Motivation and emotion/Book/2024/Trauma-informed education

What is trauma-informed education, and how can it benefit students?

Overview

[edit | edit source]Often it’s the most confronting lessons in life that are of the greatest importance. Trauma, however, is pervasive and comes in many forms and often makes learning, being in an educational environment and teaching these lessons difficult for some.

Most people experience some form of trauma in their life and the effect that these experiences can have on people significantly varies and is deeply personal. Trauma-Informed Education is the practice of utilising Trauma-informed care principles within an educational setting to support students who have experienced trauma to minimise negative interactions between traumatic events, the people who experience it and their educational environments.

How do educational organisations ensure that they are teaching often fundamental aspects of life while ensuring the wellbeing of their students? Trauma-informed education is a recent movement to address these concerns, and attempts to ensure that everyone receives an adequate education through the use of effective, evidence based trauma-informed care frameworks.

|

Focus questions:

|

Psychological trauma

[edit | edit source]

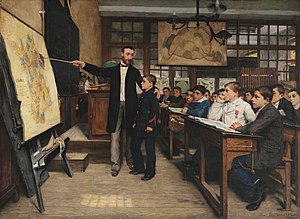

This artwork depicts the history of indifference the education system's material has had on our students. Centre-front of the class, and of particular interest is the distinct, blonde-haired, blue-eyed child, a parody of the "archetypical" German - how would the "German" child react?

Visualised are the potential signs and symptoms of PTSD

Psychological trauma refers to the psychological effects and changes made to an individual following the perception or experiencing of distressing or traumatic stimuli and events eg. violence, abuse, natural disasters. Psychological trauma presents itself through abnormal emotional and behavioural experiences as a consequence of the event. The emotional and behavioural consequences to trauma can persist long after the event has taken place and develop into a disorder. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) categorises these disorders as ”Traumatic and Stressor-Related Disorders”, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD), if the traumatising event has prolonged exposure (Walter et al., 2010). These diagnoses can have significant, abnormal effects on individuals (Figure 2). Other disorders are also significantly linked to psychological trauma and can exacerbate symptoms, such as in Dissociative Identity Disorder (Reyes et al., 2008).

The high prevalence of traumatic events, the varying context they occur and their unique antecedents and consequences reinforce the importance of integrating perceptions of trauma within societal structures. Olff et al. (2020) reinforces that “trauma is the norm rather than the expectation” (p.2).

Types of trauma

[edit | edit source]Trauma is incredibly varied and as such literature has many measures for the features of traumatic events. Spytska (2023) highlights “intensity; significance; importance and relevance; pathogenicity; acuteness of onset (suddenness); duration; recurrence; associations with premorbid personality traits” (p.83), of which each contributes to further varying symptoms and consequences. The cause, context and reason for a traumatic event can influence internal and external reactions and perceptions to the behaviour and emotional responses that distinguish psychological trauma. These types of trauma include natural or human-caused trauma, individual, group and mass traumas, interpersonal traumas, developmental traumas, and adverse childhood experiences (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014).

Prevalence

[edit | edit source]Studies conducted across the world were analysed by Benjet et al. (2016), concluding that on average 70% (n = 125,718) of participants had “reported a traumatic event” and 30% of the participants can recall “four or more” traumatic events (p.2). The prevalence of traumatic events varies across the world on average (figure 1.) and research has shown significantly higher prevalence and effects in demographics associated with poorer Socioeconomic status (SES) (Gluck et al. 2022; MacGregor, 2018).

Trauma in educational settings

[edit | edit source]Research has shown that trauma and related diagnoses can have a significant impact on the development of student’s and ability to learn in educational settings, leaving students to fall through the gaps and at times cause harm (Petrone & Stanton, 2021). These effects have been measured beyond educational settings such as within adult-hood “functioning” and valuable social connections between peers and adults (Jacobson, 2020, p.1).

Children

[edit | edit source]Research supports treating children with trauma as early as possible due to the residual impacts on development and the cumulative effects that occur due to children being the most frequent group to be exposed to trauma while subsequently being the most vulnerable to its negative outcomes and potential to development into psychiatric disorders, of which are theorised to be significantly under-represented or treated (Woodbridge et al., 2016). Academically, children who are exposed to trauma are vulnerable to facing long-term negative effects that influence their educational capacity due to the residual negative effects of trauma (Frieze, 2015), influencing specific and necessary determinants that are necessary for educational success such as creating deficiencies or deviations in learning, behaviour, social, psychological and emotional functioning (Kuban & Steele, 2011) and further cognitive impairments as “executive function, memory, and attention” (Joana et al., 2012, p.758).

