Motivation and emotion/Book/2013/Power motivation

What is power motivation? What are the costs and benefits of power motivation?

Overview

[edit | edit source]

As a Personal Trainer, motivation is at the forefront of my business success. When considering motivation, and furthermore my motivation behind writing this self-help chapter, I instinctively think of my own competitiveness, the will to win and the way that makes me feel.

What motivates me to link my natural fascination with competitiveness and winning, to wanting to share this interest and help others to be motivated enough to achieve? Winning and competing is about power. What is power motivation? Is it the need for achievement, or is it simply a theory? Is it what motivates people just to do? Can power motivation be the fuel for success in sport, in weight loss and in life in general?

David McClelland (1976) believes that 'power truly is the great motivator'. His studies have related to positions of employment and power motivation, but the theory still applies. Power motivation is about those who are in first, or more so, how and why they strive to get in first. Whatever your 'power drug of choice', everyone has an inherent desire to feel the power of achievement. Mine just so happens to be winning. So how do we can get to the finish line first? How do we reap the rewards and enjoy our success? Power motivation may assist us in getting there. Power motivation may be the answer.

While we may consider power as an answer to motivation, getting ahead and winning, we must also gain an understanding of its concept. As humans, each individual shows distinct variances in how much they may pursue and relish the feeling of power. While some have the drive to become noticeable through greatness, taking power from standing out above all others, there will always be others that do not strive to be at the forefront of social greatness and are completely content to fly under the radar (Schultheiss, 2007). Therefore, it must be considered that those who have the natural instinct of drive and power above others who do not, perhaps have greater success in winning. If this is so, then the purpose of this chapter should be in fact, to understand the power motives of such individuals, closing the gap between them and others who do not derive much pleasure from the recognition of others.

As a self-help chapter, considerations must also be made for socialised versus personalised power motivation. While there is a strong indication that power motivation stems from social recognition, importantly here there should be a distinction of power motivation for personalised reasons. If power is truly self-serving, the motivation to win or to be successful may be based on the theory of self-serving power motivation. McClelland (1976) believes that being the best may come from within those who truly like the power to begin with, so how do we learn to love the power?

Theory of power motivation

[edit | edit source]In the early 1960s, David McClelland built on this work by identifying three motivators, following Henry Murray’s (1938) and Abraham Maslow’s (1940) work on the human theory of needs. McClelland (1987) believed that these motivators are actually learned, which is why the theory is sometimes called the “Learned Needs Theory”.

McClelland (1987) affirms that as humans we all have three motivating drivers (see Table 1), and one of these will be our dominant motivating driver. This dominant motivator is largely dependent on our culture and life experiences. The three motivators are achievement, affiliation, and power.

Table 1.

McClelland's human needs theory

| Dominant Motivator | Characteristics of this person |

|---|---|

| Achievement | Has a strong need to set and accomplish challenging goals.

Takes calculated risks to accomplish their goals. Likes to receive regular feedback on their progress and achievements. Often likes to work alone. |

| Affiliation | Wants to belong to the group.

Wants to be liked, and will often go along with whatever the rest of the group wants to do. Favors collaboration over competition. Doesn't like high risk or uncertainty. |

| Power | Wants to control and influence others.

Likes to win arguments. Enjoys competition and winning. Enjoys status and recognition. |

People will have different characteristics depending on their dominant motivator. Specifically the need for power (nPow) is a term that was explained by David McClelland in 1961. McClelland's view was influenced by the revolutionary work of Henry Murray who first identified underlying psychological human needs and motivational processes. Particularly McClelland’s nPow helps explain an individual's drive to be in the lead. Concurring with his theory there are two kinds of power motivation, social and personal (McClelland, 1987).

Reeve (2007) explains that the principle of the need for power is an aspiration to make the physical and social world adapt to one’s personal image (Winter & Stewart, 1978). People high in the need for power desire to have “impact, control, or influence over another person, group, or the world at large” (Winter, 1973). Reeve categorises the power needs into three separate desires to offer a simplified understanding of the theory behind the need for power:

- Impact allows power-needing individuals to establish power.

- Control allows power-needing individuals to maintain power.

- Influence allows power-needing individuals to expand or restore power.

Exploring power motivation and the brain

[edit | edit source]

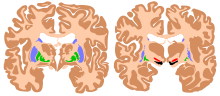

The motivational system of the brain works largely by an incentive versus penalty mechanism. When a particular behaviour is followed by positive consequences, the incentive mechanism in the brain is activated, which encourages structural changes inside the brain that cause repetition of that behaviour whenever a comparable state occurs. Equally, when a behaviour is followed by negative consequences, the brain's penalty mechanism is motivated, stimulating structural changes that cause the behaviour to be inhibited when similar situations occur.

