Motivation and emotion/Book/2014/Feedback for learning motivation

What is the role of feedback in motivating people to learn?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

What will motivate me to achieve? Is feedback essential? If so, what type of feedback will help me to get the most out of my learning experience? The aim of this chapter is to use psychological theory and relevant knowledge from the literature, to assist the reader to develop a better understanding of this area and ultimately improve their life in the process...

In the field of motivation and emotion, learning and our motivation to learn is highly researched. Feedback and how it impacts our motivation to learn, depends largely on what motivates us in the first place. The motivation to achieve something is a basic need in our psychological wellbeing. There are different types of motivation, and there are many theories underpinning them. To determine what is your most effective motivator, it is important to first know what your motivation is to obtain a certain outcome in the first place. This varies depending on what the task is (i.e. cleaning your house, receiving an A-grade in a school subject, or winning a gold medal at the Olympics). Motivation is an important determinant of behaviour in learning, regardless of the context.

Can you think of a time that you have needed help with a task, and someone has given you feedback during the process. Was it helpful? If so, what was it that helped? Or was it that they made you feel good about yourself so you just kept going?

What we know from research is that if you received feedback that was just praise, such as "you're doing great", it may not necessarily have been effective or constructive. However if the provider of feedback says "how about you try this", then it is more likely to help you improve your processes and make positive progress (Skipper & Douglas, 2012).

What is the use of feedback if it isn't effective??

What is feedback?

[edit | edit source]Definition

[edit | edit source]Feedback is a broad term with varied meanings depending on the domain. In psychology it is defined as 'information provided by an agent regarding aspects of one's performance or understanding' (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p81). There is a body of literature in the field of psychology that discusses feedback, what constitutes feedback, the impact of feedback, and how best to deliver it (Carpentier & Mageau, 2013; Hattie, 2012; and Price, Handley, Millar & O'Donovan, 2010). It is generally agreed across the field that feedback has the opportunity to influence motivation, job satisfaction, self-awareness, learning, and performance.

Different types of feedback and their consequences

[edit | edit source]Kluger & DeNisis (1996) were interested in looking at the outcomes that different feedback has on people's learning experiences. They identified two distinct types of feedback that are used in the learning context. Promotion oriented feedback (previously referred to as ‘positive feedback’) confirms and reinforces desirable behaviours. This is useful for young people learning new tasks, or for learners that are not confident trying something different. The alternative is change oriented feedback (previously termed ‘negative feedback’), which is used when performance is inadequate and needs to be modified in order to achieve the individual’s goals (Carpentier & Mageau, 2013). Both of these types of feedback can have positive and negative outcomes, which is why the newly defined terms are more accurate. There are times when promotion oriented feedback is not as valuable as change oriented feedback. For example, when professional athletes receive feedback directed at improving their technique (change oriented), this assists to increase their motivation and well-being (Carpentier & Mageau, 2013, p424). In this circumstance, promotion oriented feedback would not be as effective.

There are three primary feedback functions: cognitive, motivational, or metacognitive (see Harks, Rakoczy, Hattie, Besser, & Klieme, 2014, for further details). Within these there are single feedback characteristics. Process-oriented feedback is a type of feedback that educators use that assists to help student's follow accurate processes in order to achieve the task. Grade-oriented feedback on the other hand, is when teachers provide feedback on a student's work based on a grade (such as A, B, C). Although grade-oriented is predominantly used in secondary education, process-oriented has been proven to be highly beneficial, and has more positive indirect effect on student's interest and achievement than grade oriented feedback due to its perceived usefulness (Harks et al, 2014).

- Question: If you were helping a 5 year old learn how to tie their shoelaces, what would be the best type of feedback to give them?