Non-attendance to school

[edit | edit source]Literature on “Adverse childhood experiences” (ACE), or trauma within children, represents a considerable factor to the way traumatic events can impact the ability to access school (Stempel et al., 2017) and often culminates in school dropout (Jacobson, 2020). Non-attendance has the ability to reinforce and highlight significant negative health outcomes within absentees, namely associations with “higher levels of chronic diseases, substance abuse, mental health concerns, and early death” (Stempel et al. 2017, p. 837). Trauma is also believed to be a considerable motivating factor towards truancy, which while having the consequences of absenteeism, has further consequences based on the outward perception of the behaviour being an “offence” and thus further stressors through relationships and often the legal system (Hargrave, 2022).

Higher education

[edit | edit source]Trauma doesn’t stop when adult-hood begins and research has noted that the psychological effects of trauma can be a barrier to accessing higher education (Jones & Nanga, 2021). Even when students are able to display competent academic skills to progress students often face difficulties confronting the stress of participating in curriculum especially in demographics who identify within an Intersectionality (p.3). These barriers affect fields that are often deemed necessary to functioning. COVID-19 for example, is a “mass trauma” (see National trauma) that has impacted the wellbeing of nursing students due to the added stress of balancing the detrimental, long term effects of the pandemic and the prerequisites to successfully accomplishing their educational requirements (Goddard et al., 2021).

|

Quiz

|

Trauma-informed education

[edit | edit source]Trauma-informed education is a theoretical framework that attempts to address the high prevalence and significant consequences of trauma throughout the education system, thus improving educational and developmental outcomes for students (Howard, 2018). Trauma-informed education justifies its existence as a remedial and harm-reduction approach to the negative consequences and effects of traumatic events. Howard (2018) speculates that without consideration of trauma within education, organisations themselves as they stand without a framework to address trauma, considering it's prevalence, could actually hinder the recovery process of trauma and reinforce the cost of trauma related consequences.

Recognition of the effects of trauma within education and calls for reform have been well described as early as 1993 (Butler & Carello, 2015) however literature suggests that trauma-informed approaches within education have been limited before 2019 (Maynard et al., 2019). Pressure on educational organisations following COVID-19 led to calls for implementation (Patrone & Stanton, 2021; Harper & Neubauer, 2021) however literature has struggled to highlight a universally effective model based on currently limited research (Avery et al., 2021).

Models and principles

[edit | edit source]There is no universally agreed upon model to implement Trauma-Informed Education (Avery et al., 2021). Current applications of TIE stem from and are based on Trauma-Informed Care models that have been implemented in other, non-educational environments (Sweetman, 2022). (See Trauma-Informed Care). Implementation of TIE varies significantly and different approaches have been tried based on the needs of the specific organisations. The needs of the specific organisations can be perceived through the difference in efficacy and calling for Trauma-Informed Education (p.3)

Trauma-informed positive education

[edit | edit source]Trauma-Informed Positive Education is a model developed on the theoretical framework of positive psychology, and focuses on the teacher’s role in implementing a strength-based approach to minimising and remedying the effects of trauma based on three main principles (Stokes, 2022).

The three main principles of trauma-informed positive education[edit | edit source]

|

Brunzell et al. (2015) in particular explores the necessity of positive education through the consequences of children who experience traumatic events and the corresponding physiological and neurological effects that reside and hinder throughout development, reinforcing that traumatic events can cause "long-term damage to key neurological and psychological systems" (p.64).

Trauma-informed positive education specifically operates under a theoretical assumption that this hindering "long-term damage" expresses itself in children within educational settings through two main factors, dysregulation when confronted with stress and disrupted attachments styles. As such the model highlights two main areas of focus, "Repairing the Dysregulated Stress Response" (p. 66) and "Repairing Disrupted Attachment Styles" (p. 67). Brunzell et al. (2015) further concludes that even beyond the context of children with trauma, studies that implement positive education within mainstream classrooms have "shown to increase levels of student hope... cultivate gratitude, optimism, and life satisfaction... show benefits of mindfulness training... and to promote student learning about signature character strengths and positive emotions" (p.70).

Trauma-informed education within higher-education

[edit | edit source]Higher-education often necessitates reframing confronting materials as a reflection of the world and through broader demographics often reflections of the students themselves. Harrison et al. (2023), for example presents a powerful analysis on the presentation of traumatising materials, reflecting that material is often times reality within the demographics of Australian university students. Harrison et al. (2023) further reinforces that as a consequence of educational organisation's lack of preparedness for teachers to teach confronting material, individual teachers are presented with a dichotomy whereby they either fail to teach the material, or risk "re-traumatisation" (p. 7), "Students notice in Ivan's story, what lives within themselves" (p. 18).

Henshaw (2022) presents trauma-informed education in higher-education as an extension of trauma-informed care, and suggests organisations adopt their core principals "Safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment... peer support and cultural, historical, and gender issues" (p.1) The broader demographics of higher-education necessitates trauma-informed education to adopt principles with extra consideration of culturally appropriate practice through recognition of intersectionality, racial trauma, Critical Race Theory, and respect towards individual Cultural Capital (Henshaw, 2022).

