Motivation and emotion/Book/2018/Guilt

Why do we experience guilt, what are its consequences, and how can it be managed?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Guilt is a cognitive or an emotional experience, where an individual believes they have caused harm to others, compromised their own moral standards, or acted in a socially unacceptable manner. "Guilt is often perceived as a negative experience and after decades of research into emotion, theorists suggest that it is a negative feeling with very positive, social consequences ... Guilt is thought to motivate pro-social behaviours that are aimed at restoring social harmony with the victim, such as confessing, apologising, and attempts to undo the harm or make amends" (De Hooge, 2012., via Izard, 1977). Guilt often arises from a moral wrongdoing where one believes they have done harm to others, primarily by their actions, feelings or thoughts.

|

Focus questions

|

Types of guilt

[edit | edit source]

Guilt is essentially a soicial phenomenon that happens both between people and individually inside them. Guilt appears to arise from interpersonal transactions and vary significantly. Guilt patterns appear to be the strongest, most common and most consistent within the conext of communal relationships (Baumeister et al., 1994).

Various types of guilt include:

- Collective Guilt - Collective guilt otherwise known as group guilt, is the unpleasant and possible emotional reaction that occurs within a group of individuals when they cause harm to others. It is often the result of "sharing a social identity with others whose actions represent a threat to the positivity of that identity."[1]

- Survivor Guilt - Survivor guilt is experienced when a person believes they have done something wrong by surviving a traumatic or life-threatening event when others did not. This form of guilt is most commonly seen in war veterans, those who have lived through natural disasters such as flooding and more.[2]

- Guilt in Mothers - Mother's guilt is seen when something bad happens to the child, for example, a child gets into drugs. The mother starts to blame herself and question where she went wrong and what she could have done better or differently to prevent the circumstances from happening.[3]

- Excessive Guilt - People with bipolar disorder and other depressive disorders, often experience excessive guilt. This is where their conscience blows things out of proportion, causing them to feel disproportionately guilty and remorseful.[4]

- Neurotic Guilt - Neurotic people most commonly suffer from unpleasant feelings of anger, shame, inadequacy, inferiority, covetousness and guilt. Moral guilt means that something wrong has been done and a feeling of guilt is therefore justified. Neurotic guilt is guilt that turns into aggression towards oneself. The overwhelming percentage of guilt that bothers us is neurotic guilt and it is not easy for the sufferer of neurotic guilt to separate the two types of guilt from each other.[5]

Why do we experience guilt?

[edit | edit source]According to Psychology Today common causes of guilt include:

- Guilt for something you did

- Guilt for something you didn't do but want to

- Guilt for something you think you did

- Guilt that you didn't do enough to help someone

- Guilt that you're doing better than someone else

Theories associated with guilt

[edit | edit source]

| Psychological Theory | Main Theorists | Definition |

| Evolutionary Theory | Charles Darwin | Human guilt emerged from natural selection because it prevented human beings from performing exploitative actions that might damage their relationships with others. |

| Behaviourist Theory | Mosher, Bandura | Generalised expectancy for self-mediated punishment (i.e., negative reinforcement) for violating, anticipating the violation of, or failure to attain internalised standards of proper behaviour. |

| Psychodynamic Theory | Sigmund Freud | Moral sense of guilt is the expression of the tension between the ego and the super-ego. |

| Social Learning Theory | Albert Bandura | The notion that people learn their moral senses through observing others actions, behaviours and emotions. |

| Social Psychology | Aristotle, Hegel, Wundt | Group-based emotions are conceptualised as emotions that are experienced because of one's mere association within a group (Rees, Klug & Bamberg, 2014). |

Evolutionary theory

[edit | edit source]According to theorists that look at guilt from an evolutionary perspective, "human guilt emerged from natural selection because it prevented human beings from performing exploitative actions that might damage their relationships with others" (Baumeister, 1994).