This incentive versus penalty system is instigated by an exclusive set of brain structures, including the basil ganglia, which is a set of interrelated areas at the base of the forebrain. There is extensive evidence that the basal ganglia are the central site at which decisions are made. Incentives and penalties work by changing the association between the messages that the basal ganglia receive and the decision-signals that are produced, therefore assisting in the motivational choices we make, be it a positive or a negative one.

The role of hormones in winning

[edit | edit source]Nelson (n.d) states that research has shown that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a central role in the reinforcement of the behaviour that follows the positive consequences. Mehta & Josephs (2010) suggest that human social motivation occurs through naturally occurring testosterone and cortisol, but studies have shown that the hormones oxytocin and progesterone contribute to social motivation also.

Testosterone versus progesterone

[edit | edit source]

Testosterone[edit | edit source]Evidence has specified that gonadal steroid hormones are involved in motivational processes that are also involved with dominance, sex drive, and attachment (Schultheiss, Wirth & Stanton, 2004). In males, a need for dominance, or scientifically known as the implicit power motive, has been shown to be associated with testosterone release. The implicit power motive is an unconscious concern for having impact on others or the world at large. In a study by Schultheiss & Rohde, (2002) they demonstrate how implicit power motivation moderates men’s testosterone responses to winning or losing in a competitive environment. It was found that after winning testosterone increases, negotiating the effect of power motivation on implicit learning. What this means is that implicit power motivation plays a moderating role in testosterone responses to winning. Interestingly, they also found that there was testosterone increases in the participant who had lost in competition, which was inferred also to implicit learning. Furthermore, these increases in testosterone may have some effect on increasing levels of power motivation through the improved implicit learning. Importantly, the findings in this particular study offer some support to the ideal that this post-competition increase in testosterone may be associated with power motivation reward and reinforcement, therefore giving some hopes to individuals that are inhibited. The notion that power motivation can be derived from implicit learning through hormonal changes after competition, regardless of the outcome is certainly an interesting view. However, a realistic understanding of the direct effect of winning and losing a competition on testosterone is unclear. |

Progesterone[edit | edit source]Comparatively less is known about the role of progesterone in motivational processes. Schultheiss, Wirth & Stanton (2004) explain that high levels of progesterone show known effects of decreased sexual motivation, which also suggests a link between progesterone and affiliation motivation, or a need to have intimate, positive relationships with others and like the power motive, is part of McClelland’s Human Motivation Theory. While we now have some understanding of a correlation between testosterone and power motivation, progesterone and its link to affiliation motivation is questionable in the quest for self-help in power motivation. Unlike those with high power motive, those with affiliation motive want to belong to the group, want to be liked, and will often go along with whatever the rest of the group wants to do. Importantly, they choose collaboration over competition and err on the side of caution and certainty. Progesterone can be used in another hormonal pathway through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to self-help and power motivation. Progesterone can be released as a by-product of stress hormones and is potentially involved in the down-regulation of the stress response (Wirth, Welsh, & Schultheiss, 2005). Wirth et al. (2005) examined the possibility that implicit motives are weaknesses to specific stressors. They anticipated that certain events that are generally expected to be stressful are only stressful to the degree that they represent in difficulty. Wirth et al. state the evidence supporting this hypothesis comes from research on the effects of a social defeat on the release of cortisol, a hormonal marker of stress. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis responds to both physical and psychological stressors by increasing glucocorticoid release. Only individuals high in implicit power motivation respond to this type of event with rising levels of cortisol, whereas individuals with a weak power motive show virtually no increases of cortisol (Wirth & Schultheiss, 2006). However, these results remain uncertain as to whether progesterone is in any way beneficial in assisting with power motivation. Power motivation and the 'need' for achievement[edit | edit source]McClelland & Burnham (1976) understand those with high power motivation as having a focus on setting goals and reaching them by putting their own achievement and recognition first. Therefore in order to help the self, one must consider their own needs, goals and pursuit of achievement in order to understand and fully utilise their own power motive. Merrick & Shafi (2011) describe the different types of power as:

Five factors relating to the fear of power have also been acknowledged:

