Electric Mobility/Engineering/Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from Greek ἀήρ aer (air) + δυναμική (dynamics), is a branch of Fluid dynamics concerned with studying the motion of air, particularly when it interacts with a solid object, such as an airplane wing. Aerodynamics is a sub-field of fluid dynamics and gas dynamics, and many aspects of aerodynamics theory are common to these fields. The term aerodynamics is often used synonymously with gas dynamics, with the difference being that "gas dynamics" applies to the study of the motion of all gases, not limited to air.

Formal aerodynamics study in the modern sense began in the eighteenth century, although observations of fundamental concepts such as aerodynamic drag have been recorded much earlier. Most of the early efforts in aerodynamics worked towards achieving heavier-than-air flight, which was first demonstrated by Wilbur and Orville Wright in 1903. Since then, the use of aerodynamics through mathematical analysis, empirical approximations, wind tunnel experimentation, and computer simulations has formed the scientific basis for ongoing developments in heavier-than-air flight and a number of other technologies. Recent work in aerodynamics has focused on issues related to compressible flow, turbulence, and boundary layers, and has become increasingly computational in nature.

Learning Task

[edit | edit source]- Explain why analysis of aerodynamic is important for electric mobility to extend the range of vehicles (see battery)

History

[edit | edit source]Modern aerodynamics only dates back to the seventeenth century, but aerodynamic forces have been harnessed by humans for thousands of years in sailboats and windmills,[1] and images and stories of flight appear throughout recorded history,[2] such as the Ancient Greek legend of Icarus and Daedalus.[3] Fundamental concepts of continuum, drag, and pressure gradients, appear in the work of Aristotle and Archimedes.[4]

In 1726, Sir Isaac Newton became the first person to develop a theory of air resistance,[5] making him one of the first aerodynamicists. Dutch-Swiss mathematician Daniel Bernoulli followed in 1738 with Hydrodynamica, in which he described a fundamental relationship between pressure, density, and flow velocity for incompressible flow known today as Bernoulli's principle, which provides one method for calculating aerodynamic lift.[6] In 1757, Leonhard Euler published the more general Euler equations, which could be applied to both compressible and incompressible flows. The Euler equations were extended to incorporate the effects of viscosity in the first half of the 1800s, resulting in the Navier-Stokes equations.[7][8] The Navier-Stokes equations are the most general governing equations of fluid flow and are difficult to solve.

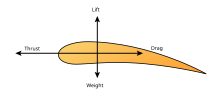

In 1799, Sir George Cayley became the first person to identify the four aerodynamic forces of flight (weight, lift, drag, and thrust), as well as the relationships between them,[9][10] outlining the work towards achieving heavier-than-air flight for the next century. In 1871, Francis Herbert Wenham constructed the first wind tunnel, allowing precise measurements of aerodynamic forces. Drag theories were developed by Jean le Rond d'Alembert,[11] Gustav Kirchhoff,[12] and Lord Rayleigh.[13] In 1889, Charles Renard, a French aeronautical engineer, became the first person to reasonably predict the power needed for sustained flight.[14] Otto Lilienthal, the first person to become highly successful with glider flights, was also the first to propose thin, curved airfoils that would produce high lift and low drag. Building on these developments as well as research carried out in their own wind tunnel, the Wright brothers flew the first powered airplane on December 17, 1903.

During the time of the first flights, Frederick W. Lanchester,[15] Martin Wilhelm Kutta, and Nikolai Zhukovsky independently created theories that connected circulation of a fluid flow to lift. Kutta and Zhukovsky went on to develop a two-dimensional wing theory. Expanding upon the work of Lanchester, Ludwig Prandtl is credited with developing the mathematics[16] behind thin-airfoil and lifting-line theories as well as work with boundary layers.

As aircraft speed increased, designers began to encounter challenges associated with air compressibility at speeds near or greater than the speed of sound. The differences in air flows under these conditions led to problems in aircraft control, increased drag due to shock waves, and structural dangers due to aeroelastic flutter. The ratio of the flow speed to the speed of sound was named the Mach number after Ernst Mach, who was one of the first to investigate the properties of supersonic flow. William John Macquorn Rankine and Pierre Henri Hugoniot independently developed the theory for flow properties before and after a shock wave, while Jakob Ackeret led the initial work on calculating the lift and drag of supersonic airfoils.[17] Theodore von Kármán and Hugh Latimer Dryden introduced the term transonic to describe flow speeds around Mach 1 where drag increases rapidly. This rapid increase in drag led aerodynamicists and aviators to disagree on whether supersonic flight was achievable until the sound barrier was broken for the first time in 1947 using the Bell X-1 aircraft.

