Motivation and emotion/Book/2016/Exercise motivation and personality

How do personality traits influence a person's motivation to exercise?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

In 2011-12, 20% of Australian adults were classified as inactive, and 36% were classified as insufficiently active (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2013). With the growing worldwide obesity epidemic, and the lack of physical activity resulting from the technology boom, much research has focused on investigating individuals' exercise motivation, or lack thereof, with particular interest in how personality traits can account for such motivation. The purpose of this chapter is to answer the question "how do personality traits influence a person's exercise motivation?". In order to answer this question, relevant motivation and personality theories be discussed, followed by research investigating these theories in relation to personality and exercise behaviour. The chapter concludes with some ways in which this information can be used to increase exercise motivation and participation.

Motivation to exercise

[edit | edit source]

What is motivation?

[edit | edit source]

Motivation is the force that gives direction and energy to behaviour, operating at both the conscious and unconscious levels (VandenBos, 2015). At a conscious level, motivation refers to one's desire to pursue a goal or outcome and the ensuing effort an individual is willing to expend in order to achieve that goal or outcome (VandenBos, 2015).

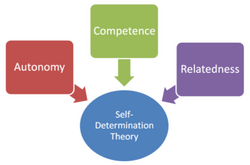

Self-determination theory

[edit | edit source]Self-determination theory (SDT) posits that there are three innate psychological needs that are the basis for self-motivation (Reeve, 2015). These needs are universal and instinctive; when satisfied, they allow for optimal function and growth, and furthermore, lead to the experience of intrinsic motivation (Reeve, 2015):

- Autonomy - the need to be the causal agent for events in one's life; to be able to self-initiate and regulate our actions, rather than be pressured by others to behave, think, or feel in a certain way. The perception of autonomous motives for exercise behaviour engagement may be a factor in adherence to such behaviours.

- Competence - the need to interact effectively with one's environment in order to grow and develop one's skills, and increase proficiency. Competence is the need that gives one the drive to seek out and take on challenges, and the energy to persist until the challenges have been mastered. A desire for increasing fitness could be related to the need for competence, therefore initiating exercise participation.

- Relatedness - the need to belong and interact with others, and form connections that involve mutual care and warmth. A desire to form new social bonds may result in one joining an exercise class or fitness group.

Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation

[edit | edit source]SDT distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, asserting that the self-determined individual will be driven by intrinsic motives (Reeve, 2015). Intrinsic motivation refers to the innate desire to extend oneself, and seek out new challenges (Reeve, 2015). Intrinsic motivation derives from the satisfaction of one's psychological needs, as well as from an inherent yearning for personal growth (Reeve, 2015). Intrinsic motives include curiosity, pride, and gaining a sense of achievement (see figure 3). In comparison, extrinsic motivation refers to the environmental incentives for performing a behaviour; that is, rewards and punishment, or the promise/threat of either (Reeve, 2015).

Furthermore, SDT maintains that there are differing degrees of extrinsic motivation, which reflect the extent to which a behaviour has been internalised, or assimilated into one's sense of self. These types of extrinsic motivation exist along a continuum, ranging from no autonomy (external regulation/controlled motives), to full autonomy (internal regulation; Reeve, 2015; see figure 4). The degree to which one engages in a task depends on the extent to which they are intrinsically motivated; the higher their intrinsic motivation, the more likely an individual is to perform a certain behaviour, as they perceive internal control and deem the behaviour to be enjoyable and satisfying (Reeve, 2015). It therefore follows that an individual with high intrinsic motivation (regulation) would be more likely to engage in exercise behaviours.

SDT and exercise behaviour

[edit | edit source]

Research by Wilson, Mack, Muon, and LeBlanc (2007) found all three needs to be good predictors of exercise behaviour intention. Similarly, Teixeira, Carraca, Markland, Silva, and Ryan (2012) found autonomy and competence to be related to exercise behaviour, whereby perceived competence determined engagement in exercise, and the stability of exercise motivation depended on the level of perceived autonomy (i.e., internal or external locus of causality). Unlike Wilson et al., however, Teixeira et al. did not find the need of relatedness to be a correlate of exercise behaviour, suggesting that all aspects of SDT may not apply to exercise motivation.

