Motivation and emotion/Book/2016/Narcoterrorism motivation

What motivates narcoterrorism?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Narco-terrorism was a term introduced in 1983 in Latin America by President Fernando Belaunde Terry of Peru. It was used to define violence waged by drug producers on their countries and governments, to further their own political interests. The term itself refers to two types of terrorism; international drug dealers who use radical methods to gain and capitalise on their profits, and terrorist groups who use drug production and trafficking to fund their organisations and operations. Since the term was first introduced, the label ‘narco-terrorism’ has developed various meanings, and different organisations reference different aspects of drug production, dealing and trafficking (Zalman, 2016; “Narcoterrorism”, 2016).

History of Narco-Terrorism

[edit | edit source]

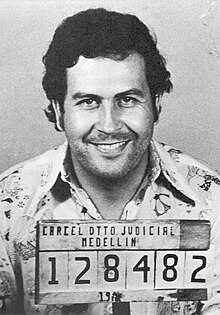

Narco-terrorism became a major concern in the late 1980s during the fight against the Colombian drug cartel and Pablo Escobar, one of the most powerful and violent criminals of all time. During his rise to becoming one of the world’s most notorious drug dealers, Pablo Escobar controlled up to 80% of the cocaine trafficked over to the USA, earning the cartel as much as $420 million a week (“Pablo Escobar Biography”, 2016). Pablo Escobar's rise to power was short-lived when the United States arranged for his capture and extradition. This ultimately led to Escobar’s use of terror tactics on the Colombian government as a way to persuade them into exonerating him. His terrorism attacks resulted in the deaths of thousands of people, including politicians, journalists, judges, police officers and civilians. His attacks took violence to new extremes and included executions, car bombs, and bombing a Colombian jetliner, which killed over 100 people (“Pablo Escobar Biography”, 2016). Escobar's wave of terror attacks used to run his business operations became known as narco-terrorism (Amoruso, 2010). Pablo Escobar's rise to power may have been one of the most influential in making narco-terrorism history, but other criminal groups have acted under similar strategies.

The Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), one of the biggest political armies in the nation, began terrorising the Colombian Government in 1948, after the assassination of leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, of the Liberal Party (“FARC”, 2016). Following the assassination, havoc unfolded; entire villages were attacked for affiliating with the Conservatives. After 15 years of war, almost 20,000 people had lost their lives and hundreds more migrated to nearby cities to escape the conflict (“FARC”, 2016). The group of rebels who fought against the Conservatives slowly began to grow, eventually adopting the name ‘FARC’ in 1966. By the 1970s, the revolutionaries were highly involved in the drug industry, starting their trading through the marijuana market, and later expanding their business to include coca leaf plantations, which funded their organisation for many years to come. Although beginning a peace process with the Colombian Government in 2012, with the rebels agreeing to end all conflict by August 2016, at the peak of their operations in the drug trade, they terrorised many through kidnappings and assassinations, not to mention their debilitating assaults on government forces and police officers (“FARC”, 2016). From the beginning to the end of their battles, the FARC killed up to 220,000 people in the 50-year conflict (Jamal, 2016). Drug trade violence did not stop with the FARC, other organisations from around the globe including the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) who utilized the drug market to fund their movements.

Drug Market

[edit | edit source]The underground drug market has become the most utilised source of funding for many terrorist organisations (Martin, 2012). This is a result of the mammoth earnings the drug trade accumulates, with the United States (US) contributing up to $100 billion annually on illicit substances between 2006 and 2010 (“What America's Users Spend on Illegal Drugs: 2000 –2010”, 2014). The turnover for narcotics globally is estimated at a whopping $400 billion per annum, in cases which were actually reported (“Spending on illegal drugs this year”, 2016). More concerning, worldwide, drug use takes an estimated 95,000 to 226,000 lives annually, with up to 324 million people using illicit substances (“Drug use and its health and social consequences”, 2016).

Drug trade and terrorist organisations

[edit | edit source]Since the deadly attacks in New York and Washington DC on September 11 2001 (9/11), the connection between the drug trade and terrorism has been under the microscope more than ever before. One topic in particular which gained a lot of interest post 9/11, was how terrorism was being funded, with Taliban's involvement in the drug trade becoming more evident (Makarenko, 2004). Afghanistan, the home of al-Qaida and the Taliban, has had the biggest impact on narco-terrorism. It provides 93% of the opium production worldwide. In 2008, opium was sold for an estimated $730 million supplying the Taliban with up to $70 million alone (Haupt, 2009). Alarmingly, terrorist organisations such as the Taliban will continue to be funded as long as substances like heroin are trafficked and sold on our shores (Haupt, 2009).