Merrick & Shafi believe these self-consciousness predispositions can moderate power by directing it into adequate social behaviour. Power motivation can be measured by incentive and probability of success. McClelland and Watson (1973) indicate that gratification of the power motive depends merely on incentive and is not motivated by the likelihood of success. Power motivated individuals select high-incentive goals, as achieving these goals gives them major control, and satisfaction in the need for achievement. Goal selection[edit | edit source] Merrick & Shafi (2011) demonstrate power motivation with regard to incentive as the inclination to seek power and inhibition of power. Tendency to seek power is lowest for low-incentive goals and highest for high-incentive goals. If we relate this to the matter of competition and winning, those who initially take the incentive to strive for high-incentive goals, also acquire the highest power. Perhaps then, those who have met and succeeded in their goal selection have a high power motive than those who have not. Reeve (2009) explains that goals are set and achieved more easily by those who have a high desire for power as opposed to those who have a low desire. He states further that with a high need for power, there is also an increase in the tendency to approach rather than to inhibit, affirming that high power motivation and action tend to go hand in hand. McClelland & Burnham (1976) observed that many of those who reach the top of professional organisations and are ranked as extremely successful in their roles and motivating others are also of concern to them. McClelland (1987) expresses these qualities as the true need for power. Furthermore power motivation is not about one with dictatorial, overbearing behaviour, rather one with a need to have some influence, to be significant and efficient in achieving goals. In other words, a person who is motivated from something internal to them, or intrinsically motivated may find the initial power motive to win. However just as motives do, goals also direct behaviour and unlike implicit motivation, goals predict behaviour when the individual cognitively decides on a course of action. This action can be motivated from either explicit or implicit power motivation. Regardless, if we consider power motivation and it’s relevance to a need for achievement, it must truly come from within as an implicit power motive. Socialised versus personalised power motivation: who wins?[edit | edit source]If we consider the "self-help" motive behind this book chapter, then it must be said that importantly here, personalised power motivation may perhaps be of greater use in conquering ones aspirations of winning. Only those who have the need for social recognition can truly be successful through socialised power motivation, however in using personalised power motivation each and every individual can benefit. So how do we distinguish the two, and use them to our benefit? Socialised power motivation[edit | edit source]An individual with socialised power motive uses power as a means to achieve their goals. This motivation is more likely to achieve success. Those with socialised power motives are:

Personalised power motivation[edit | edit source]Locke (1999) describes the individual with a high personalised power motivation as one that uses it as a means to an end or ultimate personal goal. Those with personalised power motives are:

Magee & Langner (2008) state that one can desire to have influence over others either for self-serving or other-serving reasons. They explain the personalised or self-serving power motivation is positively related to achievement of prestigious possessions, such as winning a trophy or medal. Socialised or other-serving motivation on the other hand, is positively related to valuing the self as a dependable individual.

Who wins?[edit | edit source]On evaluating the two scenarios, both power motives affect decision-making processes and choices in different types of goals and situations and having a greater understanding of the two can assist in finding the path to success and winning. Costs and benefits of power motivation[edit | edit source] To look deep within power motivation and find its cost and benefits, or 'pros and cons', this analysis may be the key to finding the self-help required to generate or increase power motivation to assist in competition and winning. Understanding the 'whys' and 'why nots' can be a positive teaching tool. There are both positive and negative aspects in regards to the need for power. Veroff & Veroff (1972) state that the costs of high power motivation occur in status groups that are concerned about their weakness, indicating a false sense of power within the self. Furthermore they believe it can lead to the averting of the power state, including self-destruction. Power motivation can also prompt conflict if it is the only motivational theme in a person's life style. In their study Veroff & Veroff (1972) were able to measure a very significant fear of weakness, one that seems to be initiated by an interruption in status or approach to goal setting. They believe this hesitation can lead to avoidant responses in some circumstances, along with costs in personal regulation on other occasions. Those who have high power motivation are driven to gain power and glory, and work aggressively to be admired rather than loved (McClelland & Watson, 1973). This can work positively when aiming to success in meeting goals. Rosenthal & Pittinsky (2006) explain the success of leaders with high power motivation; they affirm that their goals are ambitious and because they are motivated by a personal need for power, glory, and a legacy, they will acquire loyal supporters. In turn, these supporters fulfill the leaders' need for admiration, which further enhances their confidence and belief in their in their own goals, making them more successful with future aspirations. Rosenthal & Pittinsky state that for U.S. presidents, higher power motivation is related to charm, combative skill and aggressiveness; all traits that are considered relative to highly power motivated individuals. McClelland & Burnham, (1976) affirm that individuals high in power motivation are generally more concerned with influencing others than with being liked by others. However, they derive satisfaction from achieving their goals. Leaders or winners high in power motivation are not concerned with being liked; rather they are concerned with having a positive impact on others. Winners driven by power motivation are not primarily concerned with self-glory, because their self-image is not dependent on their performance (McClelland & Burnham, 1976) or their ability to dominate those around them (Rosenthal & Pittinsky). Perhaps the greatest benefit of power motivation is the maturity and security that emanates from it, keeping ones selfishness and personal growth in order (McClelland & Burnham).

