Motivation and emotion/Book/2016/Solastalgia

What is solastalgia and how can we deal with it?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Luke lives in a town called Maitland. Every morning he rides to work; he crosses the bridge over the town’s largest lake where he sees the rays of the rising sun bouncing off the glistening water and the willow trees sprayed along the shoreline with their leaves hanging in the water. After crossing the lake he turns to ride along the main dirt track to his workplace; the lush wildflowers spurting out of the grass on either side of him, their aroma filling the air.

He arrives at work, locks up his bike and quickly pops into the local coffee shop next door where Adam, the shop owner, has his morning coffee and croissant waiting for him. He chats to Adam while sipping his rich flat white - they have become good friends over the years through this morning routine.

Luke heads into work for the day and eight hours later he is back on his bike, waving to Adam as he rides past his shop, and makes it to the lake just in time to see the sun setting over the other side of the lake. The dragon boat team practising on the lake call out to him as he crosses the bridge. They attempt to splash water at him and the cool drops of water refresh him just before he gets home.

Little did Luke know that one day, this would all change. The local government approved a request to build coal mines in and around his city. Within two years, the mines changed the town significantly. Areas of the town were destroyed to accommodate the mines, and the pollution left a haze in the air and an unwelcome odour. The lake soon became intoxicated and Luke’s rides to work were no longer as enjoyable as they were because of the changing environment. The sun no longer glistened in the water as a murky film covered the surface, the willow trees wilted away, and the toxic water was no longer safe for the dragon boat team. The mining trucks used the same dirt track on the other side of the lake as Luke did, and their tyres soon crushed all of the wild flowers.

Adam was forced to sell his coffee shop as his wife had fallen ill from the mining fumes in the air and he needed the money from the sale of the business for her medical bills. Luke’s daily ride was no longer as enjoyable and without his morning coffee he found himself less alert at work. He missed his friend Adam who no longer had time to catch up as he spent most of his time caring for his wife. He began to feel sad - he longed for his previous lifestyle and the great morning that used to get him ready and excited for work. He now dragged his feet behind him as he coughed out the dusty mining air. He soon became unmotivated and the work promotion he had prized now seemed far away. His co-workers weren’t as friendly to him as he had become anti-social. Luke soon fell into a state of depression. Where had his nice life gone? Why was everything changing around him? Why couldn’t Maitland have stayed the same?

What Luke is experiencing in this hypothetical story is solastalgia. Solastalgia is a term used to explain the psychological stress one experiences when grieving the loss of a previous environment, whilst still living in the same place. This is usually due to dramatic environmental change like city development, climate change, invasion, destruction or natural disaster. The term was coined by Glen Albrecht in 2003 and has since gained traction in psychological and environmental discourse. This chapter explores the psychological foundations of solastalgia and considers how to deal with the 'illness' from a psychological perspective.

History and Development

[edit | edit source]Solastalgia is a term coined by Glenn Albrecht in the May of 2003 at the Eco Health Conference in Montreal. Albrecht, an environmental philosopher at The University of Newcastle, Australia, had a growing reputation as an activist for environmental conservation. He often took calls from the public, listening to their concerns on environmental issues. Soon, he began to notice that many of his calls were concerning the Hunter region in New South Wales (NSW) Australia. Many of the callers sought to end the development of open-cut coal mining that had increased in the area, and to control the impact of pollution resulting from the power-stations (Albrecht, 2005, 2010a; Albrecht et al., 2007). Albrecht noted that “their distress about the threats to their identity and well-being, even over the phone, was palpable” (Albrecht, 2005, p41). Inspired by the works of David Rapport, Aldo Leopold and Elyne Mitchell, Albrecht began to take note of the impact environmental change could have on one’s psychological state: “I was confronted by a classic case of the breakdown of this relationship (between land health and human health issues) and it was being clearly manifested in the lives of those people I came into contact with in the Hunter Valley.” (Albrecht, 2005, p42).

