Motivation and emotion/Book/2013/Money and happiness

The effect of money on happiness

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Have you ever found yourself to be worrying about money? Whether you’re concerned about significant issues such as rent and being able to pay the bills, or whether you’re concerned about having enough cash to buy your morning coffee, there is no denying that money whether consciously or not, centres around our day. Universally as individuals and as a community we strive to aim for happiness; to have the best outcome we can possibly attain for ourselves. Therefore is makes sense that a relationship should occur between our financial goals and issues with our emotional states and happiness. The following topics will be covered in this chapter;

- The historical background of money and happiness will be discussed in regards to comfort and royalty in the middle ages

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs will be discussed with the aim to help explain a potential theory of money in relation to happiness.

- The functions of money in a literal and psychological sense will be explained.

- The concept of materialism and the emotions connected to possessions will be explained by the notion of ‘emotional shopping’.

- The problem disorder pathological gambling will be considered and whether or not it can negatively influence our happiness by negatively influencing our finances.

- How to achieve financial goals will be deliberated using the techniques of goal setting, goal commitment, and theories such as the transtheoretical model of change.

What is happiness?

Happiness is conceived as the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of their life favourably (Veenhoven, 1990). The theory that happiness is relative derives from Greek philosophy and is applied over all psychological backgrounds (Veenhoven, 1990). This theory holds that happiness does not depend on objective good, but rather on subjective comparison (Veenhoven, 1990). Happiness is seen as both futile and evasive; futile because a happy life is not necessarily a good life, and evasive because standards tend to rise with success, leaving the individual as unhappy as before (Veenhoven, 1990). Collectively we require a welfare state to maximise material comfort, legal protection and social security in the belief that such social progress will make life more satisfying (Veenhoven, 1990).

How is money relative to happiness?

To determine how money relates to happiness we need to first discuss how researchers study and measure happiness. Argyle (2001) explains this through the difference between Subjective Well Being (SWB) and Objective Well Being (OWB). To explain briefly, SWB is a measure of happiness conducted by asking survey respondents how they felt about their life, and OWB is a measure of observable variables, such as life expectancy, that we believe are important for a good life (Argyle, 2001). In 1976 Fromm criticized industrialized societies for neglecting “being” in favour of “having”- an emphasis he believed inhibits Maslow’s self-actualization (Van Boven, 2003). Scitovsky also in 1976 suggested that people in industrialized societies, particularly the US, have created a “joyless economy” by pursuing comforts to the detriment of short-lived pleasures (Van Boven, 2003). This suggests a negative reflection on money and happiness, proposing a detrimental outlook on personal pleasures and self-actualization in favour of wealth. Frank (1999) observed that across-the-board increases in our stocks of material goods produce virtually no measurable gains in our psychological or physical well-being, It appears that bigger houses, and faster cars do not make us any happier (Van Boven, 2003). If according to this research materialistic items do not make us any happier then how come possessions have become so valuable? Tang (2007) explains that although money is used universally, the meaning of money is in the eye of the beholder and is a “frame of reference” to examine ones everyday life.

Historical background

[edit | edit source]Historically speaking money relative to happiness would make sense. In medieval times Kings and Queens were considered the epitome of wealth and power, other people who were not so fortunate had to suffer in poverty. The kings maintained their power and reign due to ownership of the land within their kingdoms (Newman, 2013). They would collect taxes from lords, barons, the clergy and the peasants through the economic means of feudal system (Newman, 2013). Ultimately the functions of money during the medieval period did not just involve coins, it involved land and trade and barter at local markets. If land and trading were capable of paying debts and buying goods then why was there a need for people to earn money in terms of coins at all? People needed to earn coins to pay the church for their sins (Newman, 2013). Money was generally earned by those who lived in the city and villages, farmers, ranchers, artisans, day labourers, retailers, all used money to exchange their products and services (Newman, 2013). Although members of nobility had the privileges and a leisure lifestyle so to speak, majority of citizens were very poor and oppressed.

