Motivation and emotion/Book/2010/Dementia and motivation

| This page is part of the Motivation and emotion textbook. See also: Guidelines. |

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Have you ever found it difficult to find the right word to explain what you are trying to say? You can feel it sitting on the tip of your tongue, but you can't quite get it out. How about forgetting a name, or that you were meant to go to the hair dressers yesterday? Most people, I imagine, would agree that these are things that happen to them on occasion. They probably aren't distressing and you generally wouldn't think twice beyond wondering why you have been so absent minded lately.

For those who tend towards forgetfulness on a more frequent basis, you may find yourself saying several times a day, "Where are my keys?" or asking someone around you, "Have you seen my phone?". This is often followed by ".. Oh! There it is!"

But have you ever picked up your keys and stared at them in bewilderment as you try to remember what on earth these strange things are used for?

How about climbing into the driver's side of the car after 40 years of driving to suddenly have no idea what to do?

These are examples of where the early symptoms for dementia start to become seriously debilitating for those who are affected by it.

This chapter discusses:

- What is dementia?

- The causes of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease and Korsakoff's Syndrome

- Is there a treatment for dementia?

- Motivational aspects of dementia

- Why do they wander?

- Dementia and depression

What is dementia?

[edit | edit source]The root of the word ‘dementia’ comes from the Latin words de, which means ‘apart’ and mentis, which means ‘mind’. It is defined as the progressive deterioration in cognitive functioning, or a gradual loss of the ability to process thought (Nordqvist, 2009).

Dementia is a highly disabling neurodegenerative disease, and its growing prevalence in Australia is of particular concern. In the 46 years between 1995 and 2041, Australia’s population is forecast to see an increase in population of just less than 39%. In the same period of time, the population of Australians suffering dementia are projected to increase from 130,000 to 460,000 (Jorm, 2001).

To put this into perspective, this means that for a university student who is 24-years-old in 2010, there will be an increase of 253% in dementia cases by the time they reach the age of 70.

|

Symptoms of Dementia

Note. Table created from information provided by E-Medicine Health (eMedicineHealth, 2010). | |||||||||

The causes of dementia

[edit | edit source]

The term 'dementia' does not refer to one specific disease, it is the name for symptoms caused by a number of disorders affecting the brain. There are over one hundred possible illnesses that can cause dementia and a person who is diagnosed with dementia could have one or more of these disorders.

At the current time there does not appear to be strong evidence to show that dementia is an inherited disease, as the incidence appears to be random rather than passed down through family lines. There has, however, been one rare form of Alzheimer’s that has been established to have a genetic link (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002).

Alzheimer's Disease

[edit | edit source]Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and is a progressive and irreversible disease (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002). Throughout the course of the disease, which usually spans anywhere from 2 to 20 years, nerve cells and the synapses connecting them slowly degenerate and die, causing a gradual decline in memory and the ability to think and reason (Synder, 2000). During the onset of Alzheimer’s disease personality changes are common as is a decline in the ability to move or swallow, a loss in language skills and ability to communicate, and a failure to recognise and identify objects or people (Adams, 2008).

In the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease, tasks such as walking and using the bathroom become increasingly difficult and memory declines further, with many patients reaching a point where they are unable to recognise close friends and family.

Alzheimer’s disease accounts for approximately 50% of all cases of dementia and is very common in the elderly population, occurring in 1 out of every 5 people over 80 years of age (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002).

Vascular Dementia

[edit | edit source]After Alzheimer’s disease, Vascular dementia is the second most common form of dementia, accounting for approximately 20% of all cases (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002).

Vascular dementia can be caused by either a single stroke, in which case it is called a ‘single-infarct dementia’, but it is more commonly caused by ‘multi-infarct dementia’, a series of small strokes which interrupt the blood flow to the brain (Adams, 2008).

Damage generally occurs in the language and speech sections of the brain, but the damage can be more widespread and cause symptoms similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease. Like Alzheimer’s disease, Vascular dementia is not reversible and it currently has no known cure.

Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia can occur together as a “mixed dementia”, and they do so in approximately 25% of all dementia cases (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002).

Parkinson’s disease

[edit | edit source]Parkinson’s disease is also a progressive disease, consisting of shaking, tremors, difficulty in moving limbs and joints, and difficulty speaking. Some patients develop dementia in the late stages of Parkinson’s disease (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002).

Korsakoff’s syndrome

[edit | edit source]Possibly the most preventable cause of dementia is Korsakoff’s syndrome, which is caused by the consumption of large quantities of alcohol over an extended period. The risk of developing Korsakoff’s syndrome is further increased if the alcohol consumption is combined with poor nutrition, falling unconscious, and frequent falling, as this causes irreversible brain damage. Like other causes of dementia, Korsakoff’s syndrome sees a decline in memory and cognition, particularly in skills such as planning and organisation, and in social skills and balance. If the intake of alcohol is stopped, there may be a slight increase in these skills, but generally the damage is permanent (Department of Health and Ageing, 2002).

Lewy body disease

[edit | edit source]Dementia with lewy bodies is another of the main causes of dementia and may be responsible for between 10 % and 15% of all dementia cases. Lewy bodies are small deposits of protein in the nerve cells which interrupt the normal functioning of the brain. There are a number of similarities between dementia with lewy bodies and both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Like Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with lewy bodies shows a decline in memory, spatial orientation and ability to communicate. Difficulty moving, stiffness in muscles, and tremors are symptoms that are similar to those in Parkinson’s disease. As well as this, those with lewy body disease are likely to suffer from faintness, hallucinations, and sleeping difficulties (Adams, 2008).

Other causes of dementia

[edit | edit source]Other causes of dementia include:

- AIDS

- Huntington’s disease

- Pick’s disease

- Fronto-temporal dementias

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Treatment of dementia

[edit | edit source]

Most of the diseases that cause dementia are irreversible and incurable, although in some situations the individual symptoms can be treated and the progression of the disease may be slowed. People with Korsakoff’s syndrome may experience a slight improvement if the consumption of alcohol is discontinued.

Similarly, we will go on to discuss the combination of depression and dementia and how treating the depression may lead to a dramatic improvement in the quality of life for the person with dementia. It would not, however, improve the symptoms of the dementia itself.

As far as treating the symptoms of dementia, there are a few therapies that are used in an attempt to improve the patients’ quality of life and slow down the progression of the disease.

Reality Orientation (RO)

[edit | edit source]This technique uses constant reminders about the individuals’ surroundings and environment to keep the person oriented. The use of aids and prompts is important (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2010) and involves using verbal and written reminders of the time, day of the week, and the names of people and objects (Larkin, 1994). A tool commonly used in this treatment is a memory board, or a reality-orientation board. It can be a blackboard or whiteboard and is used by both the carer and the patient to fill in information about schedules, the weather, to-do lists and other day-to-day information.

Validation Therapy

[edit | edit source]This method focuses strongly on accepting the reality of the person with dementia and working beside them, where they are at (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2010).

In using validation therapy, the carer doesn’t try to force reality on the person with dementia, but they also don’t completely leave them in their own world. Instead, this therapy takes a middle ground of concentrating on the feelings that arise and talking about emotions (Guide, 2010). For example, if a person with dementia were to tell you about their husband not coming to visit them, when you know that he actually passed away several years ago, rather than sternly telling them, “Now, now, you know that Bob died 12 years ago” or going along with them completely, you might talk with them about how they feel being apart from Bob, and their emotions in missing him.

Reminiscence Therapy

[edit | edit source]Using reminiscence therapy is aimed at assisting those with dementia to relive a small part of their lives and to trigger their memory through the use of smell, touch, sound, or photographs. It encourages the active sharing of their story with others, and aims to build self-esteem and a sense of their past and their current life having a purpose and worth (The Benevolent Society, 2005).

