source]There is evidence that some women have an emotional response to abortion in the period of time directly following, and in the one to two years ensuing the experience (Yilmaz et al., 2010). These feelings may be either positive or negative, and the intensity of such emotions will vary greatly between different individuals (Freeman et al., 2016). However, this sentiment is not true for all women who have abortions, as it is not uncommon for women to have little emotional reaction to abortion, even in the short-term (Freeman et al., 2016).

Immediately after an abortion, most women experience a significant decrease in anxiety levels. This phenomenon can be explained by a reduction in the anxiety experienced as a result of anticipating the abortion.

In the month following an abortion, most research finds evidence for a steady decrease in emotional distress. However, as emotional responses are dependent on situational factors, many cases do not follow this linear progression.

(Bradshaw & Slade, 2003)

Long-term emotional effects

[edit | edit source]The evidence for the long-term effects of abortion is mixed and unclear (Yilmaz et al., 2010). The common sentiment is based on assuming if the procedure is experienced without significant trauma, leading to few long term emotional effects of abortion in research (Yilmaz et al., 2010). Most emotional responses to abortion, whether positive or negative, will decrease steadily over the 1-2 years following the experience, or resolve spontaneously (Faure, & Loxton, 2003).

| "You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health. And reproductive health includes contraception and family planning and access to legal, safe abortion." - Hillary Clinton |

Factors that mediate the emotional affects of abortion

[edit | edit source]The ways in which abortion can affect emotions is unpredictable and heavily dependant on the circumstance surrounding the event. Variables that can significantly affect emotional response include:

Choice

[edit | edit source]The extent to which a woman feels as if she is in control of her decision to have an abortion predicts her adaptive psychosocial adjustment. Women who feel as if they were pressured into having an abortion by a partner, family, community, or associate are more likely to experience depressive symptoms in the short and the long term. The more a woman feels in control of her decision to have an abortion, the more likely it is that she will adapt without negative emotional consequences (Broen, Moum, Bödtker & Ekeberg, 2005).

Legality

[edit | edit source]Although abortion is legal with restrictions in many countries, the legal conditions by which it is allowed vary greatly (Boland & Katzive, 2008). Depending on the reasons for which a woman seeks an abortion, there may be specific requirements she must meet, or additional procedures she must go through in order to acquire it (Boland & Katzive, 2008). These conditions vary greatly between regions, however even in countries with the most lax laws regarding abortion, women may still find themselves having to state or prove the reason that they do not wish to continue with pregnancy (Hanschmidt, Linde, Hilbert, Riedel‐ Heller, & Kersting, 2016). By increasing the difficulty in its accessibility and by reducing individual choice on the matter, these restrictions may increase the amount of stress felt by the individual seeking an abortion (Hanschmidt et al., 2016).

Stigma

[edit | edit source]Due to its controversial nature, abortion remains shrouded in stigma (Hanschmidt et al., 2016). This stigma can be considered as the result of many sociocultural factors, including: the legality of abortion, seeing abortion as unethical, and attributing personhood to foetuses, as shown in Figure 2 (Norris, Besset, Steinberg, Kavanaugh, De Zordo, Becker, 2011). Stigma has been shown to have profound detrimental effects on the psychological well-being of those who experience it (Rocca, Kimport, Roberts, Gould, Neuhaus, & Foster, 2015). Experiencing stigma is more likely to have a negative emotional effect on women who have had or are planning on having an abortion (Rocca et al., 2015).

| “I had an abortion. It was the right decision for me and my husband, and it wasn't a difficult decision. Before becoming president of Planned Parenthood… I hadn't really talked about it beyond family and close friends. But I'm here to say, when politicians argue and shout about abortion, they're talking about me — and millions of other women around the country.”

- Cecile Richards, former president of Planned Parenthood (USA)

|

Experience

[edit | edit source]The abortion experience is critical to how positive or negative the emotional consequences are for women. One defining feature of a positive abortion experience is safety. If the abortion experience was one where the woman feels safe and supported, the emotional consequences are far more likely to be positive; in contrast, women who experienced unsafe abortions are far more likely to experience negative emotional outcomes as a result, and this is especially true if the experience was traumatic. If an abortion that is self-performed or performed by an untrained individual results in complications or bodily trauma, the experience is likely to be highly traumatic and trigger significant emotional trauma (Owoo, Lambon-Quayefio & Onuoha, 2019).

Support

[edit | edit source]Receiving support before, during, and following an abortion is one of the most influential factors in predicting how well a woman will cope with the experience of abortion. This support can come from many facets of a woman's life, including friends, family, a romantic partner, abortion clinic workers, or an appointed non-medical support person (doula). Receiving support from just one of these can decrease anxiety preceding an abortion, as well as minimise any negative emotional repercussions following an abortion. Furthermore, having at least one support present whilst undergoing an abortion procedure can help to ensure a more positive experience (Mukkavaara & Lindberg, 2012).

