Motivation and emotion/Book/2018/Vicarious post-traumatic growth

What is VPTG and what are the key determinants?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Description

[edit | edit source]

What is PTSD?

[edit | edit source]A common psychological disorder around the world today is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This type of stress arises through the exposure to traumatic events that evoke fear, helplessness or horror to an individual. Individual’s diagnosed with PTSD show three main clusters of symptoms. “The first is the persistence re-experience of the traumatic events, such as recurrent dreams and flashbacks. The second is persistent avoidance of internal, or external cues associated with the trauma, such as avoiding thoughts, avoiding activities, diminishes interest, detachment, restricted affect and sense of foreshorten future. Finally, increased arousal is manifested in difficulty sleeping, irritability, difficulty in concentrating, hypervigilance and exaggerated startle response” ("DSM-5", 2018). What people may not be aware of is the disorders ability to not only influence the individual’s psychological health but their physiological health. Evidence has highlighted the long-term physical health issues patients’ experience. “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder may be associated with physical inactivity, a modifiable lifestyle factor that contributes to risk of cardiovascular and other chronic disease” (Winning, 2017). Through this we are able to see the holistic approach that must be taken when treating and caring for someone suffering from PTSG.

What is PTG?

[edit | edit source]Unlike Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) can be seen as the positive outcome from a traumatic situation. “Defined by being the phenomenon of positive change through experience of trauma and adversity”. “Research suggests that the type of trauma sustained could have differing processes and outcomes from each other” (Hefferon, Grealy & Mutrie, 2009). A research done by Kate Hefferon, involved a systematic review of the qualitative literature surrounding the relationship between the individual and their Post-Traumatic Growth. The idea supported that individuals recovering and thriving from illness can create a new awareness and heightened importance of the body. Illness-related survivors reported a new awareness and heightened importance of the body; monitoring one’s health; listening to their own body; improved health behaviours (diet, exercise, reducing stress); routine health checks; vicarious health behaviours; cessation of risky behaviours (drug, alcohol, tobacco, and unprotected sex); and a new positive identification with their own body” (Hefferon, Grealy & Mutrie, 2009). This supports the idea that PTG can have a positive influence of the individual’s outlook on life and themselves.

What is the relationship between PTSD and PTG?

[edit | edit source]The relationship between post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress has shown to be a controversial topic, with several researchers showing opposing sides and data to the relationship. In one of the studies surrounding this topic it has been shown that post-traumatic stress is mutually incompatible with post-traumatic growth. “That is the more stress one experiences in the wake of traumatic event, the less one grows from it, and vice versa” (Updegraff, Taylor, Kemeny & Wyatt, 2002). “Other studies have shown positive correlations, where persons with high levels of distress are most likely to show high psychological growth” (Dekel & Nuttman-Shwartz, 2009). “However, there are also studies that have revealed a curvilinear relationship between exposure to traumatic events and post-traumatic growth, as well as studies that show no relationship the two” (Butler et al., 2005) and (Ai, Tice, Whitsett, Ishisaka & Chim, 2007).

What is Vicarious Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder?

[edit | edit source]What individual’s aren’t aware of is the impact viewing or even hearing about a traumatic event has on the individual. Unlike PTSD, Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth is a positive outcome from traumatic experiences. Instead of the event becoming a stressor for the individual, the stress allows them to grow and perceive the world around them through a positive light. “Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth (VPTG) can be defined as being the growth experienced by an individual due to vicarious or indirect exposure to traumatic events. Various studies have been conducted surrounding this topic in the emergency health care sector. Such as paramedics, midwifes, nurses and doctors” (Kang et al., 2018).

Transfering one's Post-Traumatic Stress into Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth has been the centre of several studies surrounding this topic. A study conducted in China, researched the relationship between VPTG and social support and resilience among paramedics. “The study found that social support was found to have a direct effect on VPTG. It was highlighted that social support provided the necessary resources for victims to cope with trauma and negative psychological reactions. The study hypothesized that that ambulance personal with high levels of social support would have closer interpersonal relationships to meet their emotional demands which in turn, would protect personal against negative outcomes and promote VPTG” (Kang et al., 2018). “Resilience was also seen as a predictor to VPTG, with ambulance personnel with high levels of resilience were more likely to regard indirect trauma as a challenge; so they used problem, focused strategies and were adept at finding something positive about their traumatic experiences” (Kang et al., 2018).

Cross-Cultural Influence

[edit | edit source]The results of VPTG levels in emergency service workers differs across different cultures and societies in the world. In the study ‘The benefits of indirect exposure to trauma; the relationships among vicarious post traumatic growth, social support, and resilience in ambulance personnel in China’, as referred to above. Highlighted the cross-cultural differences among Chinese and Australian emergency service worker’s levels of VPTG. “The research found that levels of VPTG was higher than ambulance officers in Australia, which is due to socio-cultural influences. This can be explained through China’s collectivist culture, with workers working with more pride and responsibility, which reduces distress and promotes the process of growth” (Kang et al., 2018).