The currency used in the form of metal coins came in varying qualities and weights. The most valuable coins were gold, then silver, and then copper (Chen, 1998). However currency of promise was often used in large-scale transactions (Newman, 2013). Small silver coins were the most commonly used, however wealthy people of this period also used pounds, schillings and pence (Newman, 2013). Taxes and rents however were not always paid in the form of coins. Peasants could pay the taxes or rents by either working in the manor doing various chores and by managing the land, or they could join the troops of barons (Newman, 2013). They could also offer clothes, food, and other necessities for the soldiers of the troops of baron (Newman, 2013). This implies that coins in the middle ages were not significant in political exchanges and affairs.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs

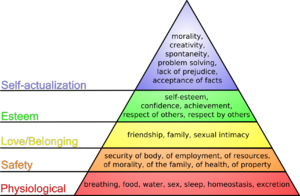

[edit | edit source]Maslow was arguably one of the most significant psychologists of modern time. Maslow advanced a general theory of human motivation which emphasized a concept of needs (Oleson, 2004). His Hierarchy of needs involves the use of motivation concepts. The first need is labelled as physiological- food and water; the second need is safety- the ability to feel secure; the third need is belongingness and love- friends, family, relationships; the fourth need is esteem- having self-confidence, and the fifth need is self-actualization- where each individual makes maximum use of his or her individual gifts and interests (Hagerty, 1998). In regards to money and happiness Maslow’s hierarchy of needs could be seen to fulfil each need through;

- Physiological; as in having the resources to buy food and to have running water,

- Safety; having the ability and the money to install security systems in the literal sense, and also having a financial security ‘peace of mind’ in the psychological sense,

- Belongingness and Love; the ability to do activities that bring relationships closer therefore making you feel more connected to others e.g. taking your partner out to dinner, taking your kids to the zoo, having friends over for a BBQ

- Esteem; money can bring a sense of self-confidence in the way you can afford to dress, the type of car you drive, the type of house you live in. Although seemingly shallow types of esteem- they are esteem nonetheless as they bring forward a sense of self-confidence.

- Self-actualization; making maximum use of your individual gifts and interests- for example if you have the resources to help others through charity work or donations, some celebrities for example have an incredible amount of wealth and therefore give back to the community.

As society evolves the concept of money becomes more and more valued. Diener (1984) suggests that money can often give a sense of security against potential misfortunes, making and having money may be sources of self-esteem in a society that highly values this resource. Maslow believed that in most humans there is an active drive towards health, growth and actualization of the human potential (Oleson, 2004). The society we live in today directs health and growth through having the potential resources to do so. Maslow characterized humans as perpetually ‘wanting creatures’, always possessing some type of unfulfilled need (Oleson, 2004). In a modernized view it can be seen that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can centre around not only psychological motivation to fulfil these needs but also having the resources and ability to do so. The human needs theory has increasingly drawn the attention of professionals in family economics and family studies. In addition, this theory was also considered by many to be relevant for the study of family financial concerns (Oleson, 2004).