Evolutionary game theory

[edit | edit source]"Evolutionary game theory is a branch of mathematics used to model the evolution of strategic behaviour in humans and animals" (Rosenstock & O'Connor, 2018).

The focus for guilt is associated with three classes of behaviours in humans:

- The anticipation of guilt prevents social transgression.

- The experience of guilt leads to a suite of reparative behaviours including apology, gift giving, acceptance of punishment and self-punishment.

- Expressions of guilt lead to decreased punishing behaviours and forgiveness by group members.

Model of guilt apology

[edit | edit source]In the model of guilt apology, "guilt functions by either ensuring trustworthiness of apology, or by leading apologisers to pay a cost. model of guilt apology investigates the evolution of apology by demonstrating how both costly apology and emotion-reading can coincide to stabilise guilt. This approach aims to explore deeper into the conditions in which guilt apology is likely to evolve" (Rosenstock & O'Connor, 2018).

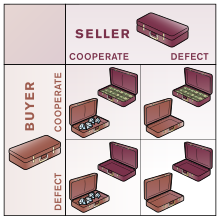

The Prisoner's Dilemma - The prisoner's dilemma is a very common approach within psychology. It is a two-player game where each player has two possible strategies: cooperate or defect. Cooperation in this game is an altruistic strategy, as those that choose to cooperate will incur a cost and increase their partner's payoff. The premise of the game is as follows, if both players cooperate, they both get a moderate payoff, if one cooperates and the other defects, the cooperator gets nothing and the defector gets a large payoff. If they both defect, they both get a small payoff.

The Stag Hunt - "In models that use the "stag hunt" game to represent mutually beneficial, but risky, cooperation, guilt can benefit actors by stabilising such cooperative behaviour. In these types of interactions, it always benefits actors to cooperate when their partners do as well, even in the face of temptation to do otherwise. An emotion, like guilt, that promotes cooperation will then provide individual benefits to any actor in a generally cooperative group. Example, two actors have agreed to hunt a stag together, or cooperate, but one is tempted to hunt a hare instead (to seek short term, less risky, payoff) if anticipation of guilt keeps the actor focused on the stag hunt and their partner pulls through, they will eventually receive greater rewards for sticking to the larger, if riskier, joint project" (Rosenstock & O'Connor, 2018).

Psychodynamic - Interpersonal Theory

[edit | edit source]Freud believed guilt was the product of intrapsychic conflicts stating that guilt was the weapon used by the superego to influence the ego's decisions. In Freud's view, the 'moral sense of guilt is the expression of the tension between the ego and the super-ego, he later insisted that the operation of the superego involved generating feelings of guilt without regard to the outside world' (Baumeister, 1994). According to theories surrounding the notion of self-serving bias, 'many people have a guilty conscience when acting according to an egoistic motive that is in conflict with an otherwise shared social norm' (Otto, P, E., Bolle, F. 2015). Another theorist by the name of Rank (1929), he believed that guilt causes a wish for punishment, he came to understand guilt to be an predetermined side effect of the individuation procedure. According to Rank, guilt originates in the infantile attachment to it's mother and in the fear and anxiety over breaking that attachment, acting as a force that maintains that relationship. De Rivera (1984) agreed with Rank's notion, proposing that all 'emotional states are based on interpersonal relationships and that all emotions are fundamentally concerned with adjusting these relationships' (Baumeister, 1994).

|

"Numerous psychoanalysts believed that many people were dominated by an overly repressive and unforgiving superego, which led to neurotic and harmful guilt. However, Hobart Mowrer argued that the opposite was true; people suffered from anxiety and neurosis because they repressed guilt over real wrongdoing" (Page, 2017). |

What are the consequences associated with guilt?

[edit | edit source]Living with guilt can have many consequences on the individual and those around them. Some of these consequences include:

Guilt as a Protective Factor

[edit | edit source]Often times guilt can be a painful consequence both for an individual and collective groups. As guilt is associated with a painful, negative emotion. Many people who are suffering with feelings of guilt, will do what they can to help minimise those feelings and ensure they do things to make up for their actions. Due to the need/desire to clear ones guilty conscience, this can lead to a positive impact on the environment/situation.