A valuable tool in reminiscence therapy can be a memory box, which is filled with items from the person’s past such as a thimble for someone who used to be a seamstress, or sandpaper for someone who used to be a carpenter.

Bea's perspective

[edit | edit source]

Bea started having problems with her memory at age 72, and was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease about three years before this interview.

One day I was driving into town to get my hair done. I was supposed to make a left-hand turn but instead, I went straight ahead into oncoming traffic. A policeman pulled me over, and I told him that I didn’t know why I did it. I’d driven this same route all along and never had any problems. It was so strange. It was terribly scary. I could have really hurt someone. That was the first time I knew there was something wrong. I haven’t driven again since then.

One of the worst things I have to do is put on my pants in the morning. This morning I kept thinking there is something wrong because my pants just didn’t feel right. I had put them on wrong. I sometimes will have to put them on and take them off half a dozen times or more. I think I’m putting them on opposite to the way they’re supposed to go on. It’s so frustrating because I look at them and try to figure it out. I think I know the way to do it and then I put them on and it’s wrong again.

I used to do a lot of entertaining, and I’d take pride in setting a nice table. But now I don’t even know on which side the fork or knife is supposed to go. I’ll get the plates on and then I’ll get the silverware. I’ll ask Joe, “Where do these go?” He’ll show me, but then I don’t remember the next time. That’s frustrating. Sometimes he must think I’m awfully stupid. I feel so dumb when I ask, “Where is my fork?” He’ll answer, “It’s right there.”

Sometimes what I’m looking for will be lying right in front of me and I won’t see it. I don’t always misplace things; they’re right there, but I just don’t recognise them. That’s a real problem. Money is getting to be terrible. I just don’t want to handle money anymore because I can’t identify it. I can trust my beautician not to cheat me. But when we go anywhere else, Joe has to do all the buying because I just don’t have the ability to work it out anymore.

I don’t like to make mistakes. I get aggravated with myself and I can cry a lot easier than I can laugh. I’d like to be perfect. But I never have been and never will be. This disease makes you feel so helpless. I’ve lost my feeling of self-satisfaction that I was capable of doing things and I resent it a little bit.

Adapted from Snyder, 2000, pp. 17-26

Motivational aspects

[edit | edit source]

In some cases of dementia, the progress of the disease sees the person losing interest in things they used to enjoy, such as hobbies or activities.

They may spend time sitting and not interacting with anything around them, either disinterested or unaware of their surroundings, or have violent mood swings where they lash out with anger for no apparent reason (Cohen & Weisman, 1991).

One possible reason for this is that the underlying motivational drives may still exist, but the person may have deteriorated beyond being able to fulfill the needs that arise from these drives. They may also feel the drive and not remember how to meet its demands, or not remember what they wanted long enough to complete the task.

Despite losing a large amount of their memory, and many abilities and skills, it is important to remember that the emotional side of the person that experiences and feels things may still be present (Adams, 2008). Either one of these - the presence of feelings that aren’t able to be communicated or drives that aren’t able to be met - could be an explanation for activities such as wandering, crying and screaming, and other behaviour that may be displayed by people with dementia.

Confused motivations: Why do they wander?

[edit | edit source]Many people with dementia will display behaviours such as wandering or pacing. When they wander away from home, this can be dangerous as they may not be able to recall the way home, and may become confused and disoriented.

An excellent short film on dementia is "Going Home" (Bay & Leng, 2009), which illustrates the fear and confusion that people with dementia face when they become lost.

It is important with behaviours like wandering to not assume that it is “just a symptom”, but to remember that there could be some underlying motivation that cannot be communicated or properly acted upon. For example, a disruption in the persons’ routine or environment could be causing anxiety that is displayed through pacing, or a look at their life history could show that they spent 50 years at the same employment and would leave the house for work at 7am every morning (Veterans’ Affairs, 1995). Repeating behaviour from their past life may simply be a habit, but they could be mentally living in back at the time when their need or drive to earn money and support a family motivated them to leave for work every morning, and their current wandering behaviour could be reflecting their confusion.