By the time the sound barrier was broken, much of the subsonic and low supersonic aerodynamics knowledge had matured. The Cold War fueled an ever evolving line of high performance aircraft. Computational fluid dynamics began as an effort to solve for flow properties around complex objects and has rapidly grown to the point where entire aircraft can be designed using a computer, with wind-tunnel tests followed by flight tests to confirm the computer predictions. Knowledge of supersonic and hypersonic aerodynamics has also matured since the 1960s, and the goals of aerodynamicists have shifted from understanding the behavior of fluid flow to understanding how to engineer a vehicle to interact appropriately with the fluid flow. Designing aircraft for supersonic and hypersonic conditions, as well as the desire to improve the aerodynamic efficiency of current aircraft and propulsion systems, continues to fuel new research in aerodynamics, while work continues to be done on important problems in basic aerodynamic theory related to flow turbulence and the existence and uniqueness of analytical solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations.

Fundamental concepts

[edit | edit source]

Understanding the motion of air around an object (often called a flow field) enables the calculation of forces and moments acting on the object. In many aerodynamics problems, the forces of interest are the fundamental forces of flight: lift, drag, thrust, and weight. Of these, lift and drag are aerodynamic forces, i.e. forces due to air flow over a solid body. Calculation of these quantities is often founded upon the assumption that the flow field behaves as a continuum. Continuum flow fields are characterized by properties such as flow velocity, pressure, density and temperature, which may be functions of spatial position and time. These properties may be directly or indirectly measured in aerodynamics experiments, or calculated from equations for the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy in air flows. Density, flow velocity, and an additional property, viscosity, are used to classify flow fields.

Flow classification

[edit | edit source]Flow velocity is used to classify flows according to speed regime. Subsonic flows are flow fields in which air velocity throughout the entire flow is below the local speed of sound. Transonic flows include both regions of subsonic flow and regions in which the flow speed is greater than the speed of sound. Supersonic flows are defined to be flows in which the flow speed is greater than the speed of sound everywhere. A fourth classification, hypersonic flow, refers to flows where the flow speed is much greater than the speed of sound. Aerodynamicists disagree on the precise definition of hypersonic flow.

Compressibility refers to whether or not the flow in a problem can have a varying density. Subsonic flows are often assumed to be incompressible, i.e. the density is assumed to be constant. Transonic and supersonic flows are compressible, and neglecting to account for the changes in density in these flow fields when performing calculations will yield inaccurate results.

Viscosity is associated with the frictional forces in a flow. In some flow fields, viscous effects are very small, and solutions may neglect to account for viscous effects. These approximations are called inviscid flows. Flows for which viscosity is not neglected are called viscous flows. Finally, aerodynamic problems may also be classified by the flow environment. External aerodynamics is the study of flow around solid objects of various shapes (e.g. around an airplane wing), while internal aerodynamics is the study of flow through passages in solid objects (e.g. through a jet engine).

Continuum assumption

[edit | edit source]Unlike liquids and solids, gases are composed of discrete molecules which occupy only a small fraction of the volume filled by the gas. On a molecular level, flow fields are made up of many individual collisions between gas molecules and between gas molecules and solid surfaces. In most aerodynamics applications, however, this discrete molecular nature of gases is ignored, and the flow field is assumed to behave as a continuum. This assumption allows fluid properties such as density and flow velocity to be defined anywhere within the flow.

Validity of the continuum assumption is dependent on the density of the gas and the application in question. For the continuum assumption to be valid, the mean free path length must be much smaller than the length scale of the application in question. For example, many aerodynamics applications deal with aircraft flying in atmospheric conditions, where the mean free path length is on the order of micrometers. In these cases, the length scale of the aircraft ranges from a few meters to a few tens of meters, which is much larger than the mean free path length. For these applications, the continuum assumption holds. The continuum assumption is less valid for extremely low-density flows, such as those encountered by vehicles at very high altitudes (e.g. 300,000 ft/90 km)[4] or satellites in Low Earth orbit. In these cases, statistical mechanics is a more valid method of solving the problem than continuous aerodynamics. The Knudsen number can be used to guide the choice between statistical mechanics and the continuous formulation of aerodynamics.

