Thinking Tools

—Boosting Imagination

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Imagine what we could accomplish if we could improve our ability to imagine new solutions and discover more important problems to solve. Fortunately, a variety of thinking tools exist that can help us do exactly that.

This course presents a collection of tools that are useful in creative problem solving which generally follows the steps[1] of clarify, ideate, develop, and implement. Throughout the process it is important to navigate, integrate and prioritize.

Throughout creative problem solving it is important to determine if divergent thinking is needed to create new alternatives, or if convergent thinking is needed to choose the best option from among existing alternatives. The process alternates between divergent and convergent thinking often as each new phase is entered.

Use the thinking tools presented in this course when you need a better idea.

Objectives

[edit | edit source]| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

| Attribution: User lbeaumont created this resource and is actively using it. Please coordinate future development with this user if possible. |

The objectives of this course are to:

- help students boost their creativity;

- introduce students to a variety of thinking tools;

- improve problem solving abilities; and

- assist in transforming good ideas into better ideas.

This course introduces many useful thinking tools, and many others exist. Please browse this inventory of additional thinking tools to continue to improve your ability to solve problems and think creatively.

This is a course in the possibilities curriculum, currently being developed as part of the Applied Wisdom Curriculum.

The course contains many hyperlinks to further information. Use your judgment and these link following guidelines to decide when to follow a link, and when to skip over it.

If you wish to contact the instructor, please click here to send me an email or leave a comment or question on the discussion page.

This Quick Reference on thinking tools may provide a helpful summary and reference.

Clarify—Strategic Thinking

[edit | edit source]The first phase in solving problems is to clearly identify the problem to be solved. The companion course on Problem Finding addresses this topic in depth. A brief introduction to identifying problems is provided here.

A problem is a gap between a perceived state and a desired state. What may at first appear as a problem may be recognized as an opportunity—a chance for substantial gain. It is important to recognized that any proposed solution is not a problem statement.

The companion course on Reframing the Problem[2] addresses opportunities to attain more important goals by “telling a different story”.

During the clarify phase some vague notion of a problem, opportunity, or call to action will be transformed into a precise problem statement.

The essential task in the clarify phase is to ask, “What is the problem?” and continue to refine answers until a complete and precise problem statement is formed.

Early in the clarify phase we will work with challenge statements, which are general statements of some problem to be solved.

To form challenge statements:[3]

- Begin with an open question starter: (“How might …, What might, … )

- Identify an owner (I, you, we, our department, the team, …)

- Include a verb to identify an action, (create, improve, increase, reduce, expand, …)

- Identify the object

For example: “How might I create a course on creative thinking tools?”

Throughout the clarify phase, the team will define goals, gather data, and formulate refined challenge statements.

The clarify phase is complete when a more complete problem statement is formed and adopted by the team.

Begin the clarify phase by asking:

- What do you want to have happen?

- What are the opportunities?

And continue by asking:

- What are the obstacles?

- Are the identified obstacles real?

- What obstacles are we overlooking?

Here are some tools that can help.

The Five Ws

[edit | edit source]A tool that is useful at this stage, and at many other stages, is asking Who, what, where, when, why, and how? to get a clearer and deeper understanding of the problem.

Begin with the end in mind.[4] Describe how it will look, or how it will be, when this problem is solved. If the problem is “I am overweight” then a possible outcome is “Now I can wear the clothes I wore in High School.” If the problem is “I am often late to work” then a possible outcome is “I arrive at work on time every day next month.” If the problem is “global conflict”, then a possible outcome is “Peace on earth, good will toward all.”

The Phoenix Checklist

[edit | edit source]Using the Phoenix Checklist can help to clarify a problem statement. The list is designed to help explore challenges from many different viewpoints.

SMART Goals

[edit | edit source]Goals statements are most clear, realistic, actionable, and specific when they are stated as SMART goals.

SMART Goals are:

- Specific – they target a specific area for improvement.

- Measurable – they quantify or at least suggest an indicator of progress.

- Assignable – it is clear who is responsible for achieving the outcome.

- Realistic – state what results can realistically be achieved, given available resources.

- Time-related – specify when the result(s) will be achieved.

The challenge now becomes “How can we attain this SMART Goal?”

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Scan this list of example problem topics.

- Choose one of the topics listed, or choose some other problem you are interested in.

- Answer who, what, where, when, why, and how this problem will be addressed.

- Address the Phoenix Checklist questions to further clarify the problem.

- Identify the end state that best represents how it will be when this problem is solved.

- Revise and write down that end state as a SMART goal.

- Ensure the written goal statement is specific, measurable, assigned, realistic, and time-related.

Webbing Tool

[edit | edit source]Often the problem as it is initially presented is not the real problem that needs to be solved. The Webbing tool[5] can help you perform divergent thinking, better understand the problem, describe why it is important, explore related and perhaps more relevant problems, and identify the obstacles to achieving your goal. The webbing tool can help move from the problem as initially presented, to the problem as it is better understood.

Refer to the example diagram on the right. Begin by writing the challenge statement in the middle of the page. In this example “Lose Weight” is the challenge statement. Ask “Why is this important?” and record each reason in an ellipse, connected to the goal by an arrow. Keep asking “Why?” (to move deeper) and “Why else?” (to move laterally) to record all the reasons the goal is important. These are shown in the green ellipses in the figure. Now ask “What is stopping you from achieving the goal?” and “What else?” and record each reason in an ellipse. These are shown in red. Repeatedly asking, “what is stopping you?” can often create a path from an abstract problem to a more concrete action that can be taken. This can provide new insights into the problem. For example, it may be helpful to decide to stop buying snacks, or drink something with less sugar than soda as an intermediate goal toward losing weight.

Add detail to the web as each “why?” question is asked, considered, and answered. The 5 Whys technique can be helpful in exploring the cause-and-effect relationships unfolding in the web.

Mind mapping tools may be useful in constructing, improving, and sharing your web.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose a problem to work on for this assignment. You may choose a problem from this list of example problem topics or choose some other problem you want to work on.

- Begin using the webbing tool as described above using the chosen challenge statement as the focus.

- Ask “Why is this important?” and record each reason in an ellipse. Ask “Why else?” and record more reasons.

- Ask “What is stopping you from achieving the goal?” and “What else?” and record each reason in an ellipse.

- Continue to add detail to the webbing tool diagram.

- Examine the emerging web (network diagram) to identify more suitable problem statements (suggested by the green ellipses) and to identify actions that can help to achieve the goal (suggested by the red ellipses).

Storyboarding

[edit | edit source]We use storyboarding to illustrate the steps from the current reality to the desired future state. Because it is a visual tool, it can have a motivational impact as it clarifies what needs to be done, how each step along the way can be completed, and what getting it done can look like.

These are the steps to create a storyboard:

- Sketch at least six blank panels.

- Illustrate the current reality in the first panel

- Illustrate the desired future state in the last panel

- In each intermediate panel, illustrate some step along the way, or achievement of some milestone along the path toward the desired future state.

- Add additional intermediate panels as needed.

The resulting weight loss storyboard is shown in this example illustration.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose a problem to work on for this assignment. You may choose this from the list of example problem topics or choose some other problem you want to work on.

- Follow the steps described above to create a storyboard illustrating the steps you plan to take to proceed from the present state to the desired future state.

Stating a Problem

[edit | edit source]The outcome of the clarify stage is a well-chosen and well-written problem statement.