Defenses of Guilt

[edit | edit source]In line with Freud's research, defense mechanisms often adopted from those suffering with guilt are:

- Repression - the psychological attempt to force one's desires and impulses from the consciousness to the unconsciousness as it may be considered socially unacceptable.

- Projection - is when one projects their feelings onto others.

- Victim Blaming - when the victim of a wrongdoing has the blame bestowed upon them.

Guilt and Shame

[edit | edit source]

The emotions of guilt and shame are often used interchangeably, however they differ in their meanings and impacts on an individual. In a psychoanalytic study, Lewis addressed both emotions and concluded 'shame and guilt are ordinarily grouped together because of their common function as drive controls' and that they 'alter the course of instinctual behaviour' (Breggin, 2015).

A series of studies indicate that experiences of guilt and shame are reported widely in individuals with PTSD and that both guilt and shame are closely linked to suicide and suicidal ideation in military samples. Herman with the support of additional theories has proposed that, in some cases PTSD may derive from deep feelings of guilt and/or shame after traumatic events. With this being the case, many within the armed forces are now seeking mental health assistance due to feelings of guilt and shame associated with PTSD-related symptoms. (Nazarov et al).

|

Case Study Example: A study on military mental health and morality suggested that exposure to and perceived perpetration of morally transgressive acts that result in the incurrence of moral injuries during military service are associated with the emergence of symptoms of guilt and shame. The emergence symptoms of guilt and shame following moral injury appears to mediate the onset of psychopathology, including PTSD and MDD, among military members and may increase risk of subsequent suicide (Nazarov et al, 2015). |

How to manage guilt

[edit | edit source]Guilt is an emotionally unpleasant state for an individual to be in, with this being the case, it is fair to say that many would want to escape those emotionally turmoil feelings. People use an array of strategies to help reduce their feelings of guilt.

The basic principles for dealing with guilt according to Psychology Today are the following;

- Addressing the origin of the guilt

- Dealing with the emotion behind the guilt

- Planning a way forward

A significant guilt reduction strategy is to reduce sympathising or empathasing with/for one's victims, this is often done through the process of dehumanising the victim. One regards the victim as an out-group member, with no social ties to the individual, this removes the danger that one's transgression will break social bonds and minimises the basis for empathetic distress. It was found that devaluing one's victim may be a guilt-reduction strategy related to the denial of similar feelings to the victim. Other guilt-reduction strategies focus on the subjective interpretation of the event rather than on the interpersonal relationship. One way to do this is by deconstructing the incident to avoid feelings of guilt, in doing so the individual does not consider the meanings or implications of their actions and therefore are able to escape feelings of guilt (Baumeister, 1994).

|

Example Wegner and Vallacher (1986) suggested that criminals focus their attention to details and procedures rather than on implications, therefore, criminals are able to avoid being disturbed by moral concerns and presumably avoid guilt. A similar suggestion arose from Lifton's (1986) observations of the guards and staff at Nazi concentration camp, it was found that they preferred to avert their attention to checking lists and developing technical procedures instead of focusing on the broader moral implications of the mass murder being carried out (Baumeister, 1994). |

An experimental study by Wertheim & Schwarz (1983) examined the relations between depression, guilt and the choice to delay punishment and gratification with self-management of pleasant and unpleasant events. Many delay-of-gratification studies have followed the paradigm of Mischel in which a subject is given a choice between immediate gratification and a larger but delayed reward. Blatt (1974) suggested that there are at least two forms of depression, helpless depression and guilty depression. Guilty depression tends to arise from introjected anger, it was found that guilt-prone depressives would punish themselves immediately rather than delay punishment. Overall, it was found that depressives who are low in feelings of guilt are more likely to postpone punishment, whereas those displaying high feelings of guilt may seek immediate punishment.

