Motivation and emotion/Book/2011/Achievement motivation

|

| This page is part of the Motivation and emotion book. See also: Guidelines. |

| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

|

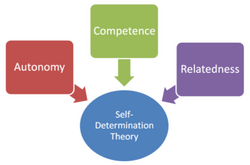

Introduction[edit | edit source]Have you ever wondered how some people go on to achieve great success in a chosen field, yet others seemingly do not have the same sense of achievement motivation? What drives them to excel? Can we influence or promote that same level of achievement in ourselves? This chapter aims to give some insight into achievement motivation, and how we as students, teachers or parents can adopt strategies to encourage an achievement related mindset in ourselves and others, thereby satisfying one of our basic social needs for competence. Sufficed to say, there is no suggestion that changing your behaviours and habits will have you winning basketball games with the personal skill and mastery of Michael Jordan, but improvements to your own personal levels of talent in your chosen field are possible.

Definition and characteristics of high achievers[edit | edit source]So what is achievement motivation? According to theorists, it involves desire for personal competence, competition with a level of excellence, in all likelihood imposed by parents with respect to culture (McClelland, Atkinson, Clark & Lowell, 1975). Indeed Michael Jordan showed extraordinary personal competence and desire in his chosen field of basketball. Rather than be branded merely genetically gifted, and borne out of his rejection from a high school basketball team, his extraordinary achievement motivation saw him labelled one of the hardest working athletes in the sport (Weiten, 2004). Likewise, when beginning his graduate education, B.F. Skinner used disciplined motivation in an attempt to compete with his fellow students (Myers, 2007). That is to say that Skinner scheduled his day to incorporate reading and study around labs, lunch and other daily activities, accounting for all but fifteen minutes in his day to foster his achievements in Psychology (Myers, 2007). Those high in achievement motivation show differences in their choice of task, latency, the amount of effort, persistence and willingness to take personal responsibility for performances when compared to those of low or lower achievement motivation (Atkinson & Birch, 1978; McClelland et al., 1975). Those high in achievement opt for tasks of moderate risk and probability of success, typically prefer feedback on their performance, and are more likely to delay gratification (McClelland, 1985). Whilst theorists have determined differences in these personal orientations, other factors may influence these outcomes. Other influences in achievement motivation[edit | edit source]McClelland et al. (1975) suggested that social and developmental influences, in particular parental child rearing practices, influenced high achievement motivation in children especially when parents adopted high standards. Moreover, children’s continual learning, cognitive development and the pleasure gained from progressive mastery cements personal competence and characterises high need for achievement (nAch) (McClelland, 1985). Motives are said to be based on incentives that are either positively or negatively arousing, thus producing an approach or avoidance of situations that fits into a particular cognitive schema (McClelland, 1985).

|

Does achievement motivation exist and if so, where's the evidence?[edit | edit source] McClelland (1985) purports that tasks of moderate difficulty, competition and entrepreneurship are important in satisfying the need for achievement. Moderately difficult tasks give opportunities for the high achiever to gain more competence. McClelland surmises that as a result of these three situations, high achievers should do well in business as they adopt moderate risk, incorporate high personal performance and seek feedback. The nAch is usually measured by using the "Thematic Apperception Test" (TAT), a projective test that uses pictures of vague scenes. An individual's depiction of those scenes and the subsequent scoring of their answer is then said to reveal the individuals achievement motives (Atkinson & Feather, 1966). By examining the productivity and progress of entire countries, McClelland et al. (1975) have been able to use the TAT to test a society's overall achievement motivation. Atkinson's model (classical view) - and dynamics-of-action model[edit | edit source]This classical view of achievement motivation centres on motives as the central construct. Most notably in Atkinson’s model are the approach motive responsible for achievement motivation and the avoidance motive that encompasses the fear of failure (Atkinson & Birch, 1978; Atkinson & Feather, 1966; McClelland et al., 1975). Atkinson identified that achievement behaviour was dependent on

Atkinson theorised that individuals exhibited a tendency to achieve (Ta), a tendency to approach success (Ts) with a tendency to avoid failure (Taf) (Atkinson & Feather, 1966). The tendency to approach success involved a number of processes including one’s motive for success, the perceived probability and the incentive value of that success (Atkinson & Feather, 1966). Likewise, within the tendency to avoid failure Atkinson believed that the motive to avoid, the perceived probability, and the negative incentive value for failure, all play a part in the overall achievement motivation (Atkinson & Birch, 1978; Atkinson & Feather, 1966; McClelland et al., 1975). In terms of application of this theory, your tendency to obtain good grades will be dependent upon a number of things such as your motive to succeed, and the value you place on it. Conversely, if you don't require good grades (P's make degrees) and there is no motive to succeed, then expectancy and value of success will be decreased (Reeve, 2009). In the dynamics-of-action model, Atkinson and Birch (1978) purport three causes are responsible for ongoing behaviour, namely -