Evidence demonstrates that intrinsic motives are positively associated with exercise behaviour, while findings are mixed regarding the association between extrinsic motives and exercise behaviour (Teixeira et al., 2012); nonetheless, providing extrinsic motivators for an intrinsically motivating task undermines future experiences of intrinsic motivation (Reeve, 2015). Research suggests that controlled (extrinsic) forms of motivation, such as improving appearance, can explain why some people initiate exercise behaviours but do not follow through (Teixeira et al., 2012). Therefore, in order to sustain exercise motivation, intrinsic motives should be the driving force behind adopting a new exercise regime. For example, providing someone with a monetary reward for each exercise session will decrease the intrinsic value of exercising, therefore, when the monetary reward is no longer available, the person will no longer be motivated to exercise; incentives such as social engagement, challenge, and skill development are associated with prolonged exercise participation (Teixeira et al., 2012).

Quiz Time

|

Theories of personality

[edit | edit source]What is personality?

[edit | edit source]Personality is defined as the "consistent behaviour patterns and intrapersonal processes originating within [an] individual" (Burger, 2015, p. 4). That is, personality is not only the enduring set of individual differences in characteristics and behaviours that are consistent across both time and situations, but also the emotional, motivational, and cognitive processes that affect how one acts and feels (Burger, 2015; VandenBos, 2015). These individual differences and intrapersonal processes are not only shaped by external factors such as one's subjective experiences and cultural values (VandenBos, 2015), but also derive from within the individual (Burger, 2015).

Type theories vs. trait theories

- Introversion and extraversion

Trait theories

[edit | edit source]The trait theory argues that personality characteristics exist on a continuum that ranges from extremely low to extremely high, and furthermore suggests that any individual can be placed somewhere along this continuum for any characteristic (Burger, 2015). These personality traits are relatively stable and enduring internal characteristics that are inferred from an individual's attitudes, habits, and pattern of behaviours (VandenBos, 2015). For the purposes of this chapter, only the "Big Five" theory (five-factor model of personality) and Eysenck's theory will be discussed; these two theories are the most utilised for research on the relationship between personality and exercise behaviour (Rhodes & Pfaeffli, 2012).

Five-factor model of personality

[edit | edit source]The five-factor model (FFM) of personality asserts that there are five basic dimensions that make up human personality (hence, the "Big Five"; Burger, 2015):

- Openness to experience - distinguishes intellectually curious, imaginative people from cautious, conventional people. Open individuals are sensitive to the beauty of art and nature, and tend to think abstractly.

- Conscientiousness - distinguishes controlled, organised people from impulsive, unreliable people. Conscientious individuals are regarded as highly intelligent, and are able to think about future consequences before acting; they are valued for their dependability, however, can be seen as stilted and boring.

- Extraversion - distinguishes outgoing, energetic people from quiet, socially disengaged people. Individuals high in extroversion are fully engaged with the external world and enjoy action-oriented activities, while individuals low in extroversion are reserved and quiet, preferring solitary activities.

- Agreeableness - distinguishes considerate, friendly people from self-interested, sceptical people. Individuals high in agreeableness value social harmony and being helpful (they are very altruistic), and perceive others to be honest and trustworthy.

- Neuroticism - distinguishes emotionally unstable people from emotionally stable people. Neurotic individuals score highly on anxiety, depression, vulnerability, and self-consciousness; those at the other end are calm and free from persistent negative feelings.

Want to find out how you score on the "Big Five" personality traits? Click here to take the IPIP-NEO. NOTE: this is not a diagnostic tool.

Eysenck's theory of personality - Three dimensions of personality

[edit | edit source]Hans Eysenck proposed the existence of three superordinate trait dimensions:

- Extroversion-Introversion

- Neuroticism

- Psychoticism

Eysenck's theory takes a more biological approach to personality, asserting that physiological differences determine individual differences in personality (Burger, 2015). This is especially so for his extraversion-introversion dimension, for which he suggested that extroverts and introverts differ not only in their behaviour patterns, but also in their biological make-up, whereby each has a different base level of cortical arousal when in a non-stimulated state (Burger, 2015). He proposed that extroverts have a low cortical arousal level, and therefore seek out stimulation through social interaction and thrill-inducing activities; in contrast, introverts have a naturally high level of cortical arousal and a lower pain tolerance, and therefore, they prefer solidarity to avoid the unpleasantness of overstimulation (Burger, 2015). While research has failed to determine the difference in base-level cortical arousal, there is evidence to support Eysenck's notion that introverts and extroverts differ in their sensitivity to stimulation; for example, introverts are more responsive to chemical stimulants, such as caffeine, and are more intensely aroused by loud music (Burger, 2015).