Functions of money

[edit | edit source]Money permeates much of our lives and is an important element in making choices and decisions (Oleson, 2004). It is suggested that as money plays a special role in our personal and social lives, it exerts more power over us than any other single commodity (Oleson, 2004). In a literal sense the function of money is based within an economic framework. Traditionally money is used as a measure of value and a conveyor of options. However empirical studies have provided evidence to suggest that people think, feel, and act differently from each other in regard to money (Oleson, 2004). Psychologically speaking it has been reported that people who pay greater attention to extrinsic aspects of life base a higher significance on money as the major functions for them are to bring enjoyment and security and serve as a sign of achievement and success (Oleson, 2004). For individuals who value the intrinsic aspects of life money is seen as less significant and therefore cannot be used as an indicator of success (Oleson, 2004). Intrinsic and Extrinisic motivation are fundamental concepts within the field of psychology. Intrinsic motivation is obtained whenever the individual locates the causality for his activity within himself and extrinsic motivation is whenever he locates it in the external environment (Kruglanski, 1975). From an experimental background money has been used and tested as a means of incentives for participation and performance in regards to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation studies. Economists presume that experimental subjects do not work for free and work harder, more persistently, and more effectively, if they earn more money for better performance (an extrinsic outlook) (Camerer, 1999). However psychologists believe that intrinsic motivation is usually high enough to produce steady effort even in the absence of financial rewards; and although while more money might induce more effort, the effort does not always improve performance (Camerer, 1999). The effect of incentives is clearly important for experimental methodology. Various incentives can explain phenomenon’s about human thinking and behaviour which is of interest to social scientists, and may be important for judging the effects of incentives in naturally-occurring settings (Camerer, 1999)

Are emotions linked to material possessions?

[edit | edit source]Belk’s definition of materialism is the tendency to view worldly possessions as important sources of satisfaction in life (Richins, 1987). Growing interest in the association between money and happiness and the possibility that certain kinds of spending may be more closely linked to happiness than other kinds have led researchers to ask what kinds of spending are most likely to promote happiness (Reis, 2013). Research has also suggested however that even after money has been spent, satisfaction with material things, compared with experiences is more likely to be undermined by considering the options that were not purchased and by regretting how much money was spent and on what (Reis, 2013). Consistent with these ideas, prior research demonstrates that materialistic people tend to report lower subjective well-being than non-materialistic people (Van Boven, 2003). People who strongly agree with such statements as “Some of the most important achievements in life include acquiring material possessions” and “Buying things gives me a lot of pleasure” report lower levels of satisfaction with life than people who disagree with such statements (Van Boven, 2003). It is also generally found that people who endorse such extrinsic aspirations such as “you will buy things just because you want them” report lower levels of well-being (Van Boven, 2003). Tang (2007) discovered that materialism is negatively correlated with life satisfaction, subjective well-being, and general affect; he also wrote that as societies grow wealthy, differences in well-being are less frequently due to income and are more frequently due to social relationships and enjoyment at work. People with a high level of subjective well-being are satisfied with marriage, work, health, finances, and friendship, and are associated with frequent positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and a global sense of satisfaction with life (Tang, 2007). Those with money can afford fun and pleasurable activities to a much greater extent (Diener, 1984). Those with money are more likely to be able to avoid negative events and persons, and often give people a sense of security against possible misfortunes (Diener, 1984). Making and having money may be a source of self-esteem in a society that highly values this resource (Diener, 1984).

Media's Portrayal of Money and Happiness

Although people such as celebrities and socialites who are wealthy suggest a form of unattainable happiness to the ‘average Joe’ as such, research has suggested that money cannot buy you happiness. If that is the case then why are the majority of us enviable of this certain lifestyle? Perhaps it has something to do with the images we are presented with daily through media outlets. Within the consumer culture the idea is that goods are a means to happiness (Richins, 1987). Satisfaction within life is not achieved by religious contemplation, or social interaction, or a simple life, but by possessions and interaction with goods (Richins, 1987). The cultivation hypothesis suggests that media to some extent shape or cultivate people's perceptions of social reality (Richins, 1987). This is especially true when media images are not entirely congruent with the typical environment of viewers or when viewers do not have alternative sources of information on which to base their judgement of social reality (Richins, 1987). The frequent pairing of products with happy consumers in television and other advertising may result in an unexplained belief that possessions bring happiness (Richins, 1987).