Different workplaces has shown to have an influence on the levels of Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth levels in an individual. A study done in Israel compared the VPTG levels of domestic violence therapist and therapists working at social service departments. “The results from this study indicated that the level of VPTG among the participants in both groups were slightly more than moderate. However it was found that therapists working at social service departments reported significantly higher levels of growth. The study goes on to try and explain this s being the result of the individual’s working as therapist in a social services department are exposed to a diverse range of populations that had experiences other kinds of trauma” (Ben-Porat, 2015).

How Do You Measure Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth?

[edit | edit source]When measuring Post-Traumatic Growth Tedeschi and Calhoun created a self-report scale. “The Post Traumatic Growth Inventory assess the salutary impact of traumatic experiences. The scale includes five sub-scales: relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. The study has been known to have strong internal consistency and construct, convergent, and discriminant validity. The ranges of the five sub-scales include; relating to others (0-35), new possibilities (0-25), personal strength (0-20), spiritual change (0-10), and appreciation of life (0-15)” The Relations between Violence Exposure, Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms, Secondary Traumatisation, Vicarious Post Traumatic Growth and Illness. The higher the scores recorded per client the larger the growth they had experienced.

Another way of measuring an individual’s Post-Traumatic Growth is through a Professional Quality of Life Scale. “The questionnaire comprises of 30 items divided into three discreet scales of secondary traumatisation, burnout and compassion satisfaction” (Zerach & Shalev, 2015). If individuals were seen to have an increase or high score they would be seen has having a high quality of life. When using this form of measurement a longitudinal approach must be taken prior and post traumatic event to ensure the validity of the data.

Theoretical background

[edit | edit source]

Functional descriptive model

[edit | edit source]One of the most prominent comprehensive theories in Post-Traumatic Growth is the Functional Descriptive Model. The theory challenges an individual’s perception on the world, creating dissonance between pre- and post-trauma world views therefore causing significant psychological distress and schematic chaos. It is the drive to resolve such dissonance, and the rebuilding of the assumptive world in a meaningful way, that is perceived growth, leading to changes in an individual’s self-perception, relationships with others, and like philosophy. Factors such as personality structure, social support, and coping style are considered by the Functional Descriptive Model to moderate the emotional distress experienced and a growthful outcome” (Splevins, Cohen, Bowley & Joseph, 2010).

Organismic valuing process theory of growth

[edit | edit source]Another theory that expresses a similar opinion to the Functional Descriptive Model is the Organismic Valuing Process Theory of Growth (OVP). Like the Functional Descriptive Model, OVP drives to resolve the dissonance caused and rebuilding of the assumptive world in a meaningful way. “However, the theory is elicit in describing the meta-theoretical assumptions of the term growth and deliberately uses the word to convey the idea of an intrinsic drive toward actualization that is sparked by trauma. According the theory growth can be defined as ‘the natural endpoint of trauma resolution’ and the process is described as being part of an intrinsic human drive” (Splevins, Cohen, Bowley & Joseph, 2010).

Attachment theory

[edit | edit source]Another important theory which helps individuals understand the theoretical scaffolding of a disorder like this is the attachment theory. “This can be explained through the way in which we relate to our care-giving environment, and the consequent impact on our ability to form and maintain relationships and manage emotions. Insecure attachment has been associated with various difficulties, in particular with interpersonal relationships and affect regulation. Difficulties in these areas are characterized of more complex forms of Post-Traumatic disorder, for example after exposure to related abuse as a child. Understandably, and appropriately, attachment theory has been highly influential in the development of complex PTSD and its management” (Splevins, Cohen, Bowley & Joseph, 2010).

Constructivist self-development theory

[edit | edit source]When looking at the theoretical framework of vicarious trauma, the constructivist self-development theory can be used to help understand the emotions behind the individuals. “The theory suggests that individuals construct their realities through the development of cognitive structures or schemes. When possible, new information is assimilated into existing schemas; however, if the new information is incompatible with existing schemas and cannot be assimilated, the original schemas are challenged. When experiencing trauma and also in vicarious traumas, the original schemas can become invalidated or shattered. In these cases, the schemas must be modified to incorporate the new information into the belief system through the process of accommodation. According to the theory, when an individual experiences vicarious traumatisation, schemas are modified in a negative, and this causes distress and heightened awareness to information that supports the new negatively modified schema” (Cohen & Collens, 2013).