Philosopher John Dewey noted “It is a familiar and significant saying that a problem well put is half-solved”.[6] Albert Einstein noted "the formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution".[7] Research has shown that problem identification is the strongest predictor of program effectiveness.

Problem statements can begin with the vague notion that “we ought to do something” and evolve from a challenge statement to a Hoshin planning statement in the form of “objective by means” to a fully-formed problem statement.

Recall that a challenge statement

- Begins with an open question starter: (“How might …, What might, … )

- Identifies an owner (I, you, we, our department, the team, …)

- Includes a verb to identify an action, (create, improve, increase, reduce, expand, …)

- And identifies the object.

For example: “How can I lose weight?”

A Hoshin planning objective statement includes:[8]

- An objective describing the end state

- “by” to indicate the means that will be the tactic used to achieve the objective,

- A statement of means, identifying how the end state will be accomplished.

For example: “Lose weight by exercising more”

A fully formed problem statement includes:[9]

- The ideal outcome, end state, vision, or objective,

- The current reality, a description of the current state

- The consequences, benefits, or reasons to undertake this change, and

- A proposal for how the change can be accomplished.

For example: (Ideal) I will lose 30 pounds of weight in the next 6 months and be able to fit comfortably into the suit I wore at our wedding.

(Reality) I currently weigh 215 pounds and have been gaining weight at more than 5 pounds per year for the past 8 years. I get very little exercise, I don’t enjoy exercising, I snack often, eat out often, and I eat unhealthy, high calorie, low nutrition foods.

(Consequences) This weight loss will improve my appearance and make me healthier. I will feel better and I am likely to live longer. Continuing to gain weight is unhealthy and will soon become dangerous.

(Proposal) I will achieve this weight loss by eliminating soda from my diet, reducing sugar in my diet, eating healthier foods, learning to cook at home, eating out less often, walking outdoors often, finding a physical activity I enjoy doing, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, and walking instead of driving as often as practical.

This problem statement is readily constructed from the materials developed in the webbing tool and storyboard examples.

Assignment:

[edit | edit source]- Choose a problem to work on for this assignment. You may choose from the list of example problem topics or choose some other problem you want to work on.

- Write the problem statement in the form of a challenge statement.

- Write the problem statement as a Hoshin planning objective statement in the form of “objective by means”.

- Follow the example above and write a fully formed problem statement including the ideal, the reality, the consequences, and the proposal.

Ideate—Blue Sky Thinking, Nonjudgmental

[edit | edit source]Ideation is the creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas. The goal of ideation is to create many ideas that might help us better understand the problem or lead to some solutions. The outcome is a tentative solution, solution concept, or solution approach.

The ideation phase emphasizes divergent thinking Elements of divergent thinking[10] include:

- Fluency—Quickly producing many ideas in response to an open-ended prompt, challenge, or unstructured problem or opportunity.

- Flexibility—Taking a variety of approaches. Thinking different. Drawing on backgrounds and experiences from a variety of disciplines, cultures, or professions.

- Originality—Unique, unexpected, unusual, and outside typical expectations.

- Elaboration—Adding detail to an idea, in-depth understanding, embellishment, richness and complexity.

- Visualization—The ability to fantasize, imagine, or see people, places, things, actions, or events in your mind’s eye or as expressive illustrations. The ability to create and manipulate mental images.

- Imagination—The ability to produce and explore ideas, concepts, environments, or events that do not originate though sensory perception.

- Intuition—The ability to acquire knowledge without proof, evidence, or conscious reasoning, or without understanding how the knowledge was acquired. The ability to make connections and see relationships that are not explicit, clear, or apparent. The ability to make mental leaps and close gaps in the available information.

- Extending Boundaries—The ability to go beyond what is presented, apparent, or typical. The ability to consider events in a new or different context.

- Transformation—The ability to see new meanings, applications, uses, forms of some ideal, object, or concept.

- Alternative Perspectives—The ability to adopt a variety of viewpoints when examining, understanding, evaluating, extending, or presenting an idea, concept, event, or object.

Many tools can help us ideate. Several are described in the following sections.

Secondary Research

[edit | edit source]Secondary research can help answer the question “What is already known about this problem?” This is often the first place to start understanding the problem better.

Because so much information is readily available these days it makes sense to begin solving problems by searching available information. Useful information sources include: general web searches such as Google Search, specialized web searches such as Google Scholar, on-line encyclopedias such as Wikipedia and Scholarpedia; libraries, books, periodicals, Academic journals, News media, archives, standards, written law, bibliographic databases, and others.

Depending on the topic being researched, you may be flooded with information, or you may find it difficult to find anything at all. For example, a web search on the term “losing weight” returns more than one billion results. With so many responses it becomes important to be selective even in the early stages of research. Consider the reliability of the source and the relevance of the information. The Wikipedia tutorial “Search Engine Test” provides useful guidance for interpreting search engine results. The Wikipedia policy on Reliable Sources provides useful guidance in assessing the reliability of various information sources. Include a variety of intellectually honest viewpoints when selecting information sources. Dismiss intellectually dishonest sources.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose some topic or problem to research.

- Use any of the information sources listed above to learn more about your topic.

- Identify at least three sources you have determined to be reliable. How do you know?

- Identify any sources that are likely to be unreliable. How do you know?

Benchmarking

[edit | edit source]Benchmarking can help us answer the question “How do they do that?

The simplest approach to benchmarking is to identify some existing solution to your problem, or some related problem, and learn all you can from that solution. We benchmark every day when we ask friends to name their favorite restaurants, smartphone applications, books to read, or college to attend. More formal benchmarking efforts may follow a comprehensive procedure.

Creative people claim, “Good artists copy; great artists steal.”[11] We certainly don’t advocate theft, plagiarism, or isolation. We also don’t advocate reinventing the wheel, or ignorance. Begin with the best practice in mind.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose some topic or problem to research.

- Identify at least three successful solutions to that problem or a related problem.

- What can you learn by studying those existing solutions?

- What did you learn? How have you made use of what was learned?

Appreciative Inquiry

[edit | edit source]Appreciative inquiry uses ways of asking questions and envisioning the future to foster positive relationships and build on the present potential of a given person, organization or situation. The most common model utilizes a cycle of four processes, which focus on what it calls:

- DISCOVER: The identification of organizational processes that work well.

- DREAM: The envisioning of processes that would work well in the future.

- DESIGN: Planning and prioritizing processes that would work well.

- DESTINY (or DEPLOY): The implementation (execution) of the proposed design.[15]

The aim is to build – or rebuild – organizations around what works, rather than trying to fix what doesn't. Appreciative Inquiry practitioners describe this approach as a complement to problem solving.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose some topic, problem, or success to research.

- Dialogue with the participants.

- Identify what is working well now.

- Identify the personal, organizational, procedural, technical, informational, and cultural elements that contribute to this success.

- How can that success be sustained and expanded?

- Sustain and expand the existing successes.

Thinking outside the box

[edit | edit source]

An early step in ideation is to think outside the box which means to think differently, unconventionally, or from a new perspective. This phrase often refers to novel or creative thinking. The goal of thinking outside the box is to go beyond the unspecified but imagined barriers people typically perceive that unhelpfully limits their thinking.

For many years people struggled to get ketchup to flow from its traditional bottle. Shaking, hitting, scooping, waiting, yelling, and shaking again eventually resulted in too much or too little ketchup often landing in the wrong place. Eventually someone thought outside the bottle, turned it upside down, and invented the convenient “upside down” ketchup bottle.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]The “nine dots” problem illustrates obstacles we often face when challenged to think outside the box.