Emotional Shopping

Emotional shopping or better known as retail therapy is an emotional process thought to be driven by negative moods (Dawson, 1990). The comfort of buying new objects is seen to be a way of feeling good about oneself and one’s life. However research has suggested that emotional shopping is actually more relative to positive moods and the motivational outcomes that affect these moods. Motives are suggested to drive the behaviour that brings consumers into the marketplace, but the emotions that are experienced in the marketplace affect the consumer’s preference and choice (Dawson, 1990). Multiple theories exist surrounding the shopping motivation phenomenon; however no one theory has yet to dominate this area. The variety of these theories are summarised and framed by the motivational typology described by Westbrook and Black (1985), they suggest that shopping motivation falls into three categories; product-oriented, experiential, and a combination of the two (Dawson, 1990). Product-oriented conceptualises the need to buy something such as a birthday present or an anniversary gift (Dawson, 1990). The experiential notion discusses a hedonic or recreational aspect such as the pleasure of visiting the shopping centre itself, and the combination of the two occurs when the individual seeks to satisfy the purchase need as well as having a pleasurable recreational experience (Dawson, 1990). The emotions and moods of which a consumer has are considered to be situational variables that affect his or her proclivity to buy (Dawson, 1990). However variability of emotional states in the shopping centre are magnified by the strength of the motives that instigated the behaviour (Dawson, 1990). A study conducted by Donovan and Rossiter (1982) examined the effects of the emotions pleasure and arousal on a number of retail outcomes (Dawson, 1990). They discovered that pleasure resulting from the exposure to store atmosphere influenced such retail behaviours as spending levels, amount of time spent in the store, and willingness to return (Dawson, 1990). Other researchers have found that mood is positively related to measures of store image, number of products bought, and spending levels above what consumers had planned, and it was uncovered by Weinberg and Bottwald (1982) that impulse buyers have a greater emotional activation than non-impulse buyers (Dawson, 1990).

Gambling and happiness

[edit | edit source]

Pathological gambling (PG) is a persistent and recurrent maladaptive pattern of gambling behaviour characterized by increased preoccupation with gambling activities, loss of control, and continued gambling despite problems in social or occupational functioning (Vizcaino, 2013). Within the study of addiction, attentional bias refers to the observation that substance-related cues tend to capture the attention of experienced substance users (Vizcaino, 2013). The lifetime prevalence of pathological gambling is 1% to 3% and is associated with negative situations such as significant financial losses, legal problems, disrupted interpersonal and familial relationships, and increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders, suicide attempts, and several medical conditions (Vizcaino, 2013). Individuals who meet some but not all of the criteria for pathological gambling are considered a problem gambler which is a condition that affects and additional 1.3% to 3.6% of the population and is also associated with substantial individual suffering and societal burden (Vizcaino, 2013). Because pathological gambling and problem gambling have similar phenomenology, patterns of comorbidity, treatment response, and genetic vulnerability with substance use disorders, they are often considered behavioural addictions (Vizcaino, 2013).

The attentional bias concept is based on Robinson and Berridge’s incentive-sensitization theory, which suggests that the substance and its associated cues increase their motivational incentive and salience with each new administration (Vizcaino, 2013). This theory suggests that through classical conditioning, those cues capture the individual’s attention, are desired, and lead to drug-seeking behaviour and relapse (Vizcaino, 2013). Therefore, according to the incentive-sensitization theory, attentional bias may contribute to the relapse of PG in three interrelated ways (Vizcaino, 2013). First continued engagement in gambling activities among pathological gamblers could be because of an enhanced likelihood to detect gambling related cues in the environment, which may trigger relapse through conditioned responses (Vizcaino, 2013). Second once a gambling related cue is detected it may be automatically processed making it difficult to deviate attention away from it, which may also increase the risk for relapse, and thirdly because attentional capacity is a limited resource direction attention to one stimulus suppresses the process of competing cues, leaving no attentional resources for alternative cues (Vizcaino, 2013).