Conservation laws

[edit | edit source]Aerodynamic problems are typically solved using fluid dynamics conservation laws as applied to a fluid continuum. Three conservation principles are used:

- Conservation of mass: In fluid dynamics, the mathematical formulation of this principle is known as the mass continuity equation, which requires that mass is neither created nor destroyed within a flow of interest.

- Conservation of momentum: In fluid dynamics, the mathematical formulation of this principle can be considered an application of Newton's Second Law. Momentum within a flow of interest is only created or destroyed due to the work of external forces, which may include both surface forces, such as viscous (frictional) forces, and body forces, such as weight. The momentum conservation principle may be expressed as either a single vector equation or a set of three scalar equations, derived from the components of the three-dimensional flow velocity vector. In its most complete form, the momentum conservation equations are known as the Navier-Stokes equations. The Navier-Stokes equations have no known analytical solution, and are solved in modern aerodynamics using computational techniques. Because of the computational cost of solving these complex equations, simplified expressions of momentum conservation may be appropriate to specific applications. The Euler equations are a set of momentum conservation equations which neglect viscous forces used widely by modern aerodynamicists in cases where the effect of viscous forces is expected to be small. Additionally, Bernoulli's equation is a solution to the momentum conservation equation of an inviscid flow, neglecting gravity.

- Conservation of energy: The energy conservation equation states that energy is neither created nor destroyed within a flow, and that any addition or subtraction of energy is due either to the fluid flow in and out of the region of interest, heat transfer, or work.

The ideal gas law or another equation of state is often used in conjunction with these equations to form a determined system to solve for the unknown variables.

Branches of aerodynamics

[edit | edit source]Aerodynamic problems are classified by the flow environment or properties of the flow, including flow speed, compressibility, and viscosity. External aerodynamics is the study of flow around solid objects of various shapes. Evaluating the lift and drag on an airplane or the shock waves that form in front of the nose of a rocket are examples of external aerodynamics. Internal aerodynamics is the study of flow through passages in solid objects. For instance, internal aerodynamics encompasses the study of the airflow through a jet engine or through an air conditioning pipe.

Aerodynamic problems can also be classified according to whether the flow speed is below, near or above the speed of sound. A problem is called subsonic if all the speeds in the problem are less than the speed of sound, transonic if speeds both below and above the speed of sound are present (normally when the characteristic speed is approximately the speed of sound), supersonic when the characteristic flow speed is greater than the speed of sound, and hypersonic when the flow speed is much greater than the speed of sound. Aerodynamicists disagree over the precise definition of hypersonic flow; a rough definition considers flows with Mach numbers above 5 to be hypersonic.[4]

The influence of viscosity in the flow dictates a third classification. Some problems may encounter only very small viscous effects on the solution, in which case viscosity can be considered to be negligible. The approximations to these problems are called inviscid flows. Flows for which viscosity cannot be neglected are called viscous flows.

Incompressible aerodynamics

[edit | edit source]An incompressible flow is a flow in which density is constant in both time and space. Although all real fluids are compressible, a flow problem is often considered incompressible if the effect of the density changes in the problem on the outputs of interest is small. This is more likely to be true when the flow speeds are significantly lower than the speed of sound. Effects of compressibility are more significant at speeds close to or above the speed of sound. The Mach number is used to evaluate whether the incompressibility can be assumed or the flow must be solved as compressible.

Subsonic flow

[edit | edit source]Subsonic (or low-speed) aerodynamics studies fluid motion in flows which are much lower than the speed of sound everywhere in the flow. There are several branches of subsonic flow but one special case arises when the flow is inviscid, incompressible and irrotational. This case is called potential flow and allows the differential equations used to be a simplified version of the governing equations of fluid dynamics, thus making available to the aerodynamicist a range of quick and easy solutions.[18]

In solving a subsonic problem, one decision to be made by the aerodynamicist is whether to incorporate the effects of compressibility. Compressibility is a description of the amount of change of density in the problem. When the effects of compressibility on the solution are small, the aerodynamicist may choose to assume that density is constant. The problem is then an incompressible low-speed aerodynamics problem. When the density is allowed to vary, the problem is called a compressible problem. In air, compressibility effects are usually ignored when the Mach number in the flow does not exceed 0.3 (about 335 feet (102 m) per second or 228 miles (366 km) per hour at 60 °F (16 °C)). Above 0.3, the problem should be solved by using compressible aerodynamics.