- Look at this image of nine dots.

- Link all 9 dots using four straight lines or fewer, without lifting the pen and without tracing the same line more than once. Be assured that one straightforward solution exists, and several more-creative solutions also exist.

- After you have succeeded, or after you have worked at this problem for some time and choose to give up, look at the solution provided here.

- What insight was key to finding a solution?

- What unspecified boundaries prevent you from imagining solutions to some real-world problem you are facing?

- How can the solution to the nine dots problem serve as a useful metaphor or inspiration in exploring problems and solutions?

Metaphor—What is this problem like?

[edit | edit source]A metaphor is a figure of speech that directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide clarity or identify hidden similarities between two ideas. One of the most commonly cited examples of a metaphor in English literature is the "All the world's a stage" monologue from As You Like It.

More than a rhetorical tool, a conceptual metaphor is a fundamental mechanism of the mind that allows us to use what we know about our physical and social experience to provide understanding of countless other subjects.[12]

If we can find a good metaphor for the problem we are facing that metaphor can help us solve problems by creating analogies between the unsolved problem and something similar we are already familiar with. Some metaphors may be useful, and others may be limiting.

The phrase “war on drugs” is a metaphor that frames efforts to reduce illicit drug usage as a battle to be won, with drugs themselves identified as the enemy. This may be helpful in finding various military-based solutions to the problem. However, it may also limit thinking to approaches based on military conflicts. The phrase “war on drugs” is a solution statement, not a problem statement as discussed in the sections above. Problem statements such as “reduce illicit drug usage” or “reduce the damage caused by drug usage”, or “reduce demand for drugs” allow thinking to extend beyond a military mindset, and avoid prematurely identifying a single cause of the problem. Alternative metaphors such as “Drugs are deadly candy”, or “Drug users are patients needing treatment”, or “Drugs are irresistible temptations” can focus thinking toward preventing or treating addiction.

Consider these common metaphors:

- Time is money

- Love is a journey

- Love is war

- Love is a rose

- I am a couch potato

- Life is a box of chocolates

A metaphor often has the form X is Y.

Here are some metaphors related to weight loss:

- Losing weight is a war on calories.

- Losing weight is a marathon.

- Exercise is hell.

- Obesity is an anchor.

- Losing weight is a walk in the park.

- Losing weight is exuberance in action.

- Lost weight is liberty.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Consider each of the “losing weight” metaphors above. What solutions does each metaphor suggest? What solutions does each metaphor distract us from?

- Choose a problem from this list of example problem topics.

- Recast that problem as at least three distinct metaphors.

- What solutions does each metaphor suggest? What solutions does each metaphor distract us from?

- Repeat steps 3-5 for some real problem you are facing.

Brainstorming

[edit | edit source]Brainstorming is collection of methods that helps people generate new ideas and solutions on some topic. Brainstorming is often used to identify many ideas that may help solve an identified problem.

Although brainstorming is the best-known technique for ideation, it is only one of many useful tools.

The key principles used in brainstorming are:

- Defer Judgement, and

- Reach for quantity.

This requires the group to reduce social inhibitions among group members, stimulate idea generation, and increase overall creativity of the group. Participants withhold criticism, welcome wild ideas, and combine and improve ideas throughout brainstorming sessions.

Following these steps can help a group hold a successful brainstorming session:

- Identify the topic of the brainstorming session. The problem must require generating ideas, such as generating many possible product names, rather than a judgment or decision.

- Gather a group of participants. Any group can be successful, however a group of about 12 participants including both novices and experts is ideal.

- Ask participants to contribute their ideas. Simply calling out short statements like “call it ‘New Coke!’” or “How about Elephants?” as participants get ideas is often the most effective approach.

- Encourage participants to contribute any idea that comes to mind. Wild and unexpected answers are particularly valuable because they increase the scope of the participants’ imagination.

- A moderator writes the ideas down immediately on an easel, marker board, chalk board or display screen that is clearly visible to all participants.

- Ensure participants suspend judgement throughout the session. If anyone criticizes, analyzes, discusses, or disparages any of the suggestions made, pause and gently remind the group to defer judgments and reach for quantity.

- It is helpful for the moderator to notice any participants who are silent or seem to be overwhelmed by the pace of the group. Pause the group and kindly ask each such reticent participant for any ideas they have. Allow adequate time for them to respond.

- The group is likely to pause as if they are stuck or temporarily out of ideas. Wait patiently for this interval to pass because it is likely the best ideas are yet to come. Remain ready to resume creating and recording ideas.

- When the session finally does end, ensure each of the participants gets a copy of the ideas recorded.

- At some later date hold an evaluation session to choose the ideas that are directly useful, and extract from impractical or bizarre ideas the functional kernel of an idea that can be generalized in some useful way.

Edward de Bono argues that the value of a brainstorming session lies in the formality of the setting. He describes brainstorming as a formal setting for the use of lateral thinking.[13]

Several variations on this basic brainstorming method can also be productive.

In nominal group technique, participants are asked to write their ideas anonymously. Then the facilitator collects the ideas and the group votes on each idea. The vote can be as simple as a show of hands in favor of a given idea. This process is called distillation.

Brainwriting includes both individual and group approaches. In brainwriting members write their ideas on a piece of paper and then pass it along to others who add their own ideas.

In reverse brainstorming, the challenge statement is reversed, for example the group may consider how to decrease sales. This can highlight obstacles to increasing sales and encourage other points of view.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Follow the brainstorming steps described above to generate ideas related to some problem you wish to solve.

Forced Relationships

[edit | edit source]Forced relationships can stimulate associative thoughts and expand group members’ thinking. Asking “How can an elephant help us solve our problem?” is an example of a forced relationship. Introducing the idea of an elephant is likely to be so different from how the group was thinking it often stimulates a series of very new ideas.

Force new relationships by asking the group to connect ideas to some word chosen at random. Several random word generators are available to help with this. It is important to insist the group consider the first random word presented. Waiting for “the word you were looking for” only perpetuates stale thinking.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose a problem to work on.

- Informally brainstorm a few solution ideas.

- Choose a random word generator to use for this exercise. This might be:

- The wordcounter random word generator, or

- The Desiquintans Random Noun Generator, or

- Some other random word generator.

- Use your chosen random word generator to choose some word at random. Stay with the first word chosen regardless of how unsuitable it may seem.

- Generate ideas inspired by that random word that could help solve the problem.

- After several new ideas are stimulated, choose another random word and continue the process.

Hieroglyphic Hints

[edit | edit source]Hieroglyphic hints provide an alternative approach to stimulating associative thoughts and expanding group members’ thinking. The hieroglyphic hints page displays several hieroglyphic symbols chosen at random. These can invite your imagination to free-associate ideas, stimulate and expand your imagination and discover a new approach to solving problems.[14]

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose a problem to work on for this assignment. Write it down.

- Select a row of hieroglyphic symbols at random from the hieroglyphic hints page.

- As you study each symbol, allow yourself to free associate from it. Wonder as you ask: What is it? Why was this symbol chosen? What might this mean? What does this make me think of? How can this symbol help solve my problem?

- Write down your various interpretations of the symbol.

- Draw some connection from the problem you are working on to your interpretation of each symbol.

- Seek a clue, insight, idea, or connection to some new approach to solving your problem.