In Mexico, the cocaine drug war continues to be a worldwide threat, particularly to the US, as its neighbouring cities are frequently exposed to, and forever vulnerable to the conflict generated from the drug trade (Haupt, 2009). Mexico is a base for various terrorist organizations including the FARC and is one of the major producers of the coca plant, which is estimated to provide $39 million in drug proceeds per annum. Mexico provides a direct route from the rest of South America to the US with 90% of their shipments being trafficked over the border into the US (Haupt, 2009). Mexico is known for its lawlessness and corruption, making it the perfect location for various terrorist organisations to congregate with drug cartels, reducing their risk of being caught. In 2009, 19 of 43 formally recognised terrorist groups, were been linked to the drug trade in Mexico by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Of those 19 groups, reports suggested al-Qaeda was in direct contact with FARC, highlighting a number of al-Qaeda‘s operatives spotted at the South American and US borders (Haupt, 2009).

The law

[edit | edit source]

As narco-terrorism involves two types of crime - terrorism and drug offences, the laws surrounding them can be quite complex and are frequently changing. Resultantly, narco-terrorism as a ‘newer’ form of terrorism, has fewer laws applied compared to larger threats like global terrorism.

There are a number of extensive laws in Australia that combat terrorism, national security and cross-jurisdictional offences. According to the Australian National Security Agency, the basis for listing a terrorist group falls under Division 102 of the Criminal Code Act 1995. The code states;

| “ | “For an organisation to be listed as a terrorist organisation, the Attorney-General must be satisfied on reasonable grounds that the organisation is: directly engaged in, preparing, planning, or assisting in fostering the doing of a terrorist act; or advocates the doing of a terrorist act” " |

” |

| — (“Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)”, n.d) | ||

In the Customs Act 1901, a number of drug related offences are also identified including, smuggling illicit substances in and out of the country, manufacturing and cultivation of illicit substances, possession and distribution of substances (“Customs Act 1901”, 1901; “Drug Law in Australia”, 2016).

More specific to narco-terrorism, and as recent as 2006, a narco-terrorism provision was added to the American Patriot Act (Section 112) (Thompson, 2016). The Act states: “Anyone who engages in conduct or conspires in providing, directly, or indirectly, anything of value to any person or organisation terrorist activity… will be sentenced to imprisonment, not less than twice the minimum punishment, and no more than life...” (“One Hundred Ninth Congress of the United States”, 2006).

The current issue

[edit | edit source]| “ | “What we know for a fact is that global drug traffickers and terror networks and insurgent groups often join in a marriage of convenience and do business to raise revenue for their respective purposes,”... “Much of the world’s terror regimes are funded through drug trafficking proceeds, or the taxing of drug routes throughout the world. The threat is real." " |

” |

| — (Payne, as cited in Roy, 2014) | ||

The global drug trade is an ongoing concern in most western countries. Not only does it affect lives around the globe, it is a concern for national security. Terrorism financing not only helps terrorist organisations execute attacks on our shores, it helps establish and maintain terrorist organisations throughout Australia and Overseas, through training, preparing and planning for the next offence. It allows individuals from these organisations to live normal daily lives, and helps provide compensation to families of those who have been killed in terrorist activities (“Tourism Financing in Australia”, 2016). There are a number of ways terrorism financing can occur, these include through self-funding; making an honest living then using the funds to support terrorist groups or one's own terrorist intentions. Furthermore, this can be done through criminal acts such as exploiting charity organizations to raise funds, and transferring large quantities of money to overseas accounts disguised as a donations for aid etc. Funds can also be sent overseas by charities with genuine intentions, to be intercepted by terrorist organisations for their own use (“Tourism Financing in Australia”, 2016). Specific to narco-terrorism, terrorism financing is regularly maintained via the drug trade within Australia and America. Drugs such as opium and cocaine are smuggled into the countries, sold, with the money made smuggled back to the originating countries, funding their terrorist groups. Moreover, as long as the drug market continues to make a profit, and there is demand for illicit drugs, terrorism will be a constant threat around the world (Haupt, 2009).