Influence on emotions

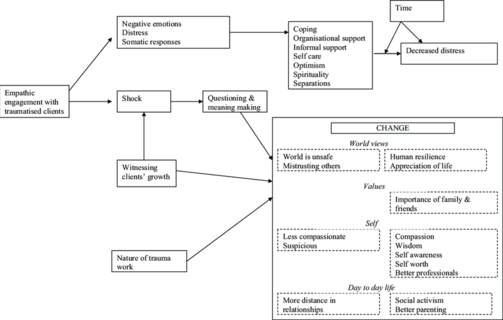

[edit | edit source]A study written by Keren Cohen, ‘The Impact of Trauma Work on Trauma Workers: A Metasynthesis on Vicarious Trauma and Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth’ examines the impact trauma work has on those who are working with traumatised clients. The metasynthesis was done by selecting various articles surrounding the topic. From collaborating the articles together Cohen found four separate themes within the topic.

First theme: emotional and somatic reactions to trauma work

[edit | edit source]The first being the ‘Emotional and Somatic Reactions to Trauma Work’. “When hearing the client’s traumatic story, trauma workers reported an array of emotional responses. These included sadness, anger, fear, frustration, helplessness, powerlessness, despair, and shock. It was seen in some articles that participants also reported somatic responses such as numbness and nausea, tiredness, and even craving sweets. Resulting in some trauma workers having difficulties performing their therapeutic work” (Cohen & Collens, 2013).

Second theme: coping with the emotional impact of trauma work

[edit | edit source]The second theme that was found within the metasynthesis was ‘Coping with the Emotional Impact of Trauma Work’, this highlighted the coping strategies adopted by participates to ensure their health and well-being. “Strategies shown to have a positive influence on the participants include; Managing and mitigating the potential harmful effects of the work, this including managing workload, diversifying workload, one-to-one therapy, providing education and training, proving peer support and supervision and promote opportunities for sharing emotions and debriefing. Self-care behaviours aided participants in the regulation of emotions as well as the promotion of self-care. This included exercising to alleviate stress, healthy eating, resting and mediating, engaging in pleasurable activities. It was also recorded that participants also went to psychotherapy as a strategy to cope with stress and emotions experienced in their work. This enables participants a safe environment to explore their emotions and gain insight into their feelings. Lastly, spirituality was mentioned in several cases as a way of highlighting to participants that their work was meaningful. This enabled them to have an overall positive outlook on life and humour” (Cohen & Collens, 2013).

Third theme: the impact of trauma work–changes to schemas and behavior

[edit | edit source]The research highlighted the impact of trauma work changes has on an individual perception on themselves and the world around them. The third theme found within the metasynthesis highlighted the emotional impact on participants, and how these traumatic experiences triggered a cognitive activity that resulted in changes to the participant’s internal schemas. “In order to make sense if their vicarious experiences, participants reported engaging in an existential meaning-making process, questioning themselves, their lives, and their identities. Several participants viewed the world as unsafe and had a cynical dark view of reality. Throughout the metasynthesis an overall appreciation of life was noticed as well as changes in personal qualities and attitudes, including becoming more compassionate, more accepting toward others, and more humble. There was also reports of having gained wisdom and self-awareness and insight. An increased sense of self-worth, empowerment, and self-validation, was attributes by participants to their trauma work.” Participants described changes to the meanings that they attached to their professional roles and practice, noting that they valued their profession more than before, gained faith and trust in the therapeutic process, and have become better therapist/social workers” (Cohen & Collens, 2013).

Fourth theme: the process of schematic change and relating factors

[edit | edit source]The last theme seen within the study done by Cohen is ‘The Process of Schematic Change and Relating Factors’. “Emotions and time were noted as key factors, moderating the negative emotional impact of the work, with more experience and time leading to less overwhelming emotions and distress. It was also shown that being a witness of one’s growth, the witnessing process facilitated the participant’s own growth” (Cohen & Collens, 2013).

From these themes presented by Cohen we are able to see not only the negative outcomes of a traumatic event but also the positive influences one one’s life. The metasynthesis highlighting the perceptual changes individuals experience when dealing with traumatic or vicarious traumatic events. “Some of the negative psychological emotions reported from the study included sadness, anger, fear, frustration, helplessness, powerlessness, despair and shock. Cohen also highlighted the positive emotions resulting from a traumatic event such as the individual becomes more compassionate, accepting towards others, humble, increased wisdom, self-awareness, insight, self-worth, self-validation and individuals also reported gaining empowerment” (Cohen & Collens, 2013). Cohen’s metasynthesis has been proven to be of great value showing

Quiz

[edit | edit source]Here are three questions to test your understanding! Choose true or false and click "Submit":

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth is not a widely used term used in psychological health. What people aren’t aware of is the positive influence this type of growth can have on an individual perception of themselves and the world around them. Through only metasynthesis are we able to witness the emotional effects this growth has on individuals well-being. From the research conducted by Keren Cohen we are able to see both positive and negative emotions individuals perceive when undergoing VPTG. The positive influences include: individuals becoming more compassionate with individuals surrounding them in their life, accepting of others and more humble. With also increased rates of wisdom, self-awareness, insight, self-worth, self-validation and empowerment. The negative psychological emotions including; sadness, fear, frustration, helplessness, powerlessness, despair and shock” (Cohen & Collens, 2013).