Lateral Thinking

[edit | edit source]Over the past few decades Edward de Bono has developed several problem solving concepts, tools, and techniques he calls Lateral Thinking. He contrasts lateral thinking with the typical approaches he calls vertical thinking. Where vertical thinking digs deeper, lateral thinking digs in a new place.

The following table contrasts traditional vertical thinking with salient features of lateral thinking.

| Vertical Thinking | Lateral Thinking |

|---|---|

| Historical continuity | Generating new alternatives |

| Building upon accepted assumptions | Challenging assumptions |

| Leveraging and extending existing patterns | Restructuring familiar patterns |

| Sequential Steps | Escape to new patterns, reversal |

| Analytical | Generative, Provocative, disruptive |

| Construction | Creative destruction |

| Correctness | Novelty, random stimulation, different |

| Serious, stern, grave, responsible, deep, intense | Playful |

| Dig the same hole deeper | Dig a hole in a new place |

Some of the tools and techniques developed from lateral thinking are described in this course, including PO, forced relationships using random words, and the six thinking hats. However, there are too many tools and techniques to cover adequately here. I encourage interested students to read and study more about lateral thinking, beginning with the book Lateral Thinking: Creativity Step by Step[15], and many others by Edward de Bono.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Part 1:

- Think of as many uses as you can for a paperclip.

- Write these as a list. List as many uses as you can.

- Keep going, find more uses.

- Compare your list to this list of 100 uses of a paperclip.

Part 2:

- Choose several puzzles from these sources:

- See, for example http://lateralpuzzles.com/puzzles/index.php

- Classic Lateral Thinking Exercises See: https://leoniehallatinnovationiq.wordpress.com/2010/08/24/lateral-thinking-brain-teasers/

- and the book Hall of Fame Lateral thinking puzzles, Paul Sloane & Des MacHale[16]

- Solve the puzzles you have chosen

PO – Provocative Operation

[edit | edit source]Edward de Bono created the term “Po” as part of a lateral thinking technique to indicate movement—a shift, backing off judgment, and invite movement forward in a new direction. Po is as provocative operation used to signal a deliberate intent to move thinking forward to a new place where new ideas or solutions may be found. Po can be used as an interjection — as a creative alternative to “yes” or “no” — indicating that you reject the false dichotomy, or that you need to know more before responding to an idea or thought. Imagine it as a word that means: "I think I know what you mean, but can you say it in another way so I may more fully understand you". Its use indicates respect for the other. It is considered a language lubricant — to encourage more conversation, exploration, and explanation. It may mean “supPOse things were different” or simply “let’s pause here and consider other ways to proceed.”

As an example, when you are in a business meeting where a co-worker states "Sales are dropping off because our product is perceived as old fashioned" you, or others at the meeting can respond with:

- po: Change the color of the packaging

- po: Flood the market with even older-looking products to make it seem more appealing

- po: Call it retro

- po: Sell it to old people

- po: Sell it to young people as a gift for old people

- po: Open a museum dedicated to it

- po: Market it as a new product

Some of the above ideas may be impractical, not sensible, not business-minded, not politically correct, or just plain daft. The value of these ideas is that they move thinking from a place where it is entrenched to a place where it can move. The above ideas might develop into more practical ideas such as:

po: Change the color of the packaging → update the product casing to bring it up to date as is often done with electronic goods.

po: Call it retro → instead of retro say "tried and tested" or "industry standard"

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Introduce use of “Po” to your working group or close associates.

- Practice using “Po” in a private setting, perhaps with family or close friends to gain experience and become comfortable with it.

- Describe its benefits and use to a group of coworkers. Invite them to discuss using the technique and to share their concerns.

- Ask them if they are willing to try “Po” when the group works together. Consider “Po – we are using Po effectively to move the team forward” and allow the discussion to unfold.

- Use Po effectively and routinely when this group meets to solve problems.

- Extend your use of Po to other working groups.

Developing Ideas

[edit | edit source]The tools described so far emphasized fluency rather than elaboration. The following tools help consider ideas further, develop ideas to better understand them, imagine their usefulness, capture the most benefit from a nascent idea and often use one idea as a springboard to generate additional ideas.

Idea Notebooks

[edit | edit source]Keep a journal, diary, or other notebook where you record new ideas and revisit and develop ideas previously recorded. Keep this with you. Write in it often, study it often.

Synetics

[edit | edit source]Syntectics is a collection of problem-solving tools, collaboration methods, and techniques originated by George M. Prince and William J.J. Gordon originating in the 1950’s.

They studied recordings of thousands of business meetings to understand what happens. They were particularly interested to learn what behaviors inhibit the discussion, preempt creative thinking, and shut down exploration of new ideas. They then worked to test a variety of approaches that encourage creative thinking and helpful consideration of creative ideas.

Based on their extensive analysis of how meetings unfold, they pioneered concepts of client ownership of idea selection, metaphor, open minded communications, suspending judgement, idea development, climate factors that encourage or discourage ideation, and the prevalence and importance of avoiding the discount and revenge cycle.[17]

Their approach to idea development is presented here, and other Synetics contributions appear in various sections of this course as relevant topics are addressed.

Synetics Idea Development

[edit | edit source]The Synetics founders observed that many ideas created in brainstorming sessions or that arose in ideation meetings were lost because they were never understood, or never developed. They introduced the following approach to getting more out of the generated ideas:

- Insist the client own idea selection during brainstorming sessions or other idea generating activities. This overcomes the “not invented here” problem that often inhibits many good ideas from being embraced by people or organizations who could benefit from them. The team recognizes that opinions are not relevant unless they are requested by the client.

- The problem owner, typically the client, is expected to check his or her understanding of the idea by discussing it with the idea originator before evaluating the idea.

- The idea must be well understood before identifying important shortcomings.

- Ideas are evaluated in stages:

- Select ideas for newness and appeal

- Build on the nascent idea to create a more fully formed idea. (Fully bake appealing half-baked ideas.)

- Evaluate the idea with an open mind, first emphasizing the benefits and potential before identifying important shortcomings. (as is done when using POINT)

- Modify the idea to overcome shortcomings and create more opportunities and greater benefits.

- Use the idea to support some new course of action.

Varying Attributes

[edit | edit source]New products, concepts, or solutions can often be inspired by varying the attributes of some existing product. Consider chairs for example. A typical chair has four legs, a squarish seat, and a back. Removing the back produces a stool. Using three legs provides a three-legged stool. Using a round seat results in a typical three-legged stool with a round seat. Removing the legs creates a cushion. Suspending a net between two trees creates a hammock.

The listed attributes may be: 1) physical attributes, 2) social attributes, 3) process attributes, 4) psychological attributes, or 5) production attributes.[18]

Follow these steps to extend your thinking beyond some existing product:

- Begin with an existing product, solution, or process. We will use a chair in our example.

- Identify the various attributes of that object that can possibly be modified. These form the column headings of the matrix you will create. For example, a chair has legs that can vary in number, or length. A chair can be rigid, retaining its shape, or can have its shape transformed, by folding for example. Various rests support the weight of the user’s torso, arms, head, or feet. Arm rests can be in various positions. The back can have various geometries. A variety of materials can be used. Various “bonus features” can be added to extend the function of the chair.

- For each column, list several forms or variations that can be imagined for that attribute. Considering chair legs, any number of legs can be used, they can have a variety of lengths or shapes, they can be rocking, swinging, hammock, hang as a pendant, form a pedestal, swivel, or include wheels.