Quiz Time

|

How does personality influence exercise motivation?

[edit | edit source]Now that we have covered the relevant theories of motivation and personality, let us turn to research examining the relationship between personality traits and exercise motivation, with particular emphasis on what has been found.

In a review of personality factors correlated to physical activity, Rhodes and Smith (2006) found the traits of extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness to be highly predictive of physical activity participation (where extraversion and conscientiousness were positively correlated, and neuroticism negatively correlated; McEachan, Sutton, & Myers, 2010). Moreover, the "big five" traits of openness and agreeableness, as well as Eysenck's psychoticism dimension, were unrelated to exercise behaviour motivation. Further to this, research shows that people who are addicted to exercise score higher on neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness, and lower on openness and agreeableness, compared to exercise controls (Lichtenstein, Christiansen, Elklit, Bilenberg, & Stoving, 2014). Additionally, Davis, Fox, Brewer, and Ratusny (1995) demonstrated that high scores on extraversion and neuroticism were positively associated with endorsement of physical exercise.

Some conclusions that can be formulated from these results include:

- People high in extraversion tend to seek out physical activity, whereas those low in extraversion tend to be less interested (Rhodes & Smith, 2006), perhaps due to the differing levels of sensitivity to stimulation, and the differing preferences for socialisation. While there is no evidence for why this occurs, it is logical to speculate that many exercise behaviours are too stimulating for introverts, and, due to their low pain tolerance, they will engage in such behaviours for shorter periods of time and be less motivated to maintain them.

- Those high in neuroticism are more likely to avoid or cancel plans for exercise (Rhodes & Smith, 2006), perhaps due to their high levels of anxiety and self-consciousness. Those who are more emotionally stable easily adopt and maintain exercise behaviours, possibly because they more readily satisfy their need for competence. Conversely, research shows neurotic individuals may become addicted to exercise; conceivably, exercise may provide a distraction from the unwavering negative emotions they experience, which may serve to increase their exercise motivation to the extent they become obsessed. Indeed, Davis et al. (1995) found neuroticism to be associated with mood improvement as a reason for exercise. Furthermore, neuroticism is associated with body dissatisfaction, thus, exercise addiction may be a result of appearance anxiety (Davis et al., 1995).

- Those high in conscientiousness are purposeful and self-disciplined, and are therefore more likely to adhere to exercise plans or goals. Those low in conscientiousness are impulsive, unreliable, and lacking in achievement motivation, and are therefore more likely to be irregular in their exercise patterns, often becoming bored and seeking out more thrill-inducing activities (Rhodes & Smith, 2006).

Self-determination theory

[edit | edit source]Ingledew, Markland, and Sheppard (2004) investigated whether the relationship between personality and exercise behaviour was mediated by the needs of SDT and the differing degrees of behavioural regulation, applying both the FFM and Eysenck's three dimensions theory. Consistent with previous research, they found that extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness were associated with exercise participation in relation to the SDT needs. Additionally, they found that each trait was correlated with differing degrees of behavioural regulation, whereby neuroticism was associated with introjected regulation, while extroverts and conscientious individuals were regulated by more intrinsic motives (Ingledew et al., 2004).

A study by Lewis and Sutton (2011) investigated autonomy as a mediating factor in the relationship between personality and exercise behaviours. They found that the degree of exercise participation was strongly correlated with behavioural regulation, such that exercise was positively associated with autonomous motives and negatively associated with external motives and amotivation (Lewis & Sutton, 2011). Furthermore, their results demonstrated that exercise participation frequency increased with the progression through the behavioural regulation continuum. Consistent with the large body of research on this topic, Lewis and Sutton found that extraversion was significantly correlated with exercise participation, concluding that increased energy and sensitivity to rewards encourages this increased behaviour engagement. Unlike previous studies, however, they found low scores in agreeableness to be associated with increased exercise frequency, determining that a self-focused perspective accounts for this finding (Lewis & Sutton, 2011). It should be noted, however, that they used gym attendance as a measure of exercise participation, and therefore, the relationship with agreeableness may not be replicated for team sports (Lewis & Sutton, 2011).