Problem statement

[edit | edit source]Despite successful counterdrug operations, the drug market is constantly growing. Illicit drugs are a serious threat to the health, safety and financial wellbeing of individuals all around the world (“Transnational Organized Crime”, n.d). More concerningly, the popularity of illicit drugs within the western hemisphere gives terrorist organisations power, allowing them to maintain and hold onto that power fueling further terror related violence. From this, the drug trade is not only detrimental to drug users, through the sales of narcotics, but allows terrorist organisations to further exploit and threaten the western worlds way of life. Futhermore, funding derived from terrorism through the manufacture and sale of narcotics, opens our doors to not only a constant flow of the prohibited substances, but to individuals or organisations with intention to carry out a terrorist act (“Transnational Organized Crime…”, n.d).

Rational Choice Theory

[edit | edit source]

Overview

[edit | edit source]The Rational Choice Theory (RCT) introduced by Cornish and Clarke in 1987, and seeks to identify how criminal behaviour occurs, by analysing the thought processes of an individual. This perspective on crime adopts the idea that criminal offenders commit crimes in order to benefit themselves, and that most criminals are unable to make rational decisions (Cornish & Clarke, 1987). This theory emphasizes that human behaviour is predicted based on the search for pleasure and the avoidance of pain, thus our actions are calculated based on the costs and benefits, and that crime is only committed when there are high chances of rewards and low chances of being caught (Hayward, 2007). The RCT was created to understand criminal decision making in order to potentially prevent future occurrences of crime. In particular, the theory had an emphasis on ‘situational’ crime incidents caused by those who are less functional and have criminal dispositions (Cornish & Clarke, 1987). Crimes being committed on a situational basis are done to benefit the criminal. If the crime at hand does not provide any form of benefit, the criminal will displace their attention elsewhere, until an opportunity arises (Cornish & Clarke, 1987).

How this can be applied to narco-terrorism?

[edit | edit source]The rational choice perspective was introduced in order to understand criminal behaviour, therefore, is applicable to narco-terrorism in a number of ways. For example, in the case of Pablo Escobar, it was evident that he was very much interested in benefiting himself through narcotics production and trade (“Pablo Escobar”, 2015). Though there were always suspicions, in his dealings Escobar was always at arm's reach when it came to committing crimes which he would be directly affiliated with. Those crimes included organising hits on people who had gone against him, like judges in cases against him and liberal party candidates who made threats against him and his trade. He would organise to have them killed, but always made sure that he had no obvious connections to the crime. The RCT does not assume that a person has a predisposition to offend in a particular way; it suggests that the decision to offend is influenced by both the offender and the offence. That the decision to offend is calculated based on an appraisal process, which evaluates the value in the crime, and if it will help achieve the offenders objective (Cornish & Clarke, 1987). In the case of Pablo Escobar, he often had to make assessments regarding what actions were needed to protect him and his business. These assessments led to killing of masses of people, which to him, were all done to benefit himself and his reputation.

Applied example

[edit | edit source]|

On the 18th of August 1989, Luis Carlos Galan, a favoured presidential candidate was assassinated in front of 10,000 people as he was about to step out on stage to deliver a speech at a liberal party convention where he was predicted to be chosen to run for senate (Bedoya, 2014). Galan had no tolerance for drugs or drug organisations, and when elected, had a mission to take on and eradicate Colombia’s drug cartels. This resulted in members of these organisations to viewing him less favourably. Among those was Pablo Escobar who Galan publicly humiliated in front of a crowd of 5000 people during a presidential speech. When there was word that Galan had the votes to win the election, Escobar became uneasy due to the potential implications it would have on him and his cartel. The assassination was a group effort, which included military officers, intelligence directors, the drug cartel, and paramilitaries, who all had apparent connections with Escobar and his cartel (Bedoya, 2014). Eventually, Escobar's hitman ‘Popeye’ was jailed for 22 years for the murder of Galan, after he handed himself into the authorities (Hayward, 2016). Escobar’s everyday dealings showed strong support for RCT as crimes were often committed to benefit him. They were infamously executed in a calculated manner so that he would have higher chance of success while avoiding the punishments of being caught (“Pablo Escobar”, 2015). |