- Choose one entry from each column to describe one style of chair. For example, four long legs, rigid configuration, seat rest, no arm rests, no back, and wooden materials result in a bar stool.

We use a related tool—often called a morphological matrix—when we order a sandwich or a cup of coffee. We specify the type of bread, toasted or not, the filling, and the toppings when we order a sandwich. We specify the size, coffee variety, sweetener, creamer, caffeine level, brewing method, and topping when we order a coffee.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Study the Attribute Matrix Example that describes a variety of attributes for a chair.

- Add any columns that may be missing.

- Add any missing attributes to each column.

- Select one attribute from each column.

- Sketch or describe the chair that is specified by the set of attributes you have chosen.

- Repeat these steps using these examples of ice-cream flavors, or romance novels.

- Create an attribute matrix for a lamp.

- Apply this technique to some real-world problem you wish to solve.

SCAMPER

[edit | edit source]SCAMPER is an acronym that can guide innovators to think of variations of some product with the intent of discovering a useful innovation. It combines brainstorming and varying attributes in a structured search for new ideas.

Each letter in the SCAMPER acronym suggests some transformation or extension of a base product or topic to be explored to suggest some new product. The letters, and their related operations are:

- Substitute comes up with another topic that is equivalent to the present topic. Remove some part of the original and replace it with something different. Constructing vaulting poles from fiberglass rather than ash or bamboo provided safer and higher vaults.

- Combine adds information to the original topic. Join two or more parts together to product something new. Force together two components that are not typically joined. Combining chocolate and peanut butter gave us Reese’s Peanut butter cups.

- Adjust or Adapt identifies ways to construct the topic in a more flexible and adjusted material. Change a component of the original so that it works in some new way.

- Modify, magnify, minify creatively changes the topic or makes a feature, component, or idea bigger or smaller.

- Put to other uses identifies the possible scenarios and situations where this topic or product can be used.

- Eliminate removes ideas or elements from the topic that are not valuable. Bar codes eliminated the need for individual price stickers in the supermarket.

- Reverse or rearrange evolves a new concept from the original concept. Change the order or structure of the original. Reverse cause and effect. Reverse input and output. Reverse start and finish. Reverse predator and prey. Reverse top down and bottom up. Use this list of reversals for other ideas.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose something to improve.

- Identify at least one change that could be made corresponding to each of the SCAMPER transformations described above.

Six Thinking Hats

[edit | edit source]Considering each of the distinct points of view described in the book Six Thinking Hats[19] improves group decision making. Each point-of-view is represented by a distinctly colored hat:

- White — Collect the relevant facts and information.

- Green — Create new options, possibilities, alternatives, and new ideas for the group to consider.

- Yellow — Advocate the present alternative, highlighting the benefits and opportunities.

- Black — Use judgment and critical thinking to examine the present alternative, highlighting the problems, difficulties, and what may go wrong.

- Red — Express feelings, hunches and intuition and share fears, likes, dislikes, loves, and hates.

- Blue — Facilitate the group process by directing attention, discussion, and decision making toward the topics that provide the most insight.

Each of the six thinking hats is a different way of looking at an issue to be considered and decided. Representing a point of view by a hat has the advantage of allowing people to play with a new perspective to get experience with it. They try on the hat and take on a new role. As an example, people who typically argue by criticism can remain mostly critical. But by putting on the red hat they can voice their emotions, or by putting on the yellow hat they can think about positive effects.

During group discussion, each point of view should be considered before coming to a final decision. This can be done in a variety of ways. Members of a newly formed group, or one beginning to use this method, can wear actual colored hats, while each person strictly plays the role defined by their hat. Ensure that each person is heard from, and rotate hats from time to time throughout the meeting. Groups that are more familiar with the idea can simply announce the color of the point of view they are taking or ask to hear from a specific color point of view before reaching a decision. You will know that it is beginning to work when someone speaks up and says: “As I take off my usual black hat and look at this with a yellow hat on, I can see the benefits of this alternative. I think we are getting close to agreeing on an excellent solution. I would like to see some more green-hat thinking, however, before we finally decide.”

Biomimicry

[edit | edit source]Biomimicry pioneer Janine Benyus encourages designers to ask “How would nature solve this problem?” and then observes “Learning about the natural world is one thing, learning from the natural world—that’s the switch. That’s the profound switch.” Biomimicry is the examination of nature, its models, systems, processes, and elements to emulate or take inspiration from in order to solve human problems.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Study the “In Design” section of the Wikiversity course on Natural Inclusion.

- Complete the assignment in that section.

TRIZ

[edit | edit source]TRIZ is "a problem-solving, analysis and forecasting tool derived from the study of patterns of invention in the global patent literature". It was developed by the Soviet inventor and science-fiction author Genrich Altshuller and his colleagues, beginning in 1946. In English the name is typically rendered as "the theory of inventive problem solving"

TRIZ includes a practical methodology, tool sets, a knowledge base, and model-based technology for generating innovative solutions for problem solving. It is useful for problem formulation, system analysis, failure analysis, and patterns of system evolution. There is a general similarity of purposes and methods with the field of pattern language, a cross discipline practice for explicitly describing and sharing holistic patterns of design.

The research has produced three primary findings:

- problems and solutions are repeated across industries and sciences

- patterns of technical evolution are also repeated across industries and sciences

- the innovations used scientific effects outside the field in which they were developed.

TRIZ practitioners apply all these findings to create and to improve products, services, and systems

The TRIZ system is more extensive than can be covered here. Interested students are encouraged to study books on TRIZ, or obtain training elsewhere on the techniques.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Apply your skills in creating possibilities to these example applications. Use divergent thinking skills, tools, and techniques to generate as many possibilities as you can for the chosen example.

Develop—Evaluative Thinking, Making Judgments

[edit | edit source]Development is the application of new ideas to solve practical problems. Here we choose from the many ideas that were identified during the ideation phase, use those ideas to propose a solution approach, and enhance those ideas into a detailed solution description.

The goal of the development phase is to describe a solution. The outcome is a proposed solution or a complete and detailed solution description, design specification, or implementation plan.

Many tools exist that can help us develop nascent ideas. Several are described in the following sections.

Discard the Unsuitable

[edit | edit source]The ideation phase has provided us with an abundance of tentative solutions, solution concepts, or solution approaches. Begin the development phase by discarding any of these ideas that are definitely unsuitable. An idea may be unsuitable for development if it defies the laws of physics, requires changing something you cannot change, or is not morally acceptable.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]Part 1:

- Complete the Wikiversity course on What you can change and what you cannot.

- Discard any candidate ideas that require changing things you cannot change.

Part 2:

- Complete the Wikiversity course on Moral Reasoning.

- Discard any candidate ideas that are not morally acceptable.

Evaluate Suitable Ideas

[edit | edit source]With the unsuitable ideas discarded, turn attention to the remaining ideas. These are all judged as suitable but need to be evaluated to select the most promising from among that various candidate ideas. The following tools and techniques can help to evaluate candidate ideas.

POINT

[edit | edit source]POINT discovers the Plusses, Opportunities, Issues, and New Thinking that can further develop, help us better understand, and evaluate a nascent idea.[20]

When encountering a new idea, focus first on the plusses, the possibilities and opportunities it provides. What does the idea offer? What do you like about it? What new ideas might it lead to? What is the spark of brilliance it reveals?