|

Case Study Example In Wertheim & Schwarz's (1983) experiment, it was found that 'proneness to guilt in males related to their preference for immediate punishments. Two interpretations for this were possible. First, disposition to guilt may have had its effect via the mediation of a self-control variable. Research with the Mosher Forced-Choice Guilt Inventory indicates that guilt-prone subjects engage in fewer transgressions of moral standards. Within this study, it was found that the more future-oriented choice of immediate punishment over delayed punishment may have been preferred as the morally correct, self-disciplined choice' (Wertheim & Schwarz, 1983). |

Another guilt management strategy that has been investigated is in the retelling of an event in one's life. When an individual recalls a story, details and information are often altered to highlight the storyteller as either the 'hero' or the 'victim'. An intriguing study done by Akiyo Cantrell (2017) investigated linguistic devices that are often used by such storytellers, such as 'passive voice, evidential markers, honorifics, final particles, direct quotation and special voice qualities. It has been found that storytellers present the self that they want their audience to perceive, typically employing tactics when they bring reported speech into their stories' (Cantrell, 2017). The aim of the study conducted by Cantrell (2017) was to investigate the management of survivors' guilt through the construction of a favourable self in the narratives from survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bombings. The study examined a particular episode that repeatedly occurs: a request for water and its refusal. In order to observe how speakers linguistically construct their stories to display their favourable selves, the study focused on the aspect of survivors stories where the dying victims of the atomic bombing asked for water and the request was rejected by survivors, who had been told that drinking water could result in death. It was found that through the retelling of these stories, the survivors of the attack had started to shift towards feeling of responsibility of survival by refusing water to.

|

Case Study Example A story retold by Mrs Yamada, a survivor of the Hiroshima atomic bombings was free from the responsibility of denying others water, however, she left her friend behind during the attacks. Mrs Yamada's reasoning for leaving her friend are presented strategically within her narrative that her favourable self shines through in the story. Mrs Yamada's favourable self is 'someone who feels sad and guilty about her friend's death, yet strongly holds her commitment to her mother in spite of the incident' (Cantrell, 2017).

|

Test your knowledge

[edit | edit source]Time to test your knowledge - choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Overall, it is evident that guilt is a complex negative emotion which, according to researchers has many positive social consequences such as the desire to rectify one's wrong-doing and cost apology. Guilt is often considered a moral emotion that often acts similar to a moral compass and guides our behaviour to be carried out in a socially acceptable manner. There are many reasons why one may experience feelings of guilt, primarily through doing harm to oneself or others. A significant type of guilt that was investigated throughout this chapter was survivor guilt. Although there are many other factors associated with guilt, the current information chose to focus on survivor guilt.

Although the main psychological theories have defined guilt in some way, the main theories that were attended to throughout was evolutionary theory, particularly the model of guilt apology investigating the effects of the prisoner's dilemma and the stag hunt on feelings of guilt. Another psychological theory that was considered was the psychodynamic theory and the impact of the ego and superego on feelings of guilt and the interpersonal conflicts that may arise from such emotions.

The consequences associated with guilt can be detrimental to an individual's well-being, a guilty conscience can weigh heavily on one's conscience as it is significantly seen in individual's suffering from survivor's guilt. Guilt along with feelings of emotional distress and shame often coincide with the addition of post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder being evident in those in the armed forces returning from duty.

Some guilt management strategies have come into play over the years, many choosing to avoid the feeling all together or focusing on details/procedures to help ignore feelings. Another significant strategy that was noted when studying the life narratives recounted by survivors of the Hiroshima attack is recalling the favourable self. The survivor's would retell the stories to come across as less guilty for their actions so they weren't interpreted as the 'bad guy'.

