Motivation and emotion/Book/2014/Hoarding and motivation

What motivates hoarding?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Saving and collecting things is a completely normal behaviour. Nearly everyone has possessions they cherish and will keep forever, holding onto them to remind them of treasured memories. When the collecting of items becomes unhealthy and negatively impacts lives is when collecting may instead be the psychological disorder of hoarding. Hoarding is the acquisition of objects that hold little or no value, that clutter the home (or workplace, car, yard etc.) to the point that it may become unusable (Shaeffer, 2012). People who hoard often experience extreme difficulty in letting things go and discarding items, and experience significant stress and impairment in activities and relationships due to their behaviours (Shaeffer, 2012). Hoarding has the potential to become a very detrimental habit in people's lives, and often effects lives in many negative ways. What actually motivates hoarding has been the subject of much study, and can be difficult to interpret. The motivating factors in hoarding are vital in attempts to understand the disorder and to effectively implement treatment options. Hoarding is unique in that there is multiple motivating factors behind it, in a wide variety of situations.

The cluttered living conditions of hoarders can be dangerous and pose as health risks. Cluttered homes that hoarders live in increase the chance of experiencing a fire by 47%, a fall 38%, hygienic illness by 35%, and are only 25% likely to experience no hazards (Mogan, 2009). These statistics show just what a dangerous disorder hoarding is.

Hoarding was long regarded only as a symptom of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Recently, hoarding has developed much more attention as a stand alone public health issue that effects more people globally than once thought. Although this is the case, much of the research done into hoarding is done so with reference to OCD, as the two disorders are closely related.

The aim of this book chapter is to educate about what hoarding actually is, what factors motivate hoarding, and what contributes to the disorder occurring. An introduction of the theories of hoarding, a list of common symptoms and characteristics of hoarders, treatments of the disorder, a look at a case study and diagnosis will all be detailed to contribute in answering the question of what motivates hoarding.

Theories of hoarding

[edit | edit source]In 1908 Freud first declared that hoarding represented a failure in the psychosexual stage progression (Grisham & Barlow 2005). Freud also claimed that hoarding of money reflected the parsimony in the anal component, the second stage in Freud's theory (Frost, Sketekee, 1998). Modern theory of Freud's work discusses a lack of mental flexibility and adaptiveness in people that hoard, out of fear and hate of change and unpredictability (Mogan, 2009).

Table 1.

Freud's Anal stage of psychosexual development

| Stage | Age Range | Consequences of psychologic fixation |

|---|---|---|

| Anal | 1-3 years | Anal retentive: Obsessively organised, or excessively neat Anal expulsive: Reckless, careless, defiant |

On the back of Freud's initial study on conflict in the anal stage, Fromm (1947) proposed that people acquire possessions as a way of relating to the world around them. He suggested hoarding was characterised by remoteness and withdrawal from others, compulsiveness, suspiciousness, cleanliness, extremes of order, and concerns about punctuality. People who hoard are thought to feel a sense of security from collecting and holding on to objects, and form attachments to items, rather than people (Grisham, Barlow, 2005).

Hoarding has also been linked with the evolutionary theory, as collecting goods ensures survival when supplies are scarce, and is therefore an evolutionary adaptive behaviour in humans (Grisham, Barlow 2005). Hoarding has also been found to be the result of avoidance of the anxiety associated with decision making and throwing away items. The hoarding behaviours are positively reinforced as the retained possessions leave a comforting and pleasurable effect on the hoarder (Grisham, Barlow 2005). Researchers Frost and Steketee (1998) found that hoarding behaviour can be attributed to four types of deficits: information processing deficits, emotional attachment to possessions, emotional distress, and the avoidance behaviours that occur as a result.

Early pyschologists incorporated hoarding into theories of psychopathology, suggesting that hoarding comes from a perfectionistic strive to gain control over the environment (Frost, Steketee, 1998). To achieve this desired control, hoarders feel they must not throw away any object that may be needed for the future. As they future is impossible to predict, hoarders thus keep everything as the safest option (Frost, Steketee, 1998).