Albrecht sought to find a term that would describe the emotion and stress induced by environmental changes in one’s current environment. He contemplated the term ‘nostalgia’ and considered the concept incredibly similar to the state of those living in the Hunter region. Nostalgia, when originally recognised as a psyco-physiological disease, was defined as a feeling of melancholy, stress, and depression caused by grief from absence from one’s home. The word derives from ‘nostos’ meaning ‘return to home or native land’ and ‘algia’ meaning ‘pain or sickness’. Nostalgia is particularly relevant to people who are involuntarily absent from home (e.g., soldiers working in foreign countries) and can cause major depression or even death (Albrecht, 2005, 2010b, 2012).

Over time, the term nostalgia has dropped its original meaning and is now frequently used to describe ‘looking back’ on the past in general and a desire to be back in a previous period of time (Albrecht, 2005, 2010b, 2012). Nostalgia is often used in discussions surrounding misplaced people, invaded people and lost places. However, Albrecht realised that “the places I was interested in were not being completely ‘lost’, they were places being transformed. The people I was concerned about were not being forcibly removed from their homes. However, their place-based distress was connected to powerlessness and a sense that environmental injustice was being perpetrated on them. In the Upper-Hunter, people were suffering from both imposed place transition, and powerlessness” (Albrecht, 2005 , p44).

In order to define the emotional state these people were feeling, Albrecht came up with the term ‘solastalgia’; the first half of the word is derived from the words ‘solace’ and ‘desolation’. Solace is derived from the words ‘solari’ and ‘solacium’, the meanings of which are related to the easing of distress. Desolation has its origins in ‘solus’ and ‘desolare’ with definitions connected to abandonment and loneliness (Albrecht 2005, 2010b, 2012). So, ‘solastalgia’ was born; literally meaning the pain/sickness caused by the loss of solace combined with a sense of isolation connected to the present characteristics of one’s home. In short, it is best explained by Albrecht himself who defined it as:

“an intense desire for the place where one is a resident to be maintained in a state that continues to give comfort or solace. Solastalgia is not about looking back to some golden past, nor is it about seeking another place as ‘home’. It is the ‘lived experience’ of the loss of the present as manifested in a feeling of dislocation; of being undermined by forces that destroy the potential for solace to be derived from the present. In short, solastalgia is a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at ‘home’.” (Albrecht, 2005, p45)

Unpacking the Concept of Solastalgia

[edit | edit source]Solastalgia appears to have affected various types of people undergoing dramatic changes to their environment and therefore their lifestyle. We will now look at some different examples presented in the literature.

Indigenous People

[edit | edit source]Throughout history, both nostalgia and solastalgia have been experienced by indigenous people across the globe (Albrecht 2003; Albrecht et al., 2007; Albrecht & Allison, 2009; Durkalec, Furgal, Skinner, & Sheldon, 2015; Munroe, 2012). Many indigenous people experienced invasion by western powers which claimed their lands and began to develop them without regard for indigenous peoples; resulting in the loss of culture, support and their environment. In Australia, this issue was, and is still particularly evident (Albrecht 2003; Albrecht et al., 2007; Albrecht & Allison, 2009). Indigenous Australians have lived through destruction of their land and culture throughout Australian history since 1788, and the people have experienced a consistent grieving for their loss of culture and country, resulting in physical and mental illnesses at statistically higher rates than other Australians (Albrecht 2003; Albrecht et al., 2007; Albrecht & Allison, 2009).

As a result, Indigenous Australians experience many social problems including substance abuse, unemployment, increased suicide rates, violence (particularly against women) and disproportionately high rates of crime. These issues have led to community dysfunction and crisis, as well as a large stigma attached to indigenous peoples by other Australians (Albrecht 2003; Albrecht et al., 2007; Albrecht & Allison, 2009; Durkalec, Furgal, Skinner, & Sheldon, 2015). Albrecht connects these issues with nostalgia and solastalgia, as Indigenous people mourn the loss of their culture and environment, and the reality that it cannot be recovered. He explained that the various indigenous issues cited above are responses to the solastalgia that they are experiencing (Albrecht 2003; Albrecht et al., 2007; Albrecht & Allison, 2009).