Overall, guilt is an emotion that can have severe negative impacts on an individual if not dealt with appropriately. Many who have suffered from feelings of guilt, particularly survivor's guilt recall those feelings lasting for many years after the incident. Psychological theories have helped improve one's understanding and knowledge on guilt, however, there is still a long way to go. Studies into the impact of group guilt, where an individual wasn't responsible for the wrong-doing but is affiliated with the group that did the wrong thing. Further studies into this notion could help increase our understanding of associated feeling of guilt and further investigation into mother's guilt would be beneficial when looking into other issues such as postpartum depression.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Guilt and empathy (Book chapter, 2018)

- Guilt and shame (Book chapter, 2018)

References

[edit | edit source]Breggin, P, R. (2015). The biological evolution of guilt, shame and anxiety: A new theory of negative legacy emotions. Medical Hypotheses, 85, 17-24. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2015.03.015f

Brinkman, S. (2010). Guilt in a fluid culture? A view from positioning theory. Culture and Psychology, 16, 253-266. http://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X10361397.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243

Cantrell, A, M. (2017). The management of survivor's guilt through the construction of a favorable self in Hiroshima survivor narratives. Discourse Studies, 19, 377-401. http://doi.org/10.1177/1461445617706589.

Cryder, C. E., Springer, S., & Morewedge, C. K. (2011). Guilty feelings, targeted actions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 607-618. http://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211435796.

De Hooge, I, E. (2012). The exemplary social emotion guilt: Not so relationship-oriented when another person repairs for you. Cognition & Emotion, 26:7, 1189-1207. http://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.640663

Kohut, T. A., & Kellenbach, K. (2014). The mark of cain: Guilt and denial in the post-war lives of Nazi perpetrators. The American Historical Review, 119, 1000-1001. http://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/119.3.1000.

Nazarov, A., Jetly, R., McNeely, H., Kiang, M., Lanius, R., McKinnon, M, C. (2015). Role of morality in the experience of guilt and shame within the armed forces. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 132, 4-19. http://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12406.

Otto, P, E., Bolle, F. (2015). Exploiting one's power with a guilty conscience: An experimental investigation of self-serving biases. Journal of Economic Psychology, 51, 78-89. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.08.005.

Page, C. (2017). Preserving Guilt in the 'Age of Psychology': The curious career of O. Hobart Mowrer. History of Psychology, 20, 1-27. http://doi.org/10.1037/hop0000045.

Parkinson, B. (2010). Relations and dissociations between appraisal and emotion ratings of reasonable and unreasonable anger and guilt. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 347-385. http://doi.org/10.100/026999399379221.

Rees, J, H., Klug, S., Bamberg, S. (2014). Guilt conscience: motivating pro-environmental behavior by inducing negative moral emotions. Climatic Change, 130, 439-452. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1278-x.

Rosenstock, S., O'Connor, C. (2018). When it's good to feel bad: An evolutionary model of guilt and apology. Front. Robot. Al, 5:9, 1-14. http://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2018.00009.

Treeby, M. S., Prado, C., Rice, S. M., Crowe, S. F. (2015). Shame, guilt and facial emotion processing: initial evidence for a positive relationship between guilt-proneness and facial emotion recognition ability. Cognition and Emotion, 30, 1504-1511, http://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1072497.

Wertheim, E, H., Schwarz, C, J. (1983). Depression, guilt, and self-management of pleasant and unpleasant events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 884-889.

Zimmermann, A., Abrams, D., Doosje, B., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2011). Causal and moral responsibility: Antecedents and consequences of group-based guilt. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 825-839. http://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.826.

External links

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Guilt (emotion)". Wikipedia. 2018-08-10. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Guilt_(emotion)&oldid=854273984.

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/fulfillment-any-age/201208/the-definitive-guide-guilt

- ↑ http://cope.org.au/mothers-guilt/

- ↑ https://www.healthline.com/symptom/guilt

- ↑ "How to Overcome Excessive Guilt Feelings - Insight". Insight. 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2018-10-20.