Power motivation techniques: how to get yourself 'over the line first'[edit | edit source]Having gained a better understanding of the theory and concept of power motivation, it is time to look at the self and recognise where your own power motives originate and learn how to embrace them for your own personal gain. Let’s look at a self-help exercise to understand your own power motivation: It is among these reasons that you will discover your power motive and find the drive to work towards your goal. You will then be able to discern whether your desire for success is internally or externally driven. And whether it will lead to the kind of happiness you want. Sometimes, a transient happiness is all that is wanted, as a stepping-stone to other, more permanent states. Whether the happiness is derived from an external or an internal source, understanding your own power motive will assist you in achieving your own goals and in getting you ‘over the line first’! Conclusion[edit | edit source]Our own inherent desire for competition and personal need for achievement is through our self-serving power motivation. If power is truly self-serving, the motivation to win or to be successful may be come from the inner teachings of personalised power motivation and embracing the power of self-serving goal setting. This supports McClelland’s (2003) ideal that being the best may come from within those who truly enjoy the power. Notably also, power motivation can be induced socially by peers, coaches, and competitors, which is an important factor when setting goals. The need for achievement can be guided and assisted by using the “why you want to succeed’ techniques demonstrated in this chapter.

Having an understanding of the origins of your own power motivation and an awareness of both the self and other-selves power motives and their pros and cons is important, however adopting the knowledge of power motivation and applying it to the self may enlighten you on a positive path to success. |

See also

[edit | edit source]| Search for Need theory on Wikipedia. |

| Search for Need for power on Wikipedia. |

Achievement motivation 2011 book chapter

Exercise motivation 2011 book chapter

Motivation and goal setting (Book chapter, 2010)

External links

[edit | edit source]Mind tools- McClelland's human motivation theory

Businessballs.com- David C McClelland's motivational needs theory

References

[edit | edit source]Locke, E. A. (1999). The Essence of Leadership: The Four Keys to Leading Successfully. Oxford: Lexington Books.

McClelland, D. C.. (1987). Human motivation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

McClelland, D. C., & Burnham, D. H. (1976). Power Is the great motivator, Harvard Business Review. 117-126.

McClelland, D. C. & Watson, R. I. (1973). Power motivation and risk-taking behaviour. Journal of Personality, 41, 121-139.

Magee, J. C., & Langner, C. A. (2008). How personalized and socialized power motivation facilitate antisocial and prosocial decision-making. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1547-1559.

Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2010). Social Endocrinology: Hormones and social motivation. In D. Dunning (Ed.), Social Motivation. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Merrick, K. E., & Shafi, K. (2011). Achievement, affiliation and power: Motive profiles for artificial agents. Adaptive Behaviour, 19(1), 40-62.

Nelson, K. (n.d.). Motivation and the Brain: How incentives affect the brain and motivation.

Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding motivation and emotion (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rosenthal, S. A., & Pittinsky, T. L. (2006). Narcissistic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 617–633.

Schultheiss, O. C. (2007). A biobehavioral model of implicit power motivation arousal, reward and frustration. In E. Harmon-Jones & P. Winkielman (Eds.), Social neuroscience: Integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior (pp. 176-196). New York: Guilford.

Schultheiss, O. C., & Rohde, W. (2002). Implicit power motivation predicts men’s testosterone changes and implicit learning in a contest situation. Hormones and Behaviour, 41, 195–202.

Schultheiss, O. C., Wirth, M. M., & Stanton, S. J. (2004). Effects of affiliation and power motivation arousal on salivary progesterone and testosterone. Hormones and Behaviour.

Veroff, J. & Veroff, J. B. (1972). Reconsideration Of A Measure Of Power Motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 78(4), 279-291.

Winter, D. G. (1973). The power motive. New York, NY: Free Press.

Winter, D. G., & Stewart, A. J. (1978). Power motivation. In H. London & J. Exner (Eds.), Dimensions of personality. New York, NY: Wiley.

Wirth, M. M., Welsh, K., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2004). Salivary cortisol changes in humans after winning or losing a dominance contest depend on implicit power motivation. Manuscript submitted for publication.