The theoretical framework is strong for this topic. Indicating various reasoning and allowing readers to understand the background of VPTG. The Constructivist Self-Development Theory suggests that individuals construct their realities through the development of cognitive structures or schemas. “According to the theory, when an individual experiences a vicarious traumatisation, schemas are modified in a negative, and this causes distress and heightened awareness to information that supports the new negatively modified schema” (Cohen & Collens, 2013). It is through this theory we are able to identify why individual’s react cognitively differently following a traumatic event. If individuals are seeking guidance for how to transfer their Vicarious Post-Traumatic Stress into Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth this can become a controversial topic, and there is not certain answer that ensures it will happen to an individual. What individuals can do to aid them in creating an opportunity for growth is ensure they have a strong social support” (Kang et al., 2018), “managing one’s workload, diversifying workload, one-to-one therapy, providing education and training, proving peer support and supervision, promote opportunities for sharing emotions and debriefing, self-care behaviours, and creating the workplace an meaningful environment to the employees” (Cohen & Collens, 2013). All being valuable influences on an individual’s ability to change their VPTS into VPTG.

See Also

[edit | edit source]- Vicarious trauma effects on the emotionality of mental health workers (Book chapter, 2016)

- Trauma

- Evidence based assessment/Posttraumatic stress disorder (disorder portfolio)

- Motivation and emotion

- Post-traumatic growth

References

[edit | edit source]Ben-Porat, A. (2015). Vicarious Post-Traumatic Growth: Domestic Violence Therapists Versus Social Service Department Therapists in Israel. Journal Of Family Violence, 30(7), 923-933. https://doi:10.1007/s10896-015-9714-x

Butler, L., Blasey, C., Garlan, R., McCaslin, S., Azarow, J., & Chen, X. et al. (2005). Posttraumatic Growth Following the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001: Cognitive, Coping, and Trauma Symptom Predictors in an Internet Convenience Sample. Traumatology, 11(4), 247-267. https://doi:10.1177/153476560501100405

Cohen, K., & Collens, P. (2013). The impact of trauma work on trauma workers: A metasynthesis on vicarious trauma and vicarious posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, And Policy, 5(6), 570-580. https://doi:10.1037/a0030388

Dekel, R., & Nuttman-Shwartz, O. (2009). Posttraumatic Stress and Growth: The Contribution of Cognitive Appraisal and Sense of Belonging to the Country. Health & Social Work, 34(2), 87-96. https://doi:10.1093/hsw/34.2.87

DSM-5. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

Hefferon, K., Grealy, M., & Mutrie, N. (2009). Post-traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. British Journal Of Health Psychology, 14(2), 343-378. https://doi:10.1348/135910708x332936

Kang, X., Fang, Y., Li, S., Liu, Y., Zhao, D., & Feng, X. et al. (2018). The Benefits of Indirect Exposure to Trauma: The Relationships among Vicarious Posttraumatic Growth, Social Support, and Resilience in Ambulance Personnel in China. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(5), 452-459. https://doi:10.30773/pi.2017.11.08.1

Splevins, K., Cohen, K., Bowley, J., & Joseph, S. (2010). Theories of Posttraumatic Growth: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Journal Of Loss And Trauma, 15(3), 259-277. https://doi:10.1080/15325020903382111

Updegraff, J., Taylor, S., Kemeny, M., & Wyatt, G. (2002). Positive and Negative Effects of HIV Infection in Women with Low Socioeconomic Resources. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 382-394. https://doi:10.1177/0146167202286009

Winning, A., Gilsanz, P., Koenen, K., Roberts, A., Chen, Q., & Sumner, J. et al. (2017). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and 20-Year Physical Activity Trends Among Women. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine, 52(6), 753-760. https://doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.040

External links

[edit | edit source]- Description of link (Systematic literature review)

- Psychguides

- beyondblue.

- theconversation.

- Resources needing clarification

- Resources needing improved grammar

- Resources needing clarification by what

- Resources needing clarification by who

- Motivation and emotion/Book/2018

- Motivation and emotion/Book/Psychological resilience

- Motivation and emotion/Book/Post-traumatic growth

- Motivation and emotion/Book/Vicarious trauma