- Answer: Process oriented feedback, so that the child can learn the process of how to tie their lace.

| Feedback or feedforward? | |

|---|---|

|

Delivery of feedback

[edit | edit source]

There are different ways that feedback can be delivered to an individual (Skipper and Douglas, 2012). Feedback can be related to the task, which is focused on correct or incorrect performance; it can be about the processing of the task, giving feedback on how it was completed; about self-regulation, helping the individual to develop better awareness of the learning process; or about the self, either praise or criticism of the individual (p328). The findings supported the notion that when a learner is succeeding at their task, they respond equally positively to receiving feedback about themselves, about the process they are following, and receiving no praise at all. There was a difference in the response to feedback conditions when the learner was failing at their task, those receiving person praise showed less positive response than those who received process praise. So does this mean that when we are being unsuccessful at something that we should only seek praise on the process we are following? There are other issues to consider.

There is substantial research in the field about how to be effective in your delivery of feedback. It has been found to be a common denominator in the top influences on how people learn from experience (Hattie, 2008). Coaches and educators can be confused believing that any kind of feedback is helpful to a learner, this is not always the case. Some types of feedback can have a positive influence on learning, some can have a negative influence, and some can have no influence at all (Skipper & Douglas, 2012). The following list of suggestions has been compiled from recent studies which cover the fields of feedback in sport and education (Carpentier & Mageau, 2013; Hattie, 2012; and Price et al., 2010):

- feedback should be given in an empathic, considerate tone of voice;

- it should give choices for solutions and be paired with 'tips', as opposed to blunt direction;

- it must be based on clear and attainable outcomes, not goals that are impossible for the learner to achieve;

- it should avoid person-related statements, so that the learner does not contribute the comments to themselves and take the statement personally as an insult or knockdown;

- consist of clear goals;

- the content of the feedback must be applicable and provided in a timely manner;

- the relationship between the student and the assessor is core;

- the student needs to understand the feedback; and

- the feedback needs to match the learner's needs.

For a discussion on the importance of feedback and the impact on student learning, watch this video: Feedback on Learning - Dylan William

Issues about feedback

[edit | edit source]

When providing and receiving feedback, there are some issues that need to be taken into account (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p98):

- The timing of feedback must be considered, as immediate feedback versus delayed feedback can play a significant role in the outcome depending on the type of feedback being delivered. For example when receiving feedback in a testing situation, it is beneficial for feedback to be delayed, whereas if you are following a process incorrectly, immediate feedback is most helpful.

- The difference between the effects of promotion focused feedback (previously positive feedback), and prevention focused feedback (previously negative feedback). Prevention focused is considered more powerful when directed at the self, whereas both types are beneficial when reinforcing the task being undertaken. There are varied effects relating to student commitment, mastery or performance orientation (this is explained below under the sub-heading 'goal setting in learning motivation'), and self efficacy, when delivering feedback at the self-regulation level.

- The environment that the feedback is being provided in plays a large part in how well the feedback is received. For example the climate of the classroom is critical. If students feel they are under pressure to perform they can often be scared to take on board or even listen to feedback provided by their teacher, regardless of how it is delivered or what is said. On the other hand, certain environments require the teacher to provide feedback in a harsh, direct manner (such as the Defence Force as pictured).

- Finally, feedback for assessment purposes is imperative in that it provides information and interpretations about the difference between a student's current status and the goals the learner is working toward. If this is not the case, the assessment piece does not add value to the student’s learning outcomes. From these four commonly debated issues about feedback, it is evident that the type of feedback provided plays a huge part in our learning process and how successful we are at making progress after receiving the feedback.

| Feedback in the workplace |

The application of feedback and how it motivates you in the workplace can have massive implications. Learning new processes and tasks at work, particularly when you have been employed for a while, can be difficult to achieve. While you would expect that your work motivation would increase after receiving positive feedback, findings from research are inconsistent regarding the motivational effect of feedback (Jarzebowski, Palermo & van de Berg, 2012, see below 'theory in focus'). An interesting discussion on feedback for employees is considered by Bill Gates in this TED talk. |

|---|

Is feedback essential?