Theories of gambling have long implied that mood plays a role in gambling behaviour. Griffiths (1995) found that regular and pathological gamblers were more likely than non-regular gamblers to report negative affect before gambling, both negative and positive affect during gambling, and negative affect after gambling (Goldstein, 2013). This research indicates that gambling serves as an important mood-altering function, with individuals gambling to achieve negative alleviation, positive affect enhancement, and social reward (Goldstein, 2013). Basically literature suggests that individuals gamble despite the repercussions because they are aiming to alleviate a negative mood they may be in, they hope to enhance a positive mood and gain social rewards.

How to achieve financial goals

[edit | edit source]Being financially secure is a view that almost everyone considers to be significant within their life. The ability to provide for one’s self and one’s family's basic needs on top of material possessions is a desired outcome relative to modern society. Having the capability to become financially secure is based around the idea of goal setting. Goals can be defined as mental representations of desired outcomes to which people are committed (Mann, 2013). Setting a goal creates a sense of urgency which therefore motivates individuals to make an effort to reduce the discrepancy between their current state and their desired state (Mann, 2013). However commitment to a goal is different to a goal intention. Goal intentions specify a desired end state, whereas goal commitment indicates how much that end state is desired and in return motivates action (Mann. 2013).

Theories involving creating financial goals do not generally rest on normative goal setting guidelines. Within the personal finance profession the most commonly used theory is the life cycle theory of consumption (Lyons, 2008). It is a positive theory which predicts that individuals make consumption and savings decisions based on their life expectancy and expected life income (Lyons 2008). Although the life cycle theory of consumption is stated to be the most commonly used theory, a growing body of literature focuses on looking at the process of changing financial behaviour within the context of the transtheoretical model of change. Based on the work of Prochaska (1979) and Prochaska and DiClemente (1983), this model integrates major psychological theories into a theory of health behaviour change (Lyons, 2008). According to the transtheoretical model of change, behaviour change involves progressing through a series of stages, with individuals commonly relapsing before successfully giving up negative behaviours or engaging in positive behaviours (Lyons, 2008). As said above this theory is commonly used for health behaviour change, however from a financial outlook this theory can look at the process of changing negative or unnecessary financial and spending behaviours.

Example 1[edit | edit source]John is a man who regularly places bets of higher and higher value and suffers incredible losses each time. Due to his unbelieveable debt and financial loss, he decides he could potentially benefit from the transtheoretical model of change with the help of a psychologist by proceeding through the necessary psychological stages and successfully giving up the negative behaviour associated with gambling. |

Summary

[edit | edit source]

Although the common misconception is that money does indeed make you happy, research suggests that other factors such as family and peer relationships, and having a greater subjective well-being are increasingly more significant. Historically speaking money came in many forms, not only through coins but through trade and barter as well. Maslow's hierarchy of needs explains a theory of motivation to 'be the best we can be' however this theory can also be applied to financial situations and how having money helps you 'be the best you can be'. Every individual wants to feel secure in their life, whether that security comes from money or not depends entirely on them. However there is no question that money permeates most of our lives. To be able to function not only as an individual but also as a society money is considered a valuable concept. Materialism determines the amount of possessions we feel we need, research has shown that emotions linked to materialism are generally negative and individuals who value material possessions have a lower life satisfaction. Money however can also have a negative effect on serious psychological disorders; such as pathological gambling. The addiction to gambling can significantly ruin someone's life, and affects people of all ages. Money is such a valued part of modern society, yet so many people suffer because of the relationship they have with it. Happiness can be seen to be held in the eye of the beholder, whether that includes being financially secure is totally dependent on an individual's preference. The ability to see money as an aspect of one's life and not the centre of it can reduce the feelings of anxiety and negative affect that research suggests. Learning ways to set goals, and commit to those goals can greatly influence financial outcomes. Universally everyone suffers with money and happiness in their own way, some people may be happy with $50, whereas others may not be happy with $50 million. The ways we set out to deal with our relationship between money and happiness is what sets us apart from everyone else. Finding a balance between what you want and what you need in life, and opening yourself up to a greater subjective well-being can change your outlook from negative to positive.