Compressible aerodynamics

[edit | edit source]According to the theory of aerodynamics, a flow is considered to be compressible if its change in density with respect to pressure is non-zero along a streamline. This means that - unlike incompressible flow - changes in density must be considered. In general, this is the case where the Mach number in part or all of the flow exceeds 0.3. The Mach .3 value is rather arbitrary, but it is used because gas flows with a Mach number below that value demonstrate changes in density with respect to the change in pressure of less than 5%. Furthermore, that maximum 5% density change occurs at the stagnation point of an object immersed in the gas flow and the density changes around the rest of the object will be significantly lower. Transonic, supersonic, and hypersonic flows are all compressible.

Transonic flow

[edit | edit source]The term Transonic refers to a range of flow velocities just below and above the local speed of sound (generally taken as Mach 0.8–1.2). It is defined as the range of speeds between the critical Mach number, when some parts of the airflow over an aircraft become supersonic, and a higher speed, typically near Mach 1.2, when all of the airflow is supersonic. Between these speeds, some of the airflow is supersonic, and some is not.

Supersonic flow

[edit | edit source]Supersonic aerodynamic problems are those involving flow speeds greater than the speed of sound. Calculating the lift on the Concorde during cruise can be an example of a supersonic aerodynamic problem.

Supersonic flow behaves very differently from subsonic flow. Fluids react to differences in pressure; pressure changes are how a fluid is "told" to respond to its environment. Therefore, since sound is in fact an infinitesimal pressure difference propagating through a fluid, the speed of sound in that fluid can be considered the fastest speed that "information" can travel in the flow. This difference most obviously manifests itself in the case of a fluid striking an object. In front of that object, the fluid builds up a stagnation pressure as impact with the object brings the moving fluid to rest. In fluid traveling at subsonic speed, this pressure disturbance can propagate upstream, changing the flow pattern ahead of the object and giving the impression that the fluid "knows" the object is there and is avoiding it. However, in a supersonic flow, the pressure disturbance cannot propagate upstream. Thus, when the fluid finally does strike the object, it is forced to change its properties -- temperature, density, pressure, and Mach number—in an extremely violent and irreversible fashion called a shock wave. The presence of shock waves, along with the compressibility effects of high-flow velocity (see Reynolds number) fluids, is the central difference between supersonic and subsonic aerodynamics problems.

Hypersonic flow

[edit | edit source]In aerodynamics, hypersonic speeds are speeds that are highly supersonic. In the 1970s, the term generally came to refer to speeds of Mach 5 (5 times the speed of sound) and above. The hypersonic regime is a subset of the supersonic regime. Hypersonic flow is characterized by high temperature flow behind a shock wave, viscous interaction, and chemical dissociation of gas.

Associated terminology

[edit | edit source]

The incompressible and compressible flow regimes produce many associated phenomena, such as boundary layers and turbulence.

Boundary layers

[edit | edit source]The concept of a boundary layer is important in many aerodynamic problems. The viscosity and fluid friction in the air is approximated as being significant only in this thin layer. This principle makes aerodynamics much more tractable mathematically.

Turbulence

[edit | edit source]In aerodynamics, turbulence is characterized by chaotic, stochastic property changes in the flow. This includes low momentum diffusion, high momentum convection, and rapid variation of pressure and flow velocity in space and time. Flow that is not turbulent is called laminar flow.

Aerodynamics in other fields

[edit | edit source]Aerodynamics is important in a number of applications other than aerospace engineering. It is a significant factor in any type of vehicle design, including automobiles. It is important in the prediction of forces and moments in sailing. It is used in the design of mechanical components such as hard drive heads. Structural engineers also use aerodynamics, and particularly aeroelasticity, to calculate wind loads in the design of large buildings and bridges. Urban aerodynamics seeks to help town planners and designers improve comfort in outdoor spaces, create urban microclimates and reduce the effects of urban pollution. The field of environmental aerodynamics studies the ways atmospheric circulation and flight mechanics affect ecosystems. The aerodynamics of internal passages is important in heating/ventilation, gas piping, and in automotive engines where detailed flow patterns strongly affect the performance of the engine. People who do wind turbine design use aerodynamics. A few aerodynamic equations are used as part of numerical weather prediction.