Similarly, Ramsey and Hall (2016) investigated the relationship between personality and physical activity, with a particular focus on assessing whether autonomy was a mediating factor. Indeed, they found that autonomy was significantly associated with physical activity, whereby autonomy was influenced by the traits of extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness (Ramsey & Hall, 2016). These findings suggest that personality does not directly influence exercise participation; rather, personality determines the extent to which psychological needs are satisfied and autonomous motives are perceived, which, in turn, affects exercise behaviour engagement.

Theory of planned behaviour

[edit | edit source]Another theory to explain the relationship between personality and exercise motivation is the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). The TPB asserts that the root of all autonomous and motivated behaviours is intentionality; the strength of one's intention to engage in a particular behaviour determines the occurrence of the behaviour (Rhodes, Courneya, & James, 2004; Wilson et al., 2007). Furthermore, the TPB argues that intention is determined by one's attitude toward the behaviour, the pressure to experience to perform that behaviour (subjective norm), and their perceived behavioural control (self-efficacy for performing that behaviour; McEachan et al., 2010).

Research demonstrates that exercise intention, and thus exercise behaviour, can be predicted by the activity trait (a key sub-trait of both extraversion and conscientiousness; Rhodes & Courneya, 2003; Rhodes et al., 2004). People who score highly on the activity trait tend to be energetic and talkative, preferring to live a fast-paced life, and so it makes sense that they would be more likely to engage in exercise behaviours, particularly activities that involve being quick on their feet (Rhodes et al., 2004; Rhodes & Pfaeffli, 2012).

Rhodes et al. (2004) split the attitude dimension of the TPB into affective attitude and instrumental attitude, finding that affective attitude was more strongly associated with exercise intention. They also found that the activity trait was positively correlated with all dimensions of the TPB, as well as exercise intention and behaviour. Furthermore, exercise intention and the activity trait together accounted for 75% of the variance in exercise behaviour (Rhodes et al., 2004).

Susan Davis-Ali, Ph.D. (as cited by Wagner, 2008, para. 5.)

Practical implications

[edit | edit source]Personality traits influence exercise participation in different ways, thus it is important to understand one's reasons for engaging in or avoiding exercise behaviours when designing an exercise program. Furthermore, significant consideration should be given to matching exercise type to personality, as this increases the adherence to, and the enjoyment of, the program.

Additionally, it is important to ensure that an exercise environment will provide support for the satisfaction of autonomy. Perceiving control over exercise behaviour will strengthen one's experience of intrinsic motivation, and will contribute to maintaining exercise participation. This is especially significant for those high in conscientiousness, as they like to be organised and in control of their environment. Having a strict exercise program to follow, which they help to design, could potentially satisfy, and provide great enjoyment to, conscientious individuals with a high need for autonomy. This will also contribute to their experience of exercise competence, and will further increase their internal regulation. As suggested by Ingledew and Markland (2008), exercise programs should seek to promote motives such as social engagement and health/fitness in order to foster autonomous, intrinsic motivation.

Matching personalities to exercise behaviours

Introverts may gain more enjoyment from lower-intensity, slow-paced, and more relaxing forms of exercise such as yoga or walking. Moreover, they are likely to prefer exercising alone, rather than in groups, to limit the amount of stimulation they are exposed to. For this reason, and also due to high intensity and competitiveness, introverts are less likely to derive pleasure from sports, particularly if they are team-based. Extroverts, particularly those high on the activity trait, would presumably gain enjoyment from high-intensity, fast-paced exercises, such as circuits and rpm classes, as well as energy-demanding sports, such as competitive running, cycling, or driving; they would also derive satisfaction from team sports or group fitness classes (e.g., Zumba), which would allow them to socialise. Furthermore, exercise behaviours that give the opportunity for them to listen to music would help to appease extroverted individuals' need for increased stimulation. Emerging from the growing research on this topic is the concept of "fitness personality", which involves determining the exercises that will best suit one's personality and the way they view exercise. While fitness personality is determined through type-based inventories, it can be a useful tool for individuals, personal trainers, and health practitioners to employ when developing exercise regimes that will foster interest and prolonged exercise motivation. Click here to find out your fitness personality. |