Non-Indigenous People

[edit | edit source]There has been an increase in psychiatric illness in western societies and, as a result, higher counts of suicide and self-harm connected to illnesses such as depression (Albrecht, 2005; McNamara, Westoby, 2011; McManus, Albrecht, & Graham, 2014; Norton, 2011; Sartore, Kelly, Albrecht, & Higginbotham, 2008). Furthermore, the statistics of rural Australians reveal high rates of suicide and depressive illnesses; for example, suicide of male farmers is now approximately double the rate compared to the Australian population (Albrecht, 2005; Eisenman, McCaffrey, Donatello, & Marshal,2015). In Australia, the mental health of farmers is strongly related to the health of the environment. They experience drought, resulting in stock death, malnutrition and thirst, empty dams, and dried up pasture (Albrecht, 2005; Eisenman, McCaffrey, Donatello, & Marshal,2015). It is no surprise that severe depression for farmers soon follows as joy and confidence in their future diminishes. Rural Australia’s high rates of both mental illness and suicide, illustrates a relationship between environmental change and distress and is therefore best explained by solastalgia.

The Upper-Hunter Region NSW

[edit | edit source]Albrecht conducted the first official research into solastalgia using both qualitative and quantitative methods in 2005. The survey participants were from the rural Hunter Region of NSW, including long-term residents as well as recent arrivals from farming and non-farm related occupations. These people had experience dramatic environmental change due to the mining developments in the area (Albrecht, 2005; Albrecht et al., 2007; Higginbotham et al, 2006). Analysis of the data revealed that for a significant number of participants, the environmental change and development the region had experienced was strongly associated with distress about personal health, property damage, landscape damage, and damage to heritage and culture. The study revealed that heightened emotional responses were especially strong when participants responded to the impact of pollution on individuals, family homes and properties, the increased costs of living, the rapid turn-over of community residents, the increasing power of multi-national companies and the increased mistrust between those for and against the developments in the area (Albrecht, 2005; Albrecht et al., 2007; Higginbotham et al, 2006). The incredible loss of ecosystem and community were negatively transforming the foundations of the participants' existence, as their world drastically changed around them. Although the sample in this study was found to be unrepresentative of the population, Albrecht and his colleagues found that survey participants fitted the definition of solastalgia and continued their research in this area (Albrecht, 2005; Albrecht et al., 2007; Higginbotham et al, 2006).

Solastalgia: A new mental illness?

[edit | edit source]Seamus MacSuibhne (2009) discussed this question after discovering the emergence of the term. He explained how Albrecht had labelled solastalgia as ‘a new mental illness’ which many other environmental philosophers supported (MacSuibhne, 2009). However, MacSuibhne explained that none of these environmentalists were psychologists, and pointed out the importance of understanding mental illness as a medical issue with proper diagnostic traits and the need to undertake a number of tests in order for the condition to be put into the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). MacSuibhne(2009) criticised Albrecht for naming his new term as ‘a new mental illness’ as his critics had pointed out the similarities between solastalgia and other mental illnesses in the DSM such as Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, and Adjustment Disorder. Albrecht was quickly criticised as inventing the disease for political reasons, and psychologists argued that it lacked evidence, and was better explained as simply a “problem of living” or simply a struggle people may face in life (MacSuibhne, 2009; Glackin, 2012). MacSuibhne (2009) concludes that people suffering from solastalgia are indeed experiencing distress, but implied that the emergence of a totally new mental illness was not needed. He warned philosophers not to use the term ‘mental illness’ lightly, considering the many implications of the term.