Religion and culture

[edit | edit source]The emotional effects of abortion are highly dependant on the sociocultural context in which they are considered. If a woman experiences an unwanted pregnancy in a culture where abortion heavily conflicts with her religious beliefs, culture, or family, it is highly likely that she will experience greater negative emotional consequences throughout every stage of the abortion process, compared to those who are in a supportive environment. The extent to which a religion or culture accepts or condemns abortion can directly affect how a woman appraises the experience. If a woman has internalised religious or cultural beliefs that denote abortion to be immoral or unethical, it is likely that she will perceive her choice the same way as her beliefs (Major et al., 2009).

Personal characteristics

[edit | edit source]Like many situations that require coping, personal characteristics play a key role in determining how women will respond to having an abortion. As emphasised by the the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, certain personal characteristics such as self-esteem, perceived personal control, and a pessimistic appraisal style can predict such response (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986). For example, a woman with high self-esteem, a strong sense of personal control, and an optimistic appraisal style may be expected to cope well with such the event.

(Major et al., 2009).

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

|

Case study

Julia, 18, is a year 12 student in Melbourne, VIC. Julia comes from a strict Christian background, her family is deeply involved with their local church. Julia recently split up with her boyfriend Dean, whom her parents did not know about. Not long afterwards, Julia found out that she was pregnant. Due to her parents' beliefs on abortion, she did not feel as she was able to confide in her family. After telling her ex-boyfriend, Dean, he was very vocal about his wishes for her to get an abortion. Julia felt pressured and alone. Due to being 18 years of age, Julia was able to book an appointment at a termination clinic for an abortion herself. On the day, Julia went to the appointment alone where she felt rushed by the staff. In the weeks following her abortion, Julia felt saddened by the experience. She often wondered if she had made the right decision. However, after a year had passed, Julia did not feel affected by the experience anymore. She did, however, wished that she had greater support and a more positive experience. |

Psychological theory

[edit | edit source]

There are multiple theories that attempt explain how and why women respond differently to having an abortion. Each theory contributes a distinct, yet important explanation. An interplay between many theories best clarifies this relationship.

Some of these theories include:

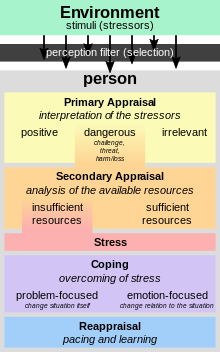

One theoretical model that can help to explain why people differ in their emotional responses to abortion is Lazarus and Folkman's transactional model of stress and coping (Folkman et al., 1986). The model describes response to life events as a result of how they are appraised, or, assessed, by an individual. The theory ascertains that by employing stable internal and external resources such as personality characteristics, social support, and specific aspects of the situation, an individual is able to make cognitive appraisals about situations they encounter. As seen in Figure 3, there are two distinct levels of appraisal that are needed in order to make a full assessment about a situation:

- Primary appraisal: involves an assessment of how a situation will effect the individual. This may include considering the possible benefits / costs etc.

- Secondary appraisal: consideration of the resources an individual has available in order to cope with the situation at hand. This may include social support and personal control.

(Major, Richards, Cooper, Cozzarelli, & Zubek, 1998).

Therefore, in in relation to coping with abortion, this theory ascertains that the the way a woman may respond to having an abortion depends on a multitude of factors, including: how they assess the situation, the extent to which they feel they have the resources to cope, and specific characteristics of the situation such as gestational age, and the age of the woman.

(Major et al., 2009)

Bandura's Self-efficacy theory

[edit | edit source]Self-efficacy refers to the extent to which an individual believes in their capability to achieve desired outcomes as well as coping effectively with aversive events. Albert Bandura determined that, if a person judges themselves to have sufficient internal resources to achieve goals and cope adaptively, they can be labeled as having high self-efficacy (Badura, 1982). This concpet thus mediates how people respond to challenging situations: the greater the sense of internal efficacy someone encompasses, the more adaptively they will cope with negative situations. This proposition can help to explain individual differences in emotional responses to abortion: the extend that a woman believes in her ability to deal with the emotional consequences of abortion directly affects how she will subsequently respond (Major, Cozzarelli, Sciacchitano, Cooper, Testa, & Mueller, 1990).

Aaron Beck's cognitive triad theory determined that an individual's belief system is directly related to their psychological well-being, and in particular, the development of depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, Emery, 1987). As seen in Figure 4, this theory ascertains that people who are prone to depression hold dysfunctional negative thought patterns about the self, the world or the environment, and the future. Beck established that those individuals who see such aspects of life in a negative light will have lower adaptive capabilities in response to negative events. Therefore, women whose thought patterns encompass such characteristics will likely see having an abortion in a more negative light, and subsequently experience more aversive emotional effects.

(Major et al., 1990).