Limitations

[edit | edit source]The RCT provides plausible motivations for crime displacement, and though these motives can be applied to criminal behaviour, there are some limitations to the theory itself. The RCT suggests that it can be applied to all crime situations, that crime in itself is ‘rational’ and always committed to achieve goals (Cornish & Clarke, 1987), but questions have been raised to weather this is the case. Burdon (1998) examined the validity of the theory, questioning if crimes are actually linked to a particular outcome or if they are executed rationally at all. With reference to Pablo Escobar, at his peak it is said that he was involved in up to, if not more than 3000 murders before his death in 1993 (Roper, 2015). According to the RCT, all of the murders were done for a calculated reason. Of those 3000 murders, prostitutes were murdered and so were family members of people who had done him wrong (Roper, 2015). Burdon’s (1998) work queries whether murders like these were premeditated; in Escobar’s case, did they occur because of a ‘legitimate’ reason; or perhaps because he abused his power and got away with it for so long.

Social Movement Theory

[edit | edit source]

Overview

[edit | edit source]The Social Movement Theory (SMT) dates back to the 1960s and is based on the idea of people forming relationships in response to social movements and political opportunities, which more often than not, involve cultural conflict (Metzger, 2016). When culture is involved, a network of people is harmonized and they possess similar qualities and ways of functioning. Networks such these can be extremely hostile to different cultures that have different beliefs and ways of thinking (Metzger, 2016). Much like the Rational Choice Theory, the SMT assumes that those who join a political organisation, do so to maximise their own benefits (Metzger, 2016).

How this can be applied to narco-terrorism?

[edit | edit source]

Al Qaeda and the Taliban are a key example of the SMT in narco-terrorism. These organisations are they heavily involved with the opium market, with most of their funding coming from the sale and trafficking of the illegal narcotics (Haupt, 2009). The organisation is made up of followers who hold similar beliefs and values as one another. Some define these beliefs and values as radical Islam. Although their objectives remain in dispute, Al Qaeda has been known to despise western cultures, more specifically the USA, loathing their way of life and values (Byman, 2003). President Bush stated on September 11, 2001:

"They hate our freedoms: our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote, assemble, and disagree with each other ”… These terrorists kill not merely to end lives, but to disrupt and end a way of life." (Bush, as cited in Byman, 2003).

Followers of al-Qaeda naturally form bonds over their hatred, and with these bonds and such strong beliefs, create a strong terrorist organisation. The actions of al-Qaeda reinforces this theory, as their motives are based on collective objectives, built on common beliefs and motivators, maintained by a group who are hostile toward those who hold different values to their own. These objectives accompanied with their presence in drug market, make them a powerful narco-terrorist organisation.

Applied example

[edit | edit source]|

Al-Qaeda, which was originally founded by Osama bin Laden, dates back to the 1980s when many Arab countries had come together in Afghanistan, to help support the Muslims fight off the attacking Russian Army in the Afghan War. Once the Russians were defeated in 1989, the volunteers formed a faction that is now known as al-Qaeda, who created an alliance against any non-Islamic government ("How did al-Qaeda start?", n.d). Al-Qaeda has had a long hatred of the United States. They maintain the belief that the country is full of infidels, because it is not governed in a way that is consistent with Islam. For this reason, and many others, Bin Laden declared a war on the ‘unbelievers’ of the United States, which has created havoc for century’s ("Background: al-Qaeda", 2014). September 11, 2011 is an example of the extremes the terrorist organisation is willing to go to in the name of their culture and religion. With the millions of dollars of funding allegedly supplied to them from the opium trade, they were able to come together and execute one of the biggest terrorist attacks in America’s history (Haupt, 2009). Terror groups like these show convincing support for the SMT. Such a notorious organisation was established then expanded, based on beliefs and cultures, so strong; they were willing to pledge wars based on them. |

Limitations

[edit | edit source]The SMT has a lot to offer in the study of terrorism and political violence. It provides a great insight what motivates a terrorist organisation, and the strength that culture, and common beliefs create when brought together in a political setting. In the case of al-Qaeda, this means collective threatening movements in the name of religion (Beck, 2008). However, The SMT in regards to terrorism is very limited, and the current literature on the topic is outdated. This is essentially due to the lack of methodology on terrorist organisations, as it would be understandably difficult to gather the information needed direct from the source (Beck, 2008).