Quiz

[edit | edit source]Here are some quiz questions to test yourself - choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

Solastalgia as a Psychoterratic Illness

[edit | edit source]Albrecht also coined the term ‘psychoterractic illness’ to mean ‘earth-related mental illness’ (Albrecht, et al., 2007; Higginbotham et al 2006, Albrecht, & Graham, 2014). . Arguments for and against solastalgia’s legitimacy as a ‘mental illness’ has been debated. The main argument against it is the timing of the emergence of the illness, corresponding to a time when climate change is hotly debated world-wide, and the fact it was discovered/invented by an environmental activist (MacSuibhne, 2009; Glacklin, 2011). This coincidence seems too strong for some, and those against solastalgia argue that it was simply constructed in order to strengthen the climate change debate and further the movement towards clean energy and ‘greener’ projects (MacSuibhne, 2009; Glacklin, 2011). However, those against solastalgia as a unique mental illness still agree that there are mental health issues correlated to environmental change, but the symptoms are already categorised under other mental illnesses like depression, anxiety, PTSD or adjustment syndrome (MacSuibhne, 2009; Glacklin, 2011.). Furthermore, solastalgia has lacked scientific evidence required to medically classify it as an illness (MacSuibhne, 2009, Glacklin, 2011).

Eisenman, (2015) in his study on rural communities impacted by environmental change due to bushfire, used Higginbotham’s (2006) EDS to find that there was a significant amount of solastalgia distress caused by the natural disasters that had occurred in the region. While Higginbotham (2006), Albrecht (2007) and Eisenman (2015) all critique the EDS’s applicability to the wider populations, they also encourage further research into the realm of solastalgia and call for more experimentation using the EDS to further its reliability/validity. Wood and collegues (2015) looked into solistalgia in their study of staff in a hospital setting analysing their emotions before and after the hospital moved to a new building. Staff mentioned the loss of ‘the sense of community’ and ‘homeliness’ after the move. They also experienced the loss of power and self as they were no longer able to personalise their work spaces. Wood and colleagues (2015) observed how solastalgia was experienced by the staff as they missed their old work environment and longed to salvage the emotional links they had to their old work space. Various studies into ‘place attachment’ have revealed a type of psychological distress like solastalgia in recent years including impacts of natural disaster (Warsini, Mills, & Usher, 2014), climate change in Ghana (Tschaket, Tutu & Alcar0, 2013), drought in rural areas (Sartore, Kelly, Albrecht, & Higginbotham, 2008), and environmental changes due to political violence in Pakistan (Sousa, Kemp, & El-Zuhairi, 2014). Although solastalgia itself is debated as a ‘mental illness’ it is clear the ‘psychoterratic’ or ‘earth-related’ mental illness does occur due to various impacts on one’s environment.

How can we deal with Solastalgia?

[edit | edit source]

Treating the cause

[edit | edit source]Unfortunately literature on solastalgia does not explicitly state how to treat it. As a recently conceived phenomenon, there are mostly case studies and qualitative data which have been difficult to apply to the broader population. Furthermore, most research into the topic has been about its existence rather than about finding a treatment (MacScuibine, 2009). Solastalgia however, does fall under the broader topic of ‘environmental psychology’ which has been researched more extensively. Duralec and colleagues, (2015) discuss the issues arising in Canada where people (particularly indigenous people) experiencing environmental changes have undergone psychological distress and experienced depressive states. Norton (2011) discussed the concept of how humans gain much of their identity from their environment, and so if one’s environment is changed, then emotional issues are likely to follow. Literature has also found that people who are more likely to experience ‘place attachment’ and therefore go through solastalgia-like states are; women, those strongly engaged with their community, people living in rural towns, and farmers. (Albrecht, 2007, Albrecht, McMahon, Bowman, & Bradshaw, 2009; Albrecht & Allison, 2009a, 2009b; Doherty& Clayton, 2011, Lawrence, 2014; Norton, 2011; Sartore, Kelly, Albrecht, & Higginbotham, 2008).