For instance, according to the dynamics-of-action model, you are more likely to exhibit shorter latency and greater persistence in an achievement task if you were interested in that task and were motivated to do it, therefore showing less procrastination. Achievement goals (contemporary view) - mastery/performance[edit | edit source]In this contemporary view, Nicholls (1984) and Dweck (1986) theorised that two main achievement goals exist as the initial construct for this model. Mastery – which is the development of one’s competence, through self improvement, task progress, overcoming obstacles through sustained effort and persistence. With this definition of mastery - one can see the similarities in personal performances exhibited in the earlier example of B.F. Skinner and Michael Jordan. Ames and Archer (1988) identified a positive relationship between mastery goals and intrinsic motivation. Moreover, students that were oriented toward mastery goals reported more effective learning strategies, preference for challenging tasks, overall positive attitude and belief that success was relevant to effort (Ames & Archer, 1988; Klose, 2008). The second goal orientation – performance goals are said to be concerned with one's ability or competence, the desire to display high ability while outperforming others, resulting in success with little apparent effort (Ames & Archer, 1988). Furthermore, when students identify performance as the significant goal, they linked failure to their own ability, hence promoting a non-encouraging self motivation (Ames & Archer, 1988). Whilst both of these goals exhibit performance approach to certain tasks, adopting mastery goals rather than performance goals can produce outcomes whereby the individual will work harder, persist longer and ultimately perform better (intensity, latency, persistence). Individuals adopting a mastery goal are also more likely to ask for information and help, thereby increasing knowledge and understanding (Elliot & Church, 1997; Klose, 2008). Integrated model[edit | edit source]The integrated model is as the name suggests, a merging of the classical approach/avoidance model with the contemporary model of performance/mastery. The result of which sees an achievement goal concept or hierarchical model approach incorporating mastery, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance representations of underlying motive dispositions (Elliot & Church, 1997). Elliot (2006) defines approach motivation as a shifting or focusing of behaviour toward positive stimuli whilst avoidance motivation channels that behaviour by, or away from negative stimuli. The motive identified as being involved in mastery is achievement based, whereas performance avoidance's underlying motive is a fear of failure. Interestingly, Elliot and Church (1997) found that performance approach had both achievement and fear of failure as underlying motives, and this trend was also reflected in competence expectancies. Typically, performance avoidance goals indicated low competence and fear of failure.

Furthermore, performance could also be directed toward a performance-approach or a performance-avoidance position when participants were encouraged to either a positive or negative performance outcome (Rawsthorne & Elliot, 1999). This meta-analysis shows that provided performance outcomes are positive, that is, the belief that one's performance is not fixed, but rather adaptable to change, then performance will increase. | ||||||||||||||

What do those with high achievement motivation practice? So, how do I foster achievement motivation?[edit | edit source]Dweck (1999) posits that personal qualities and characteristics can either be fixed and enduring (entity) or open to change which can be increased with effort (incremental). In effect, individuals are said to adopt goals in achievement motivation that are either entity or incrementally based (Dweck, 1999). Those of the entity belief will usually select performance goals, where fixed personal competence is shown; alternatively, incrementally focused individuals are more mastery focussed and will show changing levels of competence (Dweck, 1999; Howell & Buro, 2008). A study designed to examine the links between implicit theories and procrastination found that entity based beliefs were indeed positively correlated to procrastination (Howell & Buro, 2008). Given the fixed or changing competencies that implicit theory implies, Michael Jordan and B. F. Skinner are more likely to be incrementally focused with regard to their achievement motivation beliefs. Their persistence and intrinsic motivation and belief that they could always improve, shows that personal change is possible with effort. Fostering achievement motivation in the student[edit | edit source]

Student's intrinsic motivation to gain competence and mastery is strong in younger children but changes during ageing to be more extrinsic (Klose, 2008). It seems that self doubt becomes more common place whilst individuals try to place themselves socially. Indeed positive motivational orientation includes an emphasis on personal growth and mastery rather than the negative effects of believing that effort is futile if not compared with others (Klose, 2008). Students with a positive motivation see rewards as feedback for performance on a task, whereas negative motivation see reward and non-reward as feedback on their worth (Klose, 2008).

Klose (2008) proposes that fostering achievement motivation can lead to 'lifelong love of learning'. When mastery goals are adopted within the educational environment, students report their preference for challenging tasks and believe they use more effective learning strategies (Ames & Archer, 1988). Kumar and Jagacinski (2011) propose that increasing task difficulty incrementally in the education environment is seen to have detrimental effects on some individual's perception of competence, especially those using a performance goal approach. They suggest that this decreases a student's perceived ability in their level of achievement. By decreasing the task difficulty, changes in their perceived level of achievement are likely to decrease changes in levels of perceived ability (Kumar & Jagacinski, 2011). Several studies have been carried out to determine whether success in the educational field is based solely on a performance goal approach, or indeed if other intrinsic factors may be present. Predicting success in college study[edit | edit source]