See also

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Wind Power's Beginnings (1000 B.C. - 1300 A.D.) Illustrated History of Wind Power Development". Telosnet.com.

- ↑ Berliner, Don (1997). Aviation: Reaching for the Sky. The Oliver Press, Inc.. p. 128. ISBN 1-881508-33-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=Efr2Ll1OdqMC&pg=PA128&dq&hl=en#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Ovid; Gregory, H. (2001). The Metamorphoses. Signet Classics. ISBN 0-451-52793-3. OCLC 45393471.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Anderson, John David (1997). A History of Aerodynamics and its Impact on Flying Machines. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45435-2. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "andersonhist" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Newton, I. (1726). Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Book II.

- ↑ "Hydrodynamica". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ↑ Navier, C. L. M. H. (1827). Memoire sur les lois du mouvement des fluides. Memoires de l'Academie des Sciences (6), 389-440.

- ↑ Stokes, G. (1845). On the Theories of the Internal Friction of Fluids in Motion. Transaction of the Cambridge Philosophical Society (8), 287-305.

- ↑ "U.S Centennial of Flight Commission - Sir George Cayley". Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

Sir George Cayley, born in 1773, is sometimes called the Father of Aviation. A pioneer in his field, he was the first to identify the four aerodynamic forces of flight - weight, lift, drag, and thrust and their relationship. He was also the first to build a successful human-carrying glider. Cayley described many of the concepts and elements of the modern airplane and was the first to understand and explain in engineering terms the concepts of lift and thrust.

- ↑ d'Alembert, J. (1752). Essai d'une nouvelle theorie de la resistance des fluides.

- ↑ Kirchhoff, G. (1869). Zur Theorie freier Flussigkeitsstrahlen. Journal fur die reine und angewandte Mathematik (70), 289-298.

- ↑ Rayleigh, Lord (1876). On the Resistance of Fluids. Philosophical Magazine (5)2, 430-441.

- ↑ Renard, C. (1889). Nouvelles experiences sur la resistance de l'air. L'Aeronaute (22) 73-81.

- ↑ Lanchester, F. W. (1907). Aerodynamics.

- ↑ Prandtl, L. (1919). Tragflügeltheorie. Göttinger Nachrichten, mathematischphysikalische Klasse, 451-477.

- ↑ Ackeret, J. (1925). Luftkrafte auf Flugel, die mit der grosserer als Schallgeschwindigkeit bewegt werden. Zeitschrift fur Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt (16), 72-74.

- ↑ Katz, Joseph (1991). Low-speed aerodynamics: From wing theory to panel methods. McGraw-Hill series in aeronautical and aerospace engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-050446-6. OCLC 21593499.

Further reading

[edit | edit source]General aerodynamics

- Anderson, John D. (2007). Fundamentals of Aerodynamics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-125408-0. OCLC 60589123.

- Bertin, J. J.; Smith, M. L. (2001). Aerodynamics for Engineers (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-064633-4. OCLC 47297603.

- Smith, Hubert C. (1991). Illustrated Guide to Aerodynamics (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-8306-3901-2. OCLC 24319048.

- Craig, Gale (2003). Introduction to Aerodynamics. Regenerative Press. ISBN 0-9646806-3-7. OCLC 53083897.

Subsonic aerodynamics

- Katz, Joseph; Plotkin, Allen (2001). Low-Speed Aerodynamics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66552-3. OCLC 43970751.

Transonic aerodynamics

- Moulden, Trevor H. (1990). Fundamentals of Transonic Flow. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89464-441-6. OCLC 20594163.

- Cole, Julian D; Cook, L. Pamela (1986). Transonic Aerodynamics. North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-87958-7. OCLC 13094084.

Supersonic aerodynamics

- Ferri, Antonio (2005). Elements of Aerodynamics of Supersonic Flows (Phoenix ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-44280-2. OCLC 58043501.

- Shapiro, Ascher H. (1953). The Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Compressible Fluid Flow, Volume 1. Ronald Press. ISBN 978-0-471-06691-0. OCLC 11404735.

- Anderson, John D. (2004). Modern Compressible Flow. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-124136-1. OCLC 71626491.

- Liepmann, H. W.; Roshko, A. (2002). Elements of Gasdynamics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41963-0. OCLC 47838319.

- von Mises, Richard (2004). Mathematical Theory of Compressible Fluid Flow. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43941-0. OCLC 56033096.