Various solutions have been proposed through the literature to help those suffering from solastalgia, and other ‘place attachment’ based distress. Albrecht (2005, 2010a, 2010b, 2012; 2007) suggests (in particular regard for Indigenous peoples) that community developers, governments and psychologists work on increasing self-empowerment for these communities. Solastalgia has, so far, been attached to environmental change brought in by government, or by natural disaster; so, encouraging the restoration of the sufferer’s ‘home’ can help to bring people back into a place of comfort (Albrecht, 2005; Albrecht & Allison, 2009a, 2009b; Albrecht, McMahon, Bowman, & Bradshaw, 2009; Doherty& Clayton, 2011, Duralec, etal, 2016; Lawrence, 2014; MacScuibine, 2009; Norton, 2011; Sartore, Kelly, Albrecht, & Higginbotham, 2008;). In cases like the Hunter Valley where the changes may be irreversible, the importance of enhancing the remaining aspects of ‘home’ and creating new positive community aspects of solace could help to relieve the destress (Albrecht, 2003; Morrissey & Reser 2007). Clayton and colleagues (2015) noted that much of the literature has focused on ways to minimize harm to the environment in question, but as the world develops and changes there is a growing need to observe how people can best adapt to inevitable changes. They state that this kind of work requires a long-term perspective, engagement with communities, and implementing interdisciplinary skills and ideas. Psychologists can work with designers, planners, decision-makers and policymakers, to enable environmental management and policy change that is properly informed by evidence from research (Clayton et al., 2015). Other suggestions in a similar vein include involving the affected community in the decision making processes. For example, in the Hunter Region, if the governments had given the community more of a say in how the mining and power stations would be established and used, there may have been less of a feeling of ‘powerlessness’. Giving communities the opportunity to be involved in the environmental change process may help to reduce the shock value and further their own empowerment(Albrecht, 2010a, 2012; Anton & Lawrence, 2014; Cole, 2015; Duralec, Furgal, Skinner &Sheldon, 2015; Finegan, 2016) . A major issue in our knowledge of solastalgia is a lack of substantial data and the ‘newness’ of the ‘illness’(Glackin, 2012; Macsuibhne, 2009.) Various authors conclude that more research and more data needs to be collected in order to confirm any treatments or coping strategies (Albrecht, 2012; Glackin, 2012; MacSuibhne, 2011; Norton, 2011; Sousa, Kemp & El-Zuhairi, 2014). Such evidence would enable organisations and governments to better target interventions, enable the development of treatments, and support development of policy that could protect and improve the mental health of communities threatened by, or experiencing, such environmental change.

The Emotion of Solastalgia

[edit | edit source]While the aforementioned strategies can reduce the incidence of Solastalgia, how can we treat the symptoms? The threat of environmental change in one’s habitat is still a critical issue in today’s society due to climate change or natural disasters. Solastalgia is not merely something that can be avoided through strategies, but rather an inescapable issue that may not be avoidable. To discuss how to alleviate the symptoms we will now look at the emotions linked to Solastalgia.

Solastalgia causes feelings of hopelessness, fear, guilt, distress, disgust, despair, grief, anger, sadness and a wide variety of negative emotions (Albrecht 2005, 2007 ; Doherty, Clayton, 2011). Emotion theories summarise these emotions as ‘Negative Emotions’, and these emotions are often a response to threat or harm (Reeve, 2015). Solastalgia is an emotional response to the threat of destruction, or change to, an environment (Albrect, 2003, 2007, 2010a, 2010b, 2012; Albrecht et al., 2007).

Appraisals

[edit | edit source]