See also

[edit | edit source]- Failure and happiness (Book chapter, 2021)

- Materialism and psychological well-being (Book chapter, 2021)

References

[edit | edit source]Camerer, C. F., & Hogarth, R. M. (1999). The Effects of Financial Incentives in Experiments: A Review and Capital-Labor-Production Framework. Journal of Risk & Uncertainty, 19(3), 7-42. Retrieved From http://zh9bf5sp6t.scholar.serialssolutions.com/?sid=google&auinit=CF&aulast=Camerer&atitle=The+effects+of+financial+incentives+in+experiments:+A+review+and+capital-labor- production+framework&id=doi:10.1023/A:1007850605129&title=Journal+of+risk+and+uncertainty&volume=19&issue=1-3&date=1999&spage=7&issn=0895-5646

Chen, D. Money and Trading. (1998). Retrieved from the Medieval Economy website: http://web.nickshanks.com/history/medieval/trading

Dawson, S., Bloch, P. H., Ridgway, N. M. (1990). Shopping Motives, Emotional States, and Retail Outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 66(4), 408-420. Retrieved from http://zh9bf5sp6t.scholar.serialssolutions.com/sid=google&auinit=S&aulast=Dawson&atitle=Shopping+motives,+emotional+states,+and+retail+outcomes&title=Journal+of+retailing&volume=66&issue=4&date=1990&spage=408&issn=0022-4359

Diener, E., Horwitz, J., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). Happiness of the very Wealthy. Social Indicators Research, 16, 263-274. doi: 0303-8300/85.10.

Goldstein, A. L., Stewart, S. H., Hoaken, P. N. S., & Flett, G. L. (2013). Mood, Motives, and Gambling in Young Adults: An Examination of Within- and Between- Person Variations Using Experience Sampling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours. Advance Online Publication. Doi: 10.1037/a0033001.

Kruglanski, A. W., Riter, A., Amitai, A., Margolin, B. S., Shabtai, L., & Zaksh, D. (1975). Can money enhance intrinsic motivation? A test of the content-consequence hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31(4), 744-750. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.31..4.744.

Lyons, A. C., Neelakantan, U. (2008). Potential and Pitfalls of Applying Theory to the Practice of Financial Education. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 42(1), 106-112. Retrieved From http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy1.canberra.edu.au/ehost/detail?vid=8&sid=3b7772fd-16ca-40fa-a018-760c1eb9696f%40sessionmgr4&hid=28&bdata=#db=ecn&AN=0963143

Newman, S. Money in the Middle Ages. (2013). Retrieved from The Finer Times website: http://www.thefinertimes.com/Middle-Ages/money-in-the-middle-ages.html

Oleson, M. (2004). Exploring the Relationship between money attitudes and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 28(1), 83-92. Doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2004.00338.x.

Reis, H. T., Caprariello, P. A. (2013). To do, to have, or to share? Valuing experiences over material possessions depends on the involvement of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 199-215. Doi: 10.1037/a0030953.

Richins, M. (1987). Media, Materialism, and Human Happiness. Advances in Consumer Research, 14(1), 352-356. Retrieved from http://zh9bf5sp6t.scholar.serialssolutions.com/sid=google&auinit=ML&aulast=Richins&atitle=Media,+materialism,+and+human+happiness&title=Advances+in+consumer+research&volume=14&issue=1&date=1987&spage=352&issn=0098-9258

Tang, T. (2007). Income and Quality of Life: Does the Love of Money Make a Difference?. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(4), 375-393. Doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9176-4.

Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To Do or to Have? That is the Question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193-1202. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1193

Veenhoven, R. (1990). Is Happiness Relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1-34. Doi: 10.1007/BF00292648.

Vizcaino, E. J. V., Fernandez-Navarro, P., Blanco, C., Ponce, G., Navio, M., Moratti, S., & Rubio, G. (2013). Maintenance of attention and pathological gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 27(3), 861-867. Doi: 10.1037/a0032656.