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Abortion has the capacity to bring about both positive and negative emotional consequences for the woman undergoing one, including relief, grief, or even regret. However, the relationship between abortion and its emotional effects is extremely complex and should always be considered in light of context and situation. There is no single, predictable emotional response to having an abortion, as the effects are strongly moderated by factors such as choice, legality, stigma, support, the abortion experience, and the personal characteristics of the woman. Many theories, including Lazarus and Folkman's transactional model of stress and coping, Bandura's Self-efficacy theory, and Beck's Cognitive Triad theory, have attempted to explain this multifaceted relationship. All three theories determined that many of the emotional effects of abortion can be attributed to the way the woman appraises the event, as well as distinct psychological characteristics, such as high self-efficacy and an optimistic/pessimistic attributional style. In summary, the most salient notion discussed within this chapter is that in order for a woman to cope effectively with having an abortion without suffering negative emotional repercussions, it is essential that the following criteria are met: she feels in control of her decision to end the pregnancy, the abortion is both legal and easily accessible, she receives emotional support, and she does not perceive stigma or judgement for her choice.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Abortion (Wikipedia)

- Abortion and emotion (Book chapter, 2018)

- Guilt and motherhood (Book chapter, 2015)

References

[edit | edit source]Beck, Aaron, T.; Rush, A. John; Shaw, Brian F.; Emery, Gary (1987). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-0898629194.

Boland, R., & Katzive, L. (2008). Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007. International Family Planning Perspectives, 34(3), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1363/3411008

Bradshaw, Z., & Slade, P. (2003). The effects of induced abortion on emotional experiences and relationships: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(7), 929–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.001

Broen, A., Moum, T., Bödtker, A., & Ekeberg, Ö. (2005). Reasons for induced abortion and their relation to women’s emotional distress: A prospective, two-year follow-up study. General Hospital Psychiatry, 27(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.09.009

Chor, J., Lyman, P., Tusken, M., Patel, A., & Gilliam, M. (2016). Women’s experiences with doula support during first-trimester surgical abortion: A qualitative study. Contraception, 93(3), 244–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2015.10.006-

Culwell, K., Vekemans, M., de Silva, U., Hurwitz, M., & Crane, B. (2010). Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: Contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 110(Supplement), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.003

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992–1003.

Freeman, M., Porat, N., Rojansky, N., Elami-Suzin, M., Winograd, O., & Ben-Meir, A. (2016). Physical symptoms and emotional responses among women undergoing induced abortion protocols during the second trimester. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 135(2), 154–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.05.008

Grimes, D., Benson, J., Singh, S., Romero, M., Ganatra, B., Okonofua, F., & Shah, I. (2006). Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. The Lancet, 368(9550), 1908–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6

Hanschmidt, F., Linde, K., Hilbert, A., Riedel‐ Heller, S., & Kersting, A. (2016). Abortion stigma: A systematic review. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 48(4), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1363/48e8516

Kero, A., Högberg, U., & Lalos, A. (2004). Wellbeing and mental growth—long-term effects of legal abortion. Social Science & Medicine, 58(12), 2559–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.004

Major, B., Appelbaum, M., Beckman, L., Dutton, M., Russo, N., West, C., & Major, B. (2009). Abortion and mental health: Evaluating the evidence. The American Psychologist, 64(9), 863–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017497

Major, B., Cozzarelli, C., Sciacchitano, A., Cooper, M., Testa, M., & Mueller, P. (1990). Perceived social support, self-efficacy, and adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(3), 452–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.452

Major, B., Richards, C., Cooper, M., Cozzarelli, C., & Zubek, J. (1998). Personal resilience, cognitive appraisals, and coping: An integrative model of adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 735–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.735

Mukkavaara, I., Öhrling, K., & Lindberg, I. (2012). Women’s experiences after an induced second trimester abortion. Midwifery, 28(5), e720–e725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2011.07.011

Norris, A., Besset, D., Steinberg, J.R., Kavanaugh, M.L., De Zordo, S., Becker, D. (2011) Abortion stigma: A reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women’s Health Issues, 21(3), 49-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.010

Owoo, N., Lambon-Quayefio, M., & Onuoha, N. (2019). Abortion experience and self-efficacy: Exploring socioeconomic profiles of GHANAIAN women. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0775-9

Rocca, C., Kimport, K., Roberts, S., Gould, H., Neuhaus, J., & Foster, D. (2015). Decision rightness and emotional responses to abortion in the united states: A longitudinal study(Clinical report). PLoS ONE, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128832

Yilmaz, N., Kanat-Pektas, M., Kilic, S., & Gulerman, C. (2010). Medical or surgical abortion and psychiatric outcomes. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 23(6), 541–544. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767050903191301

External links

[edit | edit source]- Australian abortion laws and statistics

- Abortion isn't on any woman's bucket list (TEDx Talk - Youtube)