Crying, screaming, and moaning: Something isn't right

[edit | edit source]

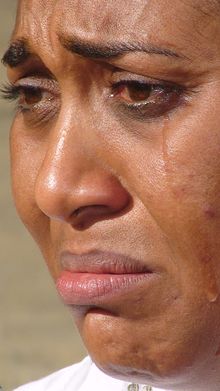

Photo by Taremu

The same could be said for behaviours such as crying, screaming, or moaning. Much like a child will cry when hungry, thirsty, wet, frightened, or for a variety of other reasons, a person with dementia may not have another way of communicating their discomfort or need for assistance. Something as simple as checking the temper

Eating: Too much or too little

[edit | edit source]Another area where motivation is affected by dementia is in the biological need to eat.

Some people with dementia think they have already eaten when meal times come, and will refuse food (see the Chapter on Dieting), risking malnutrition; while others will forget that they have eaten, and will overeat, often leading to obesity (Hoffman & Platt, 1991). This is an interesting issue, because despite most of these individuals most likely having spent their lifetimes eating in a normal and reasonably healthy way, and responding to the biological triggers that cause hunger, the loss of memory can cause the cognitive side (even though it is malfunctioning) to override the biological need and cause a kind of unconscious eating disorder.

Forgetting the addiction: The easiest way to quit

[edit | edit source]An interesting effect of dementia is that it seems to allow people to give up their nicotine addiction and smoking habit. Many people with dementia will forget that they smoke and will simply stop, without even having to try. Some research has found that the effects of changes in the brain caused by Alzheimer’s disease actually reduce the craving for nicotine (Hoffman & Platt, 1991). Families of dementia patients can sometimes remove all evidence of smoking from their houses and have the family member with dementia never notice or ask for another cigarette.

Sex and dementia: "You look like my husband!"

[edit | edit source]The need to be touched and have some level of intimacy with others is a basic human need and can be fulfilled appropriately with different people in a variety of ways.

Dementia can have interesting effects on the way that people seek intimacy and physical touch. Some people with dementia experience an increased interest in sex following the onset of the disease, while in others the interest in sex diminishes all together.

The loss of memory that comes from having dementia can cause problems when physical drives for sex arise, with some people with dementia forgetting that they are married and making advances towards people other than their partner, or by making these advances towards a stranger who looks similar to a deceased spouse.

Dementia and depression: Excess disability

[edit | edit source]Depression is also an important aspect of motivation that must be considered when looking at dementia. Approximately half of those with dementia also have minor depressive disorder, and a further 15% are estimated to have major depressive disorder (Onega, 2006). As will be discussed in the next chapter, depression has a significant impact on motivation, and when coupled with dementia this impact is even greater. In older adults, depression is likely to include symptoms such as agitation, hypochondriasis, loneliness and feelings of isolation, difficulty sleeping, an increase or decrease in appetite, and suicidal thoughts (Onega, 2006). In these ways, dementia and depression can present in a very similar way and it can sometimes be challenging to decipher whether symptoms are the result of dementia or depression. One of the easiest ways to establish whether someone is more likely to be suffering from depression or dementia is to watch them throughout the day.

People with dementia will generally wake up at their best and function at their highest level in the early morning, slowly deteriorating throughout the day. Those suffering from depression, on the other hand, show very low drive in the morning and generally begin the day confused and unhappy, with their mood and abilities improving through the day, and at its peak during the evening (Kitwood, 1997).

Depression is especially common in the early stages of dementia, as the person is generally very aware of the changes that they are going through and, especially upon being diagnosed with dementia, realise that they are slowly losing who they are (Hoffman & Platt, 1991). In a way, the progression of the disease can be a mixed blessing as memory loss becomes worse and the person is no longer aware of what they have lost.

