Socratic Logic (textbook)

| Subject classification: this is a philosophy resource. |

| Type classification: this is a book resource. |

Socratic Logic is a logic textbook by American philosopher Peter Kreeft, first published in 2004 and then revised and reprinted in 2010.[1] Kreeft perceived a gap in the market, books about logic were either a historical surveys of Socrates, Plato, or Aristotle or primers in symbolic logic.[2]

Approach

[edit | edit source]Why Logic? (Pedagogical motivation)

[edit | edit source]Logic makes your reading and writing clearer, gives you persuasive power, helps you find happiness and gives you the wisdom to find meaning and truth.[3]

Philosophical Starting Points

[edit | edit source]In 1913 Bertrand Russell and Alfred Whitehead wrote Principia Mathematica which became the foundation for Symbolic logic, which in turn laid the foundations for modern coding. Kreeft's purpose, however, is to take an Aristotelian approach to logic, systemizing a coherent approach to logic in the humanities.[4] His starting points are "epistemological realism" which assumes certainty is possible[5] and "metaphysical realism" which assumes that there "universal concepts" that "correspond with reality."[6]

Overview

[edit | edit source]Kreeft provides this overview at the beginning and it forms the foundation for the rest of his work. [7]

| Grammatical Structure | Mental Action | Part of Logic | Individual aspects | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phrases | Concepts | Understanding | Terms | Clear or unclear |

| Sentences | Judgements | Judging | Premises (Propositions) | True or false |

| Paragraphs | Arguments | Reasoning | Arguments | Valid or invalid |

Deductive logical arguments should be contain at least two premises and a conclusion.[8]

- Subject (Term) and verb(Term) = Premise

- Subject and verb = Premise

- Subject and verb = Conclusion.

Understanding

[edit | edit source]Understanding is the first logical act. Terms need to be defined carefully so that they are clear. "A term is the most simple and basic unit of meaning."[9]

Categories

[edit | edit source]Aristotle first formulated the ten traditional categories to describe something.[10]

- Substance

- Quantity

- Quality

- Relation

- Place

- Time

- Posture

- Possession

- Action

- Passion

Definitions

[edit | edit source]| [11] | [12] | [12] | [12] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimalist: What distinguishes it? | Coextensive: not broad or narrow |

Clear, Literal, Brief |

Not negative Or Circular |

| Maximalist: What makes it distinct? |

A nominal (dictionary) definition is part of the search to find an essential definition. Kreeft gives 15 possibilities for "man", "triangle" and "democracy".[13] The clue to finding the essence of something is to find out if a "thing acts as it is ('operatio sequitur esse')."[14]

Predicables

[edit | edit source]"To predicate is to affirm or deny a predicate of a subject."[15] Kreeft goes on to write "Symbolic logic has no room for the predicables because the predicables presuppose the forbidden idea of nature, essence, or whatness. The five predicables are a classification of predicates based on the standard of how close the predicate comes to stating the essence of the subject."[16]

| Predicate | Definition |

|---|---|

| Species | Whole essence |

| Genus | A common aspect |

| Specific difference | Unique only to the essence |

| Property | Flows from, only because of |

| Accident | Sometimes occurs in it |

Tree of Porphry

[edit | edit source]Tree of Porphry, helps you see that the more broadly and simply you define something (extension) the more members your definition will have. In the opposite direction the more specific you are (comprehension), the smaller the group but the more properties you need assign.[17]

Division

[edit | edit source]A form of extension.[18]

- Exclusive

- Exhaustive

Material Fallacies

[edit | edit source]| Material Fallacies[19] |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Judgement

[edit | edit source]

Truth = A direct correspondence with reality.[20]

Propositons

[edit | edit source]Prepositions = "The subject is what is we talking about. The Predicate is what we say about it."[21]

- A universal +

- E universal -

- I particular +

- O particular -

Euler's Circles

[edit | edit source]Calculating the validity of syllogisms.[22] "All (s) is (p)"

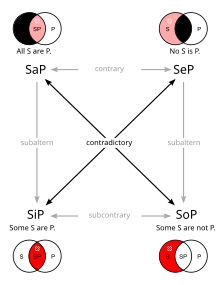

Square of Opposition

[edit | edit source]The square of opposition, finding truth by comparing qualities. [23]

- Contrary A & E = "a universal + & a universal -"

- Subcontrary I & O = "a particular - & a particular -"

- Contradiction A & O, I & E = "a universal + & a particular -" or "a universal - and a particular +"

- Superalternation A and E, I and O = "a universal + and a particular +" or "a particular + and a particular +"

Reasoning

[edit | edit source]How to detect Arguments

[edit | edit source]

"We can evaluate arguments as valid or invalid only after we find them."[24] The presence of an argument is shown by the existence of structure (two or more premises and a conclusion) and keywords (therefore, because, etc). Create an argument map to chart its strategy.

Types of Arguments

[edit | edit source]Three types of arguments:[25]

- Physical relation

- Logical relation

- Psychological relation

Syllogisms

[edit | edit source]- And socrates is a man

- Therefore Socrates is mortal"

"The syllogism is the heart of logic. It is the easiest, most natural, and most convincing form of argument. ... Consider this classic example:" - Identify the conclusion, and major and minor terms (the noun and verb) and then the major and minor premises.[26]

Induction and Causality

[edit | edit source]"Science is not identical with induction. ... Induction, like deduction, is reasoning, and therefore comes under the third act of the mind, not the first; while abstraction comes under the first act of the mind, not the third, yet there is an analogy between the two."[27] Induction is reasoning from the inside, from particular to the universal.[28]

- Causes[29]

- Efficient Causes: the agent that makes, moves or changes (origin)

- Material causes: (contents) the material cause of the sea is water

- Formal causes: the essence (identity)

- Final causes: the purpose (destiny)

We reason from cause to effect and vice versa. We also need to distinguish between necessary (without it, it cannot happen) and sufficient (must happen). Then we must figure out ultimate and proximate causes or remote and immediate causes.[30]

Scientific Method

[edit | edit source]A tool for discovery and thinking.[31]

- Identification of the problem

- Preliminary hypothesis

- Relevance

- Simplicity

- Testability

- Compatibility with known data

- Hypothesis refined

- Process repeated

- power to explain or predict

Formal Fallacies

[edit | edit source]| Formal Fallacies[32] |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bibliography

[edit | edit source]- Kreeft, Peter. Socratic Logic: A Logic Text Using Socratic Method, Platonic Questions and Aristotelian Principles, South Bend, Indiana: St Augustine's Press, 2010.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Socratic Logic (3rd edition)". staugustine.net. St Augustine's Press. 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. x.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 1-7.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 15.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 17.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 27-29.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 30.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 41.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 123.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kreeft 2010, p. 124.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 127-129.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 59.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 56.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 57.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 60.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 145.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 140.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 148-152.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 175.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 190.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 200.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Kreeft 2010, p. 215.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 225.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 313.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 202.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, p. 320.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 325-326.

- ↑ Kreeft 2010, pp. 70.