[edit | edit source]So far we have looked at the different consequences feedback can have on a person's learning process, considered ways feedback can be delivered, and reviewed issues to take into account with regards to providing feedback. Now we question: is feedback essential in our motivation to learn? The answer is yes and no! We can be motivated to achieve something, and we can continue to be motivated and continue to learn, regardless of whether we receive feedback or not. The problem is, if we are learning something new and don't receive comments from others about our progress, we could be going in the completely wrong direction and not even realise it! Just imagine (or recall) you are 16 years old and learning how to drive a car for the first time. How would you go if you were doing it with only an instruction booklet and no one providing feedback on turning left, right, reverse parallel parking etc. What about having someone to remind you to stop at a stop sign, or give way to your right (in Australia). Do you think you would be successful at passing your test to obtain your Learner's permit? Most of us would say 'no'! An extensive review of literature on the effects of educational influences and interventions on student achievement was undertaken by John Hattie in 2008. From this, he recommended that effective instruction can not take place without feedback from student to teacher on the effectiveness of their instruction. This suggests that in the feedback process, it is essential that students are able to provide their teacher with feedback in order for them to achieve the best outcomes in the learning process.

|

- Question: when providing or receiving feedback, can you recall what are the four issues to be taken into account?

- Answer: timing, effects, environment, and assessment purpose.

Motivation and goals

[edit | edit source]Motivation defined

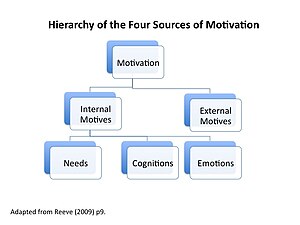

[edit | edit source]To be motivated means to be moved to do or achieve something (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p54). As human beings we are naturally motivated to interact with the environment to advance personal growth, social development, and psychological wellbeing (Reeve, 2009, p142). What motivates one person will not necessarily motivate another. It can depend on whether you are doing something for the enjoyment of it or to achieve something at the end. Motivation and goal setting go hand in hand. You can not achieve a goal without being motivated, and if you are motivated to achieve something you must have a goal in mind that you are working towards.

Motivational theories

[edit | edit source]Our natural motivation to learn, grow and develop is referred to as the organismic approach to motivation. Study in the field of motivation is vast. What the research refers to as Cognitive Approaches to Motivation, are theoretical concepts that have been developed that identify the underlying processes present in motivation. There are two key motivational orientations. If you are primarily focused on achieving a goal in order to reduce the distance between your current situation and your future desired situation, then you are promotion focused. However if you are motivated to increase the distance between the failure you have experienced and your current state, then you are prevention focused. Jarzabowski et al., (2012) reviewed findings in the area. They reported that positive feedback increased outcomes such as motivation, performance and effort for individuals in promotion focus but not in prevention focus, whereas negative feedback increased the same outcomes in prevention focus but not in promotion focus.

Activity - to wrap your head around motivation theory in practice, have a go at completing this practical exercise on student motivation. If you are not currently a student, imagine you are considering tertiary study and then complete the following activity - University student motivation exercise

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are widely recognised and discussed throughout the literature in this domain (see Ryan & Deci, 2000). If there is an external motivation for you to achieve something, for example cook dinner to please your partner, you have what is termed extrinsic motivation to achieve the outcome of the prepared meal. If you are cooking dinner for your partner for the joy of preparing and cooking dinner, you have intrinsic motivation to achieve the outcome of the meal.

When you are reflecting on what it is that you want to achieve, it is helpful to know what is motivating you. There are times when an intrinsic desire to achieve will drive you further than an extrinsic desire, and vice versa. For example, if you have agreed to go to the gym everyday with a friend, and the only way you are driven to exercise is if you are visiting the gym with your friend, you are extrinsically motivated to exercise. If your friend stops going to the gym with you, you are less likely to go to the gym, hence less likely to exercise. You can see in this example that an intrinsic motivation to exercise would better assist you to obtain your goal than an extrinsic motivation.