Are GPA's (grade point averages) (a performance goal approach) the only variable worth taking into consideration when determining who will eventually be successful? A study conducted by Harachiewicz, Barron, Tauer and Elliot (2002) examined this question in relation to high school students GPA's, achievement goals and ability to predict college success. Students from a first semester psychology class in a large midwestern university in America were selected for the study and tracked through to graduation. Achievement goals, interest and enjoyment of lectures were measured and final grades recorded and compared to admission grades and data. Findings for this study included the notion that interest (which represented commitment to the psychology field), was a strong predictor of achievement goals rather than ability and prior performance (Harachiewicz, et al., 2002). Having said this, there was a correlation between interest and grades having an influence on longer term academic choices, suggesting that performance goals also influence outcomes. Furthermore, performance-approach goals produced higher GPA's over the initial and overall college course however, mastery goals were found to be instrumental by fostering preliminary and ongoing interest in the course (Harachiewicz, et al., 2002). It is important to note that measurements from this study were conducted in a particular sample, which may not be representative of the general population and hence, could affect overall findings. Nevertheless, high school performance was a positive indicator for ongoing college success, but it didn't indicate interest. This and other findings suggest that modern achievement motivation theorists support a multiple goals perspective (Elliot & Church, 1997; Harachiewicz, et al., 2002) which is not only educationally based, other settings may support this perspective. Fostering achievement motivation in sporting fields[edit | edit source]

Sport is important to us for a number of reasons including the social and developmental aspects and opportunities it affords (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Smith, Smoll & Cumming, 2009). As with educational settings, sport provides similar approach goal patterns of thought, that is that mastery is associated with dedication, effort, intrinsic motivation; ego-oriented individuals on the other hand, link success with superior skill (Smith et al., 2009). Individuals who are mastery oriented report of greater enjoyment of the activity with lower pre event anxiety levels when compared with ego driven individuals (Smith et al., 2009). Whilst ego-driven performance is associated with high achievement, it can produce inconsistent performance and an overall decrease in intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Smith et al., 2009). Motivational climate is referred to as a setting that is conducive to parents, teachers, coaches promoting self-improvement, task mastery, persistence and effort (Klose, 2008; Ames & Archer, 1988) whereas, ego driven climates promote socially comparative settings emphasising winning over improvement (Smith et al., 2009). Sport itself may offer a motivational climate that is more easily recognisable than those in educational settings. For instance, Smith et al., (2009) assert that effort and persistence can be observed through physical signs such as sweating, increase in breathing rate etc. when performing a task. Effort and persistence are not always as easy to detect in the classroom setting (Smith et al., 2009). Empirical evidence identifies coaches as major influencers in promoting mastery in athletes (Smith et al., 2009), therefore, the obvious visual cues produced by athletes may be a useful tool in the coaches arsenal to showcase effort and persistence. With regard to individual wellbeing, athletes higher in mastery report higher levels of fun when compared to those athletes whose coaches promoted winning or ego based activity (Smith et al., 2009).

Summary[edit | edit source]Our desire for personal competence and competition with a standard of excellence is in essence, our achievement motivation. It can be influenced by parents, coaches, educators and/or by adopting strategies that promote mastery and approach goals. It is imperative that the value of effort is promoted - as in incremental over entity theories. Of particular importance is the value we place on environments that adopt positive feedback and endorse individual effort. We can achieve this by -

With sustained effort and persistence, high competence expectancies and intrinsic motivation, individuals will be bringing out their own 'Michael Jordan' or indeed the 'B. F. Skinner' in themselves. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Assess what you have learned[edit | edit source]

|

See also[edit | edit source]

|

External sites

|

References[edit | edit source]Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students' learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), 260-267. Atkinson, J. W., & Birch, D. (1978). Introduction to motivation. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company. Atkinson, J. W., & Feather, N. T. (Eds.). (1966). A theory of achievement motivation. New York: Wiley. Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York: Plenum. Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040-1048. Elliot, A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30. 111-116. doi 10.1007/s11031-006-902807 Elliot, A. J. & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 218-232. Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A meditational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 968-980. Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Predicting success in college: A longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 562-575. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.94.3.562 Howell, A. J., & Buro, K. (2008). Implicit beliefs, achievement goals, and procrastination: A mediational analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 19, 151-154. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.08.006 Klose, L. M. (2008). Understanding and fostering achievement motivation. Principal Leadership, 12-16. Kumar, S., & Jagacinski, C. M. (2011). Confronting task difficulty in ego involvement: change in performace goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 664-682. doi:10.1037/a0023336 McClelland, D. C. (1985). Human motivation. San Francisco: Scott, Foresman. McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R.A., & Lowell, E.L. (1975). The achievement motive. New York: Irvington Publishers Inc. Myers, D. G. (2007). Psychology (8th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91, 328-346. Rawsthorne, L. J., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(4), 326-344. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0304_3 Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding motivation and emotion (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., & Cumming, S. P. (2009). Motivational climate and changes in young athletes' achievement goal orientations. Motivation and Emotion, 33, 173-183. doi 10.1007/211031-009-9126-4 Weiten, W. (2004). Psychology, themes and variations (6th ed.). California: Thomson Wadsworth. External links[edit | edit source]

|