Psychologist Melanie Klein proposed the human unconscious urge is to 'return' everything that has been taken from the mother, but in turn creates an un-resovable conflict in the human compulsive urge to 'hold on' to everything, which may relate to the theory and motivation behind why people hoard (Hinshelwood, 2012).

The cognitive behavioural model discusses a faulty appraisal of what is and isn't important items (Mogan, 2009). The cognitive behavioural model suggests that there may be a disability directly associated with the clutter, poor decision making, and emotional behaviour (Mogan, 2009).

Table 2

Mogan's (2009) Psychological Models of Hoarding

| Abnormal psychology model | Squalor model | Addiction model | Attachment model | OCD model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weird reasons for keeping things. Claim special relationships with objects | Dementia and similar diseases emphasise loss of care and organisation. | Impulse control issues. Totally focused on hoarding. | Unconditional love and attachment to objects. | OCD controls hoarding. E.g., believes must hoard to prevent harm. |

Symptoms and characteristics

[edit | edit source]The main symptom and characteristic of hoarding is the obvious inability to discard of objects. Hoarding behaviour though can take shape in a variety of different ways, and is often observed in unique and rare situations. When diagnosing hoarding, it is important to distinguish between hoarding and collecting. Generally, collectors display their items with a sense of pride, and enjoy discussing and sharing with others about them. The items are normally kept tidy and in good condition, and no detrimental financial strain is normally achieved by collecting. In comparison, hoarders generally experience embarrassment, disgust and shame about their items, and financial strain is usually acquired by obtaining all the items.

Common characteristics of a hoarder include:

- Difficulty in getting rid of items

- Extremely cluttered home/workplace/yard/car

- Refusal to let people into their home

- Losing important items in the clutter

- Unable to organise possessions

- Denial of a problem

- Unrealistic beliefs about importance and value of an item

- Feeling responsible for items, even thinking they may have feelings

Items commonly hoarded:

- Books and newspapers

- Furniture

- Clothing

- Animals

- Garbage/rotten food

Often consequences from hoarding:

- Poor health and safety for those living near the clutter

- Financial strain

- Conflict with family and friends

(Bratiotis et al, 2009).

Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]Classification in the DSM

[edit | edit source]Original versions of the DSM only listed hoarding as symptom of OCD, and not as its own distinct disorder. The DSM-5 published in May 2013 was the first edition to refer to hoarding as its own disorder, referring to it as 'hoarding disorder' (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM is the handbook used by health care professionals around the world to diagnose mental disorders.

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder are:

A. Persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of the value others may attribute to these possessions. (The Work Group is considering alternative wording: "Persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.")

B. This difficulty is due to strong urges to save items and/or distress associated with discarding.

C. The symptoms result in the accumulation of a large number of possessions that fill up and clutter active living areas of the home or workplace to the extent that their intended use is no longer possible. If all living areas become decluttered, it is only because of the interventions of third parties (e.g., family members, cleaners, authorities).

D. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (including maintaining a safe environment for self and others).

E. The hoarding symptoms are not due to a general medical condition (e.g., brain injury, cerebrovascular disease).

F. The hoarding symptoms are not restricted to the symptoms of another mental disorder (e.g., hoarding due to obsessions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, decreased energy in Major Depressive Disorder, delusions in Schizophrenia or another Psychotic Disorder, cognitive deficits in Dementia, restricted interests in Autism Spectrum Disorder, food storing in Prader–Willi syndrome) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Prevalence rates

[edit | edit source]Lack of previous epidemiological studies has made it hard to know exactly how prevalent hoarding is among the population. Although exact statistics may be unknown, Brown and Meszaros (2007) claimed that hoarding in the general population is rare. Hoarding is still common enough to be regarded as a public health problem, and because of the high rates of hoarding in sufferers of other psychological disorders, it still has a strong presence. It is estimated that the overall population suffering from hoarding is around 2 to 5% (Shaeffer, 2012). In Australia, it is estimated that hoarding is prevalent in 1 in every 350 to 400 people (Mogon, 2009).

Causes: What motivates hoarding?