As human beings, we have a system of primary, or innate, basic psychological needs. One of the key theorists to develop a model on this was Abraham Maslow, who first published his ideas of an individual's heirarchy of needs in 1943. Since this time there has been extensive development of the concept. Self-Determination Theory (also referred to as Cognitive Evaluation theory) is one such development. It suggests that there are three essential needs that are important for wellbeing and psychological growth. These are competence, the psychological need to be effective in interactions with the environment; relatedness, the desire to be connected and feel accepted by others; and autonomy, the desire to be able to initiate your own actions in accordance with your personal sense of self. These core needs are considered essential for a variety of developmental processes, including the development of interest (Krapp, 2005).

The role of interest in our motivation to learn

[edit | edit source]Interest is considered a variable of motivation. If we are interested in a topic, we are more likely to want to learn about it. Hidi (2006) found that when students were interested in what they were doing, they were more likely to have optimal motivation to complete the task. 'In contrast to many other motivational concepts, interest is characterized by its content or object specificity' (Krapp, 2005, p382).

The development of interest depends on a person's interaction with the object or activity they are focused on. To begin with their interest may be predominantly on a domain specific situational interest, but later on it may develop into a relatively stable individual interest of high personal relevance (Krapp, 2005). For example, when you are at school and are first introduced to the concept of biology because it is a core subject, you might be interested in it because it is something that reminds you of your experiences as a small child playing with fish in your fishbowl. As time goes on, and you continue to choose Biology as an elective subject in your higher education and then as a tertiary university course, your interest goes beyond high school biology and leads to a career in agriculture.

|

Goal setting in learning motivation

[edit | edit source]Goal setting is an essential aspect in achieving learning outcomes. We need to have goals that we are working towards in order for feedback to be valuable, if we don't then there would be no interest in improvement, making the feedback invalid. Locke, Shaw, Saari, & Latham (1981) discussed feedback as needing to be provided in a timely manner and in relation to the goal.

From research we know that there are different types of goals (see Senko & Harackiewicz, 2005). Achievement goal theory proposes that when a student has goals, they have a framework with which they establish a purpose for learning, an approach to academic activities, and performance (Hidi, 2006). If you set a goal to outperform your peers, it is classified as a performance goal, defining success versus failure by comparing yourself to others. There are two different performance goals: performance–approach goals (seeking success) or performance-avoidance goals (avoiding failure). On the other hand, if you are focused on developing skills, you are pursuing a mastery goal, whereby success is defined by comparing your own history and experience of knowledge and skill development (termed 'self-referential standards'). Feedback can affect multiple goals in the same direction, or affect one goal but not the other (Senko & Harackiewicz, 2005, p328).

- Activity - try this goal identification exercise to assist you to reflect on your own goals.

| Feedback in sport | |

|---|---|

|

Theory in focus

[edit | edit source]The predominant research in the area of feedback on learning has emerged during the twenty-first century. Jarzabowski et al(2012), focused on the impact of feedback. They considered the impact of feedback on motivation following receipt of positive feedback from a coach. They recruited 29 coaches to undertake a 5-session coaching programme, and gave two groups positive feedback which either did or did not fit with the individual's promotion focus. The researchers found that feedback which fitted with the individual's achievement focus increased their motivation. This indicated that if the feedback matches a participant's desired outcomes, the feedback would be more likely to be effective. They suggested that further study would be useful in specific settings, to see whether alternative types of feedback would be different depending on the situation and the organisation. A major limitation of the study was that there was no group of participants in the study not receiving feedback, therefore it was difficult to see whether the impact of feedback was more than, lesser than, or equal to the impact of no feedback on motivation. Their key finding was that feedback effectiveness may be increased by framing feedback to match the individual's focus.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]This chapter highlighted a number of theories in the field of psychological research in relation to feedback and its impact on learning. We have looked at the different types of feedback and what they can achieve. The ways of delivering feedback have been explored, along with things to consider when delivering feedback, and the necessity of feedback for effective outcomes. Theory on motivation, goals, and interest was discussed, and the importance these have in helping us understand the underlying concepts of feedback on learning. Activities have been provided along the way to help the reader apply their learning to everyday situations, and reflect on their own experiences, in order to develop more of an understanding of how psychological theory and research can be applied to everyday life.