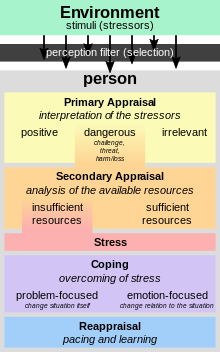

Appraisals are reactions to an evaluation of one’s environment (Reeve, 2014). As solastalgia is an emotional reaction to one’s environment, it is easy to state that these two are correlated. Once an object has been appraised as good or bad, a like or dislike follows which is then followed by positive or negative emotions. In the case of solastalgia, the changes to one’s current environment are appraised as bad, and a dislike of the new situation is developed followed by negative emotions which, when continued for a substantial amount of time and combined with the feelings of powerlessness, then result in the solastalgia. In Lazarus’s complex appraisals a person first assesses whether or not one’s well-being would be altered (Lazarus, 1994; Reeve, 2014) - in the case of solastalgia, people have experienced altered well-being through the destruction or change to their environment. Secondly, the person then assesses whether the effect of the well-being is a benefit, harm, or threat (Lazarus, 1994; Reeve, 2014) - in the case of solastalgia the person has appraised the situation of their environmental state to be of harm or threat. Finally, according to the threats, harms or benefits the person has identified, the emotion then follows (Lazarus, 1994; Reeve, 2014) - in the case of solastalgia they have potentially appraised the harms and threats as the following: • the new environment causes harm to my health – results in fear & anxiety • the new changes to my environment are a result of my lack of action to stop the change from occurring – resulting in guilt • This change is irreversible, I am powerless to change it back – resulting in sadness • I wish it was how it was before, I wish I still had x - resulting in envy of their past self.

Contagion effect

[edit | edit source]The contagion affect refers to the social sharing of emotion. In these social theories of emotion, emotions are explained as a result of mimicking the people around us (Reeve, 2014). For example, if we are around happier people, we are more likely to be happy ourselves. As people share their emotions with us more and more, the likelihood of us experiencing similar emotions (through empathy and subconscious mimicking) is raised. In the case of solastalgia, it is interesting to note that many of the studies are case-studies in rural, close-knit communities (Eisenman, McCaffrey, Donatello, & Marshal, 2015; Higginbotham et al 2006; McManus, Albrecht, & Graham, 2014; McNamara, & Westoby, 2011; Sousa, Kemp & El-Zuhairi, 2014; Tschakert, Tutu, & Alcaro, 2013; Warsini, Mills, & Usher, 2014). As mentioned above, close-knit communities are more likely to experience solastalgia. It could be that the people in this town who have all experienced mild frustration or sadness due to the changes in their environment, have had these emotions elevated as they share them with each other. As people share, the distress spreads further due to the contagion effect.

Self-actualisation

[edit | edit source]

Self-actualisation is a construct many positive psychologists favour (Reeves, 2014). It is based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Reeves, 2015), which places certain aspects of life and survival into a pyramid. As seen in figure 3, the lower levels have basic survival needs like food, shelter, sex, autonomy and so on, and the higher levels have ‘wants’ or desires which are not necessary for survival like riches, looks, power, happiness and so on. According to this model, the highest state one can achieve is reaching self-actualization where a person is content with all they have and are experiencing life to its full potential. In the case of Solastalgia, one might suggest that they are experiencing such distress because their chances of ‘self-actualization’ have been threatened. As one’s comforts and safety are stripped and their hierarchy of needs has been reduced, the person no longer feels safe, secure, healthy or experiencing the things in life that they value due to the changes in the environment. As their environment is no longer providing them with the things they hold dear, they are no longer able to achieve self-actualisation (Reeves, 2014).

Treating The Symptoms

[edit | edit source]These emotions are all encompassed by the loss that one has felt. Grief loss models may be an approach to treating these emotions adequately (Doherty & Clayton, 2009). A contemporary grief loss model by Worden (2009) outlines four main steps to healing; (a) accepting the reality that loss has occurred, (b) processing the physical and emotional pain (c) adjusting to a world without the object; both internally and externally (d) establishing a continuing connection with the object whilst also moving on in a new life without it(Worden, 2009; Doherty & Clayton, 2009). Another technique used to help those experiencing negative emotions that is particularly helpful for those suffering from depression and anxiety is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which Morrissey & Reser (2007) explain could be an effective treatment for those suffering from Solastalgia. As Solastalgia is predominately producing symptoms of anxiety and depression, it makes sense that treating it the same way one would treat anxiety and depression could be an effective solution, particularly as CBT has been found to be effective in a wide variety of socio-economic demographics (Henderson & Mulder, 2016; Morrissey & Reser 2007).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Although solastalgia is debated for its validity in the mental health setting, it is clear that distress caused by change in one’s home environment or ‘homesickness while still home’ is an issue that could be more prevalent in the future. This is due to the fact that climate change, political decisions, the development of communities, war and natural disasters continue to occur all over the world. Solastalgia results in many negative emotions and while emotion theories may be able to help us to understand it more, further study of the concept is required. In the meantime, treating the negative emotions as one would treat emotions related to depression or anxiety is arguably the best form of treatment for severe cases. In addition, it is important to empower communities that are experiencing significant change by giving them a voice in the process, and to implement strategies to retain some of the beloved and 'homely' features of the community. This would encourage more positive outlooks among those who are facing changes in their environments and help to reduce the risk of solastalgia.