[edit | edit source]Hoarders experience problems in their decision making that impedes their ability to discard objects (Shaffer, 2012). Often, something that motivates hoarders is to collect items that they believe have a nostaligic effect and mean something personal to them worth keeping (Melamed et al, 1998). When this behaviour becomes more severe and looses its innocence, hoarders begin to stop making excuses for themselves (Melamed et al, 1998). Hoarders may also often buy and stock up on extra and unneeded items as a precaution 'just incase' they may need them in the future (Frost, Sketetee, 1998).

Safety and comfort is also a huge motivating factor in hoarding. The huge collection of objects a hoarder may possess often will represent a place of safety for the hoarder, with each possession associated with happiness and comfort (Frost, Hartl, 1996). When hoarders acquire new possessions, these positive and happy feelings are produced again, and the thought of discarding items may violate the positive and comforting thoughts (Frost, Hartl, 1996). Hoarders attempts to maintain these comforting and happy feelings is a huge motivation for them to hoard items.

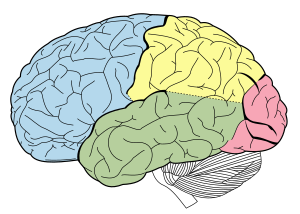

Brain pathology of individuals has shown possible links between brain activity and the motivation behind hoarding. A study of patients with OCD who were also hoarders revealed a lack of glucose metabolism in the posterior cingulate gyrus, dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, and cuneus in the brain (Brown, Meszaros, 2007). Hoarding may arise when fronto-subcortical circuits in the brain that normally inhibit this behaviour, are interrupted (Brown, Meszaros, 2007). The drive to collect and gather items originates in the subcortical and limbic portions of the brain, showing the importance of the brain in the behaviour of collecting items (Anderson, Damasio, Damosio, 2004). The prefrontal cortex is vital for humans determining what items are worth keeping, and what items are worth discarding. The prefrontal cortex is important in organisation, decision making, and information processing, so any damage to it may contribute to the motivation for people to hoard (Anderson, Damasio, Damasio, 2004). Another possible unconscious motivating factor for hoarding is the role genes have to play. People suffering from hoarding are much more likely to have close relatives who also hoard, than those who do not (Brown, Meszaros, 2007).

Another interesting potential motivator for hoarding is people who have experienced hardship or poverty in their life. Living through tough times instills an extreme appreciation for objects in some people, as whether or not they would be able to get new items in the near future became unclear (Bratiotis et al, 2009). This was particularly the case for people who survived wars, as that was a period of time where poverty was rife and supplies scarce everywhere. In some instances, the strong appreciation for possessions developed further into hoarding disorder as people didn't re-adjust even after supplies became readily available again (Bratiotis et al, 2009).

Differences among gender

[edit | edit source]Females are more likely to develop hoarding than males in OCD and dementia sufferers (Starch, 2011). There has though been little research into gender differences and their role on the motivation of hoarding, as well as if one gender is more likely to hoard than the other. Frost et al (2008) found in their study that gender roles usually do not have much of an impact in hoarding, and it was generally evenly split between males and females.

Difference among cultures

[edit | edit source]Cultural factors in hoarding has made the definition in some instances subjective. All people own items and often collect things, but defining 'too much' or 'too little' is often needed to be culturally defined (Shaeffer, 2012). There is a lack of research comparing different cultures and their characteristics of hoarding. There was a study conducted into hoarding in Japan in comparison to hoarding in Western cultures, which revealed hoarding in Japan was similar to elsewhere in motivations towards hoarding (Stein et al, 2010).

Age and hoarding

[edit | edit source]Melamed et al, (1998) found that hoarding is more common and often found in elderly people, especially those who have suffered a close and personal loss such as the death of a loved one. Another major contribution for increased hoarding rates in the elderly is that they are much more likely to self-neglect themselves (especially if widowed and sole dependent), which can contribute to hoarding and thus lead to other health problems (Brown, Meszaros, 2007). Motivation for hoarding in elderly people seems to not be deliberate, instead often an accidental side effect from being lonely and self dependent.