Other principle considerations include (p.5):

- Critical Allyship - The acknowledgement of bias, power and the social relationship educational structures with their students.

- Intentional Positive Disruption - the deconstruction of “normative” (See Normativity) ways of belief.

Davidson (2017) provides a guide to trauma-informed education in higher-education, which recognises that while traumatising materials are often necessary, there is still a role that educators can play in bolstering resilience to traumatic materials, and that while the material may not change, the learning environment can, further highlighting relevant classroom strategies to address traumatic material and de-escalate significant confrontation. Stokes (2022) suggests that for educational changes to adopt trauma-informed practice, there requires foundational policy and curriculum changes to accommodate (p.6-7). Through a number of guidelines, Howard et al. (2022) reinforces theoretical fundamental systemic and organisational changes that are necessary to implement trauma-informed education.

Guidelines for implementing trauma-informed education[edit | edit source]Briefly summarised, Howard et al. (2022, p.6-8) suggests:

{RoundBoxBottom}} Efficacy[edit | edit source]Literature presents a sceptical look at the efficacy of Trauma-Informed Education, suggesting there is a significant lack of evidence that justifies implementing policy changes within educational organisations (Maynard, 2019), and in some particular cases, there is speculation that trauma-informed education could mirror other trauma-based interventions that have been both inappropriately managed, or have gone so far as to cause harm (Ertl & Neuner, 2014), necessitating strong empirical evidence and best-practice. Other research acknowledges the inconsistent results however reinforces theoretical justification for its necessity (Howard, 2018). There is indeed research to support significant improvements in student outcomes such as through improvements in student attendance, expulsion, suspensions (Allison et al., 2019) and in emotional and behavioural measures in students (Roseby et al., 2021) and for teachers, research has shown that embracing Trauma-Informed approaches can reduce stressors and teacher burnout (Kim et al., 2021). Stokes (2022) in particular, however, reinforces that one of the biggest issues in implementing trauma-informed approaches is through he measuring of educational organisation's impact on student learning despite the strong motivation and evidence to support implementing trauma-informed models (p. 3).

Conclusion[edit | edit source]Trauma-informed education offers significant benefit to students through the model's aims at alleviating the corresponding negative effects of trauma presented and reinforced in educational contexts. These outcomes are yet to be fully explored however and the current state of literature remains sceptical towards the approach. The push for trauma-Informed education has had mixed levels of effectiveness in part due to the lack of a “universal” system that has proven efficacy like other trauma-informed care frameworks. Literature has reinforced for a long time that trauma and corresponding “Traumatic and Stressor-Related Disorders” have had significant, negative effects on educational bodies, and that these effects contribute to decreased accessibility, well-being and learning outcomes for students and educators. Calls to address trauma within education have led organisations to adopt Trauma-Informed Care principles and guidelines according to the interpreted needs of the relevant organisations, especially following the significant effects of “mass trauma” such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The distinct application of Trauma-Informed Education within higher-education also further highlights issues to be addressed with the effects of trauma related to disabilities, culture and intersectionality, potentially allowing further application of trauma-informed principles and exploration of issues not commonly addressed by current models of trauma. Despite the lack of efficacy, the approach has significant heuristic and theoretical strength that is reinforced by powerful enthusiasm to integrate the framework by researchers and within organisations, representing the beginning of an accessible and healthy future for our students. See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]Allison, M. A., Attisha, E., Lerner, M., De Pinto, C. D., Beers, N. S., Gibson, E. J., & Weiss-Harrison, A. (2019). The link between school attendance and good health. Pediatrics, 143(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3648