Here are some tips that can help you to make the most of feedback received:

- reflect on your motivational style, be aware what helps to motivate you and keep you motivated. Use this knowledge when you are undertaking tasks that otherwise you are not motivated to complete. Being aware of why you are motivated to achieve something is key to how successful you will be at attaining your goal;

- be interested in the task at hand. If your interest to the topic doesn't come naturally but you are required to complete it, try to identify a reason why it will be beneficial for you and you will be more likely to succeed;

- ensure you are clear about the goal or goals you are trying to achieve;

- in the learning process make sure you clarify your goals with your teacher or coach, and give them feedback about what they have said to you, this will not only help you to get the most out of your learning situation but also assist them to be a better instructor in the future.

Here are some tips that can help coaches and teachers make the most of their opportunities for feedback:

- ensure that your learner understands what the assessment/task is requiring of them, to make the most of the feedback you provide;

- your relationship with the student is very important, and if of good quality will assist the student to increase their engagement in the task at hand;

- remember the learner is in the best position to judge the feedback they receive, so seek feedback from them!

See also

[edit | edit source]- Goal setting (2013 Book chapter on Goal setting)

- Intrinsic motivation (2013 Book chapter on Intrinsic motivation)

- Workplace motivation (2013 Book chapter on Workplace motivation)

- Feedback (2011 Book chapter on Feedback)

- Wikipedia - learning styles

References

[edit | edit source]Harks, B., Rakoczy, K., Hattie, J., Besser, M., & Klieme, E. (2014). The effects of feedback on achievement, interest and self-evaluation: the role of feedback's perceived usefulness, Educational Psychology, 34(3), pp269-290

Hattie, J. (2008) Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analysis relating to achievement. Retrieved from University of Canberra E-Reserve.

Hattie, J. (2012) Know thy impact. Educational Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org

Hattie, J.A.C. & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp81-112

Hidi, S. (2006) Interest: a unique motivational variable. Educational Research Review, 1, pp69-82

Jarzebowski, A.M., Palermo, J. & van de Berg, R. (2012) When feedback is not enough: the impact of regulatory fit on motivation after positive feedback. International Coaching Psychology Review, 7(1), pp14-32.

Kluger, A.N. & DeNisi, A. (1996) The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, pp254-284.

Krapp, A. (2005) Basic needs and the development of interest and intrinsic motivational orientations. Learning and Instruction, 15, pp381-395

Krenn, B., Wurth, S., & Hergovich, A. (2013) The impact of feedback on goal setting and task performance. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 72(2), pp79-89

Locke, E.A., Shaw, K.N., Saari, L.M., & Latham, G.P. (1981) Goal setting and task performance: 1969-1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90, pp125-152

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4) 370–96.

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., & O'Donovan, B. (2010) Feedback: all that effort but what is the effect? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3) pp277-289.

Rebar, A.L. & Conroy, D.E. (2013) Experimentally manipulated achievement goal state fluctuations regulate self-conscious emotional responses to feedback. Sport, Exercise and Performance Psychology, 2(4) pp233-249.

Reeve, J. (2009) Understanding motivation and emotion (5th ed.) USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25. pp54-67

Senko, C. & Harackiewicz, J.M. (2005) Regulation of Achievement Goals: The Role of Competence feedback. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), pp320-336

Skipper, Y. & Douglas, K. (2012). Is no praise good praise? Effects of positive feedback on children's and university students' response to subsequent failures. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, pp327-339