There is also research into hoarding in children, and the effects it may have on their development. Storch (2011) stated that many adult suffers of hoarding displayed symptoms during their childhood, and if more research was focused into hoarding in children then the behaviour may be extinguished before adulthood. Hoarding in children may be just as prevalent as adults, but is also more constrained, with children tending to hoard their items in a much smaller space (bathroom or bedroom) and supplies generally harder to obtain due to the limited resources children have (Storch, 2011).

Although serious hoarding does not normally start until early teens, the most common age for people being treated is 50 years old, and they have most likely been suffering from hoarding most of their adult life (Bratiotis et al, 2009). Hoarding symptoms tend to be mild in sufferers 20s, but by mid 30s symptoms generally reach extreme (Mogon, 2009).

Relationship with other psychological disorders

[edit | edit source]Hoarding has long been associated with other psychological disorders such as Prader-Willi syndrome, tic disorders, mental retardation, obsessive compulsive disorder and even traumatic brain injury (Brown, Meszaros, 2007). The motivation for people to hoard may come from other psychological disorders they are simultaneously suffering from, that contribute and increase the motivation to collect items. One study showed that 22% of hospitalised dementia patients engaged in significant hoarding (Brown, Meszaros, 2007). Other statistics involving dementia patients have also shown the correlation between the two disorders, with regular findings of dementia sufferers hoarding in over 5% of cases (Brown, Meszaros, 2007).

Before hoarding received its own classification in the DSM manual, it was featured purely just as a symptom of obsessive compulsive disorder, indicating just how strong the correlation between the two disorders is. Hoarding was often just considered as a specific type of OCD. Brown and Meszaros (2007) stated that between 25-30% of OCD sufferers have significant compulsions of hoarding. There has long been a debate about whether or not hoarding is simply a manifestation of OCD. Rachman et al (2009) found in their study that although there are many similarities between the two disorders, the differences far out weight them. They argued the two disorders should be viewed separately, in order to advance clinical work and potentially help understand, treat and know what motivates hoarding better (Rachman et al, 2009).

|

Case study Dee is a 63 year old divorced women who describes her hoarding problem as 'difficulty in throwing things away'. Due to her hoarding her house has become extremely cluttered, and she suffers from complete social isolation as she is too embarrassed by all of her belongings everywhere. Dee admits that her hoarding began in childhood, and she also states that she was a very nervous and anxious child. Dee has sought treatment to try to extinguish her hoarding. To treat Dee, an intensive treatment program was implemented, consisting of 4 hours a day, 5 days a week, for 6 weeks. This treatment was a form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which involved Dee constantly setting goals, learning about hoarding behaviour, and cognitive restructuring. Through the program, Dee begun de-cluttering her home, sorting through items, and getting it into a state where she could invite people into her home, which helped rid her social isolation. When learning to throw items out, Dee challenged her nerves about terrible things happening if she threw things out. Dee's treatment was successful and she could begin to start living a normal and fulfilling life. (Pogosian, 2010)

|

Treatment of hoarding

[edit | edit source]Hoarding is a notoriously hard condition to treat. Often hoarders have become deluded with their unhealthy habits, and may not appreciate the severity of their problem. Because of this, it is often family members, friends or disgruntled neighbours (in cases of hoarding in the yard of a house) who bring the disorder to attention to seek help (Melamed et al, 1998). Hoarders are seen as secretive, often go undiagnosed for years, detest treatment and are usually in denial, all factors that make treating hoarding difficult (Mogan, 2009). Treatment of hoarding has a high drop out rate (Frost et al, 2009). Hoarders have very personal and complex reasons for their behaviours, thus making treatments for them difficult and often requiring unique and specific treatments (Mogon, 2009). Frost et al (2009) found that cognitive behavioural treatments that are normally very successful in the treatment of OCD, were not very successful in treating hoarding.