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]This chapter sought to answer the question "how do personality traits influence a person's motivation to exercise?". The self-determination theory of motivation, and the FFM and Eysenck's theory of personality, were first presented to provide a framework in which to answer this question. Research shows that the psychological needs of autonomy and competence are associated with exercise behaviour adoption and maintenance, and furthermore, demonstrates that intrinsic motives are better predictors of exercise participation than extrinsic motives. The need for autonomy appears to be a mediating factor in the relationship between personality and exercise behaviour, particularly for those high in extroversion and conscientiousness and low in neuroticism. Taken together, this research illustrates the importance of matching exercises to an individual's personality, and providing an environment that will satisfy autonomy and competence needs.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Exercise Motivation: How can we motivate ourselves to exercise? (Book Chapter, 2014)

- Exercise Motivation: How to get fitness motivation and how to keep it going (Book Chapter, 2011)

- Exercise and Motivation (Book Chapter, 2015)

- Group Motivation and Weight Loss (Book Chapter, 2016)

- Personality and Motivation (Book Chapter, 2010)

- Sport Psychology (Wikipedia)

References

[edit | edit source]Burger, J. M. (2015). Personality (9th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Davis, C., Fox, J., Brewer, H., & Ratusny, D. (1995). Motivations to exercise as a function of personality characteristics, age, and gender, Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 165-174. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(95)00030-A

Ingledew, D. K., & Markland, D. (2008). The role of motives in exercise participation. Psychology and Health, 23(7), 807-828. doi: 10.1080/08870440701405704

Ingledew, D. K., Markland, D., & Sheppard, K. E. (2004). Personality and self-determination of exercise behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(8), 1921-1932. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.08.021

Lewis, M., & Sutton, A. (2011). Understanding exercise behaviour: Examining the interaction of exercise motivation and personality in predicting exercise frequency. Journal of Sport Behavior, 34(1), 82. Retrieved from EBSCOhost database.

Lichtenstein, M. B., Christiansen, E., Elklit, A., Bilenberg, N., & Stoving, R. K. (2014). Exercise addiction: A study of eating disorder symptoms, quality of life, personality traits and attachment styles. Psychiatry Research, 215(2), 410-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.010

McEachan, R. R. C., Sutton, S., & Myers, L. B. (2010). Mediation of personality influences on physical activity within the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(8), 1170-1180. doi: 10.1177/13591053310364172

Ramsey, M. L., & Hall, E. E. (2016). Autonomy mediates the relationship between personality and physical activity: An application of self-determination theory. Sports, 4(2), 25. doi: 10.3390/sports4020025

Reeve, J. (2015). Understanding motivation and emotion (6th ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Rhodes, R. E., & Courneya, K. S. (2003). Relationships between personality, an extended theory of planned behaviour model and exercise behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology, 8, 19-36. Retrieved from EBSCOhost database.

Rhodes, R. E., Courneya, K. S., & Jones, L. W. (2004). Personality and social cognitive influences on exercise behavior: adding the activity trait to the theory of planned behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(3), 243-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S149-0292(03)00004-9

Rhodes, R. E., & Pfaeffli, L. A. (2012). Personality and Physical Activity. In E. O. Acevedo (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Exercise Psychology (pp. 195-223). Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rhodes, R. E., & Smith, N. E. (2006). Personality correlates of physical activity: a review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(12), 958-965. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.028860

Teixeira, P. J., Carraca, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(78). doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2015). APA dictionary of psychology (2nd ed.). Retrieved from University of Canberra ProQuest ebrary website http://site.ebrary.com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/lib/ucanberra/detail.action?docID=11033030

Wagner, G. D. (2008). Your fitness personality. Retrieved from https://experiencelife.com/article/your-fitness-personality/

Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E., Muon, S., & LeBlanc, M. E. (2007). What role does psychological need satisfaction play in motivating exercise participation? In L. A. Chiang (Ed.), Motivation of exercise and physical activity. Retrieved from http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2007-Wilson%20et%20al.%20-%20PNS%20and%20exercise%20motivation%20(Nova).pdf

External links

[edit | edit source]- Emily Balcetis: Why some people find exercise harder than others (TED talk)

- How to get motivated to exercise (Sanford fit webmd jr)