Now imagine the opportunities it can unlock. What good things might result if this idea was pursued and came to fruition? How might this idea unlock a better future for someone?

Only after carefully and conscientiously identifying the plusses and opportunities do you turn attention to the issues that need to be resolved. Pose each issue as an inquiry into how the problem could be resolved. Rather than “we can’t afford this” ask “How might this be funded?” The Wright Brothers solved the many issues that defeated earlier efforts to attain powered flight by identifying each issue, and then finding a solution. Asking “How can we obtain a powerful lightweight engine to power our craft?” led to a solution. Neither overlooking the issue, nor yielding to despair would have resulted in a solution.

Framing issues as questions can inspire New Thinking and identify new solutions. After many unsuccessful attempts to find an engine manufacture that could meet their requirements, the Wright Brothers turned to their shop mechanic who built a remarkable engine in only six weeks.

Prototyping

[edit | edit source]A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. Useful prototypes might consist of a sketch, engineering drawing, 3D rendering, animation, artist’s rendition, architectural rendering, scale model, mathematical model, simulation, pilot plant, breadboard, elementary or illustrative fabrication, or rudimentary implementation of the proposed product. The prototypes are used to gain experience and feedback from users, researchers, engineers, manufacturers, and others.

Experience gained from exploring each prototype helps to improve the design.

The Wright Brothers used prototyping extensively throughout their development of powered flight. This included:

- Learning from a simple toy helicopter they played with as children,

- Building and flying toy kites,

- Building and flying winged box kites to experiment with wing warping,

- Building and flying gliders to study flight parameters and flight controls,

- Building a wind tunnel and systematically testing many airfoil designs,

- Improving the mathematical flight formula based on their experiments, and

- Learning from each version of aircraft to help design new and improved versions.

As another example, it is reported[21] that Steve Jobs dropped a prototype iPhone into an aquarium. When bubbles rose, he snapped “Those are air bubbles, that means there’s space in there. Make it smaller.”

Foresight Scenarios

[edit | edit source]A foresight scenario[22] is a type of scenario plan used to envision the impact of a new product, policy, or decision. The foresight scenario is a carefully constructed story that describes a future that could unfold if the candidate idea is developed into a final product, service, or policy.

Effective foresight scenarios are plausible, internally and externally consistent, and must aid in decision making.

Foresight scenarios can range from science fiction stories, storyboards, use cases, storm damage forecasts, economic forecasts, sales projections, prototype marketing materials, war games, system simulations, or dystopian or utopian narratives.

The value of a foresight scenario comes from the issues it identifies. Collect these issues from the scenario authors and from those who are asked to review and evaluate it.

Use what is learned from the foresight scenario to choose among alternative ideas, or to refine a nascent design.

Affinity Diagram

[edit | edit source]The affinity diagram is a thinking tool used to organize ideas and data. It is sometimes referred to as the KJ Method. An affinity diagram gathers large amounts of language data originating as ideas, opinions, issues, solutions, etc., and organizes them into groupings based on natural relationships that become apparent and emerge from the data.[23]

The tool is commonly used within project management and allows large numbers of ideas stemming from brainstorming to be sorted into groups, based on their natural relationships, for review and analysis. It is also frequently used in contextual inquiry as a way to organize notes and insights from field interviews. It can also be used for organizing other freeform comments, such as open-ended survey responses, support call logs, or other qualitative data.

In general, an affinity diagram is created using these steps:

- Assemble the Right Team:

- Keep the team small, 4 to 6 people.

- Choose team members who represent varied perspectives.

- Choose creative, open-minded team members.

- Phrase the Issue to be Considered:

- Use a broad, neutral statement. It is often best to be vague.

- State an area of consideration, not a solution.

- Write down the issue for all to see clearly, be sure it is well understood.

- Generate and Record Ideas:

- Do not criticize ideas during this brainstorming.

- It is acceptable to clarify ideas at this point.

- Avoid one-word cards, include a noun and a verb whenever possible.

- Use a separate card for each individual idea.

- Keep ideas visible as recorded on cards.

- Randomly Lay Out Completed Cards:

- On table, wall or Flip chart.

- Sort Cards into Related Groupings:

- Quick Process done in silence (to use the creativity of the right side of the brain).

- Use gut reactions, don't agonize over sorting.

- Move cards to resolve disagreements.

- Allow groupings to emerge, don't pigeonhole cards into standard categories.

- Create Header Cards:

- Look within the group for an appropriate header card (often one will not exist).

- Use concise multi-word headings, discuss with group while composing.

- The header card must make sense while standing alone.

- The header card captures the essential link in all the cards beneath it.

- Place at the top of the group.

- Sub-themes can be turned into sub-headers. Very large groups need to be broken into subgroups.

- Draw the Finished Affinity Diagram:

- Bring together related groupings. The final number of headings should be 5-10 in total.

- Draw lines associating headers with the cards beneath them.

Tree Diagram

[edit | edit source]A tree diagram visually represents the hierarchical nature of some structure. It is useful to assess completeness and relationships of ideas, tasks, components, or other elements of a complex or composite system. A tree diagram can help to create a taxonomy of the topic being studied.

It is often useful to use a tree diagram to further develop and analyze the information that results from creating an affinity diagram. A tree diagram provides an analytical representation that can complement the organic structure of an affinity diagram. A completed tree structure includes terminal nodes or leaf nodes at the lowest level of the hierarchy. These terminal nodes are clearly defined and cannot be usefully subdivided.

The biological phylogenetic tree is an well-studied example of a tree diagram and will be used here to illustrate concepts.

In general, a tree diagram is created using these steps:

- Begin with a statement that clearly and simply states the issue, problem or goal to be explored. The top header statement from the affinity diagram is often a good starting point. It may be helpful to add clarity to that statement before continuing to create the tree diagram. This establishes the top level of the hierarchy that is being created. In the example of the biological phylogenetic tree the top-level organizing statement is “Existing Lifeforms”.

- To create the next lower level of the hierarchy, enumerate all the sub-components of the higher level (parent category). Examine this level of the hierarchy to ensure it is complete, each listed component is distinct from the others, and all are at the same level of abstraction. The “kingdoms” of the phylogenetic tree form the second level of the hierarchy. This level originally included plants and animals and more recently includes bacteria, archaea, and eukaryote.

- Repeat step 2 until the tree reaches a level of detail that clearly defines each terminal node. The levels of the phylogenetic tree known are known as kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. In this example the species are the terminal nodes, however, lower level classifications, such as breeds of dogs, are also defined.

The resulting tree diagram is useful in creating a decision matrix, Quality Function Deployment, action plans, project management, and other thinking tools.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Choose a problem or issue to work on for this assignment. Choose from these example problem topics, or from some real-world problem you are facing.

- Create an affinity diagram that identifies a large number of topics, ideas, sub-problems, related problems, resources, candidate solutions, or issues related to the chosen problem.

- Using this affinity diagram as the starting point, create a tree diagram that organizes the information concerning this problem.

Decision Matrix

[edit | edit source]A decision matrix organizes a systematic comparison of decision alternatives, based on identified decision criteria. It can help developers choose among a variety of proposed alternative solutions and narrow a list of options to a best choice.[24]

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Study this new car decision matrix example.

- Choose some real-life choice you must make by evaluating alternative opportunities.

- Following the new car example, create a decision matrix representing the choice you have decided to study.

- Does the quantitative result from the decision matrix agree with your intuitive decision? Why or why not?