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy

[edit | edit source]Although it is still presented with numerous challenges, CBT is regarded as the best method for treating hoarding (Gilliam, 2010). As demonstrated in the real life case study above, CBT can see remarkable results when attempting to treat hoarding. In this example though, Dee was a highly motivated hoarder who was fully committed in treating herself. With the high dropout rate, and denial and unwillingness to participate, CBT is often hard to successfully administer. Gilliam (2010) found that one of the most successful ways to treat hoarding is to make them participate in behavioural experiments, as it is a proven way of getting clients to challenge their own thinking and question the value of their possessions. Attempts to directly challenge the clients beliefs usually ends in arguments and negation, rather than permanent changes in thinking and behaviour (Gilliam, 2010). All cases of hoarding are circumstantial, and therefore treatments should be administered uniquely to give successful extinguishment the best shot.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Hoarding is a serious psychological condition that has the potential to greatly impact lives. Hoarding is motivated by a wide variety of factors, mainly cognitions about personal possessions, as well as certain brain functions that can influence decision making and thought processes regarding items. Other known psychological conditions such as OCD and dementia are also known to greatly increase the chances of motivation for hoarding to occur. Although treatment can be difficult to administer, with the recent inclusion of hoarding as its own disorder in the DSM and increased research into the condition means potential new treatment could be on its way. With this recent exposure into hoarding, we are in a much better position to understand what truly motivates people to hoard.

Quiz to finish- what did you learn?

[edit | edit source]

Hoarding in popular culture

[edit | edit source]Recently hoarding has seen a popular following through the form of television. Multiple television programs have been created based around documenting peoples living situations around hoarding disorder. The shows have been very popular, as people view often fascinating hoarding situations that need to be viewed to be truly believed. Television programs Hoarders and Hoarding: Buried Alivehave especially become very popular around the world, and in turn have raised awareness about hoarding and what a serious health issue it is. For links to some of the videos about hoarding view external links.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Compulsive hoarding

- Hoarding

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

- Anal stage

References

[edit | edit source]Anderson, S. W., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2005; 2004). A neural basis for collecting behaviour in humans. Brain : A Journal of Neurology, 128(Pt 1), 201-212. doi:10.1093/brain/awh329

Bratiotis et al. (2009). International OCD Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.ocfoundation.org/uploadedFiles/Hoarding%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf?n=3557

Brown, W. MD. Meszaros, Z (2007). Hoarding. Psychiatric Times, 24(13), 50

Frost, R. O., & Hartl, T. L. (1996). A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(4), 341-350. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2

Frost, R. O., & Steketee, G. (1998). Hoarding: Clinical aspects and treatment strategies. Obsessive compulsive disorders: Practical management, 533-554.

Frost, R. O., Tolin, D. F., Steketee, G., Fitch, K. E., & Selbo-Bruns, A. (2009). Excessive acquisition in hoarding. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(5), 632-639. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.013

Gilliam, C. F. (2010). Compulsive hoarding. Bulletin Of The Menninger Clinic, 74(2), 93-121.

Grisham, J., Barlow, D. (2005). Compulsive hoarding: Current research and theory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 45–52. doi:10.1007/s10862-005-3265-z

Hinshelwood, R. D. (2012). Kleinian theory. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 93(3), 497-499. doi:10.1111/j.1745-8315.2012.00567.x

Melamed, Y., Szor, H., Barak, Y., & Elizur, A. (1998). Hoarding-what does it mean? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 39(6), 400-402. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90054-2

Mogan, C. (2009, November 5-6). The Psychology of Compulsive Hoarding. Speech presented at the National Squalor Conference, Sydney.

Pogosian, Lilit. 2010. Treatment of Compulsive Hoarding: A Case Study. The Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine 25/26: 8-11. Retrieved from http://www.einstein.yu.edu/uploadedFiles/EJBM/page8_page11.pdf

Rachman, S., Elliott, C. M., Shafran, R., & Radomsky, A. S. (2009). Separating hoarding from OCD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(6), 520-522. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.014

Shaeffer, M. K. (2012). A Social History of Hoarding Behavior (Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University).

Stein, D,. Matsunaga, H., Hayashida, K., Kiriike, N., Nagata, T. (2010). Clinical features and treatment characteristics of compulsive hoarding in Japanese patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr, 15(4), 231-236.

Storch, E. B. (2011). Compulsive hoarding in children. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 507-516. doi:10.1002/jclp.20794