Other motivators

[edit | edit source]Other considerations that come to mind when faced with terrorist acts and their consequences are the psychological states of the individual, or individuals, who execute the action. Often people question if the perpetrators are mentally ill, or deranged, to carry out something so sinister (Ruby, 2002). There have been numerous theories established to question exactly that. Of these theories is the Personality Defect Model of Terrorism, which is based on the idea that terrorists have pathological flaws in their personality structures. These shortcomings create hostile individuals who hold negative attitudes of themselves and those around them. These feelings eventually assist them in rationalising terrorist behaviour (Ruby, 2002). In a more learning specific approach, the Social Learning Model of Terrorism suggests, consistent with the theory of aggression, that terrorism is not a result of dysfunctional or flawed personality traits; but the result of learnt experiences and social influences, which the culprits view as completely normal behaviour (Ruby, 2002).

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Theories like the Rational Choice Theory and the Social Movement theory help us understand the motivations behind any form of terrorist behaviour. The Rational Choice Theory was created to understand why criminal behaviour occurs, so there are chances of preventing future incidents (Cornish & Clarke, 1987). In the case of narco-terrorism, theories like these are especially important. In a society where the drug market is continually growing, and terrorist tactics are used on a regular basis to keep the market flourishing, it is an ongoing concern globally. Not only does the drug trade pose a serious threat to the health, safety and financial well-being of people all around the world (“Transnational Organized Crime”, n.d), but it is helping fund terrorist organisations like al-Qaeda, who’s ultimate goal is to destroy our way of living (Byman, 2003). Theories like these are crucial in the fight against narco-terrorism.

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]Amy Zalman, P. (2016). Narcoterrorism. About.com News & Issues. Retrieved from Terrorism About Website: http://terrorism.about.com/od/n/g/Narcoterrorism.htm

Australian National Security. (n.d). Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Retrieved from the Australian Government National Security Website: https://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/Listedterroristorganisations/Pages/KurdistanWorkersPartyPKK.aspx

Beck, C. (2008). The Contribution of Social Movement Theory to Understanding Terrorism. Sociology Compass, 2(5), 1565-1581. doi: org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00148.x

Bedoya, N. (2014). Colombia marks 25th anniversary of Galan’s assassination. Retrieved from the Colombia Reports Website: http://colombiareports.com/luis-carlos-galan-25-years-later/

Biography.com. (2016). Pablo Escobar Biography. Retrieved from the biography Website: http://www.biography.com/people/pablo-escobar-9542497#related-video-gallery

Boudon, R. (1998). Limitations of Rational Choice Theory 1. American Journal of sociology, 104(3), 817-828.

Boudon, R. (1998). Limitations of Rational Choice Theory. American Journal Of Sociology, 104(3), 817-828. doi: org/10.1086/210087

Byman, D. L. (2003). Al-Qaeda as an Adversary do We Understand Our Enemy?. World Politics, 56(01), 139-163.

Collins English Dictionary. (2016). Definition of narco terrorism. Retrieved from the dictionary.com Website: http://www.dictionary.com/browse/narcoterrorism?s=t

Commonwealth Consolidated Acts. (1901). Customs Act 1901. Retrieved from the Australian Legal Information Institute Website: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/ca1901124/

Commonwealth of Australia. (2016). Tourism Financing in Australia. Retrieved from the AUSTRAC Website: http://www.austrac.gov.au/publications/corporate-publications-and-reports/terrorism-financing-australia-2014

Cornish, D. & Clarke, R. (1987). Understanding Crime Displacement: An Application of Rational Choice Theory. Criminology, 25(4), 933-948. doi: org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1987.tb00826.x

Crime Investigation. (2015). Pablo Escobar. Retrieved from the Crime Investigation Website: http://www.crimeandinvestigation.co.uk/crime-files/pablo-escobar/crime

Drug Info. (2016). Drug Law in Australia. Retrieved from the Alcohol and Drug Foundation Website: http://www.druginfo.adf.org.au/topics/drug-law-in-australia#NEDs

Frontline. (2014). Background: al-Qaeda. Retrieved from the PBS Website: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/network/alqaeda/indictment.html

Haupt, D. A. (2009). Narco-Terrorism: An Increasing Threat to US National Security. National Defence UNIV Norfolk VA Joint Advanced Warfighting School. Retrieved from: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a530126.pdf

Hayward, B. (2016). Here’s how many people Pablo Escobar’s personal hitman has killed. Retrieved from the Unilad Website: http://www.unilad.co.uk/drugs/heres-how-many-people-pablo-escobars-personal-hitman-has-killed/

Hayward, K. (2007). Situational Crime Prevention and its Discontents: Rational Choice Theory versus the Culture of Now. Social Policy & Admin, 41(3), 232-250. doi: org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00550.x