See also

[edit | edit source]- [[Motivation and emotion/Book/2015/Climate change and mental health|Climate change and mental health) (Book chapter, 2015)

- Nostalgia and emotion (Book chapter, 2016))

- Emotion (Wikipedia)

- Motivation (Wikipedia)

- Solastalgia (Wikipedia)

- Nostalgia (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Albrecht, G. (2010a). Chronic environmental change: Emerging ‘psychoterratic’syndromes. Climate Change And Well-Being, 43-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9742-5_3

Albrecht, G. (2010b) Solastalgia and the creation of new ways of living. In: Pilgrim, S. and Pretty, J.N., (eds.) Nature and Culture: Rebuilding Lost Connections. Earthscan, London, UK, pp. 207-234.

Albrecht, G. (2012). The age of solastalgia. The Conversation, 7. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/the-age-of-solastalgia-8337

Albrecht, G., Sartore, G., Connor, L., Higginbotham, N., Freeman, S., & Kelly, B. et al. (2007). Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry, 15(s1), S95-S98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10398560701701288

Albrecht, G., McMahon, C.R., Bowman, D.M.J.S. and Bradshaw, C.J.A. (2009) Convergence of culture, ecology, and ethics: Management of feral swamp buffalo in Northern Australia. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 22 (4). pp. 361-378.

Albrecht, G. and Allison, H.E. (2009a) Resilience and water security in two outback towns. In: NCCARF Climate Change Adaptation Symposium, 8 December, Murdoch University, Western Australia.

Albrecht, G. and Allison, H.E. (2009b) Resilient people resilient region. A case study in the Cape to Cape Region of SW Western Australia. In: Sustainable Economic Growth for Regional Australia Conference, SEGRA 2009, 27 - 29 October, Kalgoorlie, Western Australia

Anton, C. & Lawrence, C. (2014). Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal Of Environmental Psychology, 40, 451-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.10.007

Cole, D. (2015). Turning Back Time. Psychology Today, 67-70. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/201505/turning-back-time?collection=1073568

Doherty, T. & Clayton, S. (2011). The psychological impacts of global climate change. American Psychologist, 66(4), 265-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023141

Durkalec, A., Furgal, C., Skinner, M., & Sheldon, T. (2015). Climate change influences on environment as a determinant of Indigenous health: Relationships to place, sea ice, and health in an Inuit community. Social Science & Medicine, 136-137, 17-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.026

Eisenman, D., McCaffrey, S., Donatello, I., & Marshal, G. (2015). An Ecosystems and Vulnerable Populations Perspective on Solastalgia and Psychological Distress After a Wildfire. Ecohealth, 12(4), 602-610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10393-015-1052-1

Finegan, A. (2016). Solastalgia and its cure. Artlink, (36), 28-37. Retrieved from https://www.artlink.com.au/issues/3630/art-land/

Glackin, S. (2012). Kind-Making, objectivity, and political neutrality; the case of Solastalgia. Studies In History And Philosophy Of Science Part C: Studies In History And Philosophy Of Biological And Biomedical Sciences, 43(1), 209-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.11.012

Henderson, S. & Mulder, R. (2015). Climate change and mental disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal Of Psychiatry, 49(11), 1061-1062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0004867415610639

Higginbotham, N., Connor, L., Albrecht, G., Freeman, S., & Agho, K. (2006). Validation of an Environmental Distress Scale. Ecohealth, 3(4), 245-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10393-006-0069-x

Lazarus, R.S.(1994), Universal antecedents of the emotions. In Ekman, P. & Davidson, R. (1994). The nature of emotion. (pp163-171). New York: Oxford University Press.