The combination of two diseases or disorders such as dementia and depression is called “excess disability” and it means that the person with the disease will deteriorate at a more rapid rate than is usual for that disease (Hoffman & Platt, 1991). As well as declining more quickly, behavioural changes tend to be more extreme than usual. In dementia cases, when excess disability is caused by the presence of depression, the person may cry, moan, or scream more often, be more inclined to wander, less inclined to participate in activities, and may eat either very little or excessive amounts (Hoffman & Platt, 1991).

One of the positive sides to this is that unlike dementia, many forms of depression are treatable and can be cured. With treatment, the symptoms caused by depression can be alleviated and the general well-being and quality of life of the person with dementia may be increased dramatically.

Summary

[edit | edit source]Dementia is a highly disabling and degenerative disease which is growing in prevalence worldwide.

The most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer's disease, in which nerve cells and their connecting synapses degenerate and die, causing brain damage. There are over one hundred other causes of dementia, including vascular dementia, Parkinson's disease, and Lewy body disease.

Dementia does not have a cure and cannot be reversed, although some treatments do appear to slow the decline in abilities and memory of the person with dementia. The most popular technique is reality orientation, which uses prompts to remind the person of the day, time, and the names of objects and people.

Symptoms such as wandering, crying, and screaming may be as a result of experiencing motivational drives that the person with dementia cannot communicate or has lost the ability to know how to fulfill. Wandering can in some cases be due to a change in environment, and the anxiety that may come with this, or could be from a life-long pattern and the loss of short-term memory.

Depression and dementia have a high rate of correlation, with approximately 65% of people with dementia also having some form of depressive disorder. Depression in dementia patients generally makes the symptoms of dementia worse than they would normally be at that stage of the disease progression, and treating the depression can significantly improve the quality of life for the individual.

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]Allison-Bolger, V. Y., & Ramsay, R. L. (2009). Changing minds: Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Nordqvist, C. (2009). What is dementia? What causes dementia? Symptoms of dementia. Medical News Today. Retrieved November 1, 2010, from http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/142214.php

Jorm, A. (2001). Dementia: a major health problem for Australia. Position Paper 1. Retrieved November 2, 2010, from http://web.archive.org/web/20041226141206/http://www.alzheimers.org.au/upload/pp1jorm.pdf

eMedicineHealth (2010). Dementia overview. Retrieved November 4, 2010, from http://www.emedicinehealth.com/dementia_overview/page3_em.htm

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing (2002). The Carer Experience: An essential guide for carers of people with dementia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Snyder, L. (2000). Speaking our minds: Personal reflections from individuals with Alzheimer's. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Adams, T. (2008). "People's experience of having dementia." In Dementia care nursing: Promoting well-being in people with dementia and their families, edited by T. Adams, 42-65. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Larkin, M. (1994). Reality Orientation. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, from http://www.zarcrom.com/users/alzheimers/t-02.html

Alzheimer's Australia (2010). Improving quality of life. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, from http://www.alzheimers.org.au/content.cfm?infopageid=3691

Guide, G. (2010). How to talk to an elder with dementia using validation therapy, redirection & other techniques. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, from http://www.caring.com/articles/validation-therapy-and-redirection-for-dementia

The Benevolent Society (2005). Reminiscing manual version 1. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, from http://web.archive.org/web/20070227114536/http://www.bensoc.org.au/uploads/documents/reminiscing-handbook-jan2006.pdf

Cohen, U., & Weisman, G. D. (1991). Holding onto home: Designing environments for people with dementia Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Commonwealth Department of Veterans' Affairs (1995). Dementia: A practical guide for carers Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Hoffman, S. B., & Platt, C. A. (1991). Comforting the confused: Strategies for managing dementia New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Onega, L. L. (2006). Assessment of psychoemotional and behavioural status in patients with dementia. Alzheimer's Disease: Nursing Clinics of North America, 41, 23-42.

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press.