A related tool, called targeting,[25] can be used to move alternatives toward a more ideal solution. Begin by drawing a target, as is used in archery. The bullseye represents the perfect alternative. This imagined alternative attains a perfect score on each of the decision criteria used in the decision matrix. Now use a Post-it note to represent each of the alternatives considered. Place each Post-it note on the target so that its distance from the bullseye reflects the decision matrix score it receives, recognizing only a perfect score would hit the bullseye. Now identify what (low scoring) attributes are keeping an alternative from coming close to that target. Form a challenge statement representing the problem to be solved that could bring that alternative closer. An example challenge statement might be, “how can we improve this alternative so it can move closer to the bullseye?” If the problem represented by the challenge statement can be solved, that alternative can be moved closer to the bullseye.

Quality Function Deployment.

[edit | edit source]Quality function deployment (QFD) is a method developed in Japan beginning in 1966 to help transform the voice of the customer into engineering characteristics for a product. Yoji Akao, the original developer, described QFD as a "method to transform qualitative user demands into quantitative parameters, to deploy the functions forming quality, and to deploy methods for achieving the design quality into subsystems and component parts, and ultimately to specific elements of the manufacturing process.”

The core of QFD is a matrix that links customer needs to technical specifications.

The method is too extensive to describe adequately here. Interested students are encouraged to study books on the topic and obtain specialized training in the method.

Representation

[edit | edit source]As a design emerges, it can be represented in a variety of forms. These may include a sketch, narrative description, technical specifications, engineering drawings, artistic drawings, physical models, breadboard, proof of concept, CAD models, use case scenarios, graphic presentations, video, technology demonstrations, or prototypes.

Implement—Tactical Thinking

[edit | edit source]Implementation is doing. It is the realization of an application, or execution of a plan, idea, model, design, specification, standard, algorithm, or policy. The goal of implementation is tangible results. Implementation translates a strategy or design into tactics and results. It is adopting a solution and putting a solution into practice.

For this course, the outcome of the implementation phases is an action plan. In a broader context the outcome may be tangible results in the real world.

Are we doing this?

[edit | edit source]Implementing an idea can be very expensive. It may be worthwhile to critically review the idea, design approach, or design before committing the considerable resources it will take to implement the project. It may be wise to hold a Murder board to examine the project in depth.

A murder board, also known as a "scrub-down", is a committee of questioners set up to critically review a proposal. The aim of the murder board session is to try to destroy the project rather than to defend it. As a result, at the end of the session the team can be left with all the reasons why this project won’t work. This identifies specific areas where the proposal needs to be improved.

A murder board may be held during or at the completion of the design phase, or at the beginning or anytime during the implementation phase.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Hold a murder board review of the project.

- Adopt the recommendation of the murder board.

Action Planning

[edit | edit source]An action plan is a detailed plan outlining actions needed to reach one or more goals. The goal will be clear from completing the earlier phases described in this course. The solution approach chosen, and design details will also be available as outcomes from the earlier phases.

Begin by identifying all the tasks that need to be completed to progress from the present state (how things are now) to the final state (the goal to be achieved, the problem to be solved.) Use various ideation tools to identify required tasks and events. Group tasks into a tree structure identifying major tasks and related subtasks. Ask “How can this be done?” or “What are some steps that can help get this done?” or “What else needs to be done?” to add detail to high level or poorly defined tasks.[26] Organize these tasks into a time-ordered sequence based on dependencies among tasks. Ask “What do we have to do first?”, What do we do next?”, “What has to happen before we can do this?” to identify interdependencies. Use this time-ordered sequence to establish a more specific timeline. Assign responsibilities for accomplishing each task. Plan to iterate and add detail as the plan is carried out.

The action plan may be represented and maintained as a work breakdown structure that identifies tasks to be completed, subtasks required for each task, resources required, and responsibilities for completing each task.

The Gannt chart is another useful representation of an action plan. It is a type of bar chart that represents the project schedule and may show dependency relationships between activities.

Assisters and Resisters

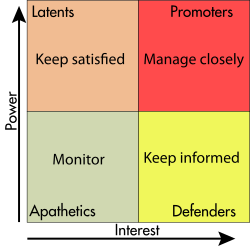

[edit | edit source]Whenever you begin to move forward with some change there will some people who see the benefits of that change, who want to see that change take place, and who may be willing to help make that change happen. There are also others who will oppose the change because they are uncomfortable with change, do not understand the benefits, stand to lose something if the change takes place, or chose to defend the status quo. Those who wish to see the change occur are assisters. Those opposed are the resisters.

It is important to identify assisters, those who can help the project succeed, along with resisters, those who will oppose this project. It is also helpful to estimate the level of influence each person has.

- Begin by using divergent thinking to identify the people and other sources of assistance and resistance the project may encounter.

- For each of the people listed, estimate their level of advocacy for the project, estimated as strongly support, moderately support, indifferent, moderately oppose, or strongly oppose.

- For each of the people listed, estimate the degree of influence they can have on the project, estimated as very powerful, moderately powerful, or slightly powerful.

- Plot each person on the assisters and resisters chart shown on the right.

- Estimate or determine the reasons that cause each person to support or oppose the project.

- For each of the identified assisters, ask “How can we engage these assisters to benefit the project?” Record these action steps.

- For those resisters who you may be able to influence, ask “How can we influence these resisters to reduce their opposition, or perhaps win them over as project supporters?” Record these action steps.

- For each person who you may be able to influence, draw an arrow to the location on the chart to show the position you plan to move them to.

- Include this work in the action plan.

Stakeholder Analysis

[edit | edit source]Stakeholder analysis is the process of assessing a system and potential changes to it as they relate to the relevant and interested parties, known as stakeholders.

A project stakeholder is, "an individual, group, or organization, who may affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome of a project".

Project stakeholders may be inside or outside an organization who:

- sponsor a project, or

- have an interest or a gain upon a successful completion of a project;

- may have a positive or negative influence in the project completion.

Types of stakeholders include:

- Primary stakeholders: those ultimately most affected, either positively or negatively by an organization's actions

- Secondary stakeholders: the "intermediaries," that is, persons or organizations who are indirectly affected by an organization's actions

- Tertiary stakeholders: those who will be impacted the least

Key stakeholders are those with significant influence on or importance within or outside of an organization.

To create a stakeholder map:

- Use ideation techniques to identify a list of stakeholders. Be sure to consider project leaders, project sponsors, senior management, project team participants, users, people who will benefit from the project, people who may oppose the project, people who can help, people who may hinder, subcontractors, consultants, and others.

- Estimate the interest each stakeholder has in this project. Also estimate if they are likely to support, oppose, or be indifferent to the project.[27] Those who can support the project are “assisters”. Those who can oppose the project are “resisters”.[28] Others who may be uninformed, indifferent, or undecided now may change their positions as the project evolves.

- Estimate the power each stakeholder has, and their ability to influence the success of the projects.

- Identify the most powerful assisters and resisters.

- To illustrate the stakeholder map, plot the stakeholders on a “Power-Interest” matrix.

- Work closely with the powerful stakeholders who can help or hinder the project. Monitor, inform, satisfy, influence, and persuade the other stakeholders.

- Include this ongoing work in the action plan.

Project Management

[edit | edit source]Project management is the practice of initiating, planning, executing, controlling, and closing the work of a team to achieve specific goals and meet specific success criteria at the specified time. The primary challenge of project management is to achieve all the project goals within the given constraints of time, budget, and performance, including quality, reliability, and customer satisfaction.