Insight Crime. (2016, August 25). FARC. Retrieved from the Insight Crime Website: http://www.insightcrime.org/colombia-organized-crime-news/farc-profile

Jamal, T. (2016). Colombia (1964 – first combat deaths). Retrieved from the Project Ploughshares Website: http://ploughshares.ca/pl_armedconflict/colombia-1964-first-combat-deaths/

Makarenko, T. (2004). The Crime-Terror Continuum: Tracing the Interplay between Transnational Organised Crime and Terrorism. Global Crime, 6(1), 129-145. doi.org/10.1080/174405704200029702

Martin, G. (2012). Understanding Terrorism (4th ed.) [Google Docs]. SAGE Publications. Retrieved from: https://books.google.com.au/books?id=168ttmTMo5MC&pg=PA291&lpg=PA291&dq=motivating+ideology+for+narco+terrorism&source=bl&ots=UZjwnSoA2N&sig=vfc3QbCbPxOAaZv_D_nP2NKt_78&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj2sO7jndbOAhWBzpQKHWHLBkMQ6AEIITAB#v=onepage&q=motivating%20ideology%20for%20narco%20terrorism&f=false

Metzger, T. (2016). Social Movement Theory and Terrorism: Explaining the Development of Al-Qaeda. Retrieved from the Inquiries Journal Website http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/916/social-movement-theory-and-terrorism-explaining-the-development-of-al-qaeda

NarcoTerror.org. (2009). [null Lessons From History: Some Background Information On Narco-Funded Terrorism]. Retrieved from the Narco Terrror website: http://www.narcoterror.org/background.htm

National Security Council. (n.d). Transnational Organized Crime: A Growing Threat to National and International Security. Retrieved from the White House Website: https://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/nsc/transnational-crime/threat

Newsround. (n.d). How did al-Qaeda start? Retrieved from the BBC News Website: http://news.bbc.co.uk/cbbcnews/hi/find_out/guides/world/terrorism/newsid_2691000/2691445.stm

RAND. (2014). What America's Users Spend on Illegal Drugs: 2000 –2010. Retrieved from the rand.org Website: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR534.html

Roper. (2008). 'Buddy, circumstances make the man': Pablo Escobar's hitman 'Popeye' who admits ordering 3,000 murders breaks silence to say he doesn't feel ANY guilt... because he too was a victim of the 'King of Cocaine'. Retrieved from the Daily Mail Website: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3238278/Buddy-circumstances-make-man-Pablo-Escobar-s-hitman-Popeye-admits-ordering-3-000-murders-breaks-silence-say-doesn-t-feel-guilt-victim-King-Cocaine.html

Roy, R. L. (2014, August 10). Dissecting the Complicated Relationship between Drug Operations and Terrorism. Retrieved from the ‘thefix’ Website: https://www.thefix.com/content/dissecting-confounding-nexus-drugs-and-terror

Ruby, C. (2002). Are Terrorists Mentally Deranged?. Analyses Of Social Issues And Public Policy, 2(1), 15-26. doi: org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2002.00022.x

Speaker of the House of Representatives. (2006, January 3). One Hundred Ninth Congress of the United States. Retrieved from: https://www.rainn.org/pdf-files-and-other-documents/Public-Policy/Key-Federal-Laws/PL109-248.pdf

Thompson, G. (2015, December 6). The Narco-terror Trap. Retrieved from the ProPublica Website: https://www.propublica.org/article/the-dea-narco-terror-trap

TRAC. (2016). Narcoterrorism. Retrieved from the Tracking Terrorism Website: http://www.trackingterrorism.org/article/narcoterrorism

World Drug Report 2014. (2016). Drug use and its health and social consequences. Retrieved from the UNIDC Website: http://www.unodc.org/wdr2014/en/drug-use.html

Worldometers. (2016). Spending on illegal drugs this year. Retrieved from the Worldometers Website: http://www.worldometers.info/drugs/

External links

[edit | edit source]- How the DEA Invented "narco-terrorism". (YouTube, 2015)

- Ginger Thompson: Narco-terrorism: Terrorists in the drug trade? (YouTube, 2016)

- Rational Choice theory of Criminology (YouTube, 2016)

- Social movements - a primer: Toby Chow at TED Chicago (YouTube, 2013)

- Rational Choice Theory: Definition & Principles Quiz (Study.com, 2016)