Avery, J. C., Morris, H., Galvin, E., Misso, M., Savaglio, M., & Skouteris, H. (2020). Systematic review of school-wide trauma-informed approaches. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(3), 381-397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1 Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Stein, D. J., Petukhova, M., Hill, E., Alonso, J., Atwoli, L., Bunting, B., Bruffaerts, R., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Huang, Y., Lepine, J. P., Koenen, K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological medicine, 46(2), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981 Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed positive education: Using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemporary School Psychology, 20, 63-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57). Chapter 3, Understanding the impact of trauma. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/ Davidson, S. (2017). Trauma-informed practices for postsecondary education: A guide. Education Northwest, 5, 3-24. Carello, J., & Butler, L. D. (2015). Practicing what we teach: Trauma-informed educational practice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 35(3), 262-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2015.1030059 Frieze, S. (2015). How trauma affects student learning and behaviour. BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education, 7(2), 27-34. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1230675 Gluck, R. L., Hartzell, G. E., Dixon, H. D., Michopoulos, V., Powers, A., Stevens, J. S., Fani, N., Carter, S., Schwartz, A. C., Jovanovic, T., Ressler, K. J., Bradley, B., & Gillespie, C. F. (2021). Trauma exposure and stress-related disorders in a large, urban, predominantly African-American, female sample. Archives of women's mental health, 24(6), 893–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-021-01141-4 Goddard, A., Jones, R. W., Esposito, D., & Janicek, E. (2021). Trauma informed education in nursing: A call for action. Nurse Education Today, 101, 104880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104880 Hargrave, Teri J., (2022). "Impact of Trauma on Truancy" . Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 492. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd/492 Harrison, N., Burke, J., & Clarke, I. (2023). Risky teaching: developing a trauma-informed pedagogy for higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(1), 180-194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1786046 Henshaw, L. A. (2022). Building trauma-informed approaches in higher education. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100368 Howard, J. A. (2018). A Systemic Framework for Trauma-Informed Schooling: Complex but Necessary! Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(5), 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1479323 Howard, J., L’Estrange, L., & Brown, M. (2022). National guidelines for trauma-aware education in Australia. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 826658). Frontiers Media SA. Jacobson, M. R. (2020). An exploratory analysis of the necessity and utility of trauma-informed practices in education. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 65(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2020.1848776 Janice Carello & Lisa D. Butler (2015). Practicing what we teach: Trauma-informed educational practice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 35(3), 262-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2015.1030059 Joana Bücker, Flavio Kapczinski, Robert Post, Keila M. Ceresér, Claudia Szobot, Lakshmi N. Yatham, Natalia S. Kapczinski, Márcia Kauer-Sant'Anna. (2012) Cognitive impairment in school-aged children with early trauma, Comprehensive Psychiatry, Volume 53, Issue 6, Pages 758-764, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.006. Jones, C., & Nangah, Z. (2021). Higher education students: Barriers to engagement; psychological alienation theory, trauma and trust; a systematic review. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 25(2), 62-71. ISSN 1360-3108 Kim, S., Crooks, C. V., Bax, K., & Shokoohi, M. (2021). Impact of trauma-informed training and mindfulness-based social-emotional learning program on teacher attitudes and burnout: A mixed-methods study. School Mental Health, 13(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09406-6 Kuban, C., & Steele, W. (2011). Restoring safety and hope: From victim to survivor. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 20(1), 41-44.ISSN-1089-5701. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ932137 MacGregor, C. (2018). The Context of Trauma: The Interrelation of Trauma, Socioeconomic Status, Family Functioning, and Mental Health Outcomes (Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/177a276e929e9abc8f4312141ea2cbbe/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 Maynard, B. R., Farina, A., Dell, N. A., & Kelly, M. S. (2019). Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15(1-2), e1018. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1018 Olff, M., Bakker, A., Frewen, P., Aakvaag, H., Ajdukovic, D., Brewer, D., ... & Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (GC-TS). (2020). Screening for consequences of trauma–an update on the global collaboration on traumatic stress. European journal of psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1752504. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1752504 Petrone, R., & Stanton, C. R. (2021). From producing to reducing trauma: A call for “trauma-informed” research(ers) to interrogate how schools harm students. Educational Researcher, 50(8), 537-545. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211014850 Reyes, G., Elhai, J. D., & Ford, J. D. (Eds.). (2008). The encyclopedia of psychological trauma (pp. 103-107). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN: 978-0-470-44748-2 Roseby, S., & Gascoigne, M. (2021). A systematic review on the impact of trauma-informed education programs on academic and academic-related functioning for students who have experienced childhood adversity. Traumatology, 27(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000276 Spytska, L. (2023). Psychological trauma and its impact on a person’s life prospects. Scientific Bulletin of Mukachevo State University. Series “Pedagogy and Psychology”, 9(3), 82-90. https://doi.org/10.52534/msu-pp3.2023.82 Stempel, H., Cox-Martin, M., Bronsert, M., Dickinson, L. M., & Allison, M. A. (2017). Chronic School Absenteeism and the Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Academic pediatrics, 17(8), 837–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.013 Stokes, H. (2022). Leading trauma-informed education practice as an instructional model for teaching and learning. Frontiers in Education, 7, 911328. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.911328 Sweetman, N. (2022, July). What is a trauma informed classroom? What are the benefits and challenges involved?. Frontiers in Education, 7, 914448. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.914448 Walter, S., Leissner, N., Jerg-Bretzke, L., Hrabal, V., & Traue, H. C. (2010). Pain and emotional processing in psychological trauma. Psychiatria Danubina, 22(3), 465-470. PMID: 20856194 Woodbridge, M.W., Sumi, W.C., Thornton, S.P. et al. (2016). Screening for Trauma in Early Adolescence: Findings from a Diverse School District. School Mental Health 8, 89–105 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9169-5 |