The extent of project management activities needed will depend on the complexity of the project and the size and experience of the project team. Small teams experienced in solving similar problems may be able successfully manage themselves toward a successful project completion. Larger teams, larger challenges, higher risk, more unknowns, and inexperienced team members may require extensive project management efforts.

It is helpful to make progress and problems clearly visible to team members and other stakeholders. Consider maintaining a project dashboard that displays progress, highlights successes and challenges, and provides information that can encourage the team to collaborate to solve problems as they arise.

Navigating, Integrating, Prioritizing

[edit | edit source]Throughout creative problem solving it is important to constantly assess and reassess the situation. This requires deciding what is important to do next, navigating through the complexities of creative problem solving, and establishing priorities.

Important questions must be kept in mind to effectively manage the process. These questions include:

- Is creative problem solving the right approach for addressing the problem we are facing?

- Are we now working to define a problem, describe a solution, create a solution, or gain acceptance for an existing solution?

- What phase of problem solving are we presently in?

- How do we establish the priority of the various problems and opportunities we face?

We can address these questions in order.

Creative problem solving is a useful approach when the problem[29]

- Is your problem to solve,

- Can be solved through imagination, and

- It is a priority for you to solve; it is urgent for you.

If the problem does not meet these three tests, creative problem solving may not be the best approach to use.

The “Creating Possibilities” diagram shown on the right and described in the “Creating Possibilities” course is a map that can be used to help navigate through problem space. The key decisions are:

- Are we working to find, understand, and better define the problem, or

- Are we working to define and describe a solution to a well-stated problem, or

- Are we working to implement, launch, or deploy and existing solution.

These questions help us determine if we should be working in the clarify, ideate, develop, or implement phases.

It is also important to determine if divergent thinking is needed to create new alternatives, or if convergent thinking is needed to choose the best option from among existing alternatives. As illustrated in the “Creating possibilities” diagram, the process alternates between divergent and convergent thinking often as each new phase is entered.

Strategic thinking occurs in the clarify phase. This phase focuses on the questions:

- What do you want to have happen?

- What are the opportunities?

We focus on divergent thinking and generate many candidate alternative solutions in the ideation phase. Creativity is unleased as we pursue fluency, flexibility, originality, and imagination.

Convergent thinking become prevalent as we enter the develop stage. Evaluation, judgments, clarification, and definition are prominent in the Develop state. Here we are working to describe a solution.

With a solution description on hand we are ready to enter the implementation phase. Here we build the product, launch the product, or gain acceptance or adoption of some policy change.

Metacognition—thinking about thinking—is essential throughout creative problem-solving processes to choose the most effective approach to tackle the most important problem or make the next decision.

Success Zones

[edit | edit source]A success zones analysis and map can help the team decide what problems are best to work on based on their importance and likelihood of success.

Follow these steps to create a success zones map:

- Begin with a list of candidate problems to solve, projects to undertake, or solutions to implement.

- Assess the importance of each—the impact they will have if solved—on either a three-point or nine-point scale ranging from low through medium to high.

- Assess the likelihood of success—your estimate of the likelihood of solving this problem—on either a three-point or nine-point scale ranging from low through medium to high.

- Plot each on the Success Zones grid, shown on the right.

- Follow the advice offered by each cell in the Success Zones grid. Drop problems falling in the red zones in favor of those falling in the green zones. Recognize that high importance goals that are unlikely to succeed will require substantial efforts to complete successfully.

- Deploy your efforts as guided by the Success Zones grid.

Unleash Creativity

[edit | edit source]Assess and improve the working environment to unleash the team's creativity.

Assignment

[edit | edit source]- Complete the Wikiversity course on Unleashing Creativity.

- Work to improve the working environment to unleash the creativity of the team.

Summary

[edit | edit source]Many tools are available that can boost your imagination and help with creative problem solving.

Problem solving often proceeds in four phases:

- Clarify—Think strategically to arrive at a precise problem statement.

- Ideate—generate, develop, and communicate new ideas.

- Develop—Choose the best ideas and shape them into a specific solution approach, design specification, or implementation plan.

- Implement—Translate a strategy or design into a detailed action plan or tangible results in the real world.

Throughout creative problem solving it is important to determine if divergent thinking is needed to create new alternatives, or if convergent thinking is needed to choose the best option from among existing alternatives. The process alternates between divergent and convergent thinking often as each new phase is entered.

Use the thinking tools presented in this course when you need a better idea.

Throughout creative problem solving it is important to constantly assess and reassess the situation. This requires deciding what is important to do next, navigating through the complexities of creative problem solving, and establishing priorities.

Recommended Reading

[edit | edit source]Students wanting to learn more about creative thinking tools may be interested in reading the following books:

- Michalko, Michael (June 8, 2006). Thinkertoys: A Handbook of Creative-Thinking Techniques. Ten Speed Press. pp. 416. ISBN 978-1580087735.

- von Oech, Roger (May 5, 2008). A Whack on the Side of the Head: How You Can Be More Creative. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 256. ISBN 978-0446404662.

- Gelb, Michael J. (February 8, 2000). How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day. Dell. pp. 336. ISBN 978-0440508274.

- Covey, Stephen R. (1994). The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. DC Books.

- Jones, Morgan D. (June 30, 1998). The Thinker's Toolkit: 14 Powerful Techniques for Problem Solving. Crown Business. pp. 384. ISBN 978-0812928082.

- Kettler, Todd; Lamb, Kristen N.; Mullet, Dianna R. (December 1, 2018). Developing Creativity in the Classroom. Prufrock Press. pp. 240. ISBN 978-1618218049.

- Gause, Donald C.; Weinberg, Gerald M. (March 1, 1990). Are Your Lights On?: How to Figure Out What the Problem Really Is. Dorset House Publishing Company. pp. 176. ISBN 978-0932633163.

- Stone Zander, Rosamund; Zander, Benjamin (224). The Art of Possibility: Transforming Professional and Personal Life. Penguin. pp. 224. ISBN 978-0142001103.

- Nierenberg, Gerard (1996). The Art of Creative Thinking. Barnes Noble Books. pp. 240. ISBN 978-0760701249.

- Bransford, John D. (February 15, 1993). The Ideal Problem Solver: A Guide to Improving Thinking, Learning, and Creativity. Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-0716722052.

- Plucker, Jonathan (September 1, 2016). Creativity and Innovation: Theory, Research, and Practice. Prufrock Press. pp. 400. ISBN 978-1618215956.

- De Bono, Edward (February 24, 2015). Lateral Thinking: Creativity Step by Step. Harper Colophon. pp. 300. ISBN 978-0060903251.

- Sloane, Paul; MacHale, Des (May 3, 2011). Hall of Fame Lateral Thinking Puzzles: Albatross Soup and Dozens of Other Classics. Puzzlewright. pp. 128. ISBN 978-1402771170.

- De Bono, Edward (August 18, 1999). Six Thinking Hats. pp. 192. ISBN 978-0316178310.

- Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778. http://synecticsworld.com/imagine-that/.

- Pugh, Stuart (February 1, 1991). Total Design: Integrated Methods for Successful Product Engineering. Addison-Wesley. pp. 278. ISBN 978-0201416398.

- Lakoff, George; Johnson, Mark (April 15, 2003). Metaphors We Live By. pp. 242. ISBN 978-0226468013.