MacSuibhne, S. (2009). What makes a new "mental illness"?: The cases of solastalgia and hubris syndrome. Cosmos And History: Journal Of Natural And Social Philosophy, 5(2), 210-225.

McManus, P., Albrecht, G., & Graham, R. (2014). Psychoterratic geographies of the Upper Hunter region, Australia. Geoforum, 51, 58-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.09.020

McNamara, K. & Westoby, R. (2011). Solastalgia and the Gendered Nature of Climate Change: An Example from Erub Island, Torres Strait. Ecohealth, 8(2), 233-236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10393-011-0698-6

Morrissey, S. & Reser, J. (2007). Natural disasters, climate change and mental health considerations for rural Australia. Australian Journal Of Rural Health, 15(2), 120-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00865.x

Munro, S. (2012). Rich Land, Wasteland. Google Books. Retrieved 13 October 2016, from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=Q78mf5W2jAEC&pg=PT339&lpg=PT339&dq=dealing+with+solastalgia&source=bl&ots=ARvgVLsV1V&sig=rY4nK8QcWDraiD4PnSUzuJKpODw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj7tLD37-DPAhVhl1QKHVXmAw8Q6AEISjAJ#v=onepage&q=dealing%20with%20solastalgia&f=false

Norton, C. (2011). Social work and the environment: An ecosocial approach. International Journal Of Social Welfare, 21(3), 299-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00853.x

Reeve, J. (2014). Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 6th Edition. John Wiley & Sons.

Sartore, G., Kelly, B., Albrecht, G., & Higginbotham, N. (2008). Control, uncertainty, and expectations for the future: a qualitative study of the impact of drought on a rural Australian community. Rural And Remote Health Research, Education, Practice, And Policy (Internet), 8(950), 1-14. Retrieved from http://www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewnew.asp?ArticleID=950

Sousa, C., Kemp, S., & El-Zuhairi, M. (2014). Dwelling within political violence: Palestinian women’s narratives of home, mental health, and resilience. Health & Place, 30, 205-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.005

Tschakert, P., Tutu, R., & Alcaro, A. (2013). Embodied experiences of environmental and climatic changes in landscapes of everyday life in Ghana. Emotion, Space And Society, 7, 13-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2011.11.001

Warsini, S., Mills, J., & Usher, K. (2014). Solastalgia: Living With the Environmental Damage Caused By Natural Disasters. Prehospital And Disaster Medicine, 29(01), 87-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x13009266

Wood, V., Gesler, W., Curtis, S., Spencer, I., Close, H., Mason, J., & Reilly, J. (2015). ‘Therapeutic landscapes’ and the importance of nostalgia, solastalgia, salvage and abandonment for psychiatric hospital design. Health & Place, 33, 83-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.02.010

Worden, J. W. (2009). Grief counseling and grief therapy (4th ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

External links

[edit | edit source]- The age of solastalgia (Glenn Albrect, 2012)

- "An Interview with Glenn Albrect"

- "Clive Thompson on How the Next Victim of Climate Change Will Be Our Minds" from Wired

- "Creating a language for our psychoterratic emotions and feelings"

- "Jargon Watch: Solastalgia" at Treehugger.com

- "Psychoterratica"

- "Radical Joy for Hard Times"

- "Solastalgia: A new psychoterratic condition" from Healthearth

- "Solastalgia and the Mental Affects of Climate Change"

- "Solastalgia lecture slides by Glenn Albrect"

- "Solastalgia: The Origins and Definition"

- "TEDxSydney - Glenn Albrecht - Environment Change, Distress & Human Emotion Solastalgia"