- Hodge, B. K.; Koenig K. (1995). Compressible Fluid Dynamics with Personal Computer Applications. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-308552-X. OCLC 31662199.

Hypersonic aerodynamics

- Anderson, John D. (2006). Hypersonic and High Temperature Gas Dynamics (2nd ed.). AIAA. ISBN 1-56347-780-7. OCLC 68262944.

- Hayes, Wallace D.; Probstein, Ronald F. (2004). Hypersonic Inviscid Flow. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43281-5. OCLC 53021584.

History of aerodynamics

- Chanute, Octave (1997). Progress in Flying Machines. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29981-3. OCLC 37782926.

- von Karman, Theodore (2004). Aerodynamics: Selected Topics in the Light of Their Historical Development. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43485-0. OCLC 53900531.

- Anderson, John D. (1997). A History of Aerodynamics: And Its Impact on Flying Machines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45435-2. OCLC 228667184.

Aerodynamics related to engineering

Ground vehicles

- Katz, Joseph (1995). Race Car Aerodynamics: Designing for Speed. Bentley Publishers. ISBN 0-8376-0142-8. OCLC 181644146.

- Barnard, R. H. (2001). Road Vehicle Aerodynamic Design (2nd ed.). Mechaero Publishing. ISBN 0-9540734-0-1. OCLC 47868546.

Fixed-wing aircraft

- Ashley, Holt; Landahl, Marten (1985). Aerodynamics of Wings and Bodies (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-64899-0. OCLC 12021729.

- Abbott, Ira H.; von Doenhoff, A. E. (1959). Theory of Wing Sections: Including a Summary of Airfoil Data. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-60586-8. OCLC 171142119.

- Clancy, L.J. (1975). Aerodynamics. Pitman Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-273-01120-0. OCLC 16420565.

Helicopters

- Leishman, J. Gordon (2006). Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85860-7. OCLC 224565656.

- Prouty, Raymond W. (2001). Helicopter Performance, Stability, and Control. Krieger Publishing Company Press. ISBN 1-57524-209-5. OCLC 212379050.

- Seddon, J.; Newman, Simon (2001). Basic Helicopter Aerodynamics: An Account of First Principles in the Fluid Mechanics and Flight Dynamics of the Single Rotor Helicopter. AIAA. ISBN 1-56347-510-3. OCLC 47623950.

Missiles

- Nielson, Jack N. (1988). Missile Aerodynamics. AIAA. ISBN 0-9620629-0-1. OCLC 17981448.

Model aircraft

- Simons, Martin (1999). Model Aircraft Aerodynamics (4th ed.). Trans-Atlantic Publications, Inc.. ISBN 1-85486-190-5. OCLC 43634314.

Related branches of aerodynamics

Aerothermodynamics

- Hirschel, Ernst H. (2004). Basics of Aerothermodynamics. Springer. ISBN 3-540-22132-8. OCLC 228383296.

- Bertin, John J. (1993). Hypersonic Aerothermodynamics. AIAA. ISBN 1-56347-036-5. OCLC 28422796.

Aeroelasticity

- Bisplinghoff, Raymond L.; Ashley, Holt; Halfman, Robert L. (1996). Aeroelasticity. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-69189-6. OCLC 34284560.

- Fung, Y. C. (2002). An Introduction to the Theory of Aeroelasticity (Phoenix ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-49505-1. OCLC 55087733.

Boundary layers

- Young, A. D. (1989). Boundary Layers. AIAA. ISBN 0-930403-57-6. OCLC 19981526.

- Rosenhead, L. (1988). Laminar Boundary Layers. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65646-2. OCLC 17619090.

Turbulence

- Tennekes, H.; Lumley, J. L. (1972). A First Course in Turbulence. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-20019-8. OCLC 281992.

- Pope, Stephen B. (2000). Turbulent Flows. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59886-9. OCLC 174790280.

External links

[edit | edit source]- NASA Beginner's Guide to Aerodynamics

- Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's How Things Fly website

- Aerodynamics for Students

- Aerodynamics for Pilots

- Aerodynamics and Race Car Tuning

- Aerodynamic Related Projects

- eFluids Bicycle Aerodynamics

- Application of Aerodynamics in Formula One (F1)

- Aerodynamics in Car Racing

- Aerodynamics of Birds

- Aerodynamics and dragonfly wings

{{w:Authority control